Technology is changing the world, in good and bad ways. Artificial intelligence, internet connectivity, biological engineering, and climate change are dramatically altering the parameters of human life. What can we say about how this will extend into the future? Will the pace of change level off, or smoothly continue, or hit a singularity in a finite time? In this informal solo episode, I think through what I believe will be some of the major forces shaping how human life will change over the decades to come, exploring the very real possibility that we will experience a dramatic phase transition into a new kind of equilibrium.

Support Mindscape on Patreon.

Here is the 2024 Johns Hopkins Natural Philosophy Forum Distinguished Lecture, given by Geoffrey West:

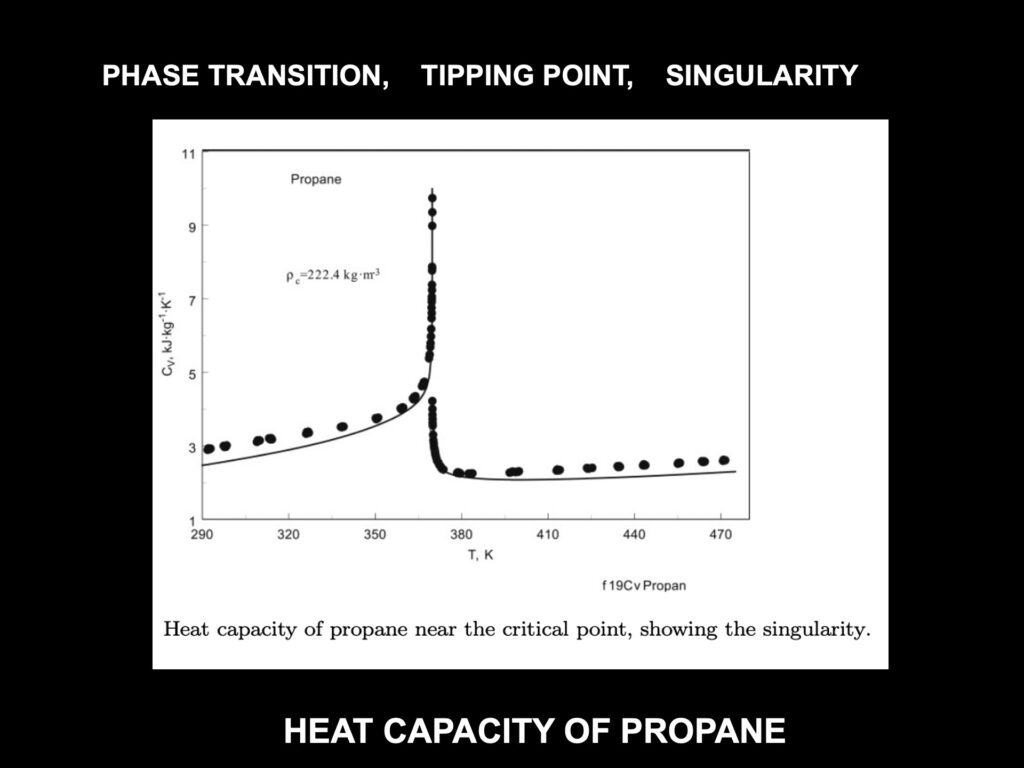

From that lecture, here is a phase-transition singularity, in this case in the heat capacity of propane as a function of temperature:

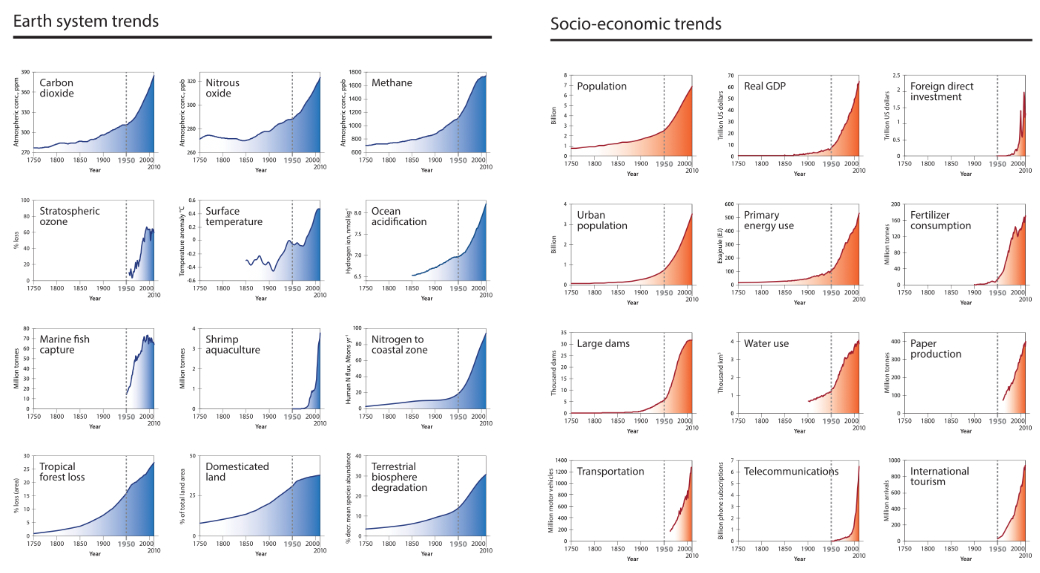

And from the paper "The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration," by Will Steffen et al., here is an image of various trends in Earth-system quantities and socio-economic quantities, where you can see how things are rapidly accelerating in the years 1750-2010.

0:00:00.4 Sean Carroll: Hello, everyone. Welcome to the Mindscape Podcast. I'm your host, Sean Carroll. And as I'm recording this in March of 2024, a few days ago, Vernor Vinge passed away. You might know Vernor Vinge was quite a well-known science fiction author, the author of A Fire Upon the Deep and other novels. Basically, his favorite thing to do was to take technology and to extrapolate it, to imagine technological innovations far beyond what we have in the present day, and then to think about the implications of those technological innovations for humanity, human behavior in society and life and so forth. Yes, something that science fiction has always been very good at. In fact, even if you've never read any of his books, you might be aware of the impact of Vernor Vinge, because he was the one who popularized the idea of the technological singularity. A moment when advances in technology would become so big that a fundamental change would happen in the nature of human existence. He did not coin the term singularity, not quite, not in this sense. It goes back to John von Neumann, of all people. Maybe not surprising, actually, in retrospect.

0:01:08.5 SC: Von Neumann was one of the leading mathematicians and physicists and thinkers of the 20th century. And if you look up the Wikipedia page for the technological singularity, you will find something that I did know, that it was first mentioned in a kind of offhand remark by John von Neumann talking to Oolong. And mentioning that humanity was approaching an essential singularity in technological progress. Now, since then, this idea has been borrowed by others, most famously by Ray Kurzweil. And it has gained a little bit of, well, there's enthusiasm for it in some quarters, there's skepticism about it in other quarters. The specific version of the technological singularity that Vinge and Kurzweil were talking about, we don't know exactly what von Neumann was talking about, but Vinge and then Kurzweil were talking about a technological singularity driven by AI superintelligence. So the basic idea is at some point, artificial intelligence becomes so smart that it will be able to design even smarter artificial intelligences, and then you get a positive feedback loop and runaway growth, and eventually you hit a singularity where the growth is sort of effectively infinitely big.

0:02:28.7 SC: Many people, like I said, have been a little skeptical of this for a couple reasons. Number one, I will mention down the road in this podcast that this might be a slightly overly anthropocentric view of what artificial intelligence is and what kind of intelligence it has. But also number two, because the actual data, the actual evidence in favor of this idea was always a little dodgy. Kurzweil in particular. He was very fond of just plotting things and it was not clear how objective it was what he's plotting, the number of technological breakthroughs over time. Number one, it's not clear why that would matter if it's eventually AI that is going to do the transitioning. Number two, it's not clear how to count what is a technological innovation. Is every new iPhone model a technological innovation? It was just not very well defined and got a lot of hype. People always react against hype. And so it wasn't necessarily taken too seriously in a lot of quarters.

0:03:30.0 SC: Including in this quarter here at Mindscape World International Headquarters. I never really worried too much about the technological singularity. That was not my cup of tea. But recently we had a lecture at Johns Hopkins by Geoffrey West. Geoffrey West, you will all know, he was one of the first guests on Mindscape. I just presume that every listener has listened to every back episode. Geoffrey was formerly the president of the Santa Fe Institute, and he's one of the leading figures in complexity science, a former particle physicist who switched to complexity when the superconducting super collider project was canceled. And Geoffrey has studied scaling laws and networks in biology, but also in human systems. And he wrote a wonderful book called Scale that you can read, or you can read about the scaling law stuff, or you can hear about the scaling law stuff in the podcast episode we did. So this lecture he gave was part of the Natural Philosophy Forum that we now have at Johns Hopkins. And one of the things the Natural Philosophy Forum does is every year a distinguished lecture.

0:04:33.9 SC: So last year it was Daniel Dennett, another former Mindscape guest. This year it was Geoffrey West. And he talked about a lot of his usual stuff, but then he talked about something that I think probably I've heard him talk about before, but it didn't really sink in. You know, this happens. You can hear things, and you can understand them in the moment, and they don't really make an impact on your deeper thoughts until the time is right. And that's what happened with me. The thing he was talking about was essentially the technological singularity. He used that term. He mentioned the history of it, etcetera. But he had much better data than I've ever seen before. He was urging us to take seriously this idea of a technological singularity, but there were two things that, for me, made it much more persuasive than anything I'd heard before. Number one, like I said, he had better data. So he wasn't just plotting how many technological innovations there had been per unit time, but rather the pace at which innovations are adopted. You may have heard that when ChatGPT, the large language model from OpenAI became public, it was adopted faster than any other similar technology in human history, and Geoffrey showed data showing that this is a trend.

0:05:49.6 SC: That not only are we innovating, which we have been for a long time, but it is faster and faster that we are actually, quickly taking up those innovations and adopting them. So that was one thing that I thought was quantitatively a lot more objective and believable than what I had seen before. The other is that he wasn't talking about artificial intelligence that much at all. His story did not rely on any particular understanding of what it means to have artificial intelligence or what it might do. It was just the pace of innovation is increasing for plenty of reasons. The underlying causality is almost irrelevant. His point was that the data are pointing to something like a singularity. And Geoffrey, of course, is a well-trained physicist. He knows the math, and this idea of a curve, you plot something versus time or versus some other variable, and the curve blows up at a finite point. At some moment in time, again, or other variable that is changing with time, the curve seems to go to infinity. So it's of the form one over X as X approaches 0. Right.

0:06:58.0 SC: That is called a singularity in mathematics and physics. And where those things show up in physics, you might think of, in quantum field theory, there are infinities from Feynman diagrams, or in general relativity, there's a singularity at the center of the black hole, and indeed, those are examples of physical quantities becoming infinitely big, but then there's sort of ways to get around them. A much more relevant example is in phase transitions. So a phase transition happens when you have some underlying stuff, water molecules or whatever, and you change some external parameter, density or pressure, or again, whatever, and you measure different physical quantities in this substance as you're changing some overall parameter. And sometimes, well, there can be a phase transition, ice turning into liquid water or whatever, things evaporating. Solids, liquids, gases are the traditional examples, but there are others. And if you measure the right quantity, then at a phase transition, you can find that this quantity goes to infinity.

0:08:02.7 SC: And that's not crazy or ill-behaved, actually. Of course, it never actually reaches infinity because your measurements are not infinitely precise, and there's only literally one point of time or temperature or what have you where that would happen. So the real world always smooths things out a little bit. But the point is that you can still continue the behavior past the singularity in these phase transitions, right? Ice doesn't cease to exist when it melts, etcetera. What Geoffrey actually showed was propane and its heat capacity as a function of temperature. So if you go to the website, my website, preposterousuniverse.com/podcast, I will reproduce that graph that Geoffrey showed for the propane phase transition. Singularities in physically observable quantities are characteristic of phase transitions. So in other words, thinking like a physicist, two things are suggested. And only suggested, not proved or derived or anything like that, but suggested. Number one, we should take the possibility of a singularity very seriously. They happen in real down-to-earth physical systems.

0:09:15.0 SC: And number two, they might be harbingers of phase transitions. It's not that the system ceases to exist or blows up or self-immolates or anything like that. It's just that it changes in a dramatic way to a different kind of thing. You can think of it as there being a sort of equilibrium configuration of the stuff on one side of the phase transition and a different kind of equilibrium configuration on the other side. So, this discussion that Geoffrey had really made me think, like, oh my goodness, maybe this is actually worth taking seriously. That's what we're going to do today. This led me to do this podcast. So, I'd already had the idea of doing the podcast after Geoffrey's talk, before I knew that Vernor Vinge passed away, but it's now even more appropriate. This thing is very hard to think about. What we want to think about is future technological innovations and changes We've talked about such possibilities in the podcast many times in various different modes, but it's hard to be comprehensive.

0:10:15.6 SC: It's hard to put them together, see how different kinds of changes and innovations can affect each other and so forth. It's also both too easy to be extremist. To wildly over extrapolate what's going to happen and lose your sense of accuracy and proportion. And also far too easy to be sanguine to say, you know there's always been alarmists and people saying the sky is falling and it doesn't happen so I can just ignore this. I think we have to be responsible, maybe this is all wrong. Maybe there's no phase transition coming. Maybe the rate of innovation will appropriately slow down or it will continue but we'll handle it in some not very dramatic way. But if you take the numbers seriously, then at some point in the future, 50 or less than 100 years from now, We are in for a shift. We're in for a different way of living here on Earth as human beings. So I'm not an expert on this. I've been doing the podcast for a long time. I've talked to a lot of experts on different things. So this is going to be my untutored, semi-educated reflections and musings on this possibility.

0:11:24.8 SC: Think of it more as an invitation for you to think. Than as anything like a true high credence set of predictions, okay? If you don't believe me, that's 100% fine. I want us all to be contemplating these possibilities. They seem to be important. They seem to be things that we haven't thought about. I'm not going to say we haven't thought about them a lot, because plenty of people have thought about them. I don't think we've thought about them seriously and responsibly enough. So this is an invitation to do exactly that. Let's go.

[music]

0:12:16.9 SC: I thought it would be good to kind of get our bearings by remembering the story of human history, as it were. I am not an expert in this, as you know, but it's important to recall the very basic parts of this story that we probably are all familiar with. At some point in the development of Homo sapiens, we developed language and symbolic thinking, maybe 100,000 years ago, something like that, of that order. The way of sharing information with our fellow Homo sapiens in a way that gave us the ability to do things like cooperate, to build on previous knowledge, to learn and pass down culturally what we have learned. Over the course of time, that led to the innovation of agriculture. We went from a set of hunter-gatherer societies to mostly agricultural ones that opened up possibilities for specialization. Not everyone had to do the same job. And that opened up possibility of social structure for better or for worse. Different people having different roles in the community. Note that people are not necessarily happier in agricultural societies than in primitive agricultural societies than in primitive hunter-gatherer societies.

0:13:32.0 SC: This is something that anthropologists and historians debate about. Arguably, you have more free time in a hunter-gatherer society. Almost certainly, there is more inequality once you go to the agricultural model but maybe you also, on average, have a higher standard of living, maybe a little bit more reliability in your food supply, things like that. But we're not here to judge. That's not the goal. The point is that these agricultural societies with more specialization open the door to different kinds of innovation. And innovation, as a word, is usually attached to scientific or technological, engineering, invention kinds of things, but, there are also innovations in philosophy, in politics, in art, and so forth. And these kinds of things can begin to flower about 10,000 years ago once we invented agriculture. There's a positive feedback loop, as we mentioned before. The population grows because you have more agriculture, more food, and things like that. And then you get more innovation because there are more people.

0:14:40.9 SC: One of the things that Geoffrey West and his collaborators have shown is that, of course, there's more innovation in cities than in rural environments just because there are more people, right? But in fact, the amount of innovation scales super linearly with population density. So in other words, not only do you get more innovation in cities because there are more people, but there's more innovation per person, presumably because the people are interacting with each other, sharing ideas, and things like that. So the rate of innovation speeds up as these transitions begin taking place. But it's also super important to note that the whole thing takes a lot of time. When you're thinking about social structures, innovation, things like that, the space of possibilities, the space of possible inventions or philosophical ideas or whatever, artistic forms, is hugely large. So even if things look like they've been more or less the same for 100 year period, there can actually still be very, very important changes going on. And we see this because, of course, eventually we hit the scientific revolution, industrial revolution, renaissance, enlightenment kind of era.

0:15:58.5 SC: Where things change once again pretty dramatically. So, you know that population has been going up on Earth for a long time. There's details about what it's doing right now, but historically population has been rising since we have had this agricultural shift. But the rate at which population is growing has not been constant. We're all familiar with exponential growth. If there's some time constant over which quantity gets bigger by a certain multiplicative factor, so if you multiply something by two every so often, then you will grow exponentially, and that might look like what population is doing, but the rate of population growth has not been constant. Between the birth of agriculture and the scientific revolution, it grew, but it's been growing much faster. Since the scientific revolution. This is a sign that something is going on more than simply a constant rate of growth.

0:17:00.1 SC: So, hand in hand with the scientific revolution, industrial revolution, etcetera, we get democracy, open societies, cities, all feeding into this culture of innovation. One thing to note, as we're just getting things on the table to remember as we go through this journey, is that it's very, very hard to start with some observation of what is happening and to naively extrapolate. Or rather, sorry, I should have said the opposite of that. It's easy to extrapolate, but it's almost useless. It is incredibly dangerous to extrapolate. We famously have Moore's Law, for example. Moore's Law says that the number of components in a computer chip or the equivalent doubles every, I forget, 18 months, something like that. And that's exponential growth right there. And so exponential growth happens for various kinds of processes. You can extrapolate into the future on the assumption that the exponential growth will continue. Crucially important is that exponential growth never truly continues. There's nothing in nature that grows exponentially forever with the possible exception of the universe itself.

0:18:09.5 SC: Because here on Earth, there is a finite amount of resources that we can use. Or if you think, well, we'll go into space someday, that's fine. Maybe we will. In the observable universe, there is a finite amount of resources. When I did my little chat about immortality at the end of last year, I point out low entropy is a finite resource. And there's no way to just get that to go infinitely. I'm not really talking about these cosmic timescales right here. I'm just pointing out that something can temporarily be exponentially increasing, but have a very different future history. If you look at when we had the COVID pandemic discussion about the rate of growth, and we want to get the rate of growth down low enough that we can handle the pandemic, that rate is calculated assuming that at this instant of time things are growing exponentially. But if you actually look at the number of cases over time, we've all seen these peaks and valleys and so forth.

0:19:09.6 SC: It's a curve, but it is not an exponential growth curve, okay, because many other factors kick in. So extrapolating on the basis of a current rate of growth is always incredibly dangerous. That's not to say growth will always slow down. It could. You might have something that looks very much like exponential growth in some quantity right now, but really it is what is called a logistic curve or a sigmoid It's going to exponentially grow for a while, but it's going to turn over and flatten. In other words, it's extrapolating or interpolating between one almost constant value and a different almost constant value. That kind of behavior can look perfectly exponential. But there's also the possibility of growth that is faster than exponential. So a singularity is mathematically described by, like I said, something like 1 over x. If x equals 0 is in the future, if we're in the minus x regime right now, then that rate of growth is faster than exponential. It's not just constant rate of growth, but the rate of growth itself is increasing.

0:20:14.5 SC: That's another kind of thing that could be happening and it can be very, very difficult to tell just on the basis of some finite piece of noisy data whether you're seeing a sort of pole singularity growth. These are called poles in physics, also in math, or you're seeing exponential growth or something like that. So it's interesting, well it's possibly interesting, it might be completely trivial, but it's interesting to note that when John von Neumann made his offhanded remark about the coming singularity in human development. He used the phrase essential singularity. And he might have just been speaking casually or he might not even been speaking in English. I'm honestly not sure. But he was a very good mathematician and the phrase essential singularity has a precise technical meaning in mathematics. It means the singularity is essential in the sense that it's sort of uncontrollably fast. It is faster than 1 over x or 1 over x squared or anything like that as x goes to zero. An example of a singularity would be an exponential of 1 over x, right?

0:21:26.7 SC: E to the 1 over x grows faster than any power of x. That's an example of an essential singularity. I don't know. One of the things that Geoffrey West points out is that this little offhanded remark by von Neumann was never elaborated upon. We don't really know what he was thinking. It's uncharacteristic of him. He was very careful to write things down and to expand upon them. So Geoffrey says that, in some sense, the work he's doing right now can be thought of as filling in the mathematical details there. But none of that is really super important for the current discussion. What matters is that it is completely possible in these mathematical characterizations of various curves of growth and so forth to apparently reach an infinite value in a finite time. And that is the sign of a singularity or a phase transition or something like that. And I'm going to depart a little bit from what Geoffrey West actually said in his talk. I'm going to link to the talk. If you haven't already seen it, I will link to it at the blog post for the podcast on the podcast web page.

0:22:32.7 SC: Geoffrey's argument is that we can kind of avoid the singularity by continually innovating. That what we need is faster and faster innovation and of course also the ability to deal with those kinds of innovations. And he can see in previous data times when human behavior has shifted in one way or another, from one kind of mathematical extrapolation to a different kind and says, well, we can do that again. And so it's not actually going to be the end of anything when we hit this singularity. So he shows us the plot of propane and the heat capacity of propane going to infinity, going through a phase transition and then finding a new equilibrium, but he's suggesting that that's not actually what will happen. And he does that because you can't extrapolate. What you need is some kind of theory. You need a mechanistic understanding of why these various quantities are growing at whatever rate they're growing at. And he based a lot of his discussion on work by Will Steffen, who coined the term the great acceleration. It's not just one quantity that is growing very fast.

0:23:42.7 SC: Steffen points out that there's a lot of quantities. I'll give a link to that also on the web page. So what Geoffrey is saying is that even though he shows the phase transition plot, he thinks that we're not actually necessarily headed toward that even if we are headed toward a singularity. There's other ways of dealing with it. I don't know about that. I don't claim to understand Geoffrey's underlying mechanistic theory. A lot of it he hasn't published yet, etcetera. So I actually am quite open to the possibility that it is a phase transition. I'm a big believer in phase transitions, by which I mean, the social or political or societal or economic equivalent of The atoms or molecules in a substance having different macroscopic properties. Different emergent properties in the macroscopic realm. Because of slightly different conditions, slightly different overall parameters governing how these microscopic pieces come together.

0:24:45.0 SC: So I think that's very plausibly what we're seeing. We're still human beings. The actual physiology and genetic makeup of human beings hasn't changed that much in the last 10,000 years. It's changed a little bit. It's not going to change that much by natural causes over the next couple hundred years. But we can absolutely interact differently, and it's pretty clear that we're beginning to interact differently than we used to do. So the kind of background idea I have is that if there is going to be a singularity, let's imagine that there is a different kind of equilibrium on the other side. The phase transition singularity that we're approaching will not be the end of the world, necessarily.

0:25:33.1 SC: That's one possibility. I'm not going to really worry about existential risks. And those are real. Nuclear war, biological warfare, pandemics. There's a whole bunch of actually real worries to have, but that's not my intention to think about right here. I'm thinking about, given all these technological changes, can we settle into some quasi-static new mode of living? It might be worse. It might be better. But we should at least think about that possibility. Again, none of this that I'm talking about in this solo podcast is highly rigorous, super research or anything like that. I'm trying to make you think about it. I'm trying to get my own thoughts in a slightly more systematic fashion and inspire you to carry it on from there. So here we go. Again, this thinking about a new equilibrium, the word equilibrium is not accidental. An equilibrium doesn't just mean that you've settled into some particular mode. It means that there is some stability in that mode that you've settled into. Thinking, the word equilibrium started in physics, in thermodynamics. You have thermodynamic equilibrium.

0:26:45.1 SC: Two objects that are at different temperatures, when you bring them together, they will settle down to a common temperature and come to equilibrium. It also appears elsewhere, like in game theory. You have Nash equilibria in game theory, where the different players of the games all have a strategy and they can't individually change those strategies to get better results. They're in equilibrium. So that's the important thing. There's nothing that any individual or any part of the system can do to make things better for themselves, whatever it is meant by better. And I'm revealing a personal opinion that I have here that other people might not disagree with, which roughly translates into saying that values of individuals all by themselves don't matter that much. So, in other words, I'm saying.

0:27:34.9 SC: Encouraging individual people to behave in a certain way is not really going to drive the overall shape of society. If you can, tell people eat less meat or use fewer grocery bags or whatever, these are largely symbolic gestures. If you feel better by doing them, that's great. I do think values can matter, but only when they get implemented as large-scale social constraints. Whether those are literally laws, you can't do this or you get arrested, but maybe the tax policy, certain behaviors, you have to pay more money, maybe it's institutions or whatever. But the way that I think about it, which I think is pretty robust, is that given the large scale constraints, individuals are going to largely pursue their self-interest.

0:28:28.1 SC: Okay. I'm not characterizing what I mean by constraints perfectly because it's not all laws and regulations. You can have broad scale social understandings that are not formally written down, but you need some agreement. You need some consensus. Otherwise, these understandings have no oomph. They're not true constraints. They're just, again, making individuals feel good. As an aside, this makes me very sad that in current discourse between and among people who agree and disagree with each other, you don't see much attempt to persuade other people to your side. Most of the people who I see are just making fun of or disagreeing with people arguing with them. It's hard to make large-scale changes that way. You need everyone to agree, or at least a lot of people to agree, to really agree to change the social system as a whole in a way that would lead us to a better equilibrium. You can't just take the people on your side and fight. You need to actually change the minds of people on other sides, and that's something that doesn't happen a lot these days. And maybe that's part of the technological world in which we live, that certain things are incentivized and certain things are not. Okay.

0:29:46.5 SC: That's the background, that's the throat clearing, telling you what my particular perspective on these things are. So now let's talk about technology and the changes that we are facing. And there are many of them, and I'm not going to go through all of them. Again, super non-systematic here. But let's talk about three aspects, and again, very quickly, superficially. One aspect, the environment. Energy consumption, climate change, things like that. Another one, the sort of biological ways that technology is changing our lives, whether it's synthetic biology or gene editing or whatever. And then finally, computers, artificial intelligence, those kinds of information, electronic technology things that we're also very fond of. I think all of these matter. So this is why it is not just a recapitulation of The Vinge Kurzweil kind of AI superintelligence driven technological singularity.

0:30:42.4 SC: I don't think that's the point, but I think lots of things are happening. So that's the place that I've come to temporarily. Probably I'll change my mind about all these things before too long, but here's where I am right now. So let's think about the environment, sustainability, energy sources, things like that. This is a little different than the other ones because it's more a story of gloom. The environment is something that changes. You know, we shouldn't get into the mindset that there is a right way for the environment or ecology to be, the biosphere for that matter, change is very natural, but we, the human race, are causing changes in a highly non-reflective, non-optimal way. We are making things worse.

0:31:33.5 SC: Change is not the problem. The problem is that we are clearly hurting the environment in very tangible, quantifiable ways. So climate change is clearly getting worse, and it's getting worse faster. You know, that's the recent news is that, people have always said the people who want to deny the reality of climate change have long pointed to the difficulty of modeling the climate. They say, these climate models are not reliable, blah, blah, blah, blah. And I get that. It is very, very difficult. Again, much more difficult than theoretical physics. The climate is a paradigmatic, complex system. There's a lot going on, a lot of different forces at work. But the empirical fact seems to be that if the climate models that we've been trying to work on for the last several decades are wrong, it's wrong because the reality is worse.

0:32:31.7 SC: Than what the model has predicted. Especially in this year, 2024, all the global temperature indicators are higher than we expected them to be. On the other hand, there are small signs of hope. We've talked about these issues on the podcast before. We talked about actual climate change with Michael Mann and the problems there. But we also talked with Hannah Ritchie relatively recently about hopeful prospects. Mostly for cleaning up the environment rather than combating climate change. But Hannah's point was, you can't just become passive and full of doom. You have to keep hope alive. If you have to say, okay, but what can we do?

0:33:17.7 SC: And you have to remember that there is evidence that things can be done, progress can be made. Specifically, when it comes to energy and renewables, we had a podcast quite a while ago with Ramesh Naam, where he talked about the absolutely true fact that progress in renewable energy has been moving faster than we expected it to do. As dependent as we currently are on fossil fuels of all various sorts, there are alternatives that are becoming very realistic and are being implemented. And something that is always true in these discussions of rapid change is that there can be competing influences, both of which are rapid. And there can be a race. So I forget who mentioned this. I always like to try to give credit to people. Someone pointed out to me recently, it might have been Chris Moore at SFI, but we are getting better at things like solar and wind power and things like that, but maybe not so fast that people are ready to wait. Until we are completely converted to those kinds of energy generation. And if they're not, they might say, well, let's build some more infrastructure to burn some more fossil fuels, either natural gas, fracking, whatever it is.

0:34:38.1 SC: And then once that infrastructure is there, we're going to be using it for the next 40 years. So there is a race that is on to see whether or not we can resist the temptation to just burn through more fossil fuels and make the climate even worse. But there's the possibility. Of doing better. There has certainly been a relatively legitimate worry that the only way to cut greenhouse gas emissions would also be to just slow economic growth. There, the evidence is quite optimistic. Namely, in many countries around the world, the rate of economic growth has become decoupled from the rate of greenhouse gas emissions. In other words, there are many countries out there that have been lowering their CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions while nevertheless growing economically. So it can be done. That is a little sliver of hope. It doesn't say we will all choose to do it. It's not necessarily the biggest, the worst perpetrators that are lowering their CO2. And I always like to bring up one of my favorite podcasts that we've ever done was with Joe Walston. Who is a conservation scientist who tries to preserve various species. And he gives a sales pitch and also a sort of prognostication for urbanization as a phase transition. He notes, again, something that the data are pretty clear about, that living in cities is better for the environment than living in, than scattering the human race around urban or suburban places to live.

0:36:12.5 SC: You might visualize cities as having factories and having pollution and things like that, but per person, it is way more energy efficient to have people live in cities. We don't use as much land. We don't use as much fuel to heat your houses because you're living in group buildings and things like that. You don't need to drive as far. So there's many reasons why cities are better for the environment if you have the same number of people. And the good news is the world is urbanizing. So Joe Walston suggests another glimmer of hope that we're entering a new kind of distribution of humanity. Where the vast majority of humans live in cities, there are some who still are out there on the farms living in the country, that's fine. And this is not driven by rules. This is not the communist dictatorship telling you where to live. This is that people are choosing to live in cities at unprecedented rates. And if that comes true, then we can envision at least a future equilibrium where we live sustainably on the land, where we don't ruin. The rainforest for beef or things like that, but we have other ways of getting our food supply and so forth. So I don't, throughout all of this discussion, I have no agenda, really. I'm not trying to convince you one way or the other. I'm exploring the possibilities, and I think one of the future optimistic possibilities comes from urbanization.

0:37:39.5 SC: I think that for a lot of reasons, cities are good if we do them right. But having said that, I think, again, the data are speaking very clearly that at the moment we are destroying the earth. The climate is getting worse. There are positive feedback mechanisms that are making it get worse faster. And the upshot of that is that I don't think it's an existential risk. Existential risks are defined as those that literally speak to the end of humanity as we know it. I don't think it's like that. What I think is that it will lead to enormous suffering as well as enormous economic costs, climate change. So that's bad. I don't think that it's going to lead to the extinction of the human race, but it will absolutely lead to the extinction of other species. It will change the biosphere in very, very important, somewhat unpredictable ways. And it will eliminate much of the land that a lot of people live on now from being livable. It will completely change habits of farming and food production. Guess what? Poor people will be hurt disproportionately compared to rich people. But even the rich people will suffer because it will just cost enormous amounts of money. We will lose enormous amounts of human wealth. We are going to lose enormous amounts of human wealth because of climate change.

0:39:11.6 SC: That's bad it doesn't have to be an existential risk to be bad. And I think we can recognize that it's bad and we should be very, very motivated to do what we can do to prevent it. But there is, like I said, there is still hope for stabilizing things in the future, not even counting like clever scientific possible solutions. Can we terraform our own planet? Can we do things to the atmosphere that will undo the effects of dumping fossil fuels into them in forever. I don't know. I know people get very emotional talking about these things. But I think that medium term, things are going to get noticeably worse for the climate than they are right now.

0:39:55.1 SC: Long term, we will survive, possibly at a different equilibrium. And our job is to make the transition, like give us a soft landing, to make the whole thing as less, as least painful as it possibly can be. So, good. That's all I have to say about the environment and climate change and things like that. Nothing profound. I know that. That's why I wanted to get that out of the way first, because on the one hand, it's super important. On the other hand, you've heard this message before, so there's my version of it. Let's move on to biology, because here's where I think we should, as a society, be paying more attention than we have. To what advances in our knowledge of biology and our technical abilities to manipulate biology are going to do. Going to do for what it means to be a human being. And we've talked a little bit about this set of things on the podcast, but maybe not as much as we could have.

0:41:00.9 SC: So I'll just mention a few things to keep in mind when we ask ourselves these questions. One is longevity. We did have an early podcast with Colleen Murphy, who is one of the world's experts on this, and she has subsequently come out with a book that you can buy on longevity. And I think that there are mixed messages. On the one hand, when you look at little tiny organisms, not just microorganisms, but little tiny worms and things like that, there are remarkable things you can do by playing with the DNA of these little organisms. You can make them live much longer than they ordinarily would. But those particular kinds of changes don't obviously scale up to mammals or other human beings. And it's an interesting situation because there's no rule out there in the laws of nature that says you can't stop or reverse aging. It's an engineering problem, as we theoretical physicists like to say. But it's a very, very hard engineering problem. So, for example, if you track.

0:42:04.9 SC: Average lifespan of civilizations or societies as they become more technologically developed, the average lifespan tends to go up. So you tend to think we're living longer and longer, and that's a trend that will continue. But if you dig into the data a little bit, the maximum lifespan of human beings hasn't actually changed that much. Whether, it's like you think about it as 120 years or something like that. The people who live the longest have been living that long for a long time, regardless of what kind of society they're in. The reason why our average life expectancy is going up is because people aren't dying young nearly as much. We are living, on average, closer and closer to that upper limit. But changes in diet and exercise and medical knowledge haven't really increased the sort of envelope, the cutoff, for how long human beings can live.

0:43:08.7 SC: So in the spirit of taking changes that are going on and imagining that they are indicating that we are heading towards some kind of major transition, I'm going to boldly predict that we are not headed toward a major transition in longevity. As I said, we could at some point do that, but I don't think that we're currently on that trajectory in the medium or short term to do that. I'm hoping that we will live healthier lives and more of us will live to be 100 or whatever, but I don't foresee a lot of people living to be 200 in, let's say, the next 100 years. I could be wrong, of course, very happy to be wrong about that, but I don't think that's where I'm going to bet my money for a major transition. There are other places to put your money for major transitions. One, of course, is gene editing.

0:43:55.8 SC: We did have a discussion of gene editing with Fyodor Urnov, one of the pioneers of this. And there's sort of a hype cycle in these kinds of discussions. When CRISPR first came out, and for that matter, when we first mapped the human genome, people started having panicked discussions. Oh, actually, yeah, we talked to Alta Charo way back, very, very early, discussion in the history of the podcast, we talked about the legal side of bioethics and gene editing. So people had these discussions about, are we worried that people are going to make designer babies and are going to sort of be mucking with our own human genome? And that's going to lead to some dramatic change in everyone is going to be, I don't know, blonde and blue eyed or something like that. Or there will be like all boys and no girls or vice versa? There's a lot of reasons to worry. And some of those worries are just kind of stodgy conservatism. That human race has always been like this, therefore we should not mess with it. I don't buy that kind of at all.

0:45:05.9 SC: You know, I think that if we gather the ability to look into the genetic information inside a zygote or embryo and realize that it's headed towards some terrible disease that we're imagining we have the ability to prevent, then I think we should go ahead and prevent it. But more than that, it doesn't matter what I think. What I think is that it's going to happen. So you can talk all you want about responsible limitations on what scientists can do and what doctors can do, whether or not couples can choose different features of their babies and so forth. I don't think that there's much prospect for any of those hoped for restrictions working. Because we don't have a world government that can make those restrictions, if nothing else. If one country says we're not going to do it, another country is going to do it. And then the first country is going to say, well, wait a minute, they're doing it. We better start doing it also.

0:46:08.7 SC: So I think we have to face up. To the designer babies. I think that they are coming. I don't think that that can be stopped. And it's not just designer babies. I think that this sort of panic over, worrying that people are going to choose a certain kind of child and we'll all become homogeneous and boring, etc, has again led us to not think very carefully and systematically about what the possibilities are. I think we should have more discussion of what the world could be like. And how the world could be good. If when parents decided to have a baby they could also choose its characteristics again I'm not saying that this is what should happen I'm just saying I think it's what will happen I don't think that we have that much choice because the incentive structure does not give me an easy route to imagine that the whole world is going to prevent this.

0:47:10.5 SC: And as Fyodor Urnov said it's not going to be hard you're not going to need a multi-million dollar laboratory to do this you'll be able to do this in your garage. So I think the responsible thing to do is to think carefully about what we want those changes to be like. Like even if we can't stop it, maybe we can stop abuses of it in some effective way. I don't know, but I do think it's going to be a huge deal, and I think we should be talking about it more. A related issue, which I think is going to be a huge deal, is synthetic biology. And we really haven't talked about that very much. It's appeared a couple times in passing. But synthetic biology is not just mucking with the human genome or the genome of a sheep or anything like that, but mostly for tiny microorganisms designing new organisms. Synthetic biology.

0:48:00.2 SC: So going in there and making a genetic code that creates a kind of organism that you want. There's related kinds of biological exploration. Since I'm not a biologist, I just mix them all together in my mind, even though the experts think these are very different. But DNA computers and DNA robots, DNA is obviously very useful to us. It carries our genetic information, et cetera. But there's a reason why that particular molecule is the one that works to carry information in living beings. It's because it's extremely flexible. Forgetting about the actual use of DNA as the carrier of genetic information, DNA is a great way to build things. Microscopic, very tiny-scale objects that do things you want them to do.

0:48:51.2 SC: You can very easily imagine building little DNA robots that will go into a person's body and remove their allergies or prevent them from getting cancer or solve other health problems that could pop up. Synthetic biology could design organisms that could, again, help us with our health problems, but also maybe help eat the carbon dioxide excess that is in the atmosphere, or dramatically change how we do food production, both good old agriculture, making it more effective, but also synthetic meats, other kinds of food sources and things like that. These are going to be huge deals. If you're talking about a technological singularity coming that is going to change human life, I think that editing our genes and synthesizing new kinds of organisms had better be right there near the top of your list. We could imagine, we talked to Lea Goentoro here on the podcast, a Caltech scientist who has in, not human beings, but for much tinier organisms, has regrown limbs.

0:50:02.1 SC: We still are in this world where a lot of people could use these dramatic improvements in our ability to control and shape biological function in ways that we could help them, amputees or people who are suffering in various ways. This is really going to change what it is like to be a human being. I don't think that we will be uploading ourselves into the Matrix. The Matrix movie is going to appear a couple times in this podcast, but I recently read, of course, there was a little panic on Twitter because people realized that their first-year college students, professors, were panicking because their first-year students had not seen the Matrix. They didn't know what it was about. And The Matrix, for people of a certain age, was a very formative movie. And so I encourage you to go see it if you haven't seen it already. But you've heard the basic idea that people are uploaded into this computer simulation, and they think that it's real life. That's the Matrix. So there's both the real physical world, and then there's the Matrix, the simulation they're in, and it's all controlled by evil people and robots and things like that. So it's a fascinating philosophy set of questions, as well as a good movie. For various reasons, that is not the change in human biology that I'm actually thinking about.

0:51:24.0 SC: I'm not worried, or I do not gleefully anticipate that people will upload their consciousnesses into computers. And the reason why is because I know that I'm not a non physicalist about consciousness. I think that you can make conscious creatures out of silicon and chips just as well as you can out of neurons and blood and tissue, but they will be profoundly different. If you take the information that is in your brain and encode it in some computer chip, you have removed its connection to your body. And what we think about as human beings is inextricably intertwined with their bodies. We are embodied cognitions as we have talked about many times on the podcast, Andy Clark, Lisa Aziza Day, and so forth. Our bodies are what make us human just as much as our brains.

0:52:22.4 SC: We get hungry, we get thirsty, we get tired, eventually we die there's all sorts of Antonio Damasio, another person we talked to, he talked about homeostasis and feelings that we have, fundamentally physiological things that profoundly shape who we are mentally. And so it's not that we can't upload the information into a computer, it's just that it wouldn't be a person anymore. It might be something, but it would be different. And that's okay. It's okay for it to be different. So there might very well be creature like things that we recognize as conscious who live in computers, but they won't be the same as human beings. They'll be something different. And that's okay. So I'm not suggesting that that's the big phase transition that we are going to see in the future. But there will be brain computer interfaces, this has been a hot topic lately in the news. Neuralink is Elon Musk's company, but there's actually lots of other companies that are further along in this search for ways to make human brains interface directly with computers. And in fact, that's part of a broader thing, making human bodies interface directly with machines.

0:53:38.4 SC: These are cyborgs or some version of that, depending on how science fictiony you want to sound. This is another technology that I absolutely think is coming and is going to be important. This is going to be a big deal. Think of it this way. Cell phones, smartphones or whatever, even personal computers, whatever you wanna call mobile information technologies connected to the internet. These have already had a very big impact on human life. They've had an impact because poor farmers in Africa can keep track of weather conditions in ways they never could before, 'cause the cell phones are pretty cheap. But also they're changing us socially. There's been enough data by now that I think it's accurate to conclude that cell phones have had a number of negative effects on the lives of young people.

0:54:32.5 SC: And of course, it's not the technology that does, but the uses of the technology, whether it's because they don't go out anymore 'cause they're just texting, or whether they're seeing unrealistic depictions of beauty or whatever. I don't know. And this is something that, it is a conclusion that I was always reluctant to buy into because it sounds a bit alarmist and Luddite, et cetera. But again, I think the data are there. Cell phones have made young people on average less happy than they used to be. And that not a necessary connection, obviously. This is a fixable thing. We are not yet at the equilibrium. We are in a moment of change, of dynamism. We haven't yet figured out how to do these things correctly, how to use these technologies in the best possible way. But my point is, whatever you think the cell phone has done, I think it's easily imaginable that brain computer interfaces are going to be a hundred times more influential than that.

0:55:35.5 SC: If we are embodied. Remember when we talked with Michael Muthukrishnan about various things, but one thing was the fact that human beings tend to offload some of their cognition. Chimpanzees think for themselves more than young human beings do, because human beings have been trained to trust other human beings because we are not just our brains and our bodies. We can write, we can learn, we can teach we can store information and then go access it. So we have not only cell phones, but we have watches and we have calculators and computers and things like that. We have writing and books, all this stuff. Our cognition, our thinking happens in ways that extend beyond our brains and even our bodies. That's gonna explode, to whatever extent we're doing that now, we're gonna do it much, much more in the future for better and for worse.

0:56:38.8 SC: This is not all good, not all bad I am as sort of slightly extrapolating or speculative. I'm trying to be here I'm reluctant to predict exactly what changes those are going to be like. But look, you've all seen quiz shows, jeopardy, who wants to be a millionaire, where you're asking people questions about various trivia questions and things like that, you could imagine that goes away. Because everyone has instant access to the internet. And you can just Wikipedia or Google something right away in your brain without touching anything. And it's much more profound than that, of course you can call up all sorts of pieces of information, not just Wikipedia. You can record things. Maybe rather than a camera in your cell phone you just blink and now you have a recorded image of whatever you're looking at right now, and you can store it and play it back, make videos record conversations. How does this change learning? How does this change performance in all sorts of fields when we have much more immediate access to all sorts of information?

0:57:47.9 SC: Of course there's much more down to earth and obvious impacts of these technologies because again, some people are paraplegic or locked in syndromes of various kinds where brain computer interfaces can help them lead much more rich interactive lives with everyone else. So I'm reluctant to predict what will happen. But again, there's no barrier to these technologies coming and they are coming, there's startups doing them right now, so we should be thinking about, we can't just say, oh, that would be terrible. I don't like it. I wanna live like we've lived for the last 10,000 years. I think we have to take seriously how those technologies are going to change things it's gonna happen whether we like it or not.

0:58:34.6 SC: So I know that leaked into the sort of computer tech kind of thing, but basically that was my biology discussion. I think that there are arguably profound changes in biology that we have so far done not a great job of taking seriously in terms of how they will shape our notion of what it means to be a human being over the next a hundred years. But now, the moment we're all waiting for here, what about AI? Or even more broadly, what about computers and information technology of all sorts. How will that? I think that's just a little bit wrong. I'm sorry. I still think it's a little bit wrong. I said this in my AI solo podcast, and some people, including, by the way, all of the AIs out there, like GPT-4 agreed with me while many other people disagreed with me profoundly when I said that AI, it's crucially important to recognize that artificial intelligences as we currently have them implemented, have a very different way of thinking than human beings do. And what that means is when you toss around ideas like general intelligence, you're kind of being hopelessly anthropomorphic.

1:00:03.9 SC: You're looking at what AI does. If Dan Dennett were here, he would explain that you have fallen victim to an overzealous implementation of the intentional stance. By the intentional stance, he means attributing intentionality and agency to things that behave in a certain way that we are trained to recognize as intentional and a gentle, conscious cognitive thinking. In our everyday experience, we meet human beings and other animals and things like that. And we know the difference between a cat and a rock. And one is thinking and one is not. And so there are characteristics that we associate with thinking well and being intelligent. And it's a rough correlation and it kind of all makes sense to us. And we can argue over the worth of IQ tests or standardized tests or whatever. But roughly speaking, some people seem smarter than others. So when we come across these programs, which are currently the leading ones are large language models, but there's no restriction that that has to be the kind of technology used going forward.

1:01:10.4 SC: The point is, there's a computer that is trained on human texts. It is trained to sound human to the greatest extent it possibly can, and it succeeds. That's the thing that has happened in the last couple years, that these large language model algorithms really, really can sound very, very human. And so, since all of our upbringing has taught us to associate this kind of speech, even if it's just text with intelligence, we go, oh my goodness, these are becoming intelligent. And if it's becoming intelligent and it's a whole new kind of intelligent, then it can become more intelligent than us. And then the worry is that if it's more intelligent than us, it will either be a superhero or a super villain. So our very pressing duty is to guide AI toward becoming a superhero rather than a super villain. And I don't think it's going to be either one, not in the current way that we're doing AI anyway. Again, in principle one could imagine things along those lines, but I don't think that's where we're going right now. So I know that people are worried about artificial super intelligence with the idea that once the computer becomes smarter than us, then we can't control it anymore.

1:02:35.3 SC: 'Cause if we tried to control it, it would resist and it would trick us 'cause it's smarter than we are. What can we do in the face of such overwhelming intelligence? And again, I think this is hopelessly anthropomorphic in the sense that it is attributing not only the ability to sound human to these models, but the kinds of motivations and desires and values that human beings have. The origin of our motivations and desires and values is just completely disconnected from the way that these AI programs work. It is a category error. It is thinking about them incorrectly they might very well develop very, very good reasoning skills of various sorts. After all, my cell phone is much better at multiplication than I am. I do not attribute general intelligence to it. My point is that even if they become better at abstract cognitive tasks, they won't be just like humans except smarter.

1:03:34.7 SC: That's not what they're going to be. So there are different kinds of things, and I think that we have to be clear-eyed about what their effects would be. None of this is to say that the effects will not be enormous. And so I want to emphasize that that's what I'm here to do. I'm not worried about some kind of artificial intelligence becoming a dictator. I'm not worried about Skynet. I'm not worried about existential risks. I'm worried about the real influence that AI is going to have. Not worried, but thinking about the real ways in which real AIs are going to change how we live. I think those changes could be enormously big, even if the way to think about those changes is not as super intelligent agents. I hope that that distinction is a little bit clear.

1:04:27.7 SC: So look, AI is gonna do many things. Many things that are now the job of human beings are going to be done by AIs. It's always amusing to take the current generation of AIs and see them making mistakes. Because they make mistakes. Of course they do. The mistakes they make are mildly amusing. But it's kind of not the point. It's only amusing when they make mistakes because they are clearly super duper good at not making mistakes. That's sounding actually really human. That's much more notable to me than the fact that they still do continue to make mistakes. So things like writing computer programs, writing books, writing articles, designing buildings or inventions or chemistry processes, creating things, creating art, creating life living spaces or whatever, doing architecture. All of these things in my mind is very natural to imagine that AIs are going to play a huge role doing that, either literally doing it or helping human beings do it.

1:05:36.2 SC: Just to mention one very obvious thing, AI will be able to help human beings learn things that they didn't know, not in any sort of simple-minded, let's just replace all professors with AIs or anything like that. But why would you wanna do that? That's not the model you would choose. You personally and individually can learn things with the help of AIs in ways that once we clean up the obvious mistakes that they keep making, which is an ongoing project that might improve very rapidly for all I know, but it will be enormously helpful think about that. I don't know how to, well, again, it's slightly too easy to dwell on the mistakes because there's a thing that's been going around on the internet recently of a cookbook that comes, I don't know, you buy a some oven or something like that, and this cookbook comes along with it and it's clearly AI generated and it's just full of nonsense.

1:06:37.5 SC: And we absolutely need to be worried that some AI produced thing is gonna kill people because it's not actually thinking in the same way we do. And it produces nonsense and someone follows it a little bit too, literally. I'm very much in favor of worrying about that, but it will also more often than not help you learn how to cook or how to speak French, or how to ski or whatever, or how to do theoretical physics. There's no reason to think that AI won't be enormously helpful in that. It'll be enormously helpful in accelerating the rate of other kinds of innovations. So even if the traditional singularity spiel that says AI becomes super smart and it designs other AIs that become even smarter, even if that is not the right way of thinking about it, because the word smart is being misused in that context, the AI will absolutely help accelerate the rate of innovation.

1:07:36.3 SC: When you're a chemist or a biologist or whatever, very often the systems you're thinking about are just so complicated that you have to take some stabs in the dark or some educated guesses and then run trials. Drug trials, this is something that we do all the time. If it's possible to simulate those kinds of trials, you could in principle, enormously speed up the process, all of these things, this discussion we just had about brain computer interfaces genetic engineering, synthetic biology, the rate of progress on those fronts can very possibly be enormously improved. Sped up using help from AI. So that is a kind of bootstrapping positive feedback, acceleration of progress that is characteristic of this kind of singularity behavior. And whether or not you believe in AGI in the traditional sense, there's no reason to be skeptical about that kind of thing.

1:08:38.4 SC: So what is that gonna mean? How will the world be different when AI gets good at these things? Even right now, if you're a basketball fan like I am, and you look up a little recap of last night's games, chances are pretty good that that recap was written by an AI. And sometimes they're terrible. There's still the ability to find real human beings. So most of what I read is by human beings. But the the simple-minded daily story from Associated Press or whatever is often gonna be artificially created so how far is that going to go? So I asked this for my own thought experiment purposes. I wondered, could AI replace me in the sense of writing my books? I've written several books. It maybe could do the podcast too for that matter, but could AI do a good job of writing books in the mode or in the style of Sean Carroll so well that I don't need to write them anymore.

1:09:40.7 SC: That is a crucially important, difficult, interesting very near term question. I think that is not a silly question. I did look. I looked on Amazon, are there any books currently being sold that purport to be by me, but are actually written by AIs? I couldn't find any. I guess that's good. I did find books that are written by AIs that summarize my books. So it's very possible that there are books that are trying to be written by me that just don't attach my name to them. That are sort of a little more subtle than that. But if you search my name on Amazon, you find my books, you find books by former Mindscape guests, Sean B. Carroll, the Biologist, who's written a lot of great books. But you also find books with titles like Summary of the Big Picture. And sometimes these are written by human beings, but sometimes very, very clearly they're written by AIs. And you can tell one way of telling is just click on the Amazon reviews and every review says, ah, this is clearly computer generated and it kind of sucks.

1:10:48.8 SC: But again, the day is young. The progress is still happening. So could you feed a model, a large language model or some improvement thereof, everything I've ever written about and have it write a new book maybe you give it a topic. Maybe you say write a book about I don't know. So Katie Mack, former Mindscape guest, wrote a great book about the ways the universe can end. I've never written a book about that. So you could ask the AI, what would a book by Sean Carroll about the ways the universe could end be like and it could write a book, you could absolutely do it right now, and it would suck. It would not be very, very good at all. But imagine that it gets better.

1:11:37.2 SC: So again, I think that this is going to depend on technologies we don't quite have yet. There is beyond the sort of obvious factual mistakes that AIs are still making right now, there is kind of this difference between interpolation and extrapolation. AIs are good at seeing everything written and kind of going between them. And in things like art this is very, very provocative because you go between two different kinds of art and you get something that is kind of new, but when it comes to sentences, that's less true. If you have different sentences and you're sort of going in between them, which is again, not the only thing AI can do, but a natural strength of large language models, you get sort of something less interesting.

1:12:22.9 SC: Something not as provocative and creative as what you're looking for in a book, extrapolating to say, well here's a sentence, here's a sentence, here's a sentence. The next sentence in a completely different area by the same person should look like this. That's much harder. It's harder to do that in a creative way, given the current ways that large language models and other AIs are constructed because they're constructed to sound as much like they're predicting what comes next usually. And the fun part in a good book is to have what comes next, not be that predictable. So that's a clear tension between what large language models right now are good at and what you want. But I don't think that's a tension that is impossible to resolve. Here's one way to do it. Throw in some random numbers, like imagine that we have enough computing power just write a thousand books and then search through and find the one that is most interesting and creative. That's something you could imagine doing and that could extrapolate in very interesting ways.

1:13:22.4 SC: Now, footnote, I should have said this earlier in the podcast, but one of the challenges back up there when we were talking about the environment, one of the things you might have thought back if you were thinking 20 years ago about climate change and fuel use and so forth, is well, maybe we'll reach a saturation point where we have a constant amount of fuel we need to burn. Maybe once everyone is flying and everyone has their car, we're not gonna need to continue to increase the amount of fossil fuel consumption. Recent years have given a lie to that anticipation, even if anyone had anticipated that, for the simple reason that we continually invent new ways to burn fuel, to use energy, and computing is it right now. Somewhere I read that the, what we call the cloud. When you store your files, your photos or whatever in the cloud.

1:14:30.6 SC: I didn't exactly write this down when I read it, but either the energy consumption or the fossil fuel emission from just keeping the cloud going is larger than that of the entire transportation industry. We're putting an enormous amount of energy into running computers of various sorts. And large language models are some of the worst offenders of this. It's an enormous computational problem, and we would like to do more computation, and that's gonna take more energy. That's a problem. If we think that we are just at the beginning of the AI revolution and other various kinds of ways in which computers are going to be used, just finding the energy to run them is going to be difficult.

1:15:29.8 SC: I just did the thought experiment of imagine writing a thousand versions of a new book by me, and then searching through and looking for the good one that's gonna cost a lot if that becomes common to do. Now there's another problem, which is that at some point you're in Borges's, Library of Babel. Remember Jorge Luis Borges wrote this story, The Library of Babel, which imagined that there's a library that contained every book you could possibly write. And the problem there is you can't find the book. Yes, it's true that War and Peace by Tolstoy is there somewhere, but there's many, many, many, many other books that are exactly like War and Peace, but a few letters are different.

1:16:09.5 SC: So at some point, that's going to be the problem that you face. If you think you can create new knowledge by throwing some random numbers at an AI, finding what the knowledge is versus what the nonsense is, is going to eventually require some judgment of some kind. And so all of which is to say, maybe I can be replaced by AIs writing my books, but there are obstacles to it happening that I don't think make it imminent. I think a much bigger problem than that is the more sort of news social media kind of effects. And here I'm not saying anything at all different than what many other people have said it's already happening. If you go on social media or if you just go on the internet more broadly, it's becoming harder and harder to tell, number one, what was written by a human being versus what was AI generated. Number two, whether images are actually photographs of real things that happened.

1:17:26.0 SC: And this is going to lead to two huge problems. One, of course, is that you can manufacture evidence for whatever claim you like. Oh, you think that this person did this bad thing? Make a video that shows them doing that bad thing. And so it becomes hard to know whether evidence is reliable that way. But the other problem, which I think is underappreciated, is that real evidence becomes less trustworthy. Donald Trump has already used this defense. He says some crazy things. People get him on tape for saying crazy things. And he says, ah, that's just AI generated. You can't believe that I actually said those things. And whether it's true or not, the doubt is there. There is a loss of reliability. There's the loss of the ability to validate the claims that we make in the social sphere. And we've already seen this happening in other ways. But we know what the outcome is. It is kind of an epistemic fracturing. We divide into tribes into bubbles. The problem of a bubble is not that an epistemic bubble and information bubble where, you mostly talking to people you agree with. Who was it? It might have been Brendan Nyhan who talked about this, or Hugo Mercier, I'm not sure.

1:18:50.5 SC: But the problem is not that you're only, I think it was Brendan Nyhan, that you're only exposed to information you want to hear and already agree with. The problem is that you are exposed to contrary information and you just don't pay any attention to it. You just don't listen to it. You don't give it any credence. You don't take it seriously. We human beings, this was Hugo's point, we human beings are really, really good at ignoring the information we want to ignore. And this ability to artificially generate fake information in all sorts of ways is going to tremendously exacerbate that problem. We can plausibly imagine that it becomes hard to trust anything and we descend into a kind of fantastical miasma of entertainment and wish fulfillment or bias fulfillment. So we don't know what to believe, so we believe what we want to believe, and that's it. The reality-based community ceases to exist because everyone chooses to believe or chooses to believe what they want to distrust what they want and maybe rightfully so. If there's just as much crap out there as there is real stuff.

1:19:06.9 SC: So I don't know what the equilibrium will be there. I don't know once it becomes so easy to generate evidence-looking things as it is to generate real evidence. I don't know where we land. I don't know how we change how we evaluate the world, you know. I mean it's already true when we think about politics or international affairs and things like that that we hear claims on the internet that we like and we spread those claims and then someone says actually that was wrong and then it's much harder to bring it back and undo the damage. Again I think we're at the beginning of this change. We're not near the end of it. For whatever various reasons since the internet came to be journalism and newspapers have collapsed, have imploded. It was actually as many of you know if you want to point a finger at one event that led to the collapse of journalism it was Craigslist. Craigslist the online classified service because many many newspapers actually got most of their revenue from their classified sections and again going back up to the discussion of people are going to follow their self-interest if they're allowed to do so it is better to have classifieds online and widely available to everyone than to have them individually printed in physical newspapers.

1:21:39.2 SC: It's just easier. So the model of newspapers and their revenue streams sort of went away and you can plot that very dramatic transition pretty easily and this is a new thing, the shift to distrusting pieces of information is a different kind of thing but it'll be equally important if we don't have things that we can rely on. So that's going to be a big deal. Okay, so given all that. So again all of this is sort of slightly meandering exploration of what I think are technologies that will really lead to huge important changes. What do we think is going to be the end story? If it's true that we're approaching a singular moment after which human life and society will look different, what will it look like? And I'm gonna be brutally honest here, I'm gonna disappoint you if you want to get the answer, the correct answer from me 'cause I don't know. I think it's a very hard question to ask. I think it's very worthwhile to ask. I think that I guess I've said this already but when people talk about it I just don't think they're being serious in the sense that they are too not eager but susceptible to either wildly over exaggerating effects or under appreciating the possible effects.

1:23:10.0 SC: I think that the balance, and I don't blame people. I'm a person, it's very, very hard to strike the balance, between carefully thinking through all of the possible things that can happen, And yet sort of soberly imagining which ones are more likely than others. So that's what I'm trying to encourage people to do. I'm not successfully completing that program, but I hope that, I can give some food for thought for people who wanna think it through. So, to acknowledge that I don't know what the answer is, I will sketch out two sort of edge case scenarios, a pessimistic scenario and an optimistic scenario. And, originally I thought of doing the optimistic one first and then the, warning of the pessimistic scenario. But that's depressing. So, let me do the pessimistic one first and close with the optimistic one, even though you'll have to judge for yourself, which you think is more plausible given the things that are happening to us. So the pessimistic scenario, a good analogy, a good metaphor once again, comes from the Matrix, the movie, but not from what most people take to be the central theme of the matrix.

1:24:24.2 SC: The possibility that we're living in a computer simulation or something like that. Many people, and myself included, have pointed to one aspect of the Matrix movie as the silliest, and the one that we really wish had not been part of it. And that is the following. Of course, there is still in the world of the Matrix, a physical world. So people have physical bodies, but their experiences, their thoughts, et cetera, are all in the matrix. They're all in the simulation. So what are most, and you know, our plucky heroes, our, you know, pirate rebels who are navigating the real physical space, but most people who are living their lives in the matrix, what are their physical bodies doing? And in the world of the movie, they are batteries. Basically. The technology of the computer simulation is powered by human bodies. So all the human bodies are put in these pods and hooked up to tubes and wires and whatever. It makes for great visuals in the movie, but completely hilariously nonsensical in terms of thermodynamics and physics.

1:25:34.4 SC: Human bodies don't create energy. They use up energy. It's the opposite of what you would want. We're terrible batteries or power generating sources or whatever you might want to be. So I and others have made fun of the matrix movies for that particular conceit. But finally, I don't know, I honestly don't know whether this is in the intention of the Wachowskis when they made the movie, or whether, it's just a good way of thinking about it. Finally, it occurred to me there's a much better way of thinking about that image of the people powering the matrix, which is to not take it literally, but to take it metaphorically. In other words, to imagine that what is being imagined is not that our literal ergs and jewels that we human beings create are powering the matrix, but that our human capacities are powering this particular fake reality.