The idea of "red states" and "blue states" burst on the scene during the 2000 U.S. Presidential elections, and has a been a staple of political commentary ever since. But it's become increasingly clear, and increasingly the case, that the real division isn't between different sets of states, but between densely- and sparsely-populated areas. Cities are blue (liberal), suburbs and the countryside are red (conservative). Why did that happen? How does it depend on demographics, economics, and the personality types of individuals? I talk with policy analyst Will Wilkinson about where this division came from, and what it means for the future of the country and the world.

Support Mindscape on Patreon.

Will Wilkinson received an M.A. in philosophy from Northern Illinois University, and an MFA in creative writing from the University of Houston. He has worked for the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and as a research fellow at the Cato Institute, and is currently Vice President of Policy at the Niskanen Center. He has taught at Howard University, the University of Maryland, the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He has written for a wide variety of publications, including The New York Times, The Economist, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, Vox, and The Boston Review, as well as being a regular commentator for Marketplace on public radio.

0:00:00 Sean Carroll: Hello everyone and welcome to the Mindscape podcast. I'm your host, Sean Carroll. We've all heard stories of families living in small towns where the children grow up and make different decisions. Some of them wanna go to the big city and test their fortunes, others wanna stay behind and live a comfortable life within the traditions where their family grew up. This kind of difference between moving to the city and living out in the country, or even the suburbs, is increasingly becoming a major partisan divide, both in the United States and worldwide. As Will Wilkinson puts it in a recent paper he wrote, "There are no Republican cities anymore in the United States. Republicans live in suburbs in the country. Democrats live in urban areas."

0:00:44 SC: Wilkinson is a Vice President for Policy Research at the Niskanen Center in Washington DC, and he's dug into this question in a paper he wrote called, The Density Divide: Urbanization, Polarization, and Populist Backlash. It's not just that people who go to the big cities become liberal and people who stay in the country become conservative, there's interesting cause and effect relationships. What kind of people move to the city? What kind of people leave the city and move to the country? What do changing demographics, immigration and birth rates and so forth, what effects do they have on how people think about the world, not just who they vote for, but their outlook on life, their outlook on other countries, their outlook on the economy?

0:01:27 SC: This difference between city life and suburban and country life is increasingly becoming the important difference between different kinds of people here and elsewhere, and so it's important to dig into how that's happening and why it is. So, let's go.

[music]

0:02:00 SC: Will Wilkinson, welcome to The Mindscape podcast.

0:02:02 Will Wilkinson: Thanks for having me on, Sean.

0:02:04 SC: So, you've written quite a wonderfully interesting research paper about the density divide, which I wanna focus on for the podcast. But first, just to get our listeners oriented as to where we are, why don't you say a little bit about who you are, what perspective you're coming from, and also, I'll give you a chance to plug the Niskanen Center, which is a recent new appearer on the scene.

0:02:27 WW: Great. Well, I am Will Wilkinson. I am the Vice President for Research at the Niskanen Center in Washington, DC. You pronounced it correctly in Finnish. It's a Finnish last name, but the guy we named it after pronounced it Niskanen. So it's the Niskanen Center.

0:02:48 SC: Some of my best friends are Finnish so I do learn a little bit. Yeah.

0:02:51 WW: Yeah, the old, "Some of my best friends are Finnish", line, huh? [chuckle] Yeah. And what we do at the Niskanen Center, we're a think tank. We focus mostly on climate and energy, immigration, welfare and economic and social policy, as well as a few more areas, regulation and so forth. And we've been around about four years, and we started as a moderate libertarian institution. Most of the senior staff at Niskanen are ex-pats from the Cato Institute, which we all left for various reasons. And we have, over the course of the last three years or so, been trying to find our niche and we've become less and less ideological and more and more pragmatic, and just consider ourselves a moderate think tank. But we tend to have a free markety sort of focus, but not in a traditional right of center way. We are big fans of social insurance and the welfare state. One of our themes is how capitalism and the welfare state mesh well together.

0:04:14 SC: So for those who don't know, the Cato Institute is, I take it, slightly more straightforwardly ideological in the sense of being pro-capitalism, libertarian kind of place?

0:04:23 WW: Yes, it is. It's got a very orthodox version of libertarianism that people may be familiar with if they've read Ayn Rand or Robert Nozick or Murray Rothbard. It runs... There's some diversity in views at the Cato Institute, but it's a narrow band that's within a pretty orthodox libertarian perspective. And a lot of us at Niskanen who used to work there, left because we grew out of it in one way or another, started to see that we were making certain errors. One of the nice things about arguing for a living is that you end up encountering people who are smarter than you. [chuckle]

0:05:17 SC: Yeah.

0:05:20 WW: And you can never accept that you lost an argument in the moment, but afterwards, when you're opening the fridge to make a sandwich at two in the morning, and you're thinking about it and you're just like, "Yeah, there's really something wrong with my position." And as you try to work it out, you try to cover the chinks in your armour, you try to shore up your position, and by the time you figure out how to fortify your general position, you find that you've given up something that you had been standing on before. And as you iterate that process, you just actually end up with a pretty comprehensively different set of views over time. But because it seems gradual you don't really notice it, necessarily, right away.

0:06:10 SC: Yeah, actually... This is not what we're here to talk about, but I'm very happy to talk about it 'cause it's awesome. There's the idea of a phase transition in physics, which is very similar to this. And I was always skeptical of things like the backfire effect, where you say that you give someone some piece of evidence against their position and they hold their position more strongly. I'm sure that's true sometimes, but there's clearly a timescale question here. Presumably when they do those psychology tests, they're asking the question right away. And underneath the surface these little thoughts and facts percolate, and then a long time later there can suddenly be, "Whoosh!" You're like, "Oh crap, I gotta change my mind about everything." You might even forget where the initial impetus came from.

0:06:51 WW: Yeah, sometimes I... I think the funny thing psychologically is that... I don't know if it's the same for other people, I know I'm a little bit weird. But I tend to initially resist the idea that I have changed my mind...

0:07:08 SC: Oh, yeah.

0:07:09 WW: When I have. And I think that has something to do with holding the narrative around your self-identity steady in a way. So, there's a resistance to even acknowledging that you changed your mind. You just tend to interpret it in terms of, "Well, I didn't really change my mind so much as I changed the emphasis on this point, and the view that I have now is just a better way to articulate what I thought all along." There's a lot rationalizing that goes into telling yourself what you think, but after a while you start to notice that, "Actually, no. I'm straightforwardly contradicting what I used to say."

0:07:56 SC: The very first episode of the Mindscape Podcast was with Carol Tavris who wrote a wonderful book called Mistakes Were Made but Not By Me, all about how we rationalize every single thing we do. And you're right, just continuing our sense of identity is a big part of it. So but anyway, okay, good. I think we could talk about this for an hour but we have other things to... Other fish to fry. And so in this paper you've written, is... Actually, let me finish the thought of the Niskanen Center. Because I think that a lot of things we're gonna end up saying are gonna seem to the outside observer like slightly critical of Republicans or of right-wing people more generally. But have you been a Republican most of your life? Is that a fair statement?

0:08:42 WW: It's fair to say that I've been on the right for most of my life.

0:08:45 SC: Yeah, okay.

0:08:47 WW: Because I have been a professional Libertarian for most of my professional life. I went to grad school, got some grad degrees in philosophy, and out of that I started working at the Cato Institute. I've also worked at a place called the Marketo Center, which is part of the large network of organizations that are run by the Cokes or by the Coke now. I voted for Republicans before but in most presidential elections I think when I was younger I voted for libertarians. But I voted for Mitt Romney on identity politics grounds. I grew up a sorta Mormon and that was...

0:09:36 SC: Oh.

0:09:37 WW: That's my people, Mitt Romney. [chuckle] I think I might have voted for George W. Bush over Gore, I'm not sure. See this is one of those things...

0:09:50 SC: Your self image has repressed that.

0:09:54 WW: I honestly don't remember, or I might have voted for whoever the Libertarian candidate was. I remember favoring George W. Bush over Kerry, but I don't know who I actually voted for, it might have been the libertarian. But yeah, so most of my professional life I've been in some way a part of the right, and the Libertarian movement is part of this right of center coalition that was initially forged around anti-communism. Libertarians were always the socially liberal part. The most socially liberal part of the right coalition tend to be in favor of drug legalization and the decriminalization of sex work, tend to be anti-war.

0:10:43 WW: So, there's a lot of commonalities with people on the left. And in fact that's one of the reasons why I ended up leaving the Cato Institute is that my colleague, Brink Lindsey, and I had both decided that we were tired of... You know what people call right fusion-ism, and the fusion of social conservatism and more libertarian economic views. At the Cato Institute as libertarians, we would often say that we have just as much in common with people on the left as on the right, but institutionally and just as a matter of the practical political reality, you're hanging out with Republicans, and those are the people you're helping. So we're like, "Well, let's make good on this thing that we say." And so we had a project where we were reaching out to people who worked at think tanks on the left of center, left leading magazines and journals of ideas, and we're building a kind of left fusionist Libertarianism that for a while we called Liberal-tarian-ism, which is a terrible name.

0:11:48 SC: I remember those days, yes. I was paying attention to that.

0:11:53 WW: And that was going okay, and then the Tea Party came along and a lot of people at the Cato institute got super excited about it and thought it was the... The President at Cato at the time had believed that there was something essentially libertarian in the American political culture, and that this strand of our cultural DNA would someday rise up and there would be this great efflorescence of Populous Libertarianism. He thought that Tea-party was his moment, and the stuff that Brink and I were saying was a bit critical of the Tea Party, and all of a sudden our concentration on building this coalition with Democrats seemed counter-productive. And so we had a bit of tension and a parting of the ways over that. But for the most part I've seen myself as part of the right. And what we do at the Niskanen Center mostly, though it's not publicly visible, is we go down on the hill, we work with moderate Republicans on our issue priorities.

0:13:12 WW: And the Trump presidency has been a horror show for us 'cause our main goals are things like getting Republicans to support a carbon tax, getting something like comprehensive immigration reform passed, things like that. [chuckle] And Trump has not been very friendly to those efforts, and the Republican Party under Trump hasn't been friendly to those efforts. But that is where most of our time goes, that we had... And this, I guess, gets to the point of my paper, the genesis of my paper. We, like most everyone, had expected Hilary Clinton to win the election, and we thought that our comparative advantage was gonna be bringing along some moderate Republican votes to support things like legislation on climate change, comprehensive immigration reform, and things like that. And 'cause there's gonna need some Republican votes to get through, we were building the kind of network of allies on the Hill that would be able to make that happen. And then Trump won the election, and we were like, "Oh, no." [laughter] And like a lot of people, I was like, "What the heck happened?" Like what... Something's gone screwy, or we're missing something.

0:14:46 WW: And at this... Just a bit before that, there'd been the big Brexit vote in the UK, and you're starting to see these uprisings of the Populist Right in Europe and elsewhere. And it seemed like a general thing that was going on, and the explanations that I was hearing to account for it weren't that satisfying to me. Like it's a backlash to neoliberalism, or it's a backlash to political correctness, or demographic change in immigration. There was a lot in all of those things that makes some sense, but it seemed somehow bigger than that and more general. So I started digging into the kind of, "Why Trump", question, with an orientation to try and understand where right-leaning populism was coming from, why nationalism was all of a sudden a thing again. It turns out that history didn't end. [laughter]

0:15:56 SC: I've never quite taken it by that one, yeah.

0:15:58 WW: Yeah, and so I was like, "Okay, so what's happening now?" And so the genesis of this paper was trying to understand basically why Trump won the election, but also why Brexit was happening, why Populist Nationalist parties keep winning more and more vote share in even the most liberal European countries. And I hit on a couple of things that I thought had been overlooked. So I dug into them in this paper.

0:16:30 SC: Well, it's especially interesting to me because I'm finding this, a year plus into the podcast, that certain themes keep reappearing even though I talk to very different people about very different things. So the idea of cities and urbanization as a major driver of the future of the world is absolutely one of them. I talked with Jeffrey West who talked about how innovation and creativity are driven by high density populations. And I talked to Joe Walston about how there's this optimistic future where we can save the planet by getting everyone into cities and preserving the environment outside. And now you're saying that, in some sense, major political trends worldwide, and in the United States especially, have a lot to do with urbanization as a phenomenon.

0:17:18 WW: Yeah, that's right. So the thing that really got me started is, after 2016... And it was Jonathan Rodden at Stanford especially, published some things about the relationship between population density and party vote share. And Rodden's stuff, I thought, was just mind-blowing, that there's this very tight, almost linear relationship between higher density, higher Democratic vote share, lower density, higher Republican vote share. If you go to the densest part of any town in the country and then start walking towards the edge of town, it just gets... If you're at the middle of the town, at the densest part, it's the most Democratic part. And if you just kinda walk toward the country, it just gets progressively less Democratic. And then the less dense it gets, the less Democratic it gets, the more Republican it gets. That struck me as crazy. Like how could that be the case? And then the second thing, which relates to an interest that I've had for a long time, in political psychology, in my grad studies... So I was a PhD student in Philosophy, and I studied stuff at the intersection of political philosophy and cognitive science. And I have long been interested in what explains why people have the moral temperaments/dispositions that they do, why people have the kind of political impulses that they have.

0:18:56 WW: So I was aware of all of these literatures that correlate personality types to different political attitudes. And so I was looking at those pictures of the relationship between population density and party vote share, and just mapping that on to what I knew about the relationship between partisan loyalty and left-right ideology and personality. And I was thinking, "Well, if both of those things are true, this means that there has to be... That that gradation along density from less Democratic to more Republican, has to be a gradation in terms of personality as well." And I was like, "Could that be the case?" And I got really interested in that. And the paper started to take shape out of that, like, How did we get this kind of division in our politics? It seems to reflect a real spatial division in where left and right-leaning people end up living.

0:20:22 SC: Yeah, the personality stuff I think is especially fascinating. In fact, listening... I listened to your paper. I listened to the fact... You did an audio book reading of it, which I thought was fantastic because now if you ever have a viral Tweet you can actually say, "Go to my SoundCloud and listen to my reading of this paper." [chuckle] But also, it induced me even to take the big five test online, so we can talk about that...

0:20:46 SC: Oh, great.

0:20:47 SC: Later on, but before we get...

0:20:49 WW: I can guess you, Sean. I've been doing this so much, I...

0:20:53 SC: When we do that, when we get to there, I want you to guess me. 'Cause I guessed myself four out of five, I would say. But let's just emphasize the size of the effect that we're talking about here, 'cause it really is remarkable, before we get to explaining it. A pithy summary is that you say in the paper there are no Republican cities. Which when you put it that way sounds kind of dramatic. And not only that, but it didn't used to be the case. Right? This is a relatively recent phenomenon, but it's extremely strong now.

0:21:25 WW: Yeah, it didn't used to be the case. So in the paper I go through three different mechanisms of sorting. Maybe I should back up a second and just mention the overarching context of urbanization. That is one of the things that I felt was being overlooked in a lot of explanations that I was seeing for just a lot of social developments broadly. If you look at it, urbanization is clearly the most momentous thing that's happened in human social life over the past 200 years. It's this just absolutely immense transformative force. The entire human population has basically filtered itself out from... We used to be really diffusely spread out over the territory when we had agricultural economies that sprinkles people around in a relatively uniform sort of way. But the end of the agricultural economy, the beginning of industrialization, led to this slow shift of the population towards these big concentrated hubs of commerce and trade. And that is a world-wide phenomenon. It's just absolutely immense.

0:23:00 WW: And a lot of people don't realize how big the effect is. In 1790 when the constitution was written, and New York City had 33,000 people in it. And that's about the size of my hometown, which I talk about in my paper in Marshalltown, Iowa, which is just a bit less than 30,000. But now we have just scores of cities that are... Metro areas that are over a million people and all over the world, just populations are continuing to concentrate more and more and more. And that fact has to really mean something. That's gonna make a difference to the way people are relating to each other. And then thinking about that, one of the things that immediately came to mind was Thomas Schelling's work on segregation, which may or may not be familiar to you.

0:24:04 SC: I wrote about it in my book. The Big Picture.

0:24:06 WW: You did. That's awesome, do you wanna explain it, because I can talk...

0:24:11 SC: No no no, this is why we're here. For you to explain it. But, it's a way of explaining segregation even when people have only mildly pro be by my own in group kind of attitudes, right?

0:24:24 WW: Yeah, exactly. Schelling, and if you've... He's a big influence on me, I love Thomas Schelling, he's an economist at Harvard, he won the Nobel Prize for his work in Game Theory and he's got this terrific book called Micromotives and Macrobehavior, is that what it's called? And the whole point of the book is to show how you get aggregate effects out of individual choices. And he's got a very, very simple, elegant model where you could do it on the checker board if you want, you can take the white pieces and the black pieces, and just distribute them on squares randomly. And the rule is that each of the pieces wants to... We're imagining each of the squares as like a house. And so there are eight squares that touch any square unless it's at the edge, right? The up, down, left, right, and both diagonals, and the constraint is everybody...

0:25:41 WW: Nobody minds being in the minority, it's fine to be in the minority, you just want three of those eight squares to be the same type, white or black as you. And so what you have to do is you have to move the... Each piece until it satisfies that constraint. But man, so you do it over and over again 'cause if you move one then it opens up a new space and it violates the condition for some other piece, and as you get them all situated, you find that you've pretty radically segregated the board. And so even this mild preference for homophily as the social scientists call it, homophily is just liking sameness. And that seems to be a pretty deep feature of human psychology that we... Everybody likes people like them. Our friends tend to be people like us, people... It's interesting, people's friends even tend to be the same height they are and stuff like that. So you see homophily in all sorts of different things, and so that's an assumption of sort of uniform weak homophily. And even if...

0:26:49 SC: I talked to Nicholas Christakis on a previous podcast, and he labels it "mild ingroup preference," "mild ingroup bias," or something like that, one of... Something that he says just appears all over the place in the animal kingdom whenever social structures become to exist at all.

0:27:05 WW: Yeah, absolutely. And so if you look at Schelling's experiment, which... With just his little model, and tons of people have done all sorts of elaborations on this, and you can watch them on YouTube, with like people... You can set up a population of millions of reds and blues or whatever you want them to be, and you can change the constraints, but if you use Schelling's assumptions, it can take, if you've got a huge population, it could take millions of rounds, but over time those populations segregate fairly cleanly, not just in half, but you'll get these very clear clusters of reds and blues that are sharply demarcated from one another. And... But those assumptions again are weak, that's weak ingroup preference. And you can change those assumptions and you can say like, "Well, suppose the whites and the blacks on your checkerboard have slightly different preferences and one of them has stronger ingroup preferences than the other." And you can mess around with it, and you'll get even sharper segregation.

0:28:13 WW: And I was thinking about that in the context of this massive glacial shift of populations from the country to the city. If there is even small differences, and this is what I think Schelling is telling you, it's like even if everybody's the same in terms of wanting to be near members of their ingroup, if there's differences in the nature of those groups, can make a big difference.

0:28:49 WW: So this is one of the... The first cut in my paper on, in terms of what predicts urbanization, is just ethnicity, right? So almost the entire non-white population has sorted itself into cities; it's... And that is explained largely by ingroup preference. Everybody likes to be around people like them, and especially if you are a minority who has, who is discriminated against, who has a history of oppression, you're gonna want some safety in numbers, and so you're gonna have to coordinate on a place to be. If you just scatter a minority around the territory of a country at random, they're gonna be isolated, and that's scary, right? So they tend to gravitate toward cities, pretty much any minority, and it doesn't have to be an ethnic minority; gays and lesbians are very, very heavily concentrated in cities and other kinds of minorities are as well. And there's a lot of reasons for that, but it's a clear thing that you see and it's not that African-Americans or Hispanics or Asians have more ingroup bias than anybody else, it's that they're the same on average. But in order to satisfy even a weak preference for being around people like them, they're all gonna have to basically go to the same place.

0:30:22 SC: Because there are fewer of them, yeah.

0:30:24 WW: That's the other few of them. There is no real option. If you're a person of color, you might prefer to live in a rural place, a low-density place, but there's no way to satisfy the preference of being around people like you and living in a rural place for the most part if you're an ethnic minority, so you have to give up on one of those two things. And most people who would have, whose residential preferences lean more in the direction of low density, if they're an ethnic minority, they just generally give up on living in the country and end up living in a slightly pastoral suburb or something like that, in a place that's close enough to other members of their group. But whites, the white majority in the United States has... It's easy; If you really like to live around other white people and you don't like urban density, you're in luck, 'cause you can live basically anywhere that's not a city is almost entirely white.

0:31:43 WW: And that is kind of the crux of a lot of the thinking in my paper where I'm just like, "So are there differences?" Because one of the things that then you're starting... So if you first pass as ethnicity, non-white ethnicity sort into city, some white people sort into cities, but others don't. And if you're trying to explain why the Republican party is the way it is, and the Republican party is almost entirely composed of white people who haven't sorted into cities, then there's an interesting question about if there are systematic differences between the white people who sorted into cities and the white people who didn't.

0:32:26 SC: But also before we get there, there is this issue of sorting in the sense of picking up and going somewhere versus just choosing not to leave, right? I mean, how many of the white people who are outside the city started inside a city and said, "Nope, this is not for me, I'm gonna move out to the country."

0:32:45 WW: You know, I don't know the number, but it's surpassingly small just given the overall trend of urbanization. So, just a huge percentage of moves are toward higher density, and that's one of the most important facts about urbanization, that means that almost all mobility is from lower to higher density, it's not always the case. There's been a big shift of populations within big urban areas where suburbs are gaining population faster than the denser cores and some of that is because housing prices and some part of what it means is that a lot of people... But there are a lot of people who are getting priced out of urban cores since are moving from higher density to slightly lower density suburbs, but those suburbs are still urban. And so there's not a lot of movement. So there is some movement from higher to lower density, but there's very, very little movement overall in the aggregate from metro areas to rural areas or from the city, from the core of a city to the fringe excerpts, you just don't see a lot of that.

0:34:08 WW: There are places like rural places that are gaining population, a lot of them are people who are from cities moving to the country, but they tend to be in the recreational rural category. So people who are buying a country home or you're moving to a ski resort or you love to hike and mountain bike and so you move out into the... To some nice spot outside Boulder or something like that. So there's some rural growth in those areas that involve people moving from cities to those places. But the overall trend...

0:34:46 WW: But very roughly speaking, yeah, we have sort of whites who want to be in the city moving to the city and minorities also moving to the city. And then whites who don't wanna be in the city just staying put where they are.

0:34:58 WW: Yeah, so there's a lot of staying put, but then there's also the trend of urbanization is so strong that still there's a lot of movement in any case. But where you stop is gonna reflect these differences among individuals that determine what kind of place they like to live in. So the incentive to urbanize is so strong that even people who are resistant to cities still, you're gonna earn more in the city, if you wanna capitalize on the wage bonus to higher education, it's hard to do if you don't move to a large labor market.

0:35:41 WW: So I live in Iowa most of the time, my wife is a professor at the University of Iowa and there's a lot of students here. I grew up in a smaller town in Iowa. And if you wanna, if you go to a public university and you get a bachelor's degree and you want to benefit economically from that training and that increase in your skills, you just can't go back to your... I can't go back to Marshalltown, Iowa and make what I make as a think tank vice President in Washington DC. I can't. I'm lucky that I can also live in Iowa city, Iowa. But the...

0:36:22 SC: Sorry, I think this is worth digging into a little bit also because I grew up in the '70s and the '80s, where cities were just thought of as vast oceans of poverty and crime. And it's still... Correct me if I'm wrong, but cities still have a lot of poverty in them, not just rural areas, but there are a lot more inequality in cities, there's very wealthy people, there's a healthy middle-class and there's poor people in cities. Whereas there's a little bit more homogeneity in the rural areas and it's homogeneity at an overall level of lower income than you might find in a city. Is that a fair, if rough...

0:36:58 WW: Oh yeah, absolutely. Cities have a massive amount of inequality, that's where poverty is very heavily concentrated and there are a lot of reasons for that. Ed Glaser has some great stuff on why cities are better for poor people and why they're particularly attractive if you have less money. But cities are increasingly productive as some of the podcasts that you've done are these efficiencies, increasing efficiencies from the population density, from agglomeration, as the economists call it and that is increasing the wage bonus to urbanization. So you've got these two things happening at once. You got a wage bonus from higher education, that's increasing because of technological change. As technology changes, it doesn't affect everybody's productivity equally.

0:38:00 WW: You need to have a higher and higher level of education to have your productivity amplified by the new communication and information technology. And we aren't educating people fast enough to keep up with demand. So there's a rising bonus to getting higher education, and to higher levels of education. And that is amplified by this independent, not independent, but related thing that's happening in cities where there's something about the knowledge economy and the information economy that Paul Romer, the Economist, is another noble prize winner who has done great work on how growth is increasingly a function of just coming up with new ideas.

0:38:53 WW: The ideas drive growth, and that idea production really seems to be higher when you concentrate a lot of really, really smart people together. You're a professor at one of the world's great universities, and it's kind of obvious when you're at a Caltech or something like that, that you're more productive there than you would be somewhere else, because you have all these incredibly smart people that you interact with every day, and that levels you up.

0:39:24 WW: I like to play pick-up basketball and you become a better basketball player if you play with better players, and that's just what it is for a large part. So there's two aspects of that increase in productivity from concentration is that if you're a coder, and you are around other great coders, you learn a lot from them and there's a kind of competitive pressure that pushes your level up. But that's not where most growth comes from, most growth doesn't come from just these marginal increases in individual productivity, it comes from these bigger ideas that lead to innovations that increase productivity in a way that scales across huge parts of the population. And so, those ideas tend to get produced more quickly when you get smart people together, kinda shooting the breeze. And so, there's an increasing concentration of economic production in cities and that makes them, as I say in the paper, more magnetic. Right? A good way to think about urbanization is that over time, cities... You know, cities are like magnets, and the incentives to urbanization are like the level of magnetic attraction. And it's like an electro-magnet, you keep turning it up, and the pull keeps getting stronger and stronger, and as that cluster of people gets bigger and bigger, it turns up the magnet, again, and again, and again. Which is why the whole population is filtering toward the cities. Unless you are not a very magnetic kind of person.

0:41:10 WW: As I say in the the paper, if you imagined it as ball bearings, just distributed on the table with a magnet in the middle, and the ball bearings are made out of all sorts of different metals, all the magnetic metals are gonna get drawn toward the magnet eventually. But if you're aluminum, or a plastic ball bearing or something, you're just gonna basically sit where you were the entire time. And I think there's something like that going on in the way urbanization has been working. Some of us are less magnetic than others, and so despite this very strong, just dynamic that's just happening, drawing millions and millions of people towards cities, some people are just less likely to filter in. And my conjecture, which I think there is some basis in, is that the things that make people less likely to urbanize are also things that predict more right-leaning political views.

0:42:19 SC: We're very fond of the physics-based analogies here on The Mindscape podcast, so we approve of that. But yeah, so that's what we wanna get into. Urbanization's a fact, and it affects the environment and it affects the knowledge economy and everything, but it also sorts, right? It doesn't affect everyone equally. And political leanings are one of those, but maybe... You also talk a lot about personality types and the Big Five. And is it maybe causally, that comes before the political leaning?

0:42:48 WW: Yeah, I think so. There's controversy about the extent to which personality is a independent variable, the extent to which is exogenous of people's political opinions. So the question is, maybe does moving to a city make you a more liberal personality type? Does living in the country make you more conservative? And...

0:43:20 SC: Or education, right?

0:43:22 WW: Or education. So the trait among the big five that are most politically relevant, are openness to experience and conscientiousness. These predict whether you're more liberal or conservative in your social views. That's...

0:43:38 SC: Tell us what all five of them are, 'cause we might not know.

0:43:42 WW: A good mnemonic is OCEAN; Openness to experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Neuroticism 's often called emotional stability if you kind of flip the sign of it. Most of those have no relationship to political views. But openness and conscientiousness have pretty significant relationships.

0:44:14 SC: Do you wanna guess what my results were?

0:44:16 WW: You are... So, all academics are relatively high openness.

0:44:22 SC: Yeah, super open, yeah.

0:44:24 WW: You're high openness, you've got a podcast about discussing ideas.

0:44:27 SC: I know.

0:44:30 WW: That illustrates what openness is. So openness is, curiosity is a large part of it, it involves just interest in new things. So if you're high in openness, you're more interested in reading the new novel, you're interested in the cool new movie, you're interested in traveling to places you haven't been before and encountering other cultures, encountering people who aren't like you, you're interested in trying new cuisines, things like that. And that correlates, that's the strongest correlate of liberalism or conservative. Or high openness people tend to be more liberal, lower openness people tend to be more conservative. The other trait that has a significant relationship is conscientiousness. And conscientiousness is the getting it done personality trait. You know, highly conscientious people keep lists, meet deadlines, they just generally have their shit together. That's what conscientiousness is. So it might not be clear how that relates politically. High conscientious people tend to be more conservative, low conscientious people tend to be more liberal. The conservatism of conscientiousness is involved in... One thing that conscientious people really dislike is uncertainty. There's a strong... Conscientious people want there to be a clear relationship between effort and reward, or inputs and outputs. It's the A student personality trait. It's Hermione Granger. You wanna know what you need to do to get the thing.

0:46:34 SC: Yeah.

0:46:34 WW: And so, what do I have to do to get the grade? So, your conscientious students are the ones who badger you after class about what exactly the syllabus means, because they gotta know.

0:46:43 SC: Wanting the world to be just.

0:46:46 WW: Yeah, yeah. And, the low conscientiousness people like me, [chuckle] who don't keep lists and... Just, are amazed if they ever make a deadline, are much more tolerant of this kind of uncertainty and inflexibility. And so, there's an inflexibility in conscientiousness, and there tends be a slight fear of just, a strong desire for stability. They just wanna know how everything works, so they can hit their marks.

0:47:27 SC: I was very low on neuroticism, and completely middle-of-the-road on conscientiousness, extraversion and agreeableness. But, it's interesting to me, this, both conservatives and liberals get one good quality that they correlate strongly with, right? 'Cause, most people would probably say, being conscientious is good, being open is good. That's the normal valance that those terms have.

0:47:49 WW: Yeah.

0:47:50 SC: But, is there... I take it that, because they're supposed to be useful dimensions, in five-dimensional personality space, there must be people who are high conscientiousness and high openness, and low in each, right? And, they don't have an obvious place to fit.

0:48:05 WW: Absolutely. Yeah, like, the way these traits emerge, it's not exactly that they're real things, but the traits come out of a factor analysis where, you're trying to figure out the minimal set of traits that don't correlate very strongly with one another, right? So, the whole idea is that they're independent of each other. And so, higher openness and conscientious just swing completely freely of one another. The academic personality type is very high openness, relatively high conscientiousness, like academics tend to be A students, right?

0:48:42 SC: Yeah.

0:48:44 WW: It's hard to become a professor, to get through that much school, if you can't turn papers in on time.

0:48:50 SC: Right.

0:48:52 WW: And, low conscientiousness people struggle with that. But, conscientiousness is the best trait to have, in terms of predicting success in school and in your career. So, higher conscientiousness people are more likely to finish school. They're more likely to finish anything, if they start it. And, high conscientiousness predicts higher salaries. People... Highly conscientious people tend to be a little more productive. Conscientiousness doesn't make you wanna do anything, it's a kind of, auxiliary, or kind of workhorse trait, but openness has more motivational drive to it. So, if you're high openness, it makes you attracted to certain kinds of things. So, conscientiousness is the trait that makes you good at school, openness is the trait that makes you want to learn.

0:49:47 SC: Right.

0:49:51 WW: And, those are relatively independent of one another. There's a sad finding that I reported in the paper, from Shelly Lundberg, labor economist at Santa Barbara, I think. And... Which is the that, generally, conscientiousness predicts academic performance, but it actually doesn't for lower socioeconomic status students. You'd wanna think that the working hard and getting stuff done dimension, would predict academic success for less wealthy black students, for example. But, it doesn't. But, it turns out that openness does, right? And, I think, that's a good example, where you seeing the motivational aspect of openness, that if somebody's less privileged, and the deck is stacked against them, the thing that really pulls you through, is just the desire to learn.

0:50:55 SC: Interesting, yeah.

0:50:58 WW: And so, these traits, they're interesting. And, one of the things... One of the reasons why I fixed on the big five, is 'cause, there are other personality theories that are specifically intended to explain political views, and moral views. Like, Jonathan Haidt's Moral Foundations Theory. But, some of those are a little bit problematic. It's hard to... Sometimes the... It's not so clear that the... That if I identify as a conservative, that that doesn't just affect my answers on the...

0:51:36 SC: Yeah.

0:51:37 WW: The moral foundations quiz. But, the big five isn't intended to explain your politics, and it explains lots of other things, and has been... Replicates really, really well, and helps explain all manner of behavior. And, that's one of the things that I found interesting about it, because high openness explains... Weakly predicts your inclination to go to college, at all...

0:52:06 SC: Mm-hmm.

0:52:07 WW: Even though, it doesn't mean that you'll be good at it, it makes you wanna go to school. And, if you go to school, and get a college degree, that amps up your magnetic attraction to cities, because that's where you're gonna benefit from your degree. But, more...

0:52:28 SC: And presumably, even if not, right? The idea that, if you did grow up in a rural environment, the chances that you would pick up stakes and move to a scary, diverse, pluralistic, urban environment are probably much greater, if you score high on openness.

0:52:43 WW: Yeah, absolutely. And, that's one of the most important aspects of the set of correlations that openness and conscientiousness have with other stuff. So, both openness and... Low openness and high conscientiousness relate to a broad set of traits that you can just call ethnocentrism, or in-group bias. And so, people who are lower openness tend to be more ethnocentric, their degree of homophily, the strength of their preferences for sameness, are stronger. And so, lower openness people are more put off by difference and diversity. And so, if you're lower openness that's gonna make you less interested in, and maybe averse to, places where there are a lot of people who are unlike you. And, that's very, very interesting, and especially since, in the context of a... Of someone like Donald Trump, who's doing everything he can to elicit people's sense of ethnocentric solidarity. So, higher openness people, as I said before, are interested in people who aren't like them, they're interested in other cultures, they're interested in other foods. So, if you're higher in openness, you're just gonna find the urban diversity more attractive. And, if you're low in openness, you're gonna find it unsettling. So, that's important just in and of itself. But then, secondarily... And, this is one of the things that I found most interesting is that, lower openness also just predicts your inclination to migrate, at all.

0:54:44 SC: Yeah.

0:54:45 WW: So, higher openness people... And, it makes sense, when you start thinking about the... How it relates to an interest in novelty and difference. Lower openness people are less likely to want to move, and they're less likely to actually move. Higher openness people are way more likely to wanna go somewhere new. Which is one of the reasons why higher openness people are somewhat... I wanna be careful about not making it sound like openness is great, and low openness is terrible.

0:55:19 SC: Right.

0:55:20 WW: Because, lower openness people are just better friends. [chuckle] They...

0:55:24 SC: They stick with their group.

0:55:26 WW: They stick to their group, right. Your low openness friend is the guy who's gonna show up at three in the morning and bail you out of jail.

0:55:34 SC: Yeah.

0:55:34 WW: Right? Like, if you... Your lowest openness kid is the one who's gonna call you when you're old.

0:55:40 SC: Yeah, be there for you. Sure, right. Yeah.

0:55:43 WW: Your...

0:55:43 SC: I have two anecdotes... I know, this is not really systematic data, but it helps make all these points vivid to me. One was, driving someone around, an older person who I'm sure would score in low openness, driving around my neighborhood here in LA and seeing all of these signs on the storefronts, many which are in Spanish, some of which are in Asian languages, and they just said, "Doesn't that bother you?" And, I'm like, "No, the food is much better here, because of all this kind of diversity we have." But, it just struck me that I wouldn't even have thought that that should bother me.

0:56:19 SC: And, on the other side of the valence side, I knew a guy who had been in the Army his whole life, and he retired, and he immediately got a job as a security guard, and explaining why, he mentioned the fact that he got to wear a uniform every day. And again, that never would have occurred to me as a good thing, but I get it, that it is a good thing. And, I kind of don't like the label openness, for that reason. It sort of biases us towards instantly thinking that openness is good, but there are absolutely values. I think that having different restaurants with different ethnicities is an unambiguous good thing, but I get the idea that there are people who just want to keep things simple, uniform, doing the same thing every day, so they have space to worry about other things, that's not intrinsically a personal failing.

0:57:12 WW: No, not at all. And, that is... And, I think... So, if my overall hypothesis is right, in that over time, the higher openness people are more likely to migrate, and therefore urbanize, because migration is mostly urbanizing migration, and lower openness people are gonna be more resistant to... Or, less sensitive to the incentives that drive people to urbanize. Over time, the less dense populations, the rural populations, should become lower and lower openness. Like, that is an implication of the view. And, as the magnetism of cities ramps up, it will tend to pick people off who are on the margin. Each of these traits is normally distributed, and so people who are on the low tail of openness are least likely... Most likely to be rooted, to put down stakes, to be incredibly loyal to their community, to family, to the people around them, they're not gonna wanna give up on that. But, most people are in the middle, by definition. And, as you move down the bell curve, as the magnetism of the city ramps up, it starts picking people off further and further down the bell curve. But, that leaves the average in a lot of these places, in higher open... Like, lower openness.

0:58:52 SC: It shifts, yeah. Right.

0:58:53 WW: And, that will tend to give an increasingly conservative, ethnocentric cast to a lot of these places. I wanted to mention that openness and conscientiousness predict your... Predict social and liberal... I'm sorry, social liberalism and social conservatism. Things like abortion, same-sex marriage, immigration, attitudes towards race, but it doesn't relate at all to economic views. That doesn't... Those don't relate in any systematic way, to any of the personality stuff. So, it's just these social views. So, if over time, the sorting dynamic of urbanization is leaving these places increasingly low in openness, they're also getting higher in ethnocentrism.

0:59:50 WW: And then, on top of that, you have the effects of the thing that's driving people to the city in the first place, which is that, that is where economic production increasingly happens. So, I draw heavily in the paper on work by Enrico Moretti, who's got... Talks about the great divergence, that there is this real divergence in our economy between a handful of extremely high productivity cities, and everywhere else. Everywhere else includes a bunch of other cities, including Rust Belt cities that are in decline. Though, it's not that all the places that are in relative decline, are not urban. But, almost all the places that are on the upswing, are urban. And, almost the entire lower density parts of the country are either, stagnating economically or actually declining, in terms of economic welfare. And so, when you add an increasingly low openness, high ethnocentric white population to this economic stagnation, you're gonna get a lot of disgruntlement.

1:01:11 SC: [chuckle] Yeah.

1:01:13 WW: And, those populations, as well, are... The average level of education is going down. Again, because of the overall magnetism of cities, to highly skilled, highly educated people. And, that is basically the reason why... That's the first order explanation for the great divergence, that the increasing wage bonus to higher education, and the concentration of all the jobs where you get that wage bonus in big cities, has filtered almost the entire highly educated population out of the rest of the country. And, that leaves these other places at a permanently kinda, lower level of productivity.

1:02:03 SC: I did wanna ask an economics question here. I've seen various graphs that seem pretty convincing, that after the 2008 recession, there was a comeback, but the comeback went very strongly to people who were doing well in the first place. Like, the rich people are doing fine after 2008, the middle class is doing okay, and almost none of the gains went to people who were doing badly. Is there substructure there, in terms of rural versus urban? Did urban poor people come back more than rural ones, or vice versa?

1:02:38 WW: I'm not sure about the poor population, specifically. But, urban populations bounce back much, much, much quicker than rural populations. And, that is a big part of the story, that those places don't do well with... Here's an interesting, like a little sidebar, conscientiousness, as I said, is the individual trait that most predicts just, success in your career. And, conscientiousness also... Conscientiousness doesn't make you less likely to migrate. But, if you are... But, it makes you more resolute in executing any preferences that you might actually have. And so, if you're the most conservative profile, if you're low openness and high conscientiousness, you're gonna really stick to not going anywhere. And so, higher conscientiousness at the individual level means that you're gonna have a higher income.

1:03:52 WW: But, higher conscientiousness at the population level doesn't predict a higher level of productivity. And, I think, that has to do with the fact that growth is an ideas thing, and that it's also has to do with flexibility. So, there's a great paper about the UK, in terms of population level, personality traits, and the higher conscientiousness places didn't bounce back from the recession as fast as the higher openness places. And, that seems to be because higher openness people are more flexible, they like to, "How are we gonna deal with this problem?" The high conscientiousness people are the ones who wanna know what the rules are, but if the rules change, they struggle.

1:04:47 SC: And so, high conscientiousness people can take advantage of opportunities, but high openness people are more likely to get the opportunities, or go out and actively get them.

1:04:55 WW: Yeah. And, they're also... They're gonna be the kind of people who explore the space of possibility, and see how to adapt to the new situation. So, it's the creative personality type. The most creative profile is mine, as it happens, like very high openness, very low conscientiousness, that is associative and flexible. But, high conscientiousness, low openness is very... You just wanna do the done thing, and if the world changes around you, it's just incredibly confusing. And, I think, it's super important not to be judgmental about that.

1:05:40 SC: Sure.

1:05:41 WW: That's just how... One of the things that writing this paper has done for me is, it's actually made me feel more empathetic toward Trump voters, to try to get inside what the mindset is of lower openness, higher conscientiousness people. The changes that our culture, economy, population is going through are truly unsettling, if you have that kind of mindset. This is a high openness thing, trying to get inside somebody else's head, but...

1:06:18 SC: The paradox of openness.

1:06:20 WW: Yeah, paradox of openness. But, that's partly why higher openness people are more... Have higher racial sympathy, for example. They're more likely to be able to understand what it might mean to be a minority and have opportunities systematically denied to you in these kind of structural ways. Whereas, low openness people just don't get it, they have a hard time understanding what other people's experience is like.

1:06:54 SC: Well, just to make this.

1:06:55 WW: 'Cause, they're not really interested.

1:06:55 SC: Yeah, and just to make this very clear, I think, that the picture that you're painting seems to come together in a view where there's a set of people who live outside the cities, who have been legitimately, really damaged by the economy, and at the same time... And, maybe for related reasons, are ones who are naturally prone to be a little bit more skeptical of minorities, and change, and foreigners, and immigrants, and things like that. And, it comes together, and maybe this argument we had over why Trump won, after he won, was it because of economic anxiety, or because of racism, or nationalism? These things are all different aspects of the same underlying causation.

1:07:44 WW: Exactly. And, that's one of the things that I try to draw out, that they're not really two separate explanations. There's this big macro-economic fact, which urbanization really is. It has to do with the changing structure of the economy, and the incentives that that gives people to resettle. And, that has these strong effects on who gets the benefits of economic growth. If this dynamic is filtering the population in a way that leaves lower density populations, basically, increasingly socially conservative, but also depriving them of the benefits of growth. It's not happening where they live, and they're not getting the full benefit of it, that puts those people in a position where it becomes very easy to sell them a narrative about why things seem so bad to them. So, if somebody like Trump comes along and says, "Things are going shitty for you. I'm gonna make America great again, which means make America like it was when you felt comfortable."

1:09:02 SC: Or like you thought it was when you felt comfortable. Yes.

1:09:04 WW: Yeah, exactly. Your sort of nostalgic fantasy about what the past was like. And the thing that's causing all these problems, is all these immigrants and these elites who live in cities who are selling you out to the Chinese and giving your jobs to Mexicans, and so on, and so forth. The kind of person who lives in those places is going to be very prone to find that really persuasive. And then the additional factor that I lay onto it... So most of this explanation is, and the overall story I'm telling, is about selection effects. And some selection effects that have been, I think overlooked, in the way that urbanization has segregated the population in this sort of Schelling-like way. But there are these treatment effects, right? There's this large literature on how growth tends to be liberalizing.

1:10:09 WW: That the further you get from a sense of economic insecurity, basically the more tolerant and open you are to difference and change, and this is really, really well confirmed. It feels, to a lot of us, like there's a one-way arrow to moral progress that's in a liberalizing direction because economic prosperity, or rising economic prosperity, tends to make whole populations more culturally liberal. You get a transition from Ronald Inglehart, is the big innovator in this area from what he calls survival values to self-expression values. But you don't get that in a uniform way over an entire population when growth is increasingly economically concentrated in cities. So, all of the already more liberal people in cities are experiencing the benefits of growth, which tends to make those populations even more liberal, right?

1:11:23 WW: A good example of that is the change in, you know, even the past few years, towards transgender people and the norms around it. Right? So that rapid shift in norms about acceptance of transgender people, how important it is to use people's preferred pronouns to acknowledge their preferred gender identity, that's textbook increase in self-expression values. But the kind of growth that makes people have increasing self-expression values, that's not going to these already more conservative lower openness populations, then you're getting even further polarization in terms of culture and values. So, to that population who's not experiencing the same increase in prosperity, and they're already more conservative, they hear talk about using somebody's preferred pronoun, and they're like, "What the hell is even happening?"

1:12:29 WW: There are two... I get emails from all of these conservative institutions, and they're just all going crazy right now about how we can't tell the difference between a man and a woman. And I think that is a really direct effect of the joint filtering of the population, leaving the rural populations more conservative in terms of disposition, but also depriving them of the kind of treatment effects of growth that would make them a little bit more liberal intolerant. They're just not getting it. And so the urban rural cultures, moral cultures and political cultures, are just growing further and further apart, and to the extent that there's a kind of backlash. I think it's driven by those combined effects, where it just seems literally crazy to conservative people, conservative white people in small towns, to hear people talking about... About, you just like choose your own gender. It just seems absolutely, it seems like the whole world's upside down. But for us...

1:13:36 SC: And so, what is the... We haven't quite yet talked about the role of education here 'cause I think this is like the final piece of the puzzle that you talk about in the paper. We have this side of people, rural people, low on openness, things are changing all around them, they've been left behind by the economy, those populations are, people in families from those regions might have their perspective shifted if they got more education... But I never know what the causality is? Is it just the people who are more open in the first place tend to go to college or people who go to college become a little more open?

1:14:12 WW: It's very clearly both. So the personality stuff is it's not fixed. The openness say is about the heritability goes at about 60%, the variation that's explained by genes is about that. But there's still that leaves a lot of room for change, for differences that are environmentally determined, and it's very clear that getting a college degree makes you more open, traveling when you're young makes you more open. So going to college would increase openness and does increase social liberalism. But it's also the case that if you're already more open, you're more likely to wanna go to college. And I think one thing that people have overlooked which is clear to me having grown up in Iowa and living in Iowa city where there are a bunch of students from rural areas, people overlook especially high openness urban people tend to overlook the extent to which going to college is a form of migration that is uncomfortable to really rooted socially, temperamentally, socially conservative types. Going to college means moving away from your family. It means moving away from your friends. And there's a huge attrition rate from freshman [laughter] not coming back for their sophomore year and I think and some of it is just like it's a bad fit.

1:15:49 WW: And if you're from a small Iowa rural town and you come to the University of Iowa, it's way more diverse than any place you've ever been. It does, it seems like a wild big city to you and if those rural populations are becoming more conservative over time, I think their parents are, find it less attractive to send their kids as well. Like it is true that sending your kid to college is gonna make them a little bit more liberal, but, like, it also means sending them away from you, you don't wanna do that, like you love them. You don't want them to go away and you especially don't want them to go away to a place that's gonna make them even more different from you and that if they get a college degree, they're gonna have to move even further away from you and to this really scary big city that is dangerous and full of weird languages and smells, and food. Like it's unappealing. And, so I think some of the right-wing reaction against universities currently has to do with some of this just very deep seated discomfort in... There's a feeling that somehow it's like left-wing propaganda that is making their children different from them [chuckle], but I think that's a kind of rationalization and the deeper thing is...

1:17:15 SC: But also...

1:17:16 WW: Not wanting to be separated from your loved ones.

1:17:18 SC: Yeah, and which I was gonna say that's totally understandable in some way. We do live in a society where the idea that families live together in the same neighborhood over generations is more or less disappearing in most of our population.

1:17:34 WW: Yeah, absolutely and that's a real loss.

1:17:39 SC: Yep.

1:17:41 WW: There's a real loss of rootedness. These lower openness places tend to be higher, be in a social capital kinds of places like when people stick around, they know each other better, they tend to be more deeply invested in churches, in the Lions Club and the Rotary, and all of these civil society institutions, those places have a rich informal, really tightly woven together social life which is, has a lot of advantages. It's a really nice way to live if you fit that kind of place, like it's suffocating for a certain kind of person. But everybody doesn't have to live the same kind of life, but that kind of life is becoming less and less feasible, it's becoming less economically feasible and it feels if you've lived in one of those places, it feels like the world is trying to destroy everything that's important to you and it's worth taking that seriously.

1:18:53 SC: Yeah, you briefly mentioned churches but you didn't talk about religion a lot in the paper, is there... There's this even be above urbanization there is just the whole idea of modernization. And the strong attachments we have to community, to family, to churches are weakening with time, and probably the increasing secularization of the country in the world is something that is both significant and very bothersome to the low openness people who are out there in the rural districts.

1:19:25 WW: Yeah, absolutely. The secularization is one of those things that... It tends to go along with rising self-expression values, so religious participation tends to fall as GDP per capita increases, as people get more and more wealthy. What self-expression values mean is that what tends to dominate your interest is being myself, finding the thing that fits, and consumer culture is really play into that. And that's not really what the idea of religion is; it's...

1:20:11 SC: Yeah, usually.

1:20:14 WW: Yeah, so people who are high in self-expression values are gonna be really annoyed that the Catholic church won't change its views on birth control or on same-sex marriage; you're like, "Get with it folks." But that's not what religions are for. One of the interesting things about the United States is, one of the reasons it, I think, maintains a higher level of religious participation than a lot of European countries is that it has this history of really entrepreneurial religious activity. When I, I lived in Houston for a couple of years, and there's this guy... What's his name? Joel Osteen... He's a big TV pastor, and he's got the old basketball stadium as his church; it fits 15000 people. And I went to it a couple of times; I'm just fascinated by it. Again, another high openness thing. I wanna see what the low openness people do, right?

1:21:11 SC: Yeah.

1:21:11 WW: And it's barely a religion; like he said, "Jesus twice." It's just this prosperity gospel stuff, but it's all... And so it's really heavily customized to what a certain kind of person wants to hear, and that keeps people coming to church. It's about how if you have faith and try to look good, like you buy a car that's nicer than you can afford and then God will help you afford it. You know, that's kinda...

1:21:43 SC: Positive feedback, yeah.

1:21:45 WW: And so... But that keeps people going to church; it's adaptive in a way that Catholicism isn't. But it also just rinses the actual religious content out of it, and I think that has a lot to do with Evangelical support for Trump. It's a certain kind of person, but the actual content of their religious convictions is... Evangelicalism is basically Americanism with a light Christian gloss on it, and it doesn't really... It's more political than it is religious; it's more about being against abortion and being in favor of American exceptionalism than it really is about exemplifying the lessons of Christ in your personal life activity. That's not just... And I don't wanna paint with too broad a brush; there are deeply devoted evangelicals who spend all their time helping people in need, but there's also just a very vulgar self-expressive version of it that isn't really about anything other than the expression of a suite of right-leaning views of the world.

1:23:15 SC: Well, it can seem very weird, bizarre to outsiders that people whose self-identity is so centered around their Christianity and religiosity are fervent supporters of Donald Trump for a whole bunch of different reasons, but... So maybe the diagnosis is on the table; I wanna sort of move on to prescriptions in a couple ways, unless you think that we've missed anything that you wanted to say about the overall picture you're painting.

1:23:42 WW: No, no, I think we got most of it in.

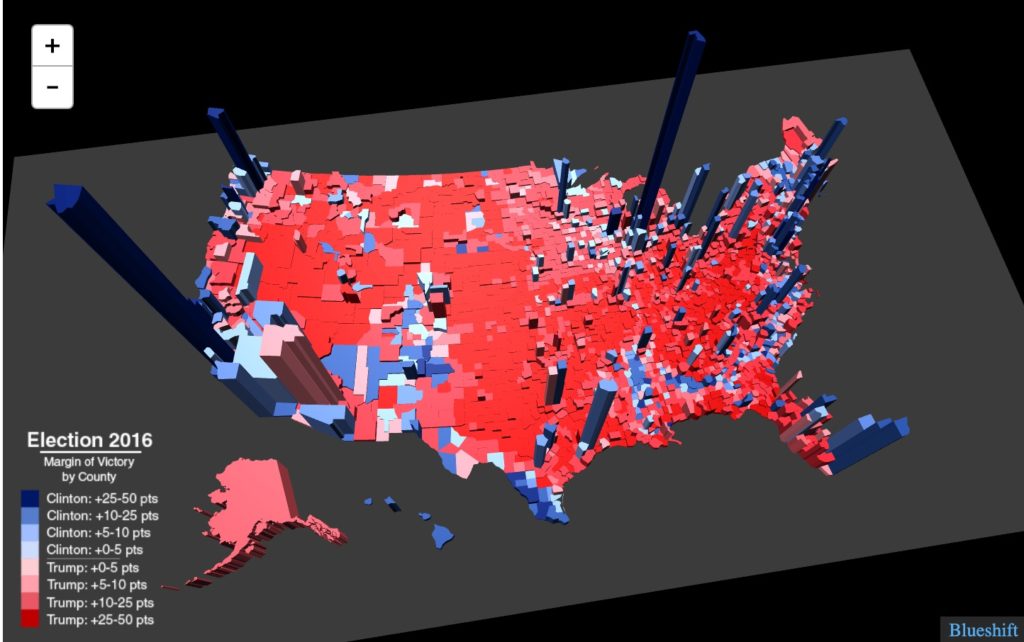

1:23:45 SC: Yeah, I think that there's two big things looming in my mind here. One is, you make the point that people like to do these maps of the United States and who voted red and who voted blue, and especially if you do it at the county level, the blue counties are very, very tiny, and in a sense that's because you're just painting by acreage, right?

1:24:07 WW: Mm-hmm.

1:24:07 SC: Yes, it's absolutely true that most of the acres, most of the land area in the United States voted for Donald Trump, but most of the people voted for Hillary Clinton, and they also, most of the people voted for Democratic Senate candidates, but they didn't win. And you make the extra point that a vast majority of the GDP voted for Hillary Clinton, right?

1:24:27 WW: Excellent.

1:24:27 SC: There's much greater economic productivity in the blue regions than there are in the red ones. But furthermore, the trends are all in the direction of increasing representation for those blue areas in various reasons. So it paints a picture where the Republican Party, forget about conservative versus liberal as ideological designations, but as an institution, the Republican Party is taking advantage of certain, not really democratic features of our Republican government, the Senate, the Supreme Court, the Electoral College, but that can't go on forever. And are we facing at some point a tipping point, as we started talking in the conversation about, a tipping point where the Republican party just collapses and it gets 30% of the vote share and is in the wilderness for 15-20 years?

1:25:24 WW: We think a lot about that at the Niskanen Center, 'cause one of our big projects is trying to restore a moderate elements to the Republican Party, the more the kinda Rockefeller Republican type of moderation. And it does seem extremely unstable, but it's, but I think we're at a really dangerous moment as well. So as you said, it's the... A lot of people didn't know about the, after the 2012 election, the GOP did this analysis about what we need to do to win, and their overall consensus was that we need to just increase non-white vote share, and if we can do that, we can hang on with big national majorities indefinitely. There was a lot of talk about how George W. Bush got like 42% of the Hispanic vote.

1:26:28 WW: If the Republican Party can do that consistently they're golden because there is this baked in low-density bias in our entire electoral system. So if we have what I'm calling the density divide in the less dense part of the density divide is systematically advantaged by the overall electoral structure of our system. Then they can win, they don't need majorities to win, they just need to keep just chipping away at democratic non-white vote share, or even just by one or two points every cycle, and they can just win forever, right? Now that was the idea. And the whole party apparatus, bought into that, and that's why in the last election, Rubio Cruz, all these guys were in favor of comprehensive immigration reform that was part of this pivot, but that's out of sync with where the Republican electoral base is, and there was a $20 bill laying on the ground that Trump picked up that this increasingly ethnocentric lower density population who's experiencing economic stagnation kind of cultural vertigo like they don't want more immigration and so he just doubled down on this kind of nativism which has shrunk the GOP's electoral base. So now it's almost exclusively white, it's almost exclusively exurban and rural, and they can't keep winning with that coalition.

1:28:25 WW: So they've got two options, which is either to do what they were gonna do in 2012 and start chipping into the Democrat's advantage with non-white voters, or they can cheat basically, and it looks for all the world there's a very strong investment in cheating.

1:28:52 SC: In cheating. Yeah.

1:28:52 WW: And that is super dangerous and it's very, very bad news. So everybody knows about the Russian interference in the election, everybody knows about how the GOP is doing nothing about securing our elections at all, how the Supreme Court has said that pretty radical partisan gerrymandering is okay. And so, the GOP right now seems to be just doubling down on winning elections, with a shrinking minority by disenfranchising Democratic voters, and just straight up cheating, and that really threatens the legitimacy of our democratic system in a way that could be really destabilizing.

1:29:54 SC: Yeah, and I do think that... Well, we actually didn't talk as much as I wanted to about what I think as the paradox of racism here in the sense that it seems weird at face value, to say that it was increasing racism that caused the white Democratic candidate in 2016 to lose even though the black democratic candidate won in 2004 and 2008. Or sorry, 2008-2012. I mean, why would increasing racism have more an effect when both of the candidates were white? But there is... I think that there is an explanation there, maybe we could tease that out a little bit.

1:30:39 WW: One of the... Getting into more political alignment side, one thing that's been happening over the past 30 years, part of this overall sorting story is that the parties have just become better sorted on a bunch of stuff. And there used to be a lot of liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats and that's changed. There are very few of them anymore, so all the conservatives have gone into the Republic Party all the liberals have gone into the Democratic Party. But one thing that's... It's really hard to get across to highly educated people who follow politics closely. It's just how little most people pay any attention to politics, at all, and how...

1:31:24 SC: Absolutely, yeah.

1:31:24 WW: How little people know. And so, party alignment is, first of all. Nobody lays out all their views. Here's my view on the minimum wage. Here's my view on abortion. Here's my view on blah, blah, blah. And then... Oh, let me... And then let me check which party matches that better. That's 100% not how it works. How it works is, first you... It's what social identity is most salient to you, and that's more complicated for white people because, being in the majority, just being white isn't so distinctive. But it's pretty clear for other groups. Right? Like, "I'm black, I wanna vote for the party that's gonna protect me against discrimination." Right? And so you learn that that's the Democrats and then you're a Democrat, and then once you're a Democrat, then you adopt Democratic us about things. Same on the other side. Right? So it's come to be that if you're a certain kind of white person, you're a Democrat, and if you're a certain kind of white person, you're Republican. But people pay so little attention... And this is what I've found one of most depressing findings, is that a big part of the flight of working class whites toward the Republican party really does seem to have been caused by Barack Obama being President.

1:32:50 SC: Just existing, yeah.

1:32:51 WW: Just existing. A black Democrat in the White House was a clear enough signal for people who don't generally tune in to communicate that, "Oh, Democrats are the party for black people who are for civil rights. Oh, I'm not for that." And so there was a huge shift in whites with lower levels of education toward the Republican party that really does seem to have been generated simply by the fact of... The clarity of the cue that Obama's blackness sent.

1:33:31 SC: But that doesn't seem to explain people who shifted from being Obama voters to being Trump voters.

1:33:38 WW: That's interesting. It doesn't, but I think there is... You see that shift. The interesting thing is you see that shift happening well before Trump. And so it was happening anyway, largely sparked by just reaction to Obama's race. And then you have Trump eliciting these ethnocentric impulses that are more common in that population. So part of the sorting story also involves de-unionization. So the close connection between organized labor and the Democratic party locked a lot of working class people into the Democratic party, kind of reflexively, it's just part of their identity. I'm a member of the FLCIO, so I vote democratic. But falling union participation, just falling rates of union membership, have weakened those ties. Party loyalty is kinda sticky over generations.

1:34:48 WW: Just the fact that your parents are Republican makes you way more likely to be Republican. And if your dad was a steel worker who was a staunch union guy and Democratic voter, you're likely to identify that way too, but those... But if you're not a member of the union and that culture is just fading away where you live, those connections become more and more tenuous, and then those people tend to start sorting more on these other identities. "I'm a white person. I don't like urban liberals. I don't like uppity black people in the White House like President Obama." And that kind of person, if a guy like Trump comes along and activates, really encourages any ethnocentric impulse that you might have, I think that can instigate a further shift. But I think it was happening before him, he just heightened the dynamic.