Erwin Schrödinger’s famous book What Is Life? highlighted the connections between physics, and thermodynamics in particular, and the nature of living beings. But the exact connections between living organisms and the flow of heat and entropy remains a topic of ongoing research. Jeremy England is a leader in this field, deriving connections between thermodynamic relations and the processes of life. He is also an ordained rabbi who finds resonances between modern science and passages in the Hebrew Bible. We talk about it all, from entropy fluctuation theorems to how scientists should approach religion.

Support Mindscape on Patreon.

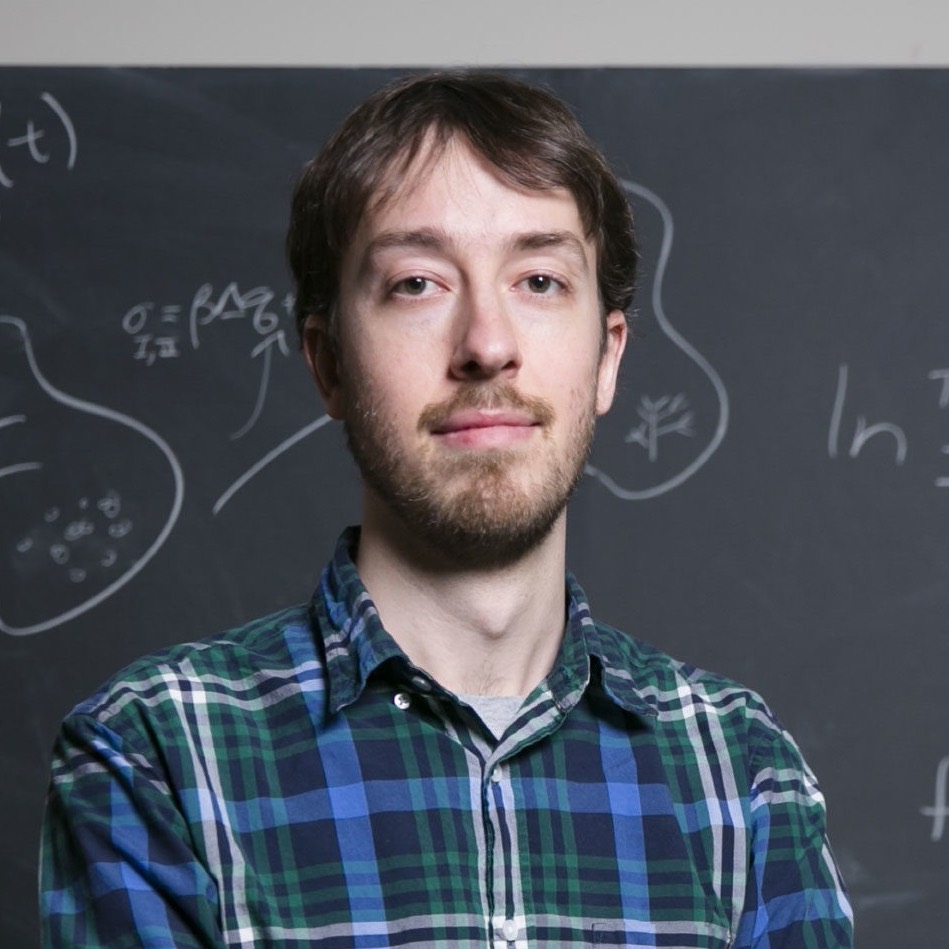

Jeremy England received his Ph.D. in physics from Stanford University. He is currently Senior Director in the Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning group at GlaxoSmithKline. He has been a Rhodes scholar, a Hertz fellow, and was named one of Forbes‘s “30 Under 30 Rising Stars of Science.” His new book is Every Life is on Fire: How Thermodynamics Explains the Origins of Living Things.

- Web site

- Google Scholar publications

- Talk on Non-Equilibrium Statistical Mechanics and Life

- Amazon author page

- Wikipedia

[accordion clicktoclose=”true”][accordion-item tag=”p” state=closed title=”Click to Show Episode Transcript”]Click above to close.

0:00:00 Sean Carroll: Hello everyone and welcome to The Mindscape Podcast. I’m your host, Sean Carroll. Long-time listeners will know that there are two things I’m really interested in, one is entropy. I mean, there’s more than two things I’d like to think but anyway, two of them. Entropy, the arrow of time, right? How entropy increases over time is the language of statistical mechanics and why that draws a distinction between the past and the future and then separately but in a related sense, life. The idea of biological life, the origin of life, the evolution of life. So it’s very natural and we’ve done it before to bring these two things together because living systems are physical systems. They obey the laws of physics and so it’s…

0:00:40 SC: They’re out of equilibrium systems, they’re systems that are open and interact with their environment and they take part in, they participate in the overall increase of entropy in the universe. So today’s guest is one of the world’s leaders in thinking about this intersection of statistical mechanics and entropy with life, both it’s origin and it’s evolution and it’s functioning on a day-to-day basis.

0:01:02 SC: Jeremy England is well known, especially to readers of Quanta Magazine. Quanta which is one of my favorite science magazines has profiled Jeremy talked about his work a lot. What he’s doing is taking modern advances in non-equilibrium statistical mechanics; that is to say not just the simple fact that entropy increases but the ways in which it increases and the fluctuations around the overall tendency to increase and applies them to what life is, how it operates, how it originated but there’s a twist to this story.

0:01:34 SC: I mean, Jeremy would be a very obvious mindscape guest but the twist is the following, Jeremy is also an ordained Rabbi in the Orthodox Jewish tradition and in his new book called Every Life is On Fire, How Thermodynamics Explains the Origins of Living Things, Jeremy does not shy away from talking about the relationship in his mind between his Jewish faith and the words that he reads in the Hebrew Bible and his ideas about physics and biology. So I thought this would be a fun thing to talk about, obviously a very different perspective than what I usually have. It’s just a fun and weird conversation ’cause when we’re talking about physics and biology, were very, very much on the same wave length more than most physicists or biologists but then he was really into reading the Bible in a way that I’m really not into that.

0:02:24 SC: So it’s a very nice way to learn from someone who is a very smart person thinking about things in a very different way. So you may agree or disagree with any part of the podcast but I hope that it gives you something to think about. That’s why we’re here. So let’s go.

[music]

0:02:57 SC: Jeremy England, welcome to The Mindscape podcast.

0:02:58 Jeremy England: Thank you very much.

0:03:00 SC: So we share a weird kind of quasi-notoriety. I was slightly perplexed and I guess tickled but also weirded out to see the name of my book, the big picture, appear in Dan Brown’s novel called Origin but then you did way better than I did, ’cause you’re a character in that book.

0:03:24 JE: Indeed. Indeed yes.

0:03:26 SC: Not because of anything that you had anything to do with. [chuckle]

0:03:26 JE: That was a surprising moment for me. I guess, was it… It was three years ago and a few months that I found out it was happening and then the book came out, I think almost exactly three years ago and that was a peculiar time. An unexpected one too.

0:03:44 SC: You had no idea, right? He didn’t talk to you and you were not even…

0:03:46 JE: Yeah, no. He asked me to have lunch with him a month before the book came out and I didn’t know why. I speculated maybe he was starting to write a book and he was talking to scientists to try to get ideas and he told me the book was about to come out and I said “Oh, that’s interesting.” and so that was one of the more surprising things that happened to me so far in my scientific career.

0:04:15 SC: Well look, in some sense, it’s not surprising. You’re thinking about ideas that bring in together notions from physics and biology and the origin and nature of life. Big picture kind of ideas and it’s kind of catnip for a novelist who wants to juice up their story with some profound consequences but you weren’t happy with how you were portrayed as I recall.

0:04:39 JE: Yeah well, I think that it’s not an irrelevant subject for the discussion of my own book that we’re having now because while on the one hand, obviously the research that I was doing before ever having any involvement in fictional pieces written by Dan Brown was something I already was interested in and motivated to pursue and excited by and while also thinking about broader questions about what other languages there are with which we can talk about the boundary between life and non-life and how the human experience as a whole is impacted by how we view life and think about what it is.

0:05:25 JE: Well I was also already quite interested in that. I think I didn’t really have the same kind of fire lit under me to try to combine both discussions in one book until Dan Brown helped me to become so aware of how much potential for public reaction beyond the scope of the science there is when you start putting ideas like this out there and I think especially being portrayed as someone who wasn’t interested in the broader discussion really made me feel like “No, I really am interested in the broader discussion so maybe I should just make sure to go on record at length to that effect.”

0:06:01 SC: Yeah, that’s actually a really good point. I hadn’t thought about it in those terms but you’re right because I know that when I give talks on cosmology I learned this from Martin Rees, a world famous theoretical astrophysicist, he gave a popular level talk on cosmology and in the middle of it, he started talking about life on other planets and I’m sitting there in the audience as a cosmologists, I’m thinking “Wait a minute, that’s not cosmology. Why are you talking about that kind of stuff?” But we forget that the people out there who are interested in these things don’t draw the these strict boundaries in the same way that we do and it’s actually useful to try to step outside and make these connections that we’re not supposed to be making in our professional lives.

0:06:41 JE: Yeah and I think especially the question of how life might have might’ve come into being, when we talked about in the language of physics or looking at the universe in a forensic way and trying to cast a glance backward. Once you’re engaging in that discussion, I think there’s no question that there are people who line up along either side of what they view as a line of scrimmage between the natural sciences and biblical religion and they’re looking for a winner-take-all outcome and so I didn’t wanna pretend to be naive and say “Oh, well, I’m just sharing some thoughts for people’s delightation.”

0:07:24 JE: ‘Cause I think it’s too clear that if you come out and say “Okay, I think we understand something more about where life-like behavior comes from in physical terms.” there are people who are going to… And really, who already have take that and say “This is the last stake in the heart of believing anything the Bible has to say.” And at the end of the day, I am coming from a personal place as well. In adulthood, after kind of growing up as a theoretical physicist, I decided that being a Jew was important enough to me to invest a lot more effort in studying the Torah and the rest of the Hebrew bible and my tradition and I’ve been quite gratified at the intellectual depth that I find there in engagement with these questions.

0:08:11 JE: So I don’t myself see the contradictions or the throwdown winner take all kind of fight that I referred to there. I don’t see it as being necessary but I’m conscious of how readily that pops up and I do think it’s an important additional discussion to attach to this just to make sure I’m not putting stuff out there that will get essentially used to push in a direction that I myself am not particularly interested in pushing.

0:08:43 SC: Yeah and I think that it’s a very important discussion. We’ll definitely get there but even before getting there, there’s a whole nother another line of scrimmage, which is between biology and physics, right? Even before you bring in the third corner of the hat. So why don’t we start there to lay some ground work and on the podcast, we’ve talked about these things before. We’ve talked about the origin of life and things like that but everyone has a slightly different take on this. Why don’t you tell me what you have in mind when you talk about the origin, the nature, the process that we call life.

0:09:16 JE: Sure so I think that this is something I try to treat somewhat carefully in the book. I think that when starting this discussion, the most important first thing is to realize that you can be talking about the world as a scientist and actually there are different languages you could choose to use and I think we sometimes miss that ’cause we think of science as this monolith and we just sort of wanna say “What does science say about this?” But within science, just the difference between looking at the world as a physicist or looking at the world as a biologist, you have different categories and different vocabularies and different criteria that you take for granted in how you make sense of the same phenomenon.

0:10:00 JE: So I could talk about the world as a physicist and then if I’m gonna do that, I’m gonna start by trying to be very basic and say “Let me say what numbers can I get out of making certain basic measurements? I can measure distance, I can measure time, I can quantify an amount of substance, etcetera.” And then you build up this whole framework for how do I predict these numbers from those numbers and it’s an inherently quantitative enterprise.

0:10:23 JE: Biology by contrast, I would argue, is not inherently quantitative in the same way. In present day biology, there’s a huge amount of quantification that goes on and it’s very useful for addressing certain kinds of questions but if you go back to the beginning, the idea of what is alive is something taken for granted at the outset of biology. You say there’s this group of things in the world that are alive, like clams and people and trees, etcetera so now let’s try to make a science out of what keeps them alive or stops them from being alive and that can be begun at least in qualitative terms.

0:10:56 JE: You can find out that when you cut off a chicken’s head, it always dies and there’s not really a numerical analysis that needs to be done there in order for that to become very good empirical science and that’s, I think, fundamentally different from physics. You can’t get physics going without starting to talk about the world in terms of numbers that you make out of it and by the way, in terms of numbers that our priority don’t see the difference between life and non-life. You could look at a table or you look at a frog and if you’re being really fundamental in your physical description, you just say “Well, in both cases, I have a bunch of molecules or I have a bunch of particles, atoms. I have a bunch of quantum fields.

0:11:34 JE: However, whatever frame you’re putting on it, the difference between those two objects is a sort of a different initial condition or a different assembly state of similar materials and it’s not something where the physics draws a bright line for you in a qualitative sense. So just the fact that you come to the world in the same phenomenon in the world and say “Okay, if I toss a cat off a tower… ” because physicists always like endangering cats in their thought experiments.

0:12:01 JE: “If I toss a cat off a tower, I can ask how fast is it moving when it hits ground and that’s a physical question or I could ask whether it’s alive afterwards and that’s a biological question and even if there’s some translation I can make between these two conceptual frames, it’s never gonna be the same thing to ask if something is alive as it is to ask how fast it’s moving and we need to recognize our own role in engaging in that work of translation.

0:12:26 SC: Well, you’re suggesting or you’re hinting at a whole bunch of discussions people have had about reductionism and emergence and things like that. Again, things that we’ve talked about before on the podcast. I always thought that the reductionism versus emergence debate, to the extent that it was a debate, was kinda boring in the sense that I’m an in-principle reductionist. Like if I knew the standard model of particle physics and Einstein’s General Relativity, in principle, I could do everything but obviously in practice, I can’t do those things and it seems like there’s a camp that says “Yes but in principle I could.” and there’s other camp that says “Yes but in practice, I can’t.” And I’m not quite sure why they’re just not agreeing with each other. Do you see any actual disagreement that we should care about here?

0:13:14 JE: Well, I think that this is something I try to take up early on in the book and I don’t think that the point of emergence versus reductionism is irrelevant to the discussion of, let’s say the boundary between life and non-life impeding physical terms but I wouldn’t wanna conflate it with the more of linguistic point about talking about things in biological terms versus physical terms. I do think that when talking about what languages are, there are just some advantages that one language has over talking about the same phenomenon as another.

0:13:52 JE: So while it might be feasible in principle to describe what is going on in a stock market using a molecular dynamics simulation of all the particles that all the people and in the whole economy that’s involved in everything are made of, it’s an extremely unwieldy way of trying to describe that and you put before you a huge stumbling block in trying to make the translations that are necessary, whereas in this other language that we have for talking about the world, that economics is born out of, the vocabulary is naturally suited and even aimed at that discussion and I think similarly that works with biology as well.

0:14:36 JE: So while on the one hand, sometimes translating gets you new insight because there was something about the relationship between things in the biological space of concepts that you couldn’t really give a mechanistic explanation for without resorting to some kind of physical representation of each of those, it’s nonetheless the case that you actually are interested in something called successful cell division or something called DNA damage repair or these things where high level concepts in language are gonna be expressed more effectively if we’re not talking about particle one being at this position and particle two being at that position.

0:15:13 JE: So I don’t think it’s merely just an issue of the difference between reductionism and emergence, I think it’s also about the appropriateness of different languages and that we’re not gonna be as successful in describing the world if we don’t make languages that are appropriate to the task and recognize their limitations and their advantages.

0:15:34 SC: Good yeah.

0:15:36 JE: That being said, I also think… We’re talking about reductionism and emergence, that’s clearly relevant to the discussion with biology viewed through the lens of physics because life is a portion of the world that you kind of wanna draw a box around and say “Can I explain what this thing is as a phenomenon in the same way that I can explain the transition from a liquid to a solid or the same way that I can explain some more exotic behavior of a collective of particles that you see in… I don’t know, fractional quantum hall effect or whatever.

0:16:12 JE: There are these things that Physics has been very good at making sense of, where they see emergent predictability and describability coming at a different scale than the microscopic description of the individual degrees of freedom out of which it seems like the phenomenon gets going and clearly life has the potential to be addressed in that way, at least in principle. The thing that I would point to as a difference though is that life is a much more multifarious semantic bundle than the physical phenomena that we typically refer to when we talk about classic examples of emergence.

0:16:49 JE: So as an example, if I talk about the liquid vapor transition, this classic model of a higher level description of a many body phenomenon, many particles and in some sense, I’m missing the forest for the trees if I look at every position and of every particle ’cause I realize there’s some order parameter, some single number or a few numbers that describe a lot of what’s going on as I change the temperature and I have tremendous predictive power once I realize that hidden simplicity. I think one of the things that is in some sense, a psychological… I don’t wanna say impediment but at least kind of that leads a little bit in a misleading direction in the culture of condensed matter physics when trying to come to biology is that we often are looking for symmetry to take something that looks complicated and revealed to us, it’s extremely simple.

0:17:42 JE: But living things are characteristically highly unsymmetrical and very messy and very hierarchical in the communication between different scales of links and energy and time and so you don’t get to just write down a very simple, beautiful theory that realizes that only one link scale matters or only one energy scale matters or things where emergence and classic examples in condensed matter physics really succeeds.

0:18:10 JE: And the approach that I’ve tried to advocate for, which I think has been somewhat successful so far, we’ll see and at least I’ve found it illuminating, is to say “Let’s take that multifarious bundle of what life is and try to chop it apart into a set of distinctive life-like behaviors so behaviors that we think of as being indicative of life-likeness even if they aren’t unique to life.

0:18:34 JE: The things I would put on that list are making copies of yourself, self-replication on the one hand or harvesting energy from a difficult to access source in your environment on the other hand or acting in a way that embodies an accurate prediction of your future based on the statistics of you’re past. These are each things where you might imagine something that’s not alive but which is quite successful at doing this activity and which looks somewhat impressive and if you bundle them all together, it starts to be like oh, maybe we’re talking about a living thing if it copies itself, it predicts it’s future. It’s harvesting energy.

0:19:16 JE: But at the end of the day, we’re looking through the lens of physics, life looks like a grab bag of these specialized behaviors from the perspective of physics and it’s okay just to say, let’s treat them one by one and start asking, can I make a physical theory of what permits or forbids or causes the emergence of self-replicators. Can I make a physical theory of what permits or forbids or leads to the emergence of self-organized prediction of the environment and I won’t say in each case that I’m describing the boundary between life and non life but I’m certainly going to make better sense of that in the language of physics by engaging in that work.

0:19:52 SC: Yeah actually, it’s interesting because I had a Stuart Bartlett who is an astrobiologist. Heavy oogenesis researcher on the podcast and he and Michael Wong have proposed a four-part definition of things that are involved with life and basically you mentioned three replication, energy harvesting, prediction and they add to that, some form of homeostasis but otherwise, with small changes to vocabulary, it’s a very similar thing. So is it a growing feeling in the field that rather than coming up with a once and for all definition of the word life, we can recognize that life has different aspects and study them individually and then hope to put them together?

0:20:31 JE: I suppose I shouldn’t speak for others and speculate too much about how popular this frame yet is but I certainly see the merit of it and I expect that it’s gonna have increasing traction over time because it doesn’t just kick the can down the road but it even, I think, makes a principled argument against trying to define life at the outset before we can start making progress on the science, it’s very hard. If you say The first step is, let’s all agree on what’s alive and what isn’t and then we’ll try to make a theory of that and if instead you’re going to say well, you agree with me that living things make copies of themselves, right?

0:21:15 SC: Right.

0:21:16 JE: Well you agree with me that living things to some degree, behave in ways that embody predictions of their environment and also you mentioned homeostasis, I’m not sure that word appears in the book but there’s a characteristic of life in physical terms that is definitely the focus of one of the later chapters that essentially captures that idea that it’s about how as energy flows through this collection of matter, the energy is sort of powering self-repair and stability and maintenance as opposed to causing disruption and chaotic disorder and that’s not to be taken for granted because a lot of driven non-equilibrium dynamics that you could observe might look that way to you, either in reality or apparently. Especially at the beginning of the flow of energy.

0:22:02 SC: Well yeah, that leads us directly into the next aspect that we wanna bring in, which is the physics side of things, right? You’re trying to work at the interface of biology and thermodynamics or non-equilibrium statistical mechanics, where if we know one thing, if people in the street are aware of one thing is that entropy is increasing in disorder is taking over so how do you fit that aspect into what you think about life?

0:22:27 JE: Yeah so I love this discussion of the Second Law and increasing entropy because I think that the first step in getting into this discussion is to try to argue for an equivalent way of talking that is kind of ready for a new century of non-equilibrium statistical mechanics and focuses the language in the right way so the ways that people have talked about entropy in the past, I think are very much born from the early history of thermodynamics and what it was possible to work with experimentally and what it was possible to predict with that and we have the second law of thermodynamics, the idea that entropy is always increasing and so therefore there’s always gonna be increasing disorder.

0:23:15 JE: It becomes a kind of this old chestnut where it goes out into popular understanding and becomes this kind of un-rigorous idea which on the one hand, conforms to our intuition in a variety of cases ’cause we all know that rooms get messy unless you’re kind of invest effort in them somehow and sand castles fall down, etcetera but at the same time, we’re just confronted by a world where we constantly see examples of things where the internal entry, meaning the amount of order within the system is decreasing and so sometimes entropy locally increases, sometimes it… Sorry. Sometimes it locally decreases. Sometimes it locally increases.

0:23:52 JE: So let’s just step back and instead of talking about it in those terms, let’s say this, whenever people talk about entropy, what they’re really talking about is counting the number of ways something can happen and that is ultimately of interest to us as far as predicting the world because it has an impact on the likelihood of certain things happening but it is not the only factor that determines likelihood in some kind of probabilistic model that we’re going to make.

0:24:22 JE: So in the classic discussion of entropy that you’re trying to introduce the idea to, I don’t know, someone in a high school Chemistry class you’d say well, suppose we count the number of ways of collecting all the air molecules in the corner of the room and we also count the number of ways of spreading all the air molecules in the room over the whole room, clearly there are many more ways of spreading the air over the whole room and so it’s much more likely that the air will spread out over the whole room so you don’t have to worry about a spontaneous vacuum just choking you and that’s very reassuring and it seems like what we’re saying is high entropy things are what’s likely but actually that’s a specialized scenario of a particular assumption that we’re making.

0:25:04 JE: We’re assuming the dynamics of the molecules in the room have been just getting to be sort of chaotic and explore the space of all possible combinations and arrangements for a long time on some measure of what long and short is in time but of course you can take a pump and pump all the air into a much smaller space if you do work on the system, you’re allowed to make a vacuum and so you’re lowering the entropy of that air and that’s physically permissible as well so the dynamics of a system where pumping is going on, you’re allowed to have a local decrease in entropy.

0:25:37 JE: So I think that I very much focused on talking about systems in this open system frame where you say, I am my working material and I both can think about possible random fluctuations coming from… I’m at some temperature, I’m in a heat bath, there are lots of things at the molecular scale randomly banging into me but I also have something else outside of me that’s part of my environment that might be doing work on me of a more organized sort. It’s imparting energy to the system that has some organization to it itself, like maybe a pump or maybe an optical stimulus or something like that and once I’m talking in those terms, the new way of talking about this, which I think allows us to dispense to a large degree with the discussion of entropy, at least at the outset, is to say what’s the probability of one outcome versus another outcome?

0:26:26 JE: That’s how we should be talking about it because then what we can notice is that some outcomes will be likely because they’re messy and there’s more ways for them to happen and that is the weight of entropy on the scale but there are other outcomes that might be likely to happen even though they’re low entropy but instead it’s because work or other energy exchange is really powering going to low entropy so we see already examples of that in equilibrium statistical mechanics because I can have a low entropy outcome called crystallization happen if I just cool down a liquid and I don’t wonder how that works, it’s just that the attractive forces between the molecules can overwhelm the pole so to speak, of being at higher entropy.

0:27:10 JE: And in this non-equilibrium world, I don’t just get to exploit attractive interactions, I also have the possible patterning influence of external forces that are changing over time and pushing on me and biasing my evolution through a space of possible configurations.

0:27:27 SC: Yeah. I think actually, that’s a wonderful explanation but it’s probably even worth elaborating on a little bit, just because I think that a lot of people… One of the things that is hard for outsiders who are not professional scientists to get is sort of the lay of the land in terms of what ideas people think are interesting and talk about. I mean the second law says that entropy increases in a closed system and what you’re pointing out which is sort of obviously true, is that most systems are open, right?

0:27:54 SC: We interact with the rest of the world and this whole idea that we should… Should and can think about laws of thermodynamics and statistical mechanics so that apply to these open systems is kind of new. It’s not… It’s something that people always knew but the taking it seriously aspect with things like fluctuations theorem, the Jarzynski equality is a famous one. This is cutting edge stuff in non-equilibrium stat-mech.

0:28:25 JE: Yeah and so I think since you refer to the Jarzynski relation and there’s a related result from Gavin Crooks that I think gets explicit mention in the discussion in the book. These fluctuation theorems, what they really did to transform the way people think about non-equilibrium statistical mechanics is that I think the early history of non-equilibrium thinking, coming from the early to mid-20th century was very much trying to take the macroscopic language of equilibrium thermodynamics that had succeeded in the 19th century so brilliantly and try to find a non-equilibrium generalization of that and people like Ensager and Prigogine were somewhat successful at talking about that in the linear response regime where you’re basically close to thermal equilibrium.

0:29:14 JE: But I think what was hard is that the real success in generalizing the ideas of statistical mechanics wasn’t going to really catch fire until you could talk about the microscopics and there was, I think both not as much reason to talk about the microscopics when you couldn’t do simulations and when you could measure much less and also there was kind of a cultural hold over of wanting to talk in terms of macroscopic state variables because that was how equilibrium thermodynamics got going.

0:29:45 JE: But then what happened, I think partly… I think likely driven in part by the emergence of a literature of numerical simulation in the 90s, was that you started to have practical questions you were asking just about your simulations of stuff that was trying to show you the microscopic dynamics of particles while they were at some temperature and had some rules of how they pushed on each other so you’re simulating physics and now you don’t just wanna know the likelihood of a state like you’re asking an equilibrium at some temperature, am I more likely to be at high energy or a low energy?

0:30:20 JE: Instead you’re asking what’s the likelihood of trajectories of a whole movie of the system and the real insight, I think that changes how we can talk about this, which has been driven by work by people like Gavin Crooks and Chris Rosinski and others is to talk about the relative probabilities of trajectories, like the crux result is saying. If I see a movie of a driven system and the time reverse movie, the rewind movie, how likely, relatively, are these two different movies in the dynamics that I’m observing.

0:30:50 JE: And then there’s a rigorous thermodynamic result about heat exchange with the surroundings that tells you basically that the one that’s more likely is the movie that puts positive amounts of heat into the surroundings and then the Jarzynski result is in a sense a special case of the Crux result but one that really at an earlier point, several years earlier just blew people’s minds because of what it was connecting where it saw that the statistics of all the different ways that you could measure work being done in the system over repeated experiments could actually connect you back to quantities that you’d be measuring without doing work on the system in a finite time but instead just doing it really slowly at thermal equilibrium and it was suddenly revealing to people that there was all of this information in the seemingly messy and unexplainable stochastic random noisiness of the non-equilibrium setting where you’re driving the system and it does something different every time.

0:31:52 JE: And there was a connection back to the language of equilibrium thermodynamics and so if you take those results and put them together, you can pretty easily rearrange them and get something that looks sort of like a Jarzynski-like result that is really derived from the Crux relation, that generalizes the idea of what is the probability of a given outcome for your system, given that it starts in a certain place and you no longer are just saying “Oh well, lower energy is more likely.” ’cause that’s the adjusted thermal equilibrium result, if you just have thermal fluctuations.

0:32:26 JE: Instead, you’re starting to say, there’s this work history contribution, there’s this question of how much work is done every time I go from some starting state to some ending state and all the different ways that could happen, how much energy gets dumped into the system by the pattern sources in the environment and if I collect together the statistics of all those different ways of doing work, there’s actually information hidden there for me about the likelihood of one outcome over another one and now we’re talking essentially about an evolutionary result, where we can say, I think this evolutionary result is more likely than that evolutionary result.

0:33:02 SC: Yeah and this is a perfect sort of segway so I think that you’ve done this before, perhaps you’ve written a book about this ’cause you’ve clearly practiced this sort of dialogue. So the idea of the Crux and Jarzynski results in non-linear stat-mech is, don’t just say here’s the average or most likely thing, take seriously the idea there are fluctuations around this most likely thing and clearly life and biology is plausibly in that regime. So how do you take this sort of evolutionary picture where you think about trajectories rather than just states and apply it to life which is evolutionary in a slightly different sense.

0:33:41 JE: Yeah. So one thing, I think this is an opportunity for me to put out there is that it’s helpful to start by asking ourselves, what is distinctive and different about life that we can’t do in thermal equilibrium. So in thermal equilibrium, we’re sitting at some temperature, we’re getting randomly kicked by our environment and we can basically do two things. We can concertedly roll downhill an energy and that’s happening because the forces on the system are pushing it that way, that’s the definition of rolling downhill an energy and then we can also get randomly kicked uphill by the bombardment of thermal fluctuations from our environment.

0:34:16 JE: And it’s true, as I mentioned before, that you can go to orderly states in that setting, you can form a crystal, for example, as long as the lowering of energy is decisive enough in overwhelming the tendency for the random kicks to sort of scramble the whole arrangement of all the building blocks in the system.

0:34:33 JE: However, if you do that and you do it in a way where all of these building blocks are kind of randomly diffusing around and finding each other and sticking together and then once they find each other and they’re very stable, what you’ve done is you’ve made something that’s gonna be extremely hard to rearrange once it had formed. So you can make orderly structures but they tend to be very inert by virtue of how orderly they are. That orderliness and inertness are… They’re going hand-in-hand in thermal equilibrium.

0:35:05 JE: But when you look at living things, what’s striking about them is not that they just seem especially order, like that they’re in some exceptionally rare arrangement of their constituent parts but also that they can rapidly rearrange into such special states but then stay in them very stably for a long time until they sense something else and then they can change rapidly again and so there’s this combination of dynamism on the one hand, with stability when it’s desired and order when it’s needed and you just can’t buy that for love or money of thermal equilibrium. You need a system that has work being dumped into it all the time in order for that to be permitted by basic laws that we used to describe the physical dynamics that we observe in these kinds of systems.

0:35:50 JE: All that being said, now you start to say, let me look at the characteristic life-like behaviors. Making copies of yourself. That requires you to make a copy of yourself more rapidly than that copy falls apart so there’s a kind of error of timing there that you can might be tickling your nose a little bit and indeed what that means is that that has to be powered by irreversible dissipation. You have to absorb work from some source and then dissipate it as heat in order to be able to do that.

0:36:18 JE: Similarly, we have some kind of energy harvesting behavior in your system where I change the environment to have a particular pattern to it and I rapidly rearrange things about my system to be better at absorbing energy from that pattern, for example but then I stay in that state for a long time and yet I couldn’t… Again, dynamically rearrange, if I change the pattern. That kind of dynamism is again, hard to achieve if you’re forming a crystal at equilibrium and indeed in an equilibrium setting, there’s even no such thing as a relationship to a changeable pattern in the environment ’cause the environment in an equilibrium system is static and is just kind of a constant force pushing you a certain way.

0:37:03 JE: So all the things when we go through these distinctive life-like behaviors, what we find is we have to be talking about a non-equilibrium system and it’s maybe gonna be valuable to now have a general theoretical frame that says “how do I write down an equation that tells me about what factors affect the likelihood of outcomes in that setting?”

0:37:22 SC: Yeah and so I certainly buy, I mean something I talked about before also, that there’s these extremes of super duper order, super duper disorder, which are both kind of boring, right? There’s not a lot of interesting room for complexity happening there and in between is where things can happen that are interesting and complex, including life but that still doesn’t quite address the question of the likelihood or inevitability of that happening. Do you think we’ve learned anything about when these complex structures come to exist and does it actually say anything about the likelihood or inevitability of life arising under the right circumstances?

0:38:03 JE: Yeah, I do, although I think that I would break that question into two pieces because there’s the question of the likelihood of life arising and I think whenever we say that, we immediately are thinking about this first moment where something we wanna call life comes onto the scene and that question as a forensic enterprise, working backward is more complicated for a number of reasons but I think if I can start and I can return to that subject but if I can start by first saying, let me talk about an individual life-like behavior.

0:38:35 SC: Sure.

0:38:36 JE: What do I mean by talking about the likely conditions for the emergence of a given life-like behavior? There I think it’s easier to define the question in physical terms and it’s also possible to in simulation and even in experiment to start to demonstrate “Okay, how does this happen? How do I get predictive control over a process like this where I can see it happening so to speak, on a table top.”

0:38:57 JE: So the example that I’ll talk about to start with but I think it’s not the most essential feature of life or not the only one certainly is self-organized energy harvesting so we did a paper in Physical Review Letters several years ago, which considered a model of a simple mechanical system, where it was just a bunch of masses and springs that were sort of hooking and unhooking to each other in a random thermal bath and so the masses and springs are these kind of dominert particles that just have the ability to entangle and disentangle from each other and then they form this kind of mesh of resonator of different random connections between falls and springs and then you could take a piece of that and start shaking it and you can shake it at a particular frequency for example.

0:39:45 JE: So if you didn’t shake it, you would just get thermal equilibrium, you just get some random massive balls hooking and unhooking from each other with springs that would be determined just by the energies of the states eventually, if you reached thermal equilibrium but once you start shaking part of the system and you choose, for example, a particular frequency, now you have energy flowing in from the forcing that you’re giving to the system but the flow of that energy through the system is gonna impact it’s evolution.

0:40:14 JE: It’s gonna impact the exploration of this high dimensional space of possible combinations of a bunch of simple building blocks and with very simple rules for interaction among these different mechanical pieces, you can get a situation where you pick a frequency, you wiggle part of the system at that frequency and then what you end up seeing before too long is a particular evolutionary outcome, not a single microscopic arrangement but a family of possible outcomes that have a specialized ability to absorb more energy from that particular frequency and so in the same way that I might imagine, if I need to be able as a living thing to fly, I’m gonna probably have to have wings of some kind but there are ways of doing it that a bird does it or there’s a way of doing it that a fly does it and they’re not the same.

0:41:04 JE: Similarly, there are aspects of this that have a flavor of physical adaptation because the individual structure I see at the end of this process will always be unique ’cause the space of possible things to explore in combinations is so vast that if I do the same experiment over again, I’ll never get the same result but the commonality they have is that they all can absorb energy much better from the environment that they’re in, in a way that’s finally matched to some characteristic of that environment, like a frequency that is being used to force the system, they can all absorb energy much better than a random arrangement of their constituent parts.

0:41:43 JE: And so I would point to that as a hallmark of something that looks like a foreign function relationship. In biology, we take function for granted as it helps you to survive and reproduce and in physics, we don’t give function a priority ’cause it’s just stuff flying around and banging into each other but what you at least can recognize in this kind of a system is exceptionality of the outcome in it’s physical relationship to it’s environment.

0:42:06 JE: There’s a fine-tune sense in which this is a highly non-random arrangement of many constituent parts that has an exceptional ability with regard to energy flow from the environment.

0:42:17 SC: Yeah, I guess there’s… I’m almost there with you. I think I’m totally there with you in the whole big picture but there’s a bit of intuition that I’ve struggled to develop and not quite succeeded here. When people say that in a closed system entropy increases and why? Well, entropy corresponds to the number of ways you can arrange the system so that it looks the same so there are more ways to be high entropy than to be low entropy, that makes sense to me and now you’re saying that certain arrangements of little sub-systems have a better ability to absorb energy.

0:42:48 SC: Other people have said certain complex catalyzed reactions will increase the entropy production rate faster but I’m missing a bit of intuition as to why I should care [chuckle] about that. What is the rule that says, I should absorb energy as fast as possible?

0:43:04 JE: Well, in fact and this is a very important point, there is no such rule because it is still a system-specific property in the sense that sometimes you can get feedback that leads to what looks like an energy harvesting behavior that self-organizes and it has to do with so to speak, the particular chemical rules or physical rules for how the pieces of a system interact, what kinds of springs are tangling with each other and then you can also devise a system, which we’ve studied as well and there’s a more recent paper we have about this, where you get the opposite kind of emerging fine-tuning.

0:43:38 JE: So you can also have self-organized, fine-tuned being bad at absorbing energy from a particular environment and when we hear that, at first we don’t think that we’re talking about a living thing because we think all living things need to eat and they’re good at that but I think that actual outcome is much more linked to the homeostasis aspect of life. I could unpack that a little bit further down the line but just before diving into the details of that example, I think the other thing that I’ve still left missing, in what I’ve described so far is I’ve been telling you about examples that are empirical that we’ve studied in simulation where it does something but the question is, what is the insight that allows you to say “I can predict generally in this class of systems, which way things are gonna go.”

0:44:29 JE: And I start to be able to know what to expect and why does it happen this way? And I think that the way to understand it is this, that if I have a combination of a bunch of different building blocks, I can think of some combination of them as being like the location of a ball in a landscape, in a mountain range, where my height in that landscape is my energy.

0:44:51 JE: So it’s very close to the real intuition that you’d have for an actual ball in an actual mountain range, except for the fact that you have many more dimensions than three. You have lots of dimensions because you have lots of particles that you’re assembling together and so to summarize the location… To use the location of a ball to summarize the configuration of 10 to the 23 particles or whatever, you need a very dimensional landscape that they’re exploring. So if I don’t have an external environment that pushes on me with some pattern forcing, then all I can really do, as I said before, is roll downhill and get kicked randomly back up hill and then after a time, I’ll tend to go down hill and stay down hill, unless there really are just many more ways of randomly staying up hill so it’s just a classic trade-off between low energy and high entropy.

0:45:40 JE: But if I now start pushing on the system with an external source of work, the way I should think about how this game changes is now, it’s like I’ve put ski lifts or escalators in this landscape and there are particular configurations I can be in, where the way the absorbed energy from the environment is gonna have an impact at how much they can get lifted up some mountain side and dropped down the other. Why is that important?

0:46:05 JE: That’s important because if you are lifted up a very tall mountain and then you fall down the other side but there’s no ski lift on the other side or there’s no escalator on the other side, then you’re stuck, you can’t go back the way that you came and the more that statistical irreversibility ends up being felt in the evolution of the system, the more it’s the case that the most indelible marks, the most irreversible changes in how the system, in a biased way, explores the space of possible shapes accumulates overtime.

0:46:37 JE: Those are gonna be the result of having been in shapes that happened to be good at absorbing energy from the particular environment. So it’s still gonna break into cases whether that leads you to an outcome that ends up being exceptionally bad at absorbing energy or an outcome that leads to being exceptionally good at absorbing energy ’cause it has to do with the shape of the landscape and the pattern of forcing. So you can get into the details of how it breaks out into those cases but the unifying idea, which I’ve called dissipative adaptation, in some things I’ve written about this, is that you think about the outcome structure, the outcome combination of building blocks in your system as being the result of a biased exploration of the space of possibilities where the history of moments in it’s past when it absorbed energy from the environment in a way that involves some kind of matching between it’s structure and the pattern of the environment, that the accumulated effect of those moments ends up being a signature you see in the structure you end up getting knocked into by this whole process.

0:47:41 JE: I guess zooming just back out to the point you were making about entropy, I think the key thing here is that being in a low-entropy configuration, I could be in this kind of a scenario in a high energy and highly dynamic sub-portion of this mountain range or this landscape, as long as the pattern of the way the system is being driven just can’t kick me out of this very strange kind of plateau or Mesa or what have you in this landscape. It previously would have been the case that random kicks would eventually always knock me downhill, if there was far enough to fall that I could really go to low energy but what’s so impressive to us in general, with a lot of things living things are doing, is that because there’s a pattern input of some kind, they can be knocked uphill into these low entropy arrangements that are trapped in some high mountain pass that has a special shape that’s matched to the way the system is being pushed on.

0:48:46 SC: But it does sound like maybe reading too much into this, that there’s a slightly deflationary answer here to my original question in the sense that sometimes structures like this will form, sometimes they won’t and it might be hard or impossible to get a general principle that is ethical over all kinds of systems rather than looking at it at a more fine-grained level.

0:49:11 JE: Well, I think that what we need to think about is, if you look at real life that we know and what makes it tick, part of what always is intimidating to theoretical physicists when trying to say “How am I gonna explain how something like this comes into being?” is how messy it feels that there are many link skills, many time skills, many energy skills that are involved and part of the reason that that’s there is because that reflects this tremendous combinatorial diversity of the particular physical chemical interactions that are possible in the working material that we’re working with.

0:49:48 JE: So I have in a living thing, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, sulphur, phosphorus, various other kinds of atoms in lower trace amounts, etcetera and those have particular ways they can combine that are tremendously diverse in the kinds of properties they can have. If I device for you instead an experiment where I said “All you have is, I don’t know, xenon, just xenon.” [chuckle] and you have to make everything that you’re gonna make out of combinations of xenon atoms. It might be really hard, it might be. It might so happen to be that at least on the time scale you’re willing to wait or given the energy skills you’re willing to make use of, that there aren’t really a lot of ways of putting xenon atoms together that are gonna be qualitatively different in how they respond to inputs from the environment.

0:50:35 JE: So I will happily admit that an essential thing in understanding life likeness is that in order for it to be really striking, there needs to be novelty through combination coming from how building blocks can be put together in different ways so that they really are quite distinct in how they react to the same environment and there are physical scenarios you can devise where maybe the effective chemical diversity or whatever you wanna call it, the effective nobleness and distinctiveness of that whole energy landscape and all the different corners of it being different is just not different enough. You don’t have enough books out of that library to choose from that you’re gonna be impressed by what the non-equilibrium driving gets you at the end.

0:51:22 JE: And the last thing I’ll say is that the other aspect of this is that it may be that the way you’re driving the system doesn’t yet have enough of a distinctive pattern ’cause if you’re not driving the system with a pattern that has enough of a bar code to it, that has enough of a particular structure to it, you may also be at a loss to recognize what it means to be finely tuned to that. So if the only thing I’m doing, for example, is heating one side of the system and cooling the other side of a system, it is a non-equilibrium system and I can get cool-looking worlds that emerge in a fluid as a result of doing that but how many numbers did I need to use to describe that non-equilibrium driving, such that I now I could say “Oh, look at the state the system is in.”

0:52:08 JE: It’s extremely finely tuned to my choice of how I’m driving the system, in a way where random rearrangements of all of these molecules in the fluid would look dramatically ill-suited to doing whatever it is that this particular set of convection cells is doing. I actually haven’t studied the Rayleigh-Barnard system that I’m referring to very much and so I don’t wanna rule out the possibility that some kind of fine tuning could be recognized there but I do think it’s a choice about not only the potential for novel combinations in the working material but also the complexity of the statistics of the external environment that would allow us to say “Wow, this is really well-adapted because the higher dimensional the complexity is of that environment, the more we’ll be able to recognize an exceptional relationship.”

0:52:57 SC: Does this kind of reasoning have implications for things like the anthropic principle for the fine tuning of the laws of nature. Where do you come down on thinking that if the constants in the standard model had been very different, life would be impossible?

0:53:12 JE: So I usually try not to rush to make declarations like that because I do think sometimes through kinds of physical emergence that we’re aware of, you can sometimes get things at higher scales that don’t seem built into the simple interaction. So for example, I could have a fluid that is just made of one kind of particle and if I just look at the behavior of that fluid in a very kind of naive equilibrium stat-mech sort of way, it kinda looks like there’s only one energy scale for how the particles interact and I can’t really make a hand that grabs onto something ’cause whatever it grabs onto, it will just fuse with and so you can’t build interesting things out of one energy scale but then of course, if it becomes a fluid that’s in the turbulent regime and I have all this hierarchy of scales of energy cascades between different sales, if it starts to be that if I look at emergent levels of organization, the fluid perhaps I shouldn’t rule out the possibility [chuckle] that something can be happening there, that it is though I got a new chemistry at a higher scale as an emergent property of something that had very unappealing chemical simplicity at some shorter scale.

0:54:26 JE: So as a physicist, I wanna be very naïve and cautious, both about that and also about what it means to consider the stochastic process of choosing physical constants because you need a model of how universes are made in order for that to make sense and that’s certainly not something I should claim to be expert in and also something I think has a fundamental philosophical challenge hiding in the background but that being said, I do think I could imagine a situation where at least we’re talking more practically and we’re saying we’re gonna fly around and look at planets and trying to see which ones we should be expecting to find life in, while it may be true that you don’t necessarily need exactly what we have here to make something like what we are in life, it might also be that if we found a planet that was mono-atomic in it’s composition, which is made of xenon or something that I’d say “Let’s look somewhere else first, if we have to choose.” because that sounds to me like the diverse space possible combinations could just be more limiting.

0:55:36 SC: I think I’m gonna get angry comments on YouTube from people from the Xenon planet here that we’re disrespecting them but I wanna not skip over something you mentioned and maybe didn’t quite complete. This idea of not just life coming into existence but it’s maintenance, it’s metabolism, homeostasis. There are lessons there. I wanna make sure that you had a chance to say what you wanted to say.

0:56:00 JE: Yeah, absolutely. So we talked a little bit about an example of a system that has a self-organized ability to absorb more energy from environmental pattern and I think that we always are looking for that in life because all examples of like we know are self-replicators and self-replicators do need to eat and so getting better at getting access to food is always one of the things for Darwinian reasons that we expect to see that in living things that we know but there’s another thing living things do which I would argue is an equally impressive, fine-tuned, self-organized life-like behavior, rather excuse me, I should say it is an equally impressive life-like behavior whose self-organization is we’re studying and that’s how you get something that you might wanna call self-repair or homeostasis that has also a highly adapted relationship to a given environment.

0:56:54 JE: So what do I mean by that? Well think about a living thing in the following way, it’s true that in order to live, I need energy input, I need to eat but it’s not true that I’m equally eager to gain access for that purpose to all sources of energy. I can’t just say instead of a sandwich today, I’m going to get an equivalent dose and jewels of GAMA radiation or TNT or whatever. That doesn’t work because actually most arbitrarily chosen ways of putting energy into a system are gonna be like a bowl in a china shop. Energy is just motion or the potential promotion, if you’re talking in Newtonian terms and that’s really the relevant intuition for this discussion. If I dump energy into a system and just give it to parts of the system in no particular way, I’m gonna be activating a bunch of different random rearrangements in different parts and in a living thing, we call that damage.

0:57:45 JE: So that’s why swallowing a stick of dynamite or getting dosed with radiation or whatever is generally thought of as being not conducive to health because living things are in a very small corner of their possible configuration space. They’re highly non-random, especially exceptional combinations of their constituent parts and if you start doing the more random exploration of the space of possibilities there, you’re gonna stop being a frog or you’re gonna stop being a person and start being a pile of carbon actors and oxygen, etcetera with no particular provenance. So you don’t wanna do that and now, when you look at the living thing, what’s remarkable from that perspective is there is a way of delivering energy into the system that doesn’t have this effect by and large.

0:58:33 JE: That as energy flows through it isn’t a bowl in a china shop. That if I get it from the right kinda source, a source for the right pattern, which in the case of people is energy in the form of chemical bonds of certain kinds in the food that we eat and the case of plants, it’s a spectrum of photons of certain colors, then you’re okay and you can take that and use it to spin all the water wheels and suddenly the energy flow is conducive to health and you’re using it to fix yourself and maintain yourself in this specially chosen high mountain pass in the landscape of possibilities. Where if you didn’t have this energy source constantly kicking you up hill in the right direction, you’d fall down and die, you’d roll down towards thermal equilibrium an eventually fall to pieces enough that you wouldn’t be alive anymore.

0:59:22 JE: So if we’re talking about things in those terms, now we have a very good mechanistic understanding of how you can self-organize that kind of relationship to a pattern environment. If you have a collection of particles that are in some landscape of possibilities with different energies and there’s this disorder of interactions between them that gives a kind of effective chemical diversity to how these different pieces combine and you start, for example, beaming a stimulus of a certain frequency into the system.

0:59:53 JE: So that’s like light of a certain color or a song of a certain pitch and then you watch how the system jumps around while it’s exploring it’s space of possibilities, what you see and this is in a paper that we’ve just re-submitted but it’s already on the archive and the lead author is Dr Yiddish Kidia and also another paper in the archive by a graduate student at MIT Newjacob Gold where we were looking at different kinds of systems like this.

1:00:19 JE: If you have a patterned input such as a particular frequency and you take a disorder set of interacting pieces that have lots of different possible ways of liking to move the environment depending on what corner of their configuration space they’re currently stuck in, then in the short term, you absorb a lot of energy, the system jumps around, it rearranges, it changes it’s shape and in the longer term, it learns how to absorb less energy from that environment and it fine tunes away from high energy absorption. It finds a state which is still an excited state, that’s at higher energy than what you get at the equilibrium temperature that you’re subjecting the system to.

1:01:01 JE: It’s still an excited state but it’s a state that somehow in the way that it’s emotions are being excited by the energy flow, just stays in this low dimensional correlated objective that’s coordinating the motion of all these different particles together such that they stay matched to the particular pattern of the source and then if you change the pattern of that forcing, you could change the frequency, you could change things about the directions of which parts of the system are getting poked and pushed in different ways.

1:01:32 JE: Then you see again, this transient re-arrangement and things get scrambled. So it’s like you’ve switched from plants that live off of X-rays to plants that live off of GAMA rays or what have you and now suddenly everything is blown to smithereens and you rearrange, you find a new quiet and state and now again, you’re in this excited state, that looks like it’s using the energy that it’s absorbing to maintain itself in the matched way to the pattern of that particular source.

1:01:57 SC: A lot of people, a lot of scientists, when they see the kinds of things you’re talking about where you can dig into something as manifestly inscrutable and menethible as the meaning of life. The meaning of the word life not why we’re here but they’ll say that, Oh look, we’re on the road to just explaining all of this stuff on purely naturalistic truly physicalistic terms. You’ve already alluded to the fact that a lot of people will do that and that you do not want to do that, you wanna swim against the tide a little bit here.

1:02:28 SC: I will confess, I think that most of my listeners already know that I totally do that. I wrote a whole book, the big picture on how naturalism is good enough for explaining the world as far as we can tell, even though that’s a lot it hasn’t done yet. You wanna put in an alternative perspective so I don’t wanna put in words in your mouth ’cause I know that this is an easy thing to get wrong, the caricature, the straw man. So tell us in your own words how you think about this relationship between religious ideas and scientific ones.

1:02:57 JE: Sure. I guess the one way of putting it is to say when I decided to write this book, I had an awareness that this part of the discussion was always a potential way things could roll once you put a bunch of ideas out there and so I didn’t want to seem naive about that and I didn’t want to start just only focusing on the scientific discussion without in a sense weighing in and saying and here’s the wrapping and the broader context in which I wanna put that and I think because of that, I thought, okay well so I have a personal direction I’m coming from.

1:03:40 JE: In adulthood, after growing up as a physicist, started studying the Torah a lot and being very interested in being a Jew and actually ultimately studied to become an orthodox rabbi and I am interested in that perspective on the world and the human condition and it informs a lot of how I think about what I’m doing and why and so that is my way of being comfortable engaging in the philosophical discussions so I thought, okay so I’ll go and look into sources that I am committed to finding authority in and studying the world through that lens and I’ll see what I see.

1:04:14 JE: And I think what ended up coming out in the form that the book took was that on the one hand, I was delighted and I guess somewhat surprised to find part of the Hebrew Bible that really seemed very interested specifically in contemplating the boundary between life and non-life in material terms and not doing that obviously in the language of modern physics but doing it more in the language of the everyday experience of how people, how human beings experience the material world as a bunch of different natural phenomena. Things like water coursing through sediment and producing branch structures or the formation of still flakes or the way in which we can ourselves appreciate without being scientists so to speak, that our bodies are made of stuff that once it breaks off of us starts to seem sort of more like an animate inert dead matter like the dust under our feet and when a human being confronts that, there is the question of alright, what kind of contemplation does that dispose us to?

1:05:26 JE: And I think one thing that I try to treat at the end of the book is one kind of comment about how this makes us feel as experiencers of the human condition but I think if someone even is not interested in that aspect of it and they’re not necessarily coming to the book with any interest per se in what the Bible has to say about anything, I think what I also turn out to me to be exciting and ultimately I felt valuable pedagogically, is that because the Hebrew Bible addresses itself to the unfiltered experience of the individual human being. Not through microscopes, not through telescopes but in this very kind of tangible everyday sense, what is the world seem to be like from the perspective of a person that it’s contemplation of this topic ends up being expressed in terms of things that are very tangible and relatable and as a result, we have these kind of conceptual talismans where you say, alright, how am I gonna explain what a non-equilibrium system exploring a space of possible combinations with an external drive is like for someone in terms that feel very broadly accessible to everyday human experience?

1:06:34 JE: Well for example, when Moses is given a sign by God of taking the water of the Nile River and pouring it on the drying ground and it becomes blood, that sounds like a parlor trick to a certain kind of ear but if you take it more seriously as knowing about what the world is and say, what kind of point could be hiding there, if we assume in a sense that the text knows how the world works and it’s not dumber than me about that but maybe smarter than me? Then what you start to realize is, this is a very compact metaphorical discussion of what it is for a non-equilibrium system to explore a space of possible combinations because dust of the earth is, yes, is a particulate matter that can be stuck together and in different ways and even dust mixed with water gives you different kinds of mud with different qualitative properties, just depending on the kind of dust and the ratio of dust to water, etcetera.

1:07:34 JE: So you have all these ideas of qualitative emergence and novelty through combination and it’s also perfectly river water that the text is talking about and not just water and river water is water that flows and it’s water that carries energy as well as mass flow and as a result we even see in the world complex emergence branch structures. If you watch water roll through sediment, you can see the emergence of complex branching that reminds one of veins in a leaf or even your own body and it’s not exactly the same process but it’s evocative of much of the same physics that we end up wanting to talk about which is how energy flow can cause particular specialized pages to emerge in space of combinations that are being explored by a bunch of different particles that can clump together in different ways.

1:08:23 JE: So I think ultimately what I hope I’ve achieved in the book is if someone comes to it only being interested in learning about the physics, I actually hope that the use of the frame of biblical narrative, that the chapters are sort of wrapped-in, magnifies their understanding of the physics by giving them tangible equivalents in the everyday world that they can latch on to and at the same time also, I think some people are given to contemplation of the human condition in ways that certainly extend beyond the purview of science and if they’re interested in that discussion then there’s a treatment of that subject coming from my own perspective and certainly it’s gonna express the particular ways that I prefer to grapple with these kinds of questions but hopefully it’s interesting none the less.

1:09:18 SC: Yeah, even in my super atheist book, The Big Picture, I tried to make the point that look, it would be crazy to think that there was nothing of value to be found in religious scriptures or traditions for thousands of years. The most careful thinking about the human condition was done in the context of those conditions, of those traditions but it’s a little bit different to talk about scientific questions versus sort of finding purpose and meaning of life questions. Would you… Just to be super clear to the audience, would you want to say that the Hebrew Bible literally anticipated ideas that we’re now thinking of or can be used to illuminate them by thinking about them in more metaphorical ways?

1:10:01 JE: Well, I think that I would wanna be careful about talking about anticipation in describing what that could mean because I don’t want to advocate for relating to the text of the Hebrew Bible as saying, well because this is a revelation from the hand of the world’s creator, it actually, secretly and ethotheoretically is a science text book if we just decode it in the right way. I think that there’s a long discussion about why that’s not going to be a successful enterprise as a kind of methodology for reading the text and there’s I think, religious arguments against relating the text that way, at least from the perspective that I’m coming from but that being said, I think that this topic has a particular kind of accessibility in that regard because there are some things where if we are gonna talk about how the wave particle duality discovered in quantum theory is going to impact our understanding of how it is that certain optical properties of certain materials we see in everyday experience are actually brought about, you’re more working in a regime where talking about anticipation… I don’t know, I’m not really digging in that place because I’m not even sure what an everyday experience allows us to talk about.

1:11:30 JE: I don’t know that the lime in spectrum of the hydrogen or something like that but I think what’s different here, in comparison to a lot of other things that you can study carefully in physics, gravitational waves with lago or whatever, is that we’re talking about something that there is a lot of empirical knowledge of that is quite qualitative. So while it’s true that we don’t by being material beings living in a material world, we don’t learn statistical mechanics by default, quite the contrary, at the same time, we do know a lot about what it’s like to be alive and we have a lot of qualitative experience of many of the material processes that are relevant to non-equilibrium dynamics that helps us to understand what I think is important to the physics of life likeness.

1:12:19 JE: So by way of contrast, in order to see quantum effects, genuinely quantum effects, you usually need a particularly specialized apparatus that allows you to get to some low temperature or allows you to deal with single electrons being spat out of an oven or single photons that are coming through some source or coming out of some source but if you’re talking about genuinely far from thermal equilibrium instances of self-organization that recapitulation some aspect of life likeness, that isn’t so hard to come by as you’re out for a walk so to speak.

1:13:00 JE: You could trip over, while out for a walk, a hillside where a flood that was caused by rainfall led to some kind of alluvial branching of sediment that was being deposited on… I’ve seen this in a parking lot or something [chuckle] once and that does provoke you to contemplation and it’s not irrelevant to the actual physics that you should be bringing to bear when trying to think about what’s going on in life, even once we get fancier with how you describe the physics at a molecular level. So since we’re working very much in the classical regime where the intuitions of watching a ball bearing fall through honey or not, irrelevant to talking about what it’s like for protein to change shape in viscous fluid like water at low Reynolds number, these things have conceptual relationships to each other.

1:13:53 JE: So all that being said, I think what that means is that even if we’re just talking about things that the human experience can know by intuition from contemplating the question of what it is for life to be built out of materials, which is something that we can see by looking at how lifeless a fingernail is once it falls off of the body, we get the opportunity, perhaps in the wisdom of human kind to develop understanding of what some of these relationships might correspond to out in the world that we observe and you don’t only see this in the Hebrew Bible, you see it in other ancient traditions as well and also I think there’s a fundamental question of adjudicating anticipation versus appeal to intuition of the interpreter is really a very hard thing to define precisely because when we’re interpreting text, we always bring what we know about the world into that interpretation and it can be hard to really control what comes out of the interpretation and define what we injected and what we discovered.

1:15:09 SC: Maybe you can elaborate on one of the points you just made. There are plenty of people who’ll be listening to this and some will be sympathetic to the general idea but they won’t be in a Jewish tradition, they’ll be in something else. Do you think there’s something special about the Hebrew Bible? Or do you think there’s sort of a methodology where by looking at ancient texts of wisdom that we can illuminate ways that we’re thinking about the modern scientific age?

1:15:37 JE: The way that I would put it is certainly the reason that I’m working from that text is because I have commitments to that text perspective on the world that make it the one where I feel kind of obligated to work from if I’m trying to engage with some of the kinds of questions that go beyond the scope of the narrow scientific description and so I didn’t start with a list of different religious traditions and say which one is gonna be best for exiting on equilibrium physics. I know I’m very happy to admit I bring my personal commitments and motivations into that aspect of the discussion and I also don’t want to argue that I know for certain that if we’re gonna lop off just a piece of a given ancient tradition and say what might it be contemplating, that is somewhat universal to the human experience, that there might be a lot of overlap or parallelism that we could establish and you can do this in all sorts of ways, not only in ways that pertain to physics.

1:16:46 JE: So I wouldn’t discourage anyone from looking somewhere else and seeing what they find there if that’s what’s interesting to them but it was kind of an enterprise of interpretation that this is what I had to kind of knowledge and skill for and so it’s where I was looking and I guess I ultimately think also, there may be something that is particularly interesting about the tradition of the Hebrew Bible in regard to this because of it’s Viamonte monotheism at least in the sense that the desire to explain different aspects of the world as the result of different interacting personalities in more polytheistic descriptions probably makes it less likely that you end up thinking of the world as a whole fabric that has kind of a set of rules that one person decided through which you can start to understand it because it may be more likely to represent the world as kind of a quixotic combination of different inscrutable personalities in that case but I think that certainly widens the field beyond what I feel competent to comment on.

1:18:07 SC: Yeah. Do you think… This is going beyond a little bit what we’re talking about here but do you think that there are just sort of principle philosophical reasons to think that a purely scientific naturalist description of the world falls short in terms of a complete explanation? Do you think that people who are scientifically naturalistically inclined are cheating by not offering answers to questions like maybe why there is a universe at all or something like that or is that not the kind of road you go down?