If you’re bad, we are taught, you go to Hell. Who in the world came up with that idea? Some will answer God, but for the purpose of today’s podcast discussion we’ll put that possibility aside and look into the human origins and history of the idea of the Bad Place. Marq de Villiers is a writer and journalist who has authored a series of non-fiction books, many on science and the environment. In Hell & Damnation, he takes a detour to examine the manifold ways in which societies have imagined the afterlife. The idea of eternal punishment is widespread, but not quite universal; we might learn something about ourselves by asking where it came from.

Support Mindscape on Patreon or Paypal.

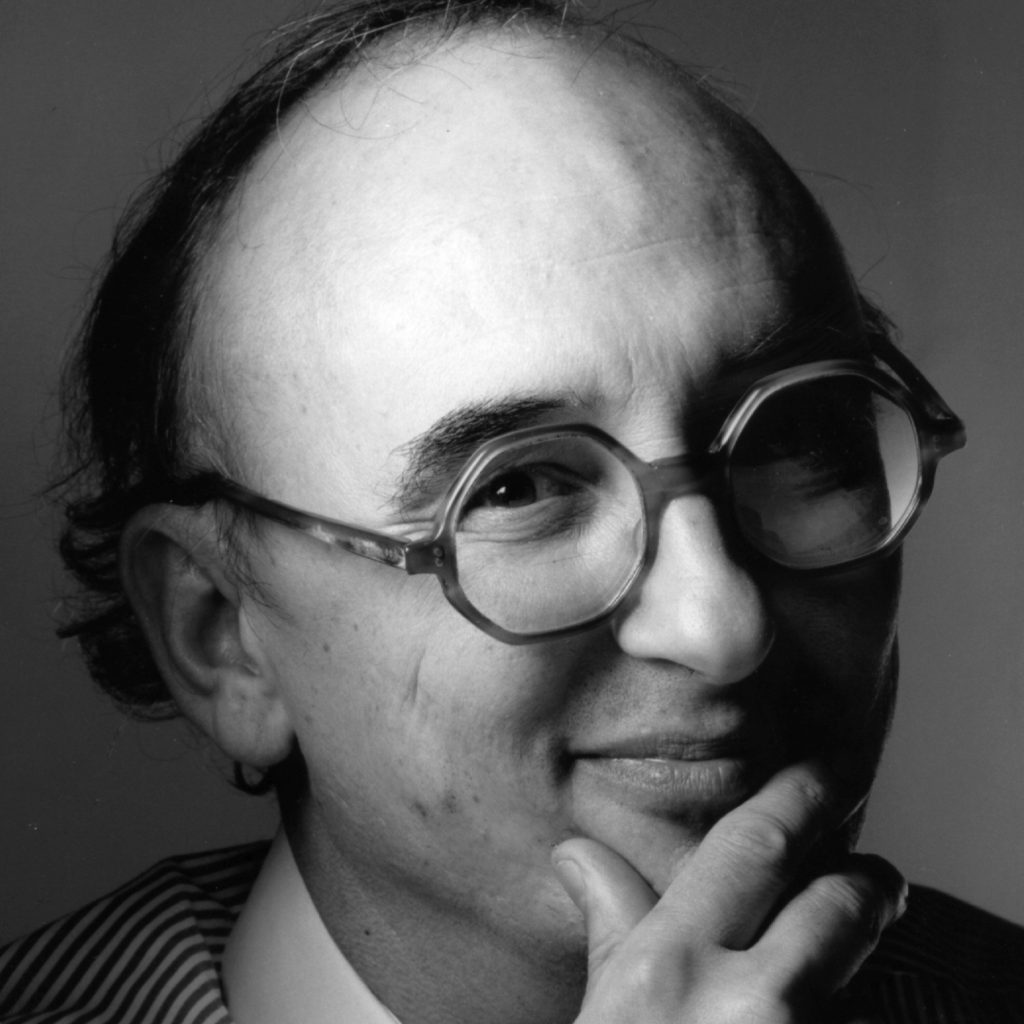

Marq de Villiers was born in South Africa and now lives in Canada. He has worked as a reporter in a number of locations, from Cape Town to London to Moscow to Toronto. His books cover a variety of topics, including a number on history and ecology. He has been named a Member of the Order of Canada and awarded an honorary degree from Dalhousie University, among other accolades.

[accordion clicktoclose=”true”][accordion-item tag=”p” state=closed title=”Click to Show Episode Transcript”]Click above to close.

0:00:00 Sean Carroll: Hello everyone, and welcome to “The Mindscape Podcast,” I’m your host, Sean Carroll, and today we are going to hell. I’m sure that some listeners or at least some people who know about the podcast, have long been convinced that I personally am going to hell. But today we’ll take a slightly more academic or at least scholarly look at the idea of what hell is, where it came from, why it came to be, what’s supposed to be going on there, what people think about it right now. Today’s guest, Marc de Villiers is a Canadian writer, he’s written non-fiction books about many different things. About history, about politics, about the environment, about ecology; and for whatever reason, he decided to become interested in the idea of hell. Now, let me be very, very clear, ’cause I know we have a broad audience, this is a conversation between two people who are completely convinced that hell is not real, okay? We’re not actually sitting down and wondering whether or not hell might really exist. We both, kind of take for granted that it doesn’t. And I know that not everyone agrees with that, so apologies if we’re not speaking to you about this issue.

0:01:04 SC: But from this point of view of someone who doesn’t believe in hell, the fact that so many people do is fascinating, right? Why did we invent this? What was it about human nature, that made us think that there should be a place where you went to, to suffer eternal torment if you were bad? That’s a very, very dramatic kind of thing, and it’s not as if even in the modern world, belief in hell is restricted to 2% of extremist people. Most people in the United States believe that hell is real. Most religions, whether it’s not just Christianity, but also, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, most religions in one form or another, has something we would recognize as hell. For that matter, polytheistic religions, pagan religions, long before monotheistic religion came on the scene, had this kind of idea. So what brought that about, what does it tell us about human beings?

0:02:00 SC: And of course, it’s fun to think about the psychology, the history, the sociology, but there’s also a lot of wonderful little details, anecdotes, stories. Because hell is a great place to place a story? As we mentioned in the podcast Dante’s Inferno is a much more compelling and popular story than Dante’s Paradiso is. Hell is just kind of a more interesting compelling place than heaven is, even if you wanna go to heaven, and not to hell. Alright, so we’re gonna learn a lot about that. I learned a lot from this, as much as I’m not personally religious, the history of religious thought I think is both fascinating and important, because it really does tell us something about human beings and how they perceive of their own place in the wider cosmos, so let’s go.

[music]

0:03:01 SC: Marq de Villiers welcome to The “Mindscape podcast”.

0:03:04 Marq De Villiers: Well, thank you for inviting me.

0:03:05 SC: This is certainly one of, in my opinion, one of those fun topics that we’re gonna be talking about here, the nature, the origin, the present status of hell, hell and damnation. What inspired you to write a book about this topic?

0:03:19 MV: Well, I’m fascinated by the association between people who are articulate and sensible, and the views that they nevertheless able to hold. My favorite example was, I didn’t write it… Put it in the book, was Galileo who has a reputation in our world anyway as being a scientist in rebellion against obscurity, obscurantism, and yet he spent quite a long while calculating how far beneath the surface hell would be, based on the notion of Dante’s, that at Satan’s naval is the actual center of the earth, and the presumed size of Satan. And he calculated that hell is therefore, the dome of hell is therefore 650 kilometers beneath the surface of the earth. And he announced these findings in great triumph to an audience of clerics.

0:04:21 SC: Wow.

0:04:22 MV: And there he is, an eminent scientist but nevertheless he happened to hold, he was able to hold these bizzare and contradictory beliefs in his head at the same time. So that’s what interested me most about it, I think at first.

0:04:41 SC: I didn’t know that about Galileo, I knew some of the things about Isaac Newton, he’d spent a lot of time on Biblical Exegesis later in life and so forth.

0:04:48 MV: Yeah, oh yes, Newton was another great scientist who had some completely lunatic ideas, but that’s not that uncommon.

[chuckle]

0:04:56 SC: It’s not that uncommon in fact, when you’re talking about Galileo, it reminds me, there’s probably plenty of work being done in modern science, which is of the form, “If you believe this thing, then let’s see the consequences of it.” But the thing that you’re believing will later be seen down in the future history to be completely silly.

0:05:15 MV: Yes, I think that’s definitely true. But then our now era, of course, people are just as credulous and just as conflicted as they were then. I mean, I read this morning that Joe Biden was now sacred jihadist who’s plotting to take over the government of the US.

0:05:36 SC: I didn’t know that, was that part of his new platform? [chuckle]

0:05:40 MV: It’s not part of this press release, but they are conspiratory theories, who can believe almost anything.

0:05:47 SC: Yeah, and it is a fascinating thing, that was why the very first episode of Mindscape that I did was with Carol Tavris, a social psychologist, and we talked about how people can justify their untrue beliefs.

0:06:00 MV: Well, yeah.

0:06:00 SC: But today, we’re talking about what some of the subjects of those beliefs are. So I do wanna get into the origin story of hell and so forth. But let’s just get our bearings with a quick survey of the present situation, how many people believe in hell? Is it universal among religions or there’s some exceptions?

0:06:17 MV: Well, almost all religions have a hell or many hells, and some of the Burmese hells for example, there are 40,040 hells in Burmese Buddhism, one for each sin.

0:06:32 SC: That’s a lot of sins.

0:06:32 MV: And obviously, some of those sins are going to be fairly trivial, because, for example, borrowing books and not giving them back pretending you’ve lost them, has it’s own hell.

0:06:45 SC: Uh-oh.

0:06:46 MV: Which I find actually sort of reasonable. And people who lie about their ages when they get married has its own hell, people who throw broken pottery on the fences has its own hell. And there seems in Chinese Buddhism, it seems a little unfair, but people with irregular teeth have their own hell too, which seems really unfair.

0:07:08 SC: That does seem unfair. Well, unless it’s their own fault, for bad dental hygiene.

0:07:12 MV: Yeah, well that’s true. It reminds me of the story from the New Testament, where Jesus kept casting out demons from people, and there were lot of demons in the New Testament, Jesus’s homeland seemed aptly thick on the ground with demons. And at least once as we know the gathering of swine he cast these demons in out into poor pigs, which seems, again, really unfair and would certainly get PETA on his case these days.

0:07:42 SC: What did the pigs ever do to you?

0:07:43 MV: Animal cruelty people.

0:07:44 SC: Yeah. [chuckle] So good, almost all religions have it, or the individual just today, again, to get our bearings, are most religious believers buying into this?

0:07:57 MV: In most recent gallop poll, people who believed in religion in the United States had actually increased in the last decade or so, from somewhere around 45% to somewhere around… Approaching 60%. More people curiously believed in hell than actually believe in heaven, which is seemed to me an indication of the peculiar nature of American politics. In Canada where I live, the belief in hell is less, about 30% to 35% believe in hell, where almost everybody believes in heaven. So we’re more optimistic.

0:08:34 SC: We’ll draw the conclusion, yeah that we can draw. Okay, so…

0:08:37 MV: But generally in Europe, also, more people believe in hell than believe in heaven, these days, which is I find interesting.

0:08:43 SC: Wow, so it’s both sort of universal between religions, and at least a healthy fraction of people in all the religions actually buy into it. So how… We’re chuckling here at this belief, but this is very, very widely held.

0:09:00 MV: Yes, it’s very widely held, and it’s interesting, and it’s across religion. Almost every religion with some exceptions, some interesting exceptions, believe in hell. And even those religions such as most variance in Buddhism, which don’t have a heaven, believe in hell and some of the Buddhist hells are grotesque in their litany of punishments. There are some people, for example, the Hebrews and the modern Jews, they’re not very good at hell. I mean Jews are good at many things, presumably, but they are not very good at hell. Jewish hell is a really boring thing. Everybody goes to Sheol, and everybody… Good or bad, evil or virtuous, they all go to the same place. And the Jewish faith is more interested in the here-and-now than in the after world, which I personally…

0:09:50 SC: That’s been my impression that they don’t have quite nearly the detailed picture of what comes after as Christians or Muslims do.

0:09:58 MV: No, because there’s no belief in the eternality of the soul, for one thing. So when you’re dead you’re dead. And so it’s better to concentrate on the here and now, than the way you might be after the candle is snuffed out.

0:10:17 SC: Yeah, so I really liked the part of your book where you talk about some of the origins of hell, and more generally in the afterlife, right? It sort of crept up on us in some way. There was, first, some belief in that there was some kind of afterlife, and then it could have kind of got elaborated on as time went by.

0:10:36 MV: I think, where it started probably was in the early animists days when people needed an explanation of why things didn’t work. Why a perfectly competent hunter fellow was killed by a perfectly normal and unaggressive animal. There had to be a reason for that. It doesn’t just happen. And therefore, demons came into the equation as an explanation for things going wrong. So I think the second thread of hell was, it seemed that life became… It seemed in urban… When civilization moved into the urban era, that life just seemed unfair, and it seemed that murderers and adulterers, and embezzlers who should be punished seemed to prosper much more than seemed decent. And so you had to find some way of finding out a way to punish them when they were dead. It had to be after they were dead, because it quite clearly nobody was punishing while they were here.

0:11:55 SC: Yeah.

0:11:56 MV: So that’s another way of inventing. That’s another reason for hell. I think the third thread of why people invented hell was as what former Episcopal Bishop Simone called a Soul control, which is basically a way of imposing discipline on the adherence to a religion, and threatening them with punishment when they didn’t follow the injunctions of the hierarchy. So I think those three things together, in a more modern version of hell, they are slightly contradictory, because if it’s a place of punishment, and therefore, Satan and the devil are agents of justice or it’s a way of… Ordinary citizens, sort of, getting their own back, which Satan is an agent of God in that sense.

0:12:54 SC: Yeah.

0:12:54 MV: But on the other hand, many of our religion, I think in Christianity portrays Satan as the willful and rebellious angle of God called Lucifer, who was punished and banished into the pit prepared for him. And so, you have this contradictory things where Satan is either a victim of his own hubris, as I put it in the book, and he seemed to be an ambitious lad, trying to take over the family business from dad who was the God, Or he was either that or he was an agent holding the evil doers to account. And the monotheisms have not really got this sorted out, the internal contradictions.

0:13:40 SC: Yeah, I mean, as part of the whole… We’ll get into this, I think. But there are… Once you have these supernatural beings with enormous power, and you try to use them as explanatory agents, there are sorts of contradictions that you run into, right? And the devil being both useful to the cosmic battle and also an agent of mischief is definitely one of those.

0:14:03 MV: Yeah. As expressed in many of the kind of establishment views of hell in Christianity, like Dante’s for example, most famous one where Satan is at the inner most pit of hell, imprisoned in ice and therefore eternity. And yet, somehow, he is able to roam the universe fomenting mischief and with malice of fore thought. So how these two things play out is, in most denominations elated really, because they don’t think about contradictions too much.

0:14:43 SC: But the idea of hell as a punishment, I got the impression from your book, that was a later addition to the idea that there was an afterlife, in Greek mythology, and so forth there was still an after life, but it was not punitive, in the same sense.

0:15:00 MV: That’s right, Well, it’s not… Even going very early into civilization, the ancient, ancient, ancient Egyptians believed in an afterlife, and you had to, as it’s predictable in Europe. In Egypt you had to get there by floating down a river and crossing through gates and so on. But those who failed to make the cut, and there was a being called the devourer of souls, who were standing by to grab hold of those people who failed to prove their virtuousness. But he just devour the soul, so if you failed that test, if you weren’t able to pass the gates, you simply disappear, there was no punishment, you were just dead, you were ended.

0:15:48 SC: And what was the nature of the test? Was it a moral virtue test or…

0:15:52 MV: Yes. Yes.

0:15:52 SC: Okay.

0:15:54 MV: There were judges who assessed how you had behaved during your lifetime.

0:16:00 SC: Got it.

0:16:01 MV: And there were people who were exempt from this tests, and those were the, no surprise here, the priests, and the Royal Family. They didn’t have to, they we automatically assumed to be virtuous.

0:16:14 SC: Very clever, yes.

0:16:15 MV: Very nice hedge.

[laughter]

0:16:17 SC: Well, that’s…

0:16:18 MV: And that same attitude was adopted by many of the later cultures in the early Mesopotamian cultures like the Ugaritic culture and the Canaanites pretty much had the same thing, when you were dead, you went to a place prepared for you, but there was no punishment there, you were just there. And in most cases, after a while you simply died. And the same thing was in all of the old African cultures, which I particularly am fond of. Where you became a… If you were good, you became a revered ancestor, and if you didn’t, to be forgotten by the living was hell enough, they were just… And they were so many dead then.

0:17:05 SC: It’s probably impossible to answer, but do people at least speculate about who is the first person to suggest that life continued after death, or where did that idea pop up on the scene?

0:17:18 MV: It’s very early, but I… We know it goes back to at least 3,000 BC, in the ancient Egyptian cultures. The occult of Osiris was one of the earliest and certainly that goes back… And there’s a lot of speculative evidence, speculative, I don’t wanna call it evidence, but speculations anyway, that the early Stone Age, cultures hundred gathering cultures also believed that there were… That you were able to survive death, if you succeeded in a series of assigned tasks, and those tasks were dictated by your family and also your tribe and your clan. And so I think the notion that there was a… That you didn’t die went back almost as early as the search for causality in the universe, as a search for the reason why things happened. It must have been a reason for something. It must been a reason for thunder, it must be the gods stumbling across the cloud. So it was a fairly short step from that to believing that there were supernatural beings to believing that, well, under the right circumstances we could join them.

0:18:37 SC: Yeah. And certainly what’s interesting there is that even before we officially had hell as distinct from heaven, we had this idea of judging, right? It’s very clear that the whole set up is very much in response to human beings desire to find reasons why things happen and justice and fairness in dealing with them somehow. If we can’t do it here on Earth, let’s say that the after life takes care of it.

0:19:00 MV: That’s right, exactly. And you have to rely on the judges to deeply know the inner lives of the souls who appeared before them, and they would know if you sinned during your life, and they would know how you sinned, and they would know whether you repented, and they would judge you accordingly. And in the Ancient Greek Hades, the mythology of Hades, there were three levels, it was a field of Asphodel, which were… Everybody rank while they waited for the judge. And then there was Elysium, which you went to if you where judged to be virtuous. And then there were Tartarus which was the inner most pit and flames of hell and hellfire, and that’s where the… It was from the… The Greeks would develop this notion that torture was very much a part of the after life. The Egyptians, they wouldn’t heed to that. Sometimes in later dynasties in Egypt, people were cut up and flayed and boiled and minced and skinned and everything. But it wasn’t… The point wasn’t the punishment, the point was just to get you dead. The Greeks developed this into a much more systematic thing and…

0:20:23 MV: But even the Greeks didn’t have eternity. You could probably… That was after the Christians and the monotheisms, too, introduced the notion that hell was an ending, that eternity was part of the formula.

0:20:38 SC: Well, that’s interesting. I guess it makes sense. I hadn’t realized that but, in this shift from polytheism to monotheism, a lot of things that were finite become infinite in some way. You had a bunch of flawed individuals being your gods in polytheism and then, everything is sort of perfect and everlasting up there in the sky or down below, once you become monotheistic.

0:21:04 MV: And in polytheism, they had these quarrelsome families of gods. And what happened to you could swerve and turn on its heel if a different God was prevailed on a different day. So, if a storm god was better than the god of agriculture, your crops fail. On the other hand, in some cases, the God of agriculture was able to put the storm God into a hole where he belonged, and your crops were wonderful. So, it was easy to explain why things went wrong because whatever happened, one God or either prevailed over another. And the quarrelsome families of gods were constantly at war with each other, and so, that made sense. When the ancient Hebrews invented monotheism, it no longer made sense that because God was infinitely able and infinitely everlasting… Was everlasting and he was, therefore impossible for him to be wrong and therefore, what happened, what had to happen is that we were wrong. We weren’t worshipping him or adhering to his ways in the proper fashion and therefore, he was right to punish us. But they were not the God’s fault anymore, it was our fault now.

0:22:28 SC: But never less, there is some universality in the idea. So, the Greeks came up with Tartarus, Tantalus, Tartarus?

0:22:38 MV: Tartarus.

0:22:39 SC: Tartarus was the place. Tantalus was a person, right?

0:22:42 MV: Yes, that’s right, yes.

0:22:43 SC: Okay. But still, the Hindus, the Buddhists, I think that Japanese folk religion and so forth, also came up with this idea that you would be treated badly afterward if you were bad while you’re alive.

0:22:56 MV: Yes. Well, both the Hindu and the Buddhist traditions, hell was not open-ended for obvious reason, because the reason you went there was not for punishment. The reason you were sent there was to work through the sins that you committed in life and once you had purged those from your system and the best way of purging them was to be tortured for a millennia. And that would certainly drive all thoughts of sin out of your mind, I would think, after a short while but you were then released on parole. You were let out to start your life again, and this could last for a very long time. In the Hindu traditions, the time you spent in hell varied from somewhere like 400,000 or 500,000 years to several million. It seemed like, it must have seemed like eternity to those people who were consigned there but it wasn’t forever.

0:23:58 SC: Right.

0:24:00 MV: And the same with the Buddhist traditions, there was an old tradition in Tibetan Buddhism, for example, where a mountain of sesame seeds, 100 miles on a side, a cube. And one small bird took one seed away every thousand years, and when that mountain had disappeared, then you are deemed to have purged your sins and you could be released.

0:24:32 SC: Well, okay, this brings up a question I’m definitely gonna ask. I’ll just get it out of the way right now. How do they come up with this specific idea? Someone had to invent that at some point, and do you think that they were, they knew they were just inventing it, or do they think that they were working it out, and did they think that there was a revelation?

0:24:53 MV: I think this remains a mystery because it’s at the same level of credulity that we still face with now and we face with the supernatural. Stories started and then, they became embellished and one monastery was competing with another, and one monk was telling tales that were more up-to-date and more modern and more lurid than the previous monk. And I think there was a competitiveness in what we would now call fake news, that they out did each other, but nobody knows who actually invented these. Buddha himself, somebody accepted him as real, and he had a long listing of the tortures, a rather enthusiastic listing of the tortures to which sinners would be subjected.

0:25:57 MV: But he also, like all of his followers, believed that in the end, karma would prevail and you would be able to work your way through your sins and purify yourself and then, you would be bathed in the River of Forgetfulness and you would start the whole process again. And that could… Where the endless numbers of millenia came from, I think there was a Japanese monk called Genshin, who had, as I suggested in the book, only a hazy idea of cosmological time who suggested that 10 trillion years might be about right for the average sinner to escape and nobody, as far I know has topped that.

[laughter]

0:26:47 SC: I’ll get some cosmologist on the scene, I think we can top that. But I also wonder whether the audience for these stories at the time, didn’t take them seriously… Like okay, sesame seeds, etcetera. Now we’re imagining that it was a doctrine hand-down from one high, but at the time it was just a fun story.

0:27:09 MV: I think that both of those aspects are correct. I think it was a story that they could be thrilled with. And also it was a way of inculcating in people who succeeded them, their children and their families, a way of threatening them with punishment if they didn’t shape up. So, I think both of those things happen in a way. I think almost certainly nobody thought towards themselves, “Oh my God, if I don’t behave now, I’m gonna be in there for two trillion years.” I don’t think anybody actually thought that, they just said, “Oh, it’s gonna be sore.”

[chuckle]

0:27:50 SC: Yeah, it’s gonna be bad.

0:27:51 MV: Yeah, it’s gonna be bad. “And then hellfire is gonna get me, and then knives are gonna get me and I’m gonna be immersed in noxious and obscene liquids, and… Yeah, it’s gonna be bad, but I’ll get out of it.” And I think they definetely believed that something was gonna happen, yeah. The natural…

0:28:08 SC: Okay. So, there are definitely stories being told. But there’s also… Some of those stories were stories about eye witness testimony, there’s a tradition of visiting hell. The ancient Greeks had Orpheus and so forth.

0:28:22 MV: That’s right.

0:28:22 SC: And the Christians have their own story.

0:28:24 MV: Aeneas was there. And if you look at the medieval period, which is where most of these… Most lured imaginings of hell came from in Christianity. It seemed at one point virtually every literate monk or nun had either visited hell, or had been vouchsafed hell in a vision, or talked to somebody who was there, and could vouch for the veracity of everything. And the stories were actually remarkably similar, I guess not surprisingly, because they fed off each other. But pits… Dark gloomy pits… Hellfire that gave off no light, fire that burned but didn’t destroy. Hellfire couldn’t destroy people, because it would be beside the point. It would be over too soon.

0:29:17 SC: Right.

0:29:17 MV: So it had to burn you, but you couldn’t die of it. And there was in some versions… Some of the visions, medieval visions of hell, there very sharp big crows, who were standing by to drag your entrails out through your anus. Well, they were lured versions, for sure. And you’d think, okay well after a while wouldn’t you sort of run out? But no…

[laughter]

0:29:45 SC: You can only have so many entrails.

0:29:48 MV: Apparently not. These sister were endlessly self renewing. And that’s part of the interesting and peculiar physics of the netherworld.

0:29:56 SC: And if you can go visit, like Aeneas and Orpheus… And Virgil maybe?

0:30:02 MV: Yeah, Virgil. Yes.

0:30:04 SC: It has to be located somewhere. I thought it was very funny in your book, you go through all the places where hell might be found. It wasn’t nearly as conceptual as you might think of it today. You might actually find the entrance if you looked hard enough?

0:30:17 MV: Oh yes, well the early Romans knew exactly where it was, it was just off Mount Etna. And there’s a grotto there which gives off what are called befitted gases, which are poisonous gases. And people had noticed that birds that flew past it, or that cows that wandered into it keeled over dead. And so that obviously was a place where… It was the anti-room to hell. And it was inhabited by one of the nastier Sibyls and the Gorgons. So, that was one, but there were many others. There was one in Vernon, there was one in Greece, there is also one in Turkmenistan. And as I said, a Johnny-Come-Lately hell was thought to be beneath Lough Derg, in Ireland.

0:31:12 MV: Because Saint Patrick found it there, and had reported that he had been given a tour, and there are many others. There’s one off the coast on the west side of the Gulf of Mexico, the Essex had an entrance to hell there. But a very popular one is in China, in the city of Fengdu, which was visited by numerous people. Governor Kwoh of one of the provinces was lowered into it on a rope. And he spend a nice time in hell, and was given a nice cup of tea while they explained the management of the system to him. And the city of Fengdu has been known actually for 1500 years, it’s been a repository of hellish law.

0:32:03 MV: The artisans of Fengdu are widely thought to be prosperous because they manufactured instruments of torture, which they then sold to the denizens of the underworld. And unfortunately Fengdu was drowned in the rising of the waters of the Three Gorges Dam, so that… But they still have a theme park there, which you can visit if you will.

[laughter]

0:32:29 SC: I suppose if hell is down there, why should we be surprised that there’s multiple entrances to it? It just makes things easy, little bit more efficient.

0:32:38 MV: And it’s almost over the gate. It’s a gated community, like heaven is generally. And you had to have Dante’s famous injunction., “Lose all hope, he who pass through here.” But almost all the… The ancient Egyptians had seven gates. The Zoroastrians had eight, I think, if I recall correctly. And pretty well everybody had at least one gate you had to pass through. The Legend of Ishtar descending into the underworld to visit her sister, she had to pass through eight gates. And losing an item of clothing in every one, she was forced to appear before her sister… Who was a thoroughly unpleasant goddess called Ereshkigal, who impaled Ishtar on a meat-hook, until the gods up above came and rescued her. So, there are always gates. And sometimes there are bridges you have to cross in order to get into hell.

0:33:38 SC: Are these gates keeping people out, or in?

0:33:41 MV: Always keeping people out, because [chuckle] when your time has come, you couldn’t go… You couldn’t enter hell until your time was ready., except Aeneas was able to go in, and of course Dante was able to use Virgil to get him in. So, there were passwords you could use, and people you could use that were able to get you in. But nobody ever tried to escape, because you couldn’t get out. That wasn’t part of the plan.

0:34:16 SC: It’s interesting, they would try to keep people out. I am very interested in how the specificity evolves. Obviously in someone like Dante it becomes huge. But as you mentioned in the book, if you read the Jewish Bible, the Old Testament, there’s almost no talk of hell, or Satan or anything like that. And there’s more of it in the New Testament, and even more in the Quran. So, people definitely became more interested in the details along the way.

0:34:42 MV: I think as hell in Christianity became more embedded in the system, the further away from Christ we got, the more grotesque the punishments of hell became. But it wasn’t really until the early medieval times, when the church was beginning to face competition from early free thinkers, and also later on of course, from Calvin and Luther. And they felt themselves to be under attack by people who were not as controllable as they should be. At that point hell became even more severe, and Satan turned from an agent of God and a guardian of the dead, into something evil and malevolent, who would grasp you if you didn’t behave.

0:35:41 MV: If you didn’t adhere to the tenets of the church, if you didn’t listen to your Bishop, if you didn’t follow the threads that they told you to. And if you were a protester, or Protestant as it became later, then hellfire would get you for sure. It’s the same syndrome as the witch trials of Europe in the 17th and 18th century became more and more aggressive, the more that the church felt itself under attack from dissenters. And so it’s no wonder, for example, that Germany where many of the early dissenters began, there were more witches that burned and hanged in Germany than in any other place. So, it’s predictable that the hierarchy of the church exaggerated, and made more appalling the punishments that awaited you if you didn’t adhere to the proper way of doing things.

0:36:48 SC: If we just stuck to the New Testament, or even just to the gospels, can we say anything about what the early church, or what Jesus would have thought about hell? I think there’s some debate on whether Jesus was clear that you must go to hell.

0:36:58 MV: Jesus, in the Gospel, had very little to say about hell. There were a couple of things when Matthew quoted him as saying, that certain people would be consigned into the eternal flames. And Jesus was big on the kind of wailings and gnashings of teeth that went on down in hell.

[chuckle]

0:37:20 MV: But he never said where it was, and he never said much about who went there, and who didn’t. Hell at that point was really, according to those stories, was really an imprisoning place for the opponents of God, and it was mostly Satan, not so much humans. It was really only as the church grew in its stature, and got further away from the writers of the gospel and the supposed sayings of Jesus himself, that they started to invent the more aggressive punishment that sinners would face if they didn’t follow the Holy Church.

0:37:58 SC: Jesus did talk about heaven quite a bit, and how you needed to go through him to get through to heaven. And maybe it was just assumed that not getting into heaven meant you went to hell?

0:38:08 MV: I think that was the assumption. And certainly, the early church believed that anyone who didn’t follow Jesus, or was born before Jesus existed, would automatically be consigned to hell. And in fact, one of the stories has Jesus doing his harrowing of hell, that is visiting hell after he was crucified… Or in some versions, while he was still on the cross, going down to rescue people, like Adam, and the first people who were in hell because they came before him. But he got them out, and he was able to get them out. So yeah, everybody who wasn’t saved by Jesus, would be automatically consigned to hell.

0:38:47 SC: Yeah, this is a fascinating story to me. It comes into one of the sets of contradictions. Somehow in the history of religion there are certain things you want to be true, and it might be difficult to make everything compatible with everything else. So, the harrowing of hell story is right there in the gospel, or at least in one of… I forget which book it is.

0:39:06 MV: Yeah. Although there’s no real detail. Most of the real stories about the harrowing of hell were from the apocryphal gospels, or some of the Gnostic Gospels… For example, The Gospel of Nicodemus, The Gospel of Bartholomew, which were rejected by the early church fathers, and not incorporated into the canon. That’s where most of the stories of the harrowing of hell came from. And there were also some earlier versions of the stories, which were in fact pre-hell, I think called “The Testimony of Truth,” which is one of the Gnostic Gospels, had stood its whole tale of Adam and Eve and original sin on its head and in that sense, the gospel was very critical of God for grudging Adam and Eve the knowledge. Why would he do that? What a malicious grudger he was, as the gospel put it. And in that case, the serpent, who was Satan, was portrayed as the sensible worldly person, and God was a kind of a peevish person, simply punishing people who didn’t listen to him properly. So, there was a lot of variance on that. But in the actual gospels that are in the New Testament, there’s actually very little about hell.

0:40:30 SC: Maybe it’s worth, for those who don’t know about this whole story… Maybe it’s worth just talking a little bit about how what we now consider to be the scriptures came together. It wasn’t like there was one very clean process, by which either the Hebrew Bible or the New Testament were just written down. There were a whole bunch of documents floating around and some councils had to decide what was in and what was out. But the people at the time had might have read all of these stories whether or not they were in or out.

0:40:58 MV: Well, they did… I think they probably did read many of them, and also the ancient prophet… Hebrew Prophets were much more into apocalyptic visions than the Sanhedrin or the Hebrew authorities were. And a lot of those survived and were transmitted into stories that were picked up by the Christians, and also Christianity adopted freely from Zoroastrianism, which was… Which had a very well-developed dualistic theory of a universe. It was in contention between the forces of virtue and the forces of evil.

0:41:42 SC: And that was one of the first monotheistic religions that really caught on?

0:41:44 MV: Yes, it was the first multi-national monotheistic religion, I think. And Christianity picked up a lot of its thoughts about hell from Zoroastrianism, from the Greek mythologies of Hades, from their stories of the torches of Prometheus, and having his liver pecked out for eternity by a vulture. And so… And these stories accreted as they went along, and then as the early few centuries of Christianity proceeded, they tended to agglomerate some of the early stories and accumulate them, and embellish them. And by the time you got to the seventh and eighth century, the time of Charlemagne for example, the visions of hell had become reasonably predictable that there was a… It was beneath the earth, it was… There were cauldrons of boiling oil, there was hell fire, there were demons with the pitch folks, and those were worked into almost all of the visions that followed in the next few centuries, except Satan, who became more… Less and less a servant of God and more and more a creature of evil as we proceeded through the centuries.

0:43:12 SC: Well, Satan’s story is more complex, I think, than most people think. Certainly, it’s more complex than I knew, until I read your book. There is… For one thing, there’s the idea of Hades, which was originally the person, and then it became a place maybe with a person, and then there’s co-bosses at different times, and Lucifer versus Satan and all that.

0:43:34 MV: Yeah. Where, it did get very confusing because chronology is not simple.

0:43:37 SC: Yeah.

0:43:37 MV: Hades was, first of all, a place. And then, yes, Hades also became the god of the underworld. His brothers were Zeus and Poseidon, and he drew the short straw, and drew the underworld. And was always regarded as as horrendous to look at, and pitiless and monstrous and, which I argue in the book was a bit of a bum rap because his brothers were just as bad. His family was not an exemplary family. His father was one of the titans, Cronus, swallowed Hades and some of his siblings when they were infants. And Zeus, showing some of the leadership skills that made him a chief God later on, forced his father to vomit up the children and rescued them. And then the children banded together and prepared a pit for the Titans, and banished their father into this pit. And that was the earliest version of the underground place to store the bad guys.

0:44:43 SC: Right. Family is always hard. [laughter]

0:44:45 MV: Family is always hard, yeah. And so, the early Christian hell… Early versions of Christian hell started more in the same way, as a revolt against God. Lucifer and his cohorts were rebellious, were not taking orders. And God, in a fit of anger, again, sent the Angel Gabriel to prepare a pit for Lucifer, which was basically borrowed holus bolus from the Greeks. There was the same story, just updated with new names. And that’s where Satan came from, and he was abolished. If you listen to Milton and people… From the Egyptians he borrowed, not only was Lucifer abolished but about half the heavenly host went with him. So, as I said in the book, it doesn’t show much for God’s management skills if half of his crowd was revolting against him. But anyway, so both the ancient Greek hell and modern hell started with a revolt in heaven.

0:45:51 MV: But Hades and Satan were often in many early Christian writings cohabiting or co-existing in hell. Hades was the ruler of hell, and Satan was the prince of death. And sometimes, they worked together, and sometimes they didn’t. And there was a fair amount of quarrels, quarreling going on and there was some, I mean there was one gospel of Bartholomew, it was wonderful in depicting the panic and the ineffectualness of both Satan and Hades when Jesus came down to rescue Adam. And they kept blaming each other for inviting him down there in the first place.

[chuckle]

0:46:41 MV: Again, it seemed more ineffectual old fractures and they drew skillful evil managers of the dead.

0:46:48 SC: Yeah. But the early Christians thought, like you said, both Satan and Hades were powerful figures in hell. As far as I can tell, Hades has disappeared from the official doctrine.

0:47:00 MV: Yes, Hades disappeared, sometimes he crops up as a name Beelzebub.

0:47:05 SC: Okay.

0:47:06 MV: But that is… Beelzebub is derived from the Mesopotamian God Ba’al, who has also visited the hell to wrestle with death at some point. But it’s very confusing, because there’s no consistency. Beelzebub, sometimes Hades, sometimes it’s Lucifer himself. Hades was originally the master of hell and later on was consigned to a lesser role, as a kind of, in-keeper and chief. And after a while he just vanished from the… As the Roman religion was supplanted by Christianity, Hades and the other pantheon of the Greek gods disappeared. And became, faded into the background.

0:47:47 SC: It’s not even clear the relationship between Lucifer and Satan, is that right?

0:47:52 MV: Well, no, I think it’s pretty clear that Lucifer is Satan. Again, there are contradictions in the stories. And then the other version of Satan is… Satan is, as you probably know already, in Hebrew simply means adversary. It’s the word for adversary. And he was a… He was originally, one of the servants of God and he was the one who goaded God into, for example, testing Lot with the boils that he would then try putting him through the trials of his faith. It was Satan and God who cooked up this little scheme together. He was…

0:48:30 SC: Sorry was it Lot or Job we’re talking about?

0:48:32 MV: Oh Job. I’m sorry, Job, yeah Job. And Satan was really on the… In the Royal Court. He was one of the children of God, so yes, he was also Lucifer and he was Satan at the same time, and it was… There were two quite separate views of how that developed. The Christians turned him into Satan and lost Lucifer, and some of the early Christians thought, well, Lucifer could easily be redeemed. He wasn’t so bad, he had a bad press. He could be saved. And this was a minority view that was punished by exile, and casting anathema on people like Origen for example who was an early Christian gadfly.

0:49:31 SC: And one of these contradictions that you mentioned is the idea that in most of the stories, at least as they developed in the Christian telling, hell pre-dates human kind, is that right? The fall of Lucifer and so forth, happened first, and it was…

0:49:48 MV: Yes that’s right.

0:49:49 SC: Like you said, used as a prison for the bad angels. And then re-purposed I guess, as a place to keep the bad people.

0:49:56 MV: That’s what… It’s essentially what it was and there was… It was basically what they called the innermost pit, which is where Satan and Lucifer, or Satan aka Lucifer and his cohort were imprisoned, and originally it was just a hole in the relish and God instructed Gabriel to heap sharp rocks on their head and keep them in down in there. So it was a pretty primitive arrangement, it was just a pit with rocks. And that became much more embellished as time went on, and it didn’t seem sufficient that there would be a… That Satan was just imprisoned in there with nothing much to do and you needed somehow to deal with sinners. You needed some way to control their actions. You didn’t want to let them enter into any more heresies than you could hear of. And so yes, it became, in your word, re-purposed into a prison for malefactors and not just a prison for the chief, the devil in chief.

0:51:05 SC: And the Christians certainly had a good time embellishing and complicating the notion of hell. Did Judaism not do that? It was not a big deal certainly in the Old Testament times, but…

0:51:18 MV: No.

0:51:18 SC: Is there some tradition in Judaism also coming up with some stories about the afterlife?

0:51:23 MV: As… After the Babylonian captivity, as people returned to Israel, they were developments in this universal notion of Judaism that everybody just went to Sheol and it was a place where there was no activity, there was nothing to eat, and nothing to do it was just dark and gloomy. And after a while, the same impulses came into the Judaic thought that somehow, evil-doers would be… Prospering more than they should and so, Sheol became divided into two, a place for the sinners and a place for the virtuous. And it was a fairly short… Would be a fairly short step from there for the evil-doers to be punished and the virtuous to be rewarded. And, indeed there were some streams in Judaism that believed, to some degree, in some sectors, still believe that there would be a… That when the Messiah comes, and Abraham is resurrected, that those virtuous would be accepted into a world which is more bucolic and more paradisaic and the sinners would therefore just be forgotten and not killed and not tortured but just forgotten.

0:52:48 SC: Forgotten. Whereas, on the other side of things, Islam comes along at a time when the idea of hell is already pretty fully developed and, as far as I can tell, they… They took to it enthusiastically.

0:53:00 MV: Enthusiastically, and they have a number of rather inventive embellishments. The diet of hell is… There’s a particular root, which if you pour it from the sap, if you pour a drop of the sap on the earth, it would poison all life on earth. Well, the sinners are forced to drink that. And of course, they destroyed it and then they would resurrect it immediately afterwards. Also, they were very good on… Muhammad himself was very good on the ways that you could, in fact, torture people without them dying, pouring incredibly hot boiling liquid on top of their heads and then it would run through the body and pool out at their feet. That was one of his favorites. And then of course, once it was out you would be resurrected and the whole process would start all over again. But diet was much more an interesting facet of Islamic hell than… I didn’t see anything and anybody, Dante or anybody, who suggested what you might actually eat.

0:54:10 SC: Eating… Yeah.

0:54:11 MV: Nobody got that far, but Islam was big… Was good on that. So…

0:54:14 SC: And how much… Go ahead.

0:54:15 MV: No… And when… And in hell fire. The Christian fire still remain the hottest furnaces of all. In Islam, you use fire consistently and mostly, to burn off the skin. That was what they were interested in more. They weren’t interested that much into mincing and cutting. And then that was left with the Buddhists to get into that sort of thing. The Christians would get into boiling in oil. But they were… Like flaying was part of what Islamic thought would be appropriate punishment in hell.

0:54:49 SC: And I would imagine that in any of these mature religions, there’s both a set of stories and things that people tell each other. And then there’s sort of the official doctrine. How much of the specific story of hell and who is the boss in it and who lives there, and what happens to you there, is embedded in… The Catholics are probably the best at writing things down, right? But in, in any of these religions.

0:55:12 MV: Yeah, but even so, there’s very little. It’s not in the catechism, and it’s not in the official doctrines of the Catholic Church. But in the writings of the Jesuits, of the writings of early bishops, Adamnan, for example, who was a famous Irish Bishop of the… I think the 7th century. The embellishments came outside the canon, generally, and so they adopted from each other, they adapted from each other, and they embellished on each other and others’ work and it’s… But very little was in the… The catechism of the Catholic Church itself does say that hell is an actual place, where actual sinners are going to be actually tortured. But they don’t get into the specifics on that, that’s left for the commentary, the commentariat.

0:56:09 SC: And wasn’t there a rumor going around that Pope Francis had mentioned to an interviewer that maybe hell wasn’t, in fact, literal that way?

0:56:16 MV: Yeah, I think the Catholic Church has backed away from this. It’s still in the catechism, but Francis, for example, said that hell is simply a radical separation from God, which is a much more intellectual and not physical version of catechism.

0:56:36 SC: Not so much burning there.

0:56:37 MV: Not so much burning there I know, it was self-torture in a sense. And he… The Vatican rapidly backpedaled when he was quoted as saying this with a Italian journalist. But it wouldn’t have surprised anybody if he had said it. The hierarchy is skeptical of the literal interpretations of gospel these days and that should be their view, it should be interpreted to some degree as metaphor, and to some degree as an explanation, but not to be taken as literally as it used to be taken. I think that’s quite common in the Catholic Church even now.

0:57:19 SC: Yeah, so I did… I actually did research for this podcast interview. That is to say I went on to Google and I asked what the current beliefs were. It’s easy to find opinion polls, at least in the US, worldwide it’s probably a different story but… So what I found was that right now 72% of Americans believe in heaven, it’s maybe falling very, very slowly, but it’s not significant; 58% are believing in hell and that’s been consistent for at least 10 years, but I think it is higher than it used to be. And interestingly, so 58% of Americans believe in hell, but among American Buddhists it’s 32%, among American Hindus it’s 28% and among Americans who don’t have a religious affiliation is 27%. So the…

0:58:07 MV: So that’s the astonishing thing. You could believe in hell, if you’re not religious.

0:58:11 SC: Yeah, it certainly serves some purpose there.

0:58:13 MV: Because it’s very convenient. It’s a convenient concept to have a hell, because it explains so much.

0:58:21 SC: Well, and 70% of Americans believe in Satan. And that is apparently up from only 55% a couple of decades ago. For whatever reason, belief in Satan is skyrocketing in the United States.

0:58:37 MV: Well, their… If people who look around and see what’s going on in the country believe that some malevolent force must have a hand in it somehow, otherwise why would it be… Everything be so crazy? It’s got to be some explanation, some reason for it.

[chuckle]

0:58:57 MV: And Satan, even if you don’t believe in hell, Satan is a malevolent force patrolling the universe. He doesn’t necessarily have to have a home, but he is a force that’s a controverting force to the positive force of what you… What if you call it God, Jesus, Spiritualism, Buddha, Yama, whatever your particular religion give you charge.

0:59:24 SC: I was trying to figure out whether I should be surprised, whether it’s easier to believe in hell without Satan or to believe in Satan without hell. Probably is easier to believe in Satan without hell.

0:59:34 MV: I would think so, because hell is such… There’s so much specific detail about what it is, what it looked like, what the meteorology is like, and what the topography is like, and the imps and demons that run it have to have a hierarchy. It’s a very complicated thing, where Satan just is a malicious spirit who could be manifest anywhere and at any time in any person. So yeah, I think it’s much easier to believe in the devil than it is to believe in his abode.

1:00:07 SC: And believing in Satan certainly does help make monotheism a little bit more consistent with our experience of the world, right? If there were just a single omnipotent, benevolent God and no other powerful supernatural creatures, he has a lot of explaining to do.

1:00:24 MV: Well, it’s one of the difficulties of monotheisms and difficulties of believing in a universal loving and just God is the explanation for evil, and therefore, Satan is a very convenient explanation for that. It’s never quite worked out why an all-powerful, all-seeing and all-omnipotent God has allowed the force of evil and the force of evil to appear and to compete with him. The theory is that, in a sense, Satan is God’s creation, because it helps to impose discipline and explain things that God himself is unable to do, and so he’s acting as God’s agent in that sense.

1:01:14 SC: Yeah, so just letting some of my personal opinions leak in here, I’m sure I’ve been doing it the whole hour but I’ll do it even more explicitly here. Yes, there’s the problem of evil, in religion, if God is good and omnipotent, why is there evil in the world? And like so many other attempts to answer these conundrums in the context of religious belief, the idea that, well, there’s also Satan and that helps explain the existence of evil, seems more like a deferral than a solution, right? Well, sort of why is there Satan?

[chuckle]

1:01:46 MV: Because… Yeah, because it doesn’t explain anything. The explanation is just at one step removed. That the why… Satan causes it but what caused Satan? It’s the same argument when people are arguing for the existence of God, there has to be a God because who caused the universe? Well then, you argue who caused God.

1:02:06 SC: Exactly… Yeah.

1:02:07 MV: If evil exists, what caused evil? If Satan caused evil, why does Satan exist because God caused Satan?

1:02:15 SC: Yeah.

1:02:15 MV: And there must be a reason why God did that. And the reason is, evil happens anyway, and it seems that God is not as omnipotent and all-powerful as the doctrine would suggest.

1:02:33 SC: I think one of the reasons why we came in contact is because you wrote this book and I provided a blurb for it and that’s because I was quoted in it and the reason why I was quoted in it is because there was this discussion started by a New York Times column by Ross Douthat.

1:02:50 MV: Yeah.

1:02:51 SC: Where he is making the argument, which he’s not the first to make, that without the notion of hell, there’s no reason to be a good person. Without the concept of punishment afterward, anything goes, and that’s bad.

1:03:03 MV: Yes, I think and it’s quite common. And that’s a very… It’s a very condescending view of human life, it seems to me, because if you’re automatically going to be evil, unless there’s a controlling force that forces you to be good, it doesn’t say much for your spiritual development, it doesn’t say much for your personality, it doesn’t say much for your society in which you’re embedded, and it seems that why should we have… Why should people automatically choose to do bad things, if there’s not a control over their activities? It seems that… Why does… Why does Ross Douthat… Why do people like Ross Douthat think that you’re gonna automatically be evil if you’re not forced to be good? If you’re a good Christian, and in your religion, you believe in a God, why couldn’t reverse be true? Why couldn’t you be good unless you’re being forced to be evil? But they don’t seem to confront that. They seem to doubt… You need the punishments of hell in order to be bullied into line in order to do the right thing and that seems to be a very condescending view of humanity.

1:04:24 SC: Yeah, I worry that I’m being ungenerous here because I’m commenting on people who I disagree with, but it seems worse than ungenerous to me. It seems horrifying, the idea that without this eternal damnation, in this particular case, there’s no reason to be a good person and that makes me think like, “Really? You don’t… You can’t think of any other reasons to be a good person other than that?”

1:04:48 MV: Because if you confess to be an atheist, and if you are in impolite or even polite company, people will say, well, how… Why are doing good then why don’t… Why don’t you just go to and murder somebody because there’s no… You don’t have to worry about any punishment in the afterlife? Well, most people don’t want to murder people, they just…

1:05:11 SC: I’d like to think that, yeah.

[chuckle]

1:05:12 MV: Right. No, I think it. But your… The thing that I liked about your quoting in your essay against Douthat was, why is there no concept of parole? Why is it… Your life is only 80 years, but your punishment is eternal? That just seem disproportionate.

[chuckle]

1:05:32 SC: Well, it does. And I think that even more… Even for heaven that the same argument goes. I think that the people who come up with these ideas, their imaginations, we’re all finite human beings. It’s just very hard to stretch our imaginations to truly embrace infinity or eternity in that way. How can you even be happy and content in heaven for infinity years, is something I don’t quite understand.

1:05:56 MV: Well, I know it’s… I did a very brief chapter as a detour to heaven but there’s… The writings… The historical writings on hell are much more interesting and comprehensive than the writings on heaven, which have a few and banal and it’s at its best and the… I kept coming across this description of heaven as the throne of God surrounded by holy angels singing “Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord our God” day and night, for ever. To me… They used to say The Devil has the best music but he also has a much better story to tell than that.

[chuckle]

1:06:34 SC: Everyone agrees that the Inferno is much more interesting to read than the Paradiso, right, when it comes to Dante. It is… And I think there’s a… It’s a broader thing going on, which is that, human beings tend to under-rate the extent to which life is about change and process. They think there’s something perfectible about life, whether you’re Buddhist, or a Catholic or whatever, and the idea is to reach that perfect state and stay there. And I think that as a naturalist myself, accepting that life is about flux and change and impermanence, is a much more grounded realistic way to go.

1:07:11 MV: And yeah, most religions are believers in perfectibility, even there was those who are… Who do not have an eternal punishment and don’t have a heaven. The idea is to work your way through various incarnations until you have completely purged yourself of bad doing. And then you have become one with the universe and you have become perfectible, and there’s nowhere else to go. The religions don’t really get into what happens then, because there is really no then, then. There’s nowhere to go. Once you’re perfectible, then what?

1:07:48 SC: Yeah, and so I guess as one final thought from my side, it’s interesting you say, “Talking about being an atheist in polite company,” because there is such a thing… There is an idea of what polite company is. We get it on TV and in the media, and there’s certain ideas that are taken for granted, and both sides of any one debate complain that their extremist view is not represented in polite company. I do think that the sort of media-approved version of what is polite and okay, says that being atheist is worse than being religious, but it also says you shouldn’t be really religious, right? I mean, it would mock you if you believed too directly in Satan, hell, and demonic possession, even though most people do believe that.

1:08:36 MV: I think fundamentalism, in that sense, is not polite company itself, yes. I think people do not like extreme positions. I think social compromises are necessary, but I still think it’s more acceptable to be slightly religious than it is to be slightly unreligious.

1:08:55 SC: Yeah, I think that’s a valid point.

1:08:56 MV: Although, I think that’s changing pretty quickly. I don’t know. The newer generations seem to be retreating fairly rapidly from the… At least from the organized church, if not from spirituality, itself.

1:09:08 SC: Well, the great thing about polite company is that it reverses itself all the time, and pretends it never has, right? [laughter]

1:09:13 MV: Oh, yeah, and it does. That’s a universal change. You’re right, it does. So yeah, and that’s a universal change. You’re right.

1:09:17 SC: That’s right.

1:09:17 MV: That’s where we are.

1:09:18 SC: So, I do. I’m pretty optimistic. I’m a pretty… I don’t know. Maybe optimistic is a sense of prediction, but I’m interested in the fact that people who don’t have any religious affiliation are growing as a set of people, but I’ve learned now, from looking at things from your book, that the set of people who believe in Satan is also increasing dramatically. So I’m going to have to try to understand that better. That’s a little concerning to me.

[chuckle]

1:09:41 MV: Yeah, and the notion that exorcisms have been returning to popular culture is an interesting thing to me, because demonic possession is not necessarily Satan, but it’s… There are people who certainly believe in that. And I was fascinated to learn that you could actually now book an exorcist online. There are a number of them available for freelance exorcisms, and their business seems to be flourishing.

1:10:10 SC: Part of me has respect for that. If you believe in Satan and devils and demons, and then why not believe that they possess people and you should get them exorcised? It’s almost worse to me if you sort of profess belief in that, but not really, right? I like consistency in my anthologies.

1:10:26 MV: If you profess belief and then believe that it’s impossible to change and get rid of them, that would be an even more depressing outcome.

1:10:32 SC: That would be depressing, yeah. Alright, but… [chuckle] So it’s a mixed message here, but Marq De Villiers, thanks so much for being on the podcast.

[laughter]

1:10:39 MV: Thank you very much, Sean.

[music]

[/accordion-item][/accordion]

The Sumerians had a rather extensive Hell-underworld for the dead but it was one ruled, in part, by Ereshkigal,

a goddess who passed judgement on the dead. Seems females were edged out of management thereafter in most religions or myths..

Sean, in Judaism there is NO concept of hell as a place of eternal torment. It’s completely foreign to Jews.

The Harrowing of Hell is an excellent rescue ops story, too oft forgotten.

The scholar Jeffrey Burton Russell did a multi-book investigation of concepts of the devil in ancient cultures and the West that I would recommend for those interested in that kind of thing.

The Christian story of Lucifer may also draw inspiration from Ezekiel 28:11 “Lamentation over the King of Tyre”. This mentions an exalted one in the company of guardian angels who is cast down into the Pit. Arthur C Clarke drew inspiration from this for his short story “Guardian Angel” which was then incorporated into “Childhood’s End”.

Tema interessante, e, bem desenvolvido.

Julgo que a origem do termo inferno, é latina-“infernum” que significa “as profundezas”, “mundo inferior”.

Atualmente, correntes de pensamentos atuais, opinião s/inferno, não um lugar físico, mas, um estado de espírito. Não é consenso entre os Cristãos!

No inferno, estamos todos nós, muitas momentos ao longo do nosso “dia a dia”!! 😊

O medo do desconhecido, “algo” que sustente a nossa eternidade, origem de todas estas “histórias”!

Obrigada, Sean Carroll, e, Marq de Villiers

India have more examples of hell and heaven.

Book 1: Untouchables of India (cast baised division of people and unequal laws for people).

Book 2: Hinduism is nothing but brahmanism.

Summary is people of India are divided on past basis they are confused what to do in present.

Dividing factors are mainly Hindu, Muslim, Brahman (dominating people in India), RSS (organization).

Also 50% seats in govt. Jobs are reserved for socially Backward of cast.

Recently 10% reservation given to poor people irrespective of cast.

All this is the base for dirty politics all the time I want to escape from.

Pingback: Episode 48: Marq de Villiers on Hell and Damnation – Science Fiction

With respect to the Ross Douthat’s belief that humans would go on a rampage of evil if there was no threat of punishment, there is a fantastic couplet on the subject by Ghalib (1797-1869), considered the greatest poet of the Urdu language. It is impossible to translate but there is an excellent commentary available from Professor Frances Pritchett from Columbia University. In essence, Ghalib suggests that Heaven should be consigned to Hell to test Douthat’s proposition. http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00ghalib/118/118_02.html