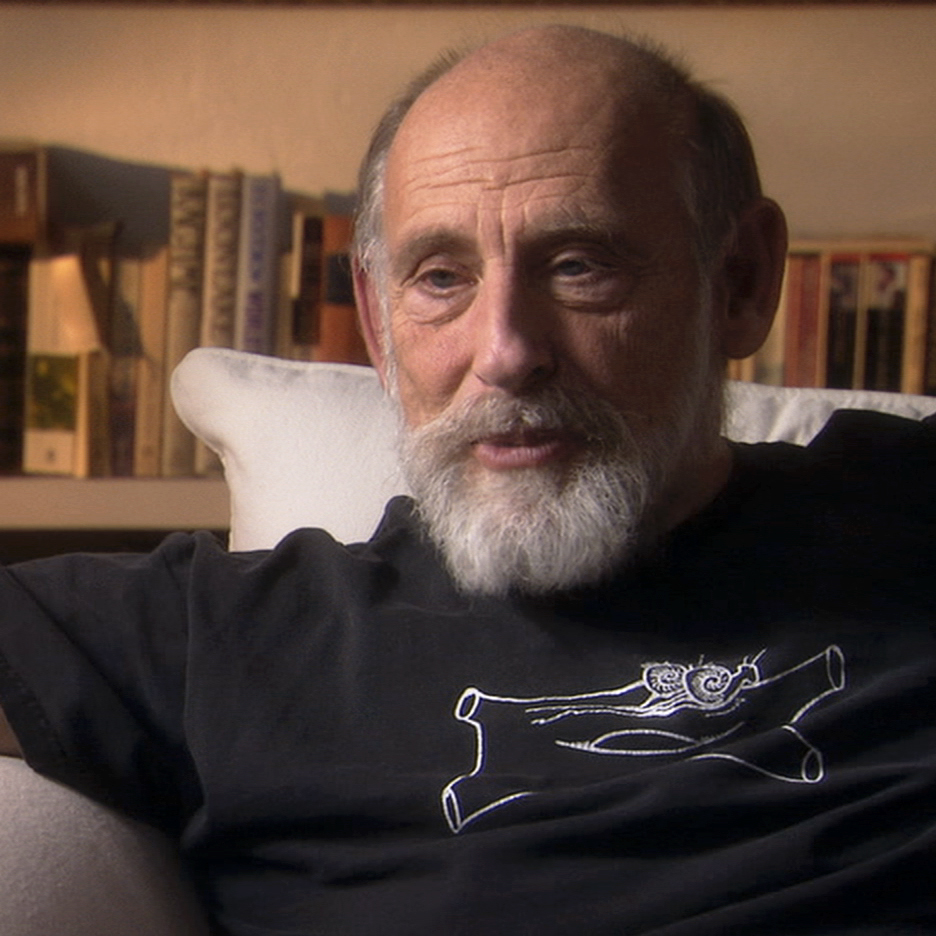

For decades now physicists have been struggling to reconcile two great ideas from a century ago: general relativity and quantum mechanics. We don't yet know the final answer, but the journey has taken us to some amazing places. A leader in this quest has been Leonard Susskind, who has helped illuminate some of the most mind-blowing ideas in quantum gravity: the holographic principle, the string theory landscape, black-hole complementarity, and others. He has also become celebrated as a writer, speaker, and expositor of mind-blowing ideas. We talk about black holes, quantum mechanics, and the most exciting new directions in quantum gravity.

Support Mindscape on Patreon or Paypal.

Leonard Susskind received his Ph.D. in physics from Cornell University. He is currently the Felix Bloch Professor of Physics at Stanford University. He has made important contributions to numerous ideas in theoretical physics, including string theory, lattice gauge theory, dynamical symmetry breaking, the holographic principle, black hole complementarity, matrix theory, the cosmological multiverse, and quantum information. He is the author of several books, including a series of pedagogical physics texts called The Theoretical Minimum. Among his numerous awards are the J.J. Sakurai Prize and the Oskar Klein Medal.

0:00:00 Sean Carroll: Hello everyone, and welcome to the Mindscape podcast. I'm your host, Sean Carroll, and today's episode, I think it's safe to say is one that has been anticipated for quite a while by a lot of people out there in Mindscape land. Now, usually I'm an ornery guy, and if a bunch of people demand that I do this or that, I sort of resist doing this or that for exactly that reason. But in this case the wisdom of the crowd was absolutely on the right track.

0:00:24 SC: So we're very happy to have Lenny Susskind on the podcast. To those of you who are physics fans, Lenny is very well known for his technical work, for his popular work, for his semi-technical books, The Theoretical Minimum. And within the physics community extremely well known as a storyteller, a mentor and a guiding visionary of the field. For those of you who don't know him, you're in for a treat, both the personality that comes through very clearly and also the subjects that we're gonna talk about. Lenny was one of the founding fathers of string theory. He has done an enormous amount of work in quantum field theory in the standard model, but today at the age of 78 he is leading the charge to understand the black hole information laws paradox.

0:01:10 SC: This is the thing that Steven Hawking bequeathed to us in the 1970s when he realized that black holes give off radiation, and if you throw information into a black hole, how does that information come back out in the radiation? Or even, does it come out? So Lenny, like I said, is one of the leaders in tackling this problem, which is probably the single biggest clue that we have to ultimately constructing a theory of quantum gravity. So this has led people into things like the AdS/CFT correspondence, IT from Qubit, a whole bunch of very mind-stretchy ideas.

0:01:44 SC: So we're gonna do our best in this podcast to bring those mind stretching ideas down to earth, to make them understandable, and to convey some of the excitement that physicists like Lenny and I, because we work in very, very similar fields, really feel these days about the progress that's being made and the prospects for what's going to come very, very soon. So buckle up. This is gonna be quite a ride and I think you're going to like it. Let's go.

[music]

0:02:14 SC: Lenny Susskind, welcome to the Mindscape Podcast.

0:02:28 Leonard Susskind: Hi, how are you?

0:02:29 SC: So, one question I'd like to ask of people who are identified as string theorists is, are you a string theorist? Do you call yourself that?

0:02:37 LS: I really don't, I really don't. I had a lot to do with it in the beginning, and then more recently, but I like to just think of myself as a theoretical physicist.

0:02:47 SC: I think that's smarter, 'cause then you can do whatever you want, right? [chuckle]

0:02:50 LS: Yeah. You do what you're curious about. And one time I was curious about that, the other times I was curious about other things, and I tend to follow where my nose leads.

0:03:01 SC: Right. Just so we can get it on the record, do you have a feeling for the present state and possible future of string theory as a field?

0:03:09 LS: Yeah, I think I do. I can't tell, and I don't know if it's gonna be the, let's call it the theory of everything. I hate that term but I'll use it anyway.

0:03:19 SC: Yeah, people get it.

0:03:21 LS: Whether it's going to describe, in any of its given forms, whether it's going to describe nature as we know it. But I can tell you what it has done. It's provided some very, very concrete, very, very precise, let me call them examples, of theories, models, however you want to call them, that contain gravity, that contain electro-dynamics, that contain particles, that contain fermions and bosons, the various kinds of particles that we have in nature, and looks a lot like what we think nature looks like. At least when we look in the laboratory, we see particles, we see gravity, we see all these things, and they're there.

0:04:05 LS: And so, what this provides us with is a highly precise mathematical situation where we can try out ideas. And one of the ideas that was most important in all of this was the consistency of having quantum mechanics and gravity in the same mathematical theory. And I think by virtue of string theory, and its spin-offs, I think we know with certainty now that mathematically quantum mechanics and gravity can fit together sensibly and consistently. That is no small thing.

0:04:40 SC: And it might not be our world that we live in, but it's possible in that space.

0:04:42 LS: It might not be, that's right, it might not be, but we now know the two can fit together, that this idea that there was some breakdown where quantum mechanics and gravity simply could not fit together, I think we're quite sure that that was wrong.

0:04:57 SC: And one of the great guide stars we have in this game is the entropy and evaporation of black holes, and you wrote a wonderful book that I'll plug, The Black Hole War. You've written many wonderful books, but that was a great one.

0:05:10 LS: No, not many.

0:05:10 SC: Well okay, maybe a couple.

[chuckle]

0:05:13 LS: A few.

0:05:13 SC: I've blurbed a couple, so I have to say they're wonderful.

0:05:15 LS: No, I wasn't arguing whether they're wonderful, I was arguing whether there's many.

[chuckle]

0:05:20 SC: So what do we learn? Let's imagine that the audience has heard the fact that black holes evaporate, but don't know any details, and many of us take it that there is some quantum mechanical lesson here, and in particular, there's information from which the black hole is made, and we're not sure where it goes. So, how do you think about this puzzle, the sort of legacy that Steven Hawking left us?

0:05:42 LS: Right. Okay. So Steven asked a wonderful question. It was a deep question. It was a profound question. Let's not mix it up with the question of whether he answered it correctly. Sometimes questions can be more important and leave a bigger legacy than the attempted answers. And I think that's probably the case with Stephen's legacy. That is, question is almost dominating the areas of physics that I've been interested in for the last 20, 30 years, completely dominating them.

0:06:20 LS: Stephen simply asked a very simple question. He said, "If something falls into a black hole, and the black hole evaporates, almost by definition, something that falls into the black hole cannot get out of the black hole. And so what happened to the information that fell into the black hole?" And we can get into all kinds of questions of what we mean by information, and so forth. But just basically the ability that, in principle, looking at what comes out of the black hole, is it possible to reconstruct or fell in? In principle, given technologies which is way, way, way, way beyond anything we'll likely to ever have, but assume that we have it, and it's physically possible, can one reconstruct or fell into the black hole?

0:07:06 LS: And there was a tension there. The tension had to do with the fact that in basic quantum mechanics, nothing is ever lost, in the sense that if you know the quantum state afterwards, you can reconstruct what the quantum state was before. That's a principle of quantum mechanics. And so, in that sense, nothing can ever get lost. On the other hand, black holes were places where things get lost. When anything falls past the horizon of a black hole, we were brought up to learn that they cannot get out. They're trapped. They're there forever. And so, there was a tension there. Do they or don't they get out?

0:07:48 SC: Right.

0:07:49 LS: Can you reconstruct... To put it in practice, what it meant was when a black hole evaporates, it has evaporation products. Anything that evaporates leaves products coming out. There's a black hole. The products of evaporation of a black hole in principle, can you reassemble them and figure out what fell into the black hole? As simple as that. Stephen said, "No." On the basis that black holes are places where you cannot escape from. And other people, myself included said, "No. You have to be able to because basic quantum mechanics says you have to be able to." Who won? I would say, quantum mechanics won.

[laughter]

0:08:29 SC: So, I wanna bring up, there was a funny little paper by a philosopher, Tim Morton. I don't know if you've read his paper?

0:08:35 LS: No, I don't.

0:08:35 SC: But he makes the following point, that our notion of time is a little bit subtle in general relativity, and in particular, we could imagine calling the universe, both the outside of the black hole and the inside of the black hole, simultaneously. In other words, the universe is disconnected into the interior of the black hole and the exterior of the black hole. And then you could imagine that time just plugs on, and information is not lost in the whole quantum wave function, it's just hidden forever in the black hole like it's a baby universe. Is that a possible resolution that you'd be sympathetic to?

0:09:10 LS: No.

0:09:11 SC: Why not?

0:09:11 LS: The black hole evaporates. It's gone.

0:09:14 SC: It's gone in some slicing of the universe, and sometimes slicing.

0:09:21 LS: Well, okay. In practice in the laboratory, the black hole is gone. There's nothing left, not even a little remnant that tells you there was a black hole there. All that's left is the outgoing Hawking radiation. The principles of quantum mechanics said that, that radiation has to carry the information. Now, can you wiggle and can you find ways to try to inveigh against that? No doubt you can. But I think by now... Your first question had to do about string theory. And I told you that string theory provides us an extremely precise tool, which we can investigate these questions in a mathematical context that we have a lot of confidence in. The answer that comes out of that highly mathematical but precise context is nothing is ever lost from a black hole.

0:10:14 SC: Right. Everything is still there.

0:10:15 LS: So I think this is a solid conclusion. As I said, it's not a small thing. And even Stephen, even Stephen conceded...

0:10:27 SC: He did change his mind eventually, yes. He gave up the past, right? Yeah.

0:10:29 LS: In the end, yeah.

0:10:31 SC: So one way of thinking about it...

0:10:32 LS: Yeah. But he did stick to his guns. He did stick to his guns.

0:10:34 SC: He was a stubborn guy.

0:10:34 LS: A stubborn guy.

0:10:35 SC: But he would change his mind once it became...

0:10:37 LS: He did indeed.

0:10:38 SC: Absolutely clear. So one way that this is often put is, if you throw a book into a black hole, the laws of physics, quantum mechanics say that in principle, you should be able to measure all of the radiation that comes out to reconstruct the book.

0:10:51 LS: Yeah. Measuring is a loaded term in quantum mechanics.

0:10:53 SC: It is.

0:10:53 LS: We have to be careful, but there is a sense in which...

0:10:57 SC: It's in there anyway, whether you can measure it or not. But the information is there.

0:11:02 LS: Yeah, yeah.

0:11:02 SC: So, let's just go through some of these thought experiments. This is after all a thought experiment. Just so the audience knows, we haven't made any black holes and watched them evaporate, right?

0:11:10 LS: Oh, I don't know. No, no we haven't.

0:11:13 SC: Yeah, we have not. So, is it possible that somehow when the book falls into the black hole, its information is duplicated into the outgoing radiation, and we get it that way?

0:11:26 LS: Well, that's an interesting question. Can... One model, one picture of what happens is as information falls into a black hole, it's exactly as you said. It gets duplicated, Xeroxed, let's call it. One copy falls into the black hole, so people who fall into the black hole with the information, see it smoothly pass through the horizon, and the other copy is radiated back out through the Hawking radiation. And then you have... What's it? We have our cake and eat it?

0:12:00 SC: Yeah, we have our cake and eat it too.

0:12:00 LS: We have our cake and eat it too. This is an okay theory, I think. The problem with it is it's known in quantum mechanics that you cannot really duplicate information. That quantum information, true quantum information cannot be duplicated. I thought I'd discovered this fact, and I called it, The no quantum Xerox principle. It had been discovered before by a quantum theorist, and it's called the no-cloning theorem.

0:12:33 SC: Right.

0:12:33 LS: It's one of the most central properties of quantum mechanics, that you can not faithfully reproduce the quantum state, and you can't duplicate it, as you said. So, that left us with a funny situation. You can't even, at least within the usual rules of quantum mechanics, save the situation by duplicating the information. On the other hand, what if you could duplicate the information but nobody could ever in principle detect the fact that you have duplicated the information. Now it get's a little sticky.

0:13:08 SC: Should that make us feel better? Should we care what people can detect?

0:13:11 LS: Yeah, physics is an empirical science and you start getting very... I know I get very troubled when we put mathematical things into a theory that, in principle, can't be detected. I'm not saying you should never do that. I'm not saying that under no circumstances should there be things in a theory which are what's called not empirically confirm-able, but you should be a little bit nervous about it. If you discover that because of the laws of physics that you already trust, that even if you did, let's say, duplicate information, it would be the outcome would always be that you will get frustrated in trying to confirm that you did something bad.

0:14:08 LS: I'll give you an example in a moment. Okay. You might start to worry that you're thinking wrong. So here's the example. Eisenberg taught us a long time ago that you can't know both of the position and the momentum of the position and the velocity of a particle. And you say, "Why not? Why can't you do both?" A particle is just a little thing, if it has a position then it can have a position at two different times. If it has a position at two different times, then it moved from one place to another, how can you not know the velocity at the same time?

0:14:40 SC: That was a good point.

0:14:41 LS: Yeah, it was a good point. And yet it turned out that in quantum mechanics, that no matter how hard you tried to be able to measure both the position and the velocity, doing one would always frustrate the other. And so we came to understand that really there is a conflict, a tension, or whatever you wanna call it, between knowing the position and the velocity of a particle. And that you simply can't do both, you simply can't do both. So best then that your theory not allow it, in principle. Or better yet that the theory never allow an experiment which can say, "Quantum mechanics doesn't say a particle can't have a position and a velocity. It says, nobody can ever detect both of them."

0:15:32 SC: Yeah, okay. As an Everettian I would say there's no such thing as the position or the velocity, there's only the wave function.

0:15:38 LS: You can say it any way you like.

0:15:39 SC: It's the same statement, yes.

0:15:40 LS: But I'll take the view that quantum mechanics doesn't say any such comprehensive thing as that a particle can't have a position and a velocity. What it says is that any experiment to design one will always frustrate the other. So, you ask with a thing falling into a black hole, and so forth, does it get duplicated or it doesn't get duplicated? Supposing you discover that using the rules of quantum mechanics and gravity, you will inevitably discover that any attempt to witness the duplication was always get frustrated. If you measure what's outside, you can't measure what's inside. If you measure what's inside, you can't measure what's outside. Very much like position and velocity. Then maybe you'll say it's a principle similar to the uncertainty principle that you simply can't do both. And that's my feeling about it now.

0:16:31 SC: So the thing that would have been imaginable is we're imagining some literal observer sitting outside the black hole collecting some radiation from it and then diving in really quickly and reading the book inside. You're saying that can't happen.

0:16:44 LS: Well, you can try to do that. Apparently not. Apparently not, it always turns out, again, you always get frustrated. If you wait long enough on the outside to be able to collect this information in the Hawking radiation, you'll always find out that by the time you jump in, the first copy of it, the first clone of it has fallen into the singularity and is gone.

0:17:07 SC: And you can never get there.

0:17:09 LS: Right. And this is, this is not a light-weight statement, this is based on calculation and geometry and so forth. You find out that an attempt to learn both, what fell in and what came out at the same time gets frustrated, it takes too long to learn what came out, so that when you jump in, what went in has gone into the singularity.

0:17:32 SC: Right. And likewise, of course if you just jumped in, you could read the book but then you can...

0:17:36 LS: Can't get out.

0:17:36 SC: Never come back out again, right? Yeah, so you get access to one copy of the book, but never to two.

0:17:42 LS: Yeah the... Yeah, that's what. Yeah. Right.

0:17:44 SC: Yeah, And so, what does this tell us about how we should think about black holes and quantum mechanics?

0:17:50 LS: Well, we should think about black holes and quantum mechanics in a way which is probably not too different than we think about quantum mechanics, that you cannot know everything quantum mechanically which classical physics tells you that you can know. Classical physics tells you, you can know the position and momentum of a particle at the same time. It tells you that you can know the phase, and the energy of an electromagnetic wave. Don't worry if you don't know what all that means, it means something. You can't know both, or at least classical physics says you can know both. Quantum mechanics, you have to be consistent, you have to be very consistent, use quantum mechanics as it was designed to be used and be very skeptical when your rules, when your principles, seem to, how shall I say... I'm running out of words...

0:18:53 SC: To lead you to some contradiction or something?

0:18:54 LS: Yeah, well, certainly when they lead you to a contradiction, then you should be appalled to go back to the drawing board. But when you're using concepts, which in principle by virtue of the rules of the game cannot be confirmed.

0:19:09 SC: Yeah, oh, okay, okay, got that point, yeah. But this does have... This sounds maybe to the people out there like this is an esoteric topic dealing with recovering information from black holes which would be impractical anyway. But there seem to be very deep consequences for the nature of space and time itself. Usually, we think of information being located somewhere in space time...

0:19:33 LS: Yes, yes. That's exactly right.

0:19:33 SC: And this is saying that we shouldn't always ask that question.

0:19:36 LS: Yeah, it's not a good question to ask, where is the information? It may be a good question to ask on a particular way of gathering that information with a particular protocol for detecting that information, where is it that it will be found? But more generally different ways of gathering information may detect, may come to the conclusion, one way would say, it was here. Another way would say, it was there. Without any contradiction, 'cause nobody can do both.

0:20:09 SC: Is there any worry that this way of talking gives so much emphasis to observers that we're being a little bit anthropocentric or something like that, that we are putting agency back into physics?

0:20:20 LS: That, what's the expression, that wagon has already left the stable?

[laughter]

0:20:26 LS: Well, that horse has already left the stable.

0:20:27 SC: Left the stable barn, yes.

0:20:27 LS: Quite a... 1926.

0:20:30 SC: Quantum mechanics.

0:20:31 LS: That was quantum mechanics, right?

0:20:32 SC: Okay, that's very fair. But are you... I mean, we're allowed to get on slight tangents here. When it comes to quantum mechanics, are you a many worlds person or are you agnostic about foundations of QM?

0:20:44 LS: Yeah, I think agnostic is the word.

0:20:47 SC: Agnosticism, okay.

0:20:47 LS: I'll just quote my old friend, Richard Feynman, "This subject is so confusing I can't even tell if there's a problem."

[chuckle]

0:20:58 LS: He was asked exactly the same question, what do you make out of the foundations of quantum mechanics and so forth? And his answer was, "It is so confusing that I can't tell if there's a problem." And I feel that way. Quantum mechanics always works. I expect it will always work. I expect nobody will do an experiment that will violate it. On the other hand, there are some very, very deep and hard... I don't even know that they're hard questions to answer, maybe unanswerable, about the relationship between, let's call it reality, and the mathematical symbols that we use on a piece of paper.

0:21:34 SC: Yeah.

0:21:36 LS: And I share both Feynman's skepticism of whether there's a problem there, and I share Hugh Everett's feelings that you should be able to describe quantum mechanics without collapsing the wave function, etcetera, etcetera. So, one thing I do think is I don't think we will come to the end of the story until we do understand the relation between gravity and quantum mechanics.

0:22:04 SC: Okay, that's interesting, yeah.

0:22:05 LS: Yeah, I just... It's a sense that I have, that too much in quantum mechanics and too much in gravity seem to influence each other and connect to each other in surprising ways, that until we understand that connection, perhaps it's... And also connecting with cosmology, horizons all of these things that maybe until we understand those things better, it's a little bit premature to have a final set of answers about quantum mechanics. But I don't know.

0:22:34 SC: Yeah, okay. Might be a while.

0:22:35 LS: My guess is it's not gonna happen in my lifetime.

0:22:37 SC: I don't know, I'm optimistic, I'm working on it, we're working on it. [chuckle]

0:22:40 LS: Yeah, you're optimistic, I'm 78. [chuckle]

0:22:44 SC: Working hard. Okay, so just to get back to where we are.

0:22:45 LS: Your lifetime, I didn't say your lifetime.

0:22:47 SC: No, I know, but I'm working hard referring to your lifetime. You seem very, very healthy. [chuckle] So we have the situation where we want quantum mechanics to be true and we know some things about black holes. And so this leads us to this relatively profound suggestion, that information doesn't have a unique location in space. And is this basically what you have dubbed, black hole complementarity.

0:23:11 LS: Yes, yes, very much so. Complementarity in the same sense... Nobody could ever figure out what Bohr was talking about incidentally. But to the extent that we do understand what Bohr was talking about, it was complementarity, pretty much in the same sense that information about position and information about momentum are complimentary. You can't have both, you can have one but not the other, and it depends on what experiment you do. So I was trying to use the term in the same way Bohr used it.

0:23:41 SC: And you are lucky enough that Bohr was unclear about how he was using it.

0:23:43 LS: That's right. Bohr was so unclear that anything I said...

0:23:46 SC: You are safe.

0:23:46 LS: Right, right.

0:23:47 SC: And that's closely related to another feature of black holes evaporating that you've also played a major role in, which is the holographic principle. Why are we... So holography somehow asks us to think of the entire black hole as either being or living on or been encoded on the surface, the area around the black hole. So why in the world would anybody think something that crazy?

0:24:12 LS: Well, okay. The reason is the bounds on how much information can be stored in a region of space, and as I'm sure you know, there's a deep set of arguments that began with Bekenstein, Hawking, 't Hooft, myself and so forth, which concluded, mathematically, that the amount of information that can be stored in a region of space cannot be larger than the surface area of the region. Now, that's unusual, because normally in most physics, you would imagine the amount of information, number of bits, that can be stored in a region of space would be proportional to the volume of the region.

0:24:58 SC: Yeah.

0:25:00 LS: That's normal physics. How many?

0:25:02 SC: I am just putting a bit at location in space. What's so hard about that? [chuckle]

0:25:04 LS: Yeah, that's right. Put a every bit of information at every point in space and then your number of bits will be proportional to the volume. Indeed, what's so hard about that? Well, what's so hard about that is you'll wind up putting so much energy into the region of space that you create a black hole, and the black hole will be bigger than the region that you were trying to populate in the first place with information. So, using ideas from black holes, from Hawking, from Bekenstein, and so forth. I think 't Hooft and I both came, somewhat independently, to the conclusion that you, under no circumstances, could you ever put more information into a region of space than its area. Area measured in little Planckian pixels. And once you say that you begin to think, "Well, maybe there should be some theory in which the interior volume of a region should be described by degrees of freedom that live on the boundary."

0:26:06 SC: Can you explain what a degree of freedom is?

0:26:09 LS: Yeah, it's a bit of information.

0:26:10 SC: A bit of information.

0:26:11 LS: A bit of information. Yeah. And I won't try to describe what a bit is.

0:26:15 SC: No that's good. Zero and one. [chuckle]

0:26:17 LS: Zero and one, yeah.

0:26:18 SC: The quantum mechanical version of that.

0:26:20 LS: The quantum mechanical version of zero and one, right. That there should be, if it's absolutely impossible that under any circumstances you can ever contain more than an area's worth of information, again, perhaps that means there should be a description of it in terms of a theory which lives on the boundary. That was called the holographic principle when 't Hooft first said it nobody understood it all. There was a reason.

[chuckle]

0:26:49 LS: No, no. There was a reason. He wrote a paper, that I didn't even know about, and it was called, Dimensional Reduction in Gravity. What he meant was that dimension goes from three dimensions, the volume to the surface area. The word, dimensional reduction, had an entirely different meaning...

[chuckle]

0:27:11 LS: To most physicists, entirely... Don't worry about what it meant, it meant something entirely different. And since I was not in any way interested in dimensional reduction at that time, I'd never even looked at the paper. I didn't even know about it.

0:27:27 SC: Well, this is a lesson for young people out there. You can be one of the world's most famous physicists, but if the names, the titles of your papers are not that enticing, people are not gonna read them.

0:27:36 LS: Yeah, I think that's true. And he was thinking a little bit different than I was, but nevertheless, we came to the same conclusion that the maximum amount of information you could put in a volume was its surface area, and therefore there should be a theory of that type where everything is described by a surface set of degrees of freedom. We call it the hologram. I think he even used the word "hologram" somewheres in his paper. I actually put it in the title, and...

0:28:08 SC: Because a real hologram is a two-dimensional thing that you shine light on.

0:28:10 LS: Yes, yes, a real hologram is a piece of film that's two-dimensional. If you look at it through a microscope all you see is a bunch of random little dots and data, nothing you can make any sense out of, but it encodes full three-dimensional information. So we both independently called it that. I can tell you, when the idea first came out nobody noticed it was 't Hooft at all. They did notice when I wrote it, okay?

0:28:39 SC: The title.

0:28:40 LS: Why? I think I was clearer. I think I was clearer. 't Hooft was a very famous physicist and...

0:28:45 SC: Nobel prize winner, yeah. Helped establish the standard model for particle physics.

0:28:47 LS: Yeah, one of my real heroes.

0:28:50 SC: Yes, absolutely.

0:28:51 LS: Right. So, nobody noticed it. They noticed it when I wrote it. And I think a lot of people said, "Those two guys used to be good physicists, but they've lost their marbles."

[chuckle]

0:29:04 LS: One of the few people who really did get excited about it was Ed Witten. He, from the beginning, caught on to the idea and...

0:29:13 SC: I didn't realize that.

0:29:13 LS: Yeah, yeah. Ed Witten.

0:29:15 SC: Ed Witten, also to those of you who don't know, like one of the most respected physicists around.

0:29:19 LS: Definitely. But the one who really made it precise and made it reputable, let's say, not only reputable, turned it from a wild speculation to a almost clear-cut consequence of quantum mechanics and gravity and eventually to a tool. When a speculation goes from a speculation to a principle and then eventually becomes a tool of the subject then...

0:29:54 SC: That's progress. That's a catalyst. Yeah.

0:29:55 LS: That's progress. That's progress.

0:29:57 SC: And by the, it, we're talking about this idea...

0:30:00 LS: This hologram. This hologram.

0:30:00 SC: That all of this three-dimensional reality can be encoded on the surface.

0:30:03 LS: On the surface area, yeah. That was Juan Maldacena. Juan Maldacena is now one of the very great physicists in the world, and he, again, he did not know about our work. Edward did, Witten did. Maldacena actually did not. He came to it in his own strange way from, actually from String Theory, but the result was the same and he had a very, very precise mathematical version of it. It's the one that we call AdS/CFT now. That's from String Theory, and it was so mathematically precise and so convincing that it became, as I said, a principle and then a tool of physics.

0:30:51 SC: I think this is sufficiently important and central that you should explain AdS/CFT. There's six letters there...

0:30:58 LS: AdS, yeah. Okay.

0:30:58 SC: It's two things. AdS and CFT.

0:31:00 LS: So, AdS is a kind of space time. It's not the space time that we live in in geometry; the geometry of space time. And why is it called AdS, that stands for anti-de Sitter. Now, de Sitter was a physicist, mathematician, physicist from the early parts of the 20th century, who discovered a kind of space called, de Sitter space. I used to joke that his aunt discovered anti-de Sitter space.

[chuckle]

0:31:32 SC: De Sitter was classified actually as an astronomer?

0:31:35 LS: Yeah, yeah. He was an astronomer.

0:31:36 SC: Yeah.

0:31:36 LS: Right. He was an astronomer.

0:31:38 SC: But he solved Einstein's equation for general relativity.

0:31:40 LS: And found the space called, de Sitter space, which is incidentally thought to be the space, the kind of space we really live in.

0:31:48 SC: Yeah, we're getting there.

0:31:49 LS: Right. But we understand that much less than we understand anti-de Sitter space. Now, anti-de Sitter space is, in some sense, the opposite of de Sitter space. It's not really the opposite. It has certain opposite properties. One of them is positive curvature. The other one has negative curvature. It's not like a particle and an anti-particle, if you brought them together they'd disappear. It's just in some sense, anti-de Sitter space has opposite properties to de Sitter space. It turned out that was the one that was most amendable to mathematical analysis.

0:32:25 SC: I think, let me... I'll just interject one little extra piece of information. De Sitter space is characterized by having a positive amount of energy in empty space.

0:32:34 LS: A positive amount of dark energy.

0:32:36 SC: Right.

0:32:37 LS: And maybe you didn't wanna use that term, right? I don't like it either.

0:32:38 SC: I don't care. Dark energy, vacuum energy, whatever it is, but the space itself.

0:32:42 LS: An anti-de Sitter space is the kind that has a negative; dark energy, vacuum energy.

0:32:48 SC: Suffusing all of space. And that's the only thing in the universe, there's no particles, there's no galaxies, there's no dark matter, just vacuum energy everywhere. If it's a positive number, it'll be de Sitter. And negative number, which sounds crazy, and it's certainly not what we have in the world, but the space that you get is anti-de Sitter.

0:33:04 LS: Right. And for reasons which are technical, string theory was very, very comfortable with anti-de Sitter space, and extremely to this day uncomfortable with de Sitter space.

0:33:17 SC: Yes, an ongoing thing like how to reconcile the observed facts that vacuum energy is possible with what string theory says should be the case.

0:33:23 LS: Right. But Maldacena simply took, started with string theory, constructed out of the rules of string theory this anti-de Sitter space and analyzed it. And realized that it had this property that we call the holographic principle. He didn't even know the term, and his paper doesn't even refer to it. Ed Witten was closely related to the string theory, the centers of string theory, who wrote a similar paper, and called it...

0:33:56 SC: Holography.

0:33:57 LS: Holography.

0:33:58 SC: Anti-de Sitter space in holography.

0:34:00 LS: Right. So he was very familiar with my work and he was aware of 't Hooft's work. So reason Juan did not mention it was not because Juan has trouble mentioning other people's work. He just don't know.

0:34:11 SC: No, that's right. So you had, based on black holes, the speculation that somehow the information was encoded on the boundary of the black hole. Maldacena has an example of a specific space-time anti-de Sitter space, where everything that happens in that space time is somehow encoded on a boundary with one lower dimension.

0:34:33 LS: Oh, no, in my work and in 't Hooft's, the black hole was just the starting point. The eventual conclusion is that a region of space, no matter what's in it, black hole or no black hole, would be described by such a boundary theory.

0:34:47 SC: Right.

0:34:48 LS: But we had absolutely no idea how to build that kind of theory, and it really was a speculation. I wouldn't say a wild speculation, because I understood the reasons that we were pushed to it, but it did sound pretty out there. Maldacena's version of essentially the same thing was highly mathematically precise and analyzable with theorem, proof, proof, proof, and...

0:35:23 SC: Equations.

0:35:24 LS: Equations, real equations.

0:35:25 SC: You don't get to speculate as much, 'cause it's equations are governed what you think...

0:35:28 LS: I think the number of equations that appeared in the 't Hooft paper and my paper altogether, a number of relevant equations, both papers had a lot of equations, most of them were irrelevant. The number of equations was very small.

0:35:41 SC: And Maldacena's paper, if I remember correctly, is now the most highly cited paper in theoretical physics.

0:35:47 LS: So I'm told. Right, right, right.

0:35:48 SC: So this is important.

0:35:49 LS: Many thousands...

0:35:50 SC: So good, so Maldacena says, "Look here's at least an example. We have one theory, but there's two different ways of talking about it." These two different ways seem utterly different. One is, there's no gravity, and it's a quantum field theory, and the other is there is gravity, but there's an extra dimension, there's one higher dimension of space. What have we learned from this weird construction?

0:36:15 LS: What do we ever learn? What do we learn? We learn... Okay, I'll tell you what I think we learned. Among other things, many, many things. Gravity does not seem to be a thing that you quantize. I'll tell you what I mean by that. Ordinary theories, like quantum electrodynamics or the theory of harmonic oscillator or the hydrogen atom, the quantum mechanics of those theories was constructed by a recipe. It was a recipe that was invented by Paul Dirac. And it starts with a classical theory, and then you apply some rules to the classical theory called quantization, and you produce a quantum theory of it.

0:37:04 LS: That never worked for gravity. It was the fact that it never worked, no matter how hard you tried, you always ran into infinities or information being lost or something really bad went wrong. It was that, that made people think that there was this tension between quantum mechanics and gravity, and that there was a conflict between them. I think it's turning out the other way. I think the point is that they are so closely connected, so almost the same thing that the idea of quantizing one of them just it separates them too much. It separates them too much from the beginning to say this is classical theory and quantum mechanics. When we put them together, they're just too closely related.

0:37:50 SC: So you're saying, in other words, that other theories you can start classically and then construct this quantum theory but the right way to think about quantum gravity is just to be quantum from the start?

0:38:01 LS: Yes, and more than that, I think almost all quantum systems have features in them which are reminiscent of gravitational things, even though they may have very little to do with.

0:38:15 SC: So we can find echoes of gravity and curved spacetime.

0:38:18 LS: We can find all sorts of echoes of... That's right, of curved spacetime. In ordinary simple quantum mechanical systems. Maldacena's construction was an example of this. Roughly speaking, he said if you could construct a sphere of material, a sphere of material, a shell, where the shell had certain properties that would allow it to be described by certain kinds of quantum mechanical field theories, and shells of matter are described by quantum field theories.

0:38:48 SC: Yup, that we can do.

0:38:50 LS: If we could construct just the right kind, then in every possible way, in the laboratory, in the laboratory, not in outer space, not the... In the laboratory, we could construct the shell. And we could communicate with it by tapping on it, listening to what it does, and so forth, that for all possible purposes, we would discover that what was going on inside contained gravity, even though if we opened up the shell, we will find nothing in it.

[chuckle]

0:39:20 LS: Very weird, very weird.

0:39:24 SC: How close is this to doable?

0:39:27 LS: I think it's getting there. We're not gonna build such shells. That would not be the right thing to do. We will build... Hopefully, we will build quantum computers that can quantum simulate those shells. Quantum simulating means that the actual quantum mechanics that's going on in the quantum computer is a direct reflection of the same quantum mechanics that went on in the shell or in Maldacena's constructions. We'll have these quantum computers. We will be able to interact with them by... We interact with computers. Let me not explaining how we interact with computers.

0:40:08 LS: We interact with them. We make measurements on them. We look at the screen or whatever. What will be going on inside those computers will be pretty much the same as what goes on in a black hole, in a quantum mechanical system that contains gravity. So I think I do believe that in the end we will be able to do a certain class of experiments with quantum computers, whose results, if we took them literally, would say, "You know what's going on inside there? Gravity, black holes, all sorts of things." Even though if we opened up the quantum computer, all we would find would be circuits and...

0:40:51 LS: So what's the endpoint here? What the endpoint is it may turn out that quantum gravity, great theory of gravity, great theory of quantum mechanics, but it might eventually turn into a tool for quantum computational science. It's already going in that direction. It's already very much going in that direction that...

0:41:11 SC: So by that, we mean building a better algorithm for a quantum computer to solve some of the problems?

0:41:15 LS: Possibly building better algorithms, but the one thing that especially comes to mind is building better error correction. Error correction is a big deal in quantum computation.

0:41:28 SC: Let's just back up a bit, 'cause I think this is very valuable. What is a quantum computer and what makes it so great? Why is it better than a classical computer?

0:41:38 LS: It's because quantum mechanics of a given number of qubits. What's a bit? What a bit is a thing... It's a switch which is either on or off.

0:41:46 SC: Zero or one, yeah.

0:41:46 LS: A quantum bit which is called a qubit is a quantum mechanical version of that but it has more... It's a richer thing than a single bit that can be in a superposition of states. Not up and not down but up plus down and so forth.

0:42:01 SC: Combination, yeah.

0:42:02 LS: So a quantum bit is a more complicated thing. Now, quantum bits, a collection of quantum bits, has enormous capacity for what I call, complexity, much more so than the corresponding classical... So the amount of information that you would necessarily have to provide to describe the quantum state of 100 qubits is vast; it's huge. But that also means that that 100 qubits can store an amount of information which is vastly bigger.

0:42:38 SC: A qubit could be encoded in an electron that is spinning clockwise or counterclockwise. So 100 electrons doesn't sound too hard to hang together and rolled into a machine.

0:42:50 LS: 400 electrons, the amount of information that it would take to describe the state of 400 electrons, is as big as the maximum amount of information that could ever be put into our entire observable universe if it was packed as tight as possible.

0:43:06 SC: Right, classical. Right, yeah.

0:43:07 LS: So 400. What's 400? 400 is...

0:43:10 SC: That's nothing.

0:43:10 LS: It's nothing. 400 qubits, in principle, can store that much information. The question is, can you get it out of the computer? And this is... You have to be very, very lucky to design an algorithm where, not only can you store and answer questions involving that much information, but also be able to get it out of the computer.

0:43:34 SC: So people are doing it right now for a couple of qubits at a time, and in very simplified situations, but if we could make it dozens or hundreds, then a world opens up.

0:43:43 LS: A world opens up. And we're not exactly clear, we're really not exactly clear what that world is. We know that there are a handful of problems that we know that are much too hard for classical computers. The buzzword is that they're exponentially hard. Problems which are exponentially hard, which cannot be solved by any reasonable, classical computer, that quantum computers can solve when the quantum computers are built.

0:44:17 LS: There's also another class of problems which are very interesting, which are simulating physical systems, quantum mechanical physical systems. We build into the quantum computer a set of rules, which is analogous to the rules which, let's say, govern a superconductor. And then we can examine in the computer, what happens when you do this, when you do that, you have a lot of control, things that will be too hard to actually do to the superconductor itself. So you get to explore changes, what happens if you change the superconductor a little bit this way, a little bit that way.

0:44:51 SC: This is one of Richard Feynman's original motivation in pioneering quantum computing.

0:44:55 LS: Yeah, yeah, that's right. Absolutely. Absolutely. So that's a world that may open. And there will probably be a wider class of problems that quantum computers can solve. But the problem with quantum computers is because they have so much capacity for complexity, they're also very delicate. Little tiny errors, that wouldn't have any significance at all for a classical bit. A classical bit is like a coin, which is either heads or tails. You put your coin on the table and you sneeze. What happens? Nothing.

0:45:30 SC: Nothing. Pretty robust.

0:45:31 LS: Heads stays heads, it's not susceptible to error because you sneezed. You sneeze on a quantum bit and oh boy.

[chuckle]

0:45:41 SC: You've entangled it now. It's all over.

0:45:43 LS: You've entangled it, you've made a mess out of it. Okay. So that means that you'll have to be extra special in your protection against errors. Errors are random flips of bit, random errors that classical bits are not terribly susceptible to, and quantum bits are very susceptible to. So that means you have to build in redundancy. You have to build into your quantum computer redundancy and error correction, what's called error correction. So that if it happens that an error is made, the computer by itself detects the error and corrects it. Okay, one of the really interesting things that's happened, is that possibly one of the most interesting theoretical constructions about error correction that's happened in the last X years, has come out of thinking about black holes. Remarkable fact. There's a dialogue going on, a very robust dialogue going on, between this kind of gravitational holographic community, called the It from Qubit community.

0:47:00 SC: It from Qubit.

0:47:01 LS: Yeah. It from Qubit community.

0:47:02 SC: Because John Wheeler suggested it from bit, that reality emerged out of information. And you're saying, "Well, he was almost right. It's quantum information."

0:47:09 LS: Right, that's the gravity people, that's the Maldacenas of the world. The Wittens. That's the thing I'm involved in, and so forth. And at the same time, the serious hardcore quantum computer community, which is technological.

0:47:27 SC: They're building things, yeah, they're hardware.

0:47:29 LS: They're building things, right. They're building things with technological purposes in mind. And the two communities are beginning, not only beginning, for the last, I think, probably for about four or five years, five years now, I think there's been a very strong interaction between those two communities with lessons learned from gravity or quantum gravity being transported into the computer science and lessons learned from the computer science transported... I'll give you an example. We have these things in quantum gravity, called wormholes, that connect black holes, that can connect black holes if they're entangled the right way. Okay.

0:48:12 SC: I'm sure our listeners have seen science fiction movies with wormholes in them, yes, Interstellar.

0:48:16 LS: Yeah, okay. Is it possible to send information into one black hole and have it come up the other? We always thought the answer was, no. That that would violate some basic principles, until a few of us started thinking about a phenomena that the quantum computer and the quantum communication community, that's called quantum teleportation. Quantum teleportation is a way of using entangled systems to send messages which are entirely secure and which seem to go from one place to another without passing through the space in between them. We now know that that's the same phenomena as putting a thing into one black hole and having it appear through the coming out the other one.

0:49:02 SC: Okay, but just so that the people who are not experts are grounded here, quantum teleportation we can see in the lab that you can...

0:49:09 LS: You can do it in the lab.

0:49:10 SC: You can do it. Yeah.

0:49:11 LS: You can't see it happen, it goes...

0:49:12 SC: You don't see the poof.

0:49:13 LS: You don't see the information.

0:49:14 SC: But it's a real down to earth.

0:49:17 LS: Oh yeah no, quantum teleportation is a real thing.

0:49:18 SC: 'Cause it sounds a little way out but...

0:49:20 LS: No no no. It is an absolutely real thing. It's hard to do, it's not easy to do, but it has been done and it will be done more and it's considered a technology for ultra-secure communication.

0:49:36 SC: But nothing actually disappears and then re-appears, right? It's information that is teleported, not like the dog.

0:49:43 LS: Yeah, no, it's information that's teleported but you put something in one end and it comes... And an equivalent thing comes out at the other end.

0:49:50 SC: Right. Right.

0:49:52 LS: Right. That's called quantum teleportation, that's a real thing. And we now know that sending things through wormholes is this exact same mathematical phenomenon. You can't use it to send things faster than the speed of light. That doesn't happen.

0:50:07 SC: Still true, yeah.

0:50:08 LS: Still true. And you can't use it to make time machines.

0:50:11 SC: Oh. That's too bad. [chuckle]

0:50:12 LS: Yeah. Yeah. It's too bad. But you can use it for ultra-secure communication which can't be detected by an eavesdropper.

0:50:21 SC: Okay.

0:50:21 LS: In principle, can't be.

0:50:23 SC: And so, you're giving me the impression this is not just a bunch of enthusiastic theoretical physicists saying cool things that they think quantum computer people should care about. You're saying the quantum computer people actually do care about them.

0:50:37 LS: Yeah, and there's a lot of cross-talk, there's a lot of cross-talk. Look, I actually wrote a paper with... Did we actually write the paper together? We did the work together.

0:50:48 SC: Okay.

0:50:50 LS: With a computer scientist, with Scott Aaronson.

0:50:52 SC: Oh yeah, with Scott Aaronson.

0:50:54 LS: Scott Aaronson.

0:50:55 SC: Future Mindscape Podcast guest. He hasn't done it yet.

0:50:56 LS: Right. That is something that if you would have told me 10 years ago I would write a paper with a computer scientist, I would have said, "Hey, you're crazy. I have no interest in that." But much more than that I wrote a paper with him, we talk a lot. Not just Scott and myself, but Dorit Aharanov. A whole world who was devoted to the technology of quantum computation has now come together intellectually, into an intellectual community, which consists of these gravity quantum mechanics people, the quantum information people, the quantum computation, quantum communication. And these are real technologists.

0:51:40 SC: So two questions. I don't wanna forget either one. The first one, let me put myself in the sort of skeptical position here, and wonder about how abstract this all sounds, like here we are, we're in a room, there's chairs, there's tables, and you were saying that secretly it's all a two-dimensional screen of information. [chuckle]

0:52:00 LS: Yeah.

0:52:00 SC: Is that like how secure established robust is that? Or is this a bit of a cross our fingers, hope it's true, kind of thing?

0:52:10 LS: Again, and I'll say it again, the importance of string theory to this community, and to this set of questions is that it provided very, very exact precise examples in which these things are true. Does that mean that they are true of the real world? Not necessarily.

0:52:28 SC: Not necessarily. Okay.

0:52:29 LS: Not necessarily.

0:52:30 SC: But it's plausible that it is, we're just not...

0:52:32 LS: Yeah, it's plausible that it is, but it's a sort of says "Look, the mathematics of this is very, very secure. There's no question that this can happen."

0:52:42 SC: So it's definitely a useful tool.

0:52:44 LS: Right. Now, place where it happens... Yes, it's definitely a useful tool for a number of things. But the place where it happens with precision is in these anti-de Sitter spaces. What do we know about the world we really live in? It's de Sitter space, it's anti-de Sitter's nephew's space.

0:53:01 SC: Right.

0:53:02 LS: And we don't know with the same confidence, we certainly don't know with the same confidence that the rules for de Sitter space are the same. We don't.

0:53:12 SC: So is it possible that at the end of the day all this work ends up being really, really useful for people at Google who are designing algorithms for quantum computers, but doesn't help us understand the nature of space-time? Or...

0:53:24 LS: Do you wanna tell you friends there that we are sitting in the Google office right now?

0:53:28 SC: For people out there in podcast land, we're actually doing this interview in an office at Google X.

0:53:33 LS: Right. Why? Because I consult for...

0:53:35 SC: For some reason Google X thinks that theoretical physicists are really important as senior consultants. So that's evidence for everything you have been saying, right?

0:53:42 LS: Right.

0:53:43 SC: But are computer scientists useful for theoretical physicists? Do you see The Theory of Everything emerging from the clouds here?

0:53:52 LS: Well, I don't know about the Theory for Everything. I've learned a new way to think. In my old age, I'm not very good at it, the computer science way of thinking about things, but a lot of what I think about these days was ideas that were born out of computer science. The most important one of which is called, Complexity Theory, which turned out to have a direct application in the interiors of black holes.

0:54:19 SC: Okay. Complexity in what sense? How does the computer scientist think about complexity?

0:54:24 LS: The complexity, you can think of a complexity of a thing or you can think of a complexity of a process. But, oh, of course, a thing is also a process, a thing is a process, the process of making it from something simple.

0:54:35 SC: Okay. Yeah, fair enough. How do you assemble something?

0:54:40 LS: The definition of computational complexity is the number of minimal simple steps that it takes to go from A to B. So if you're... Let's talk about, I'll give you some examples of complexity. My favorite was always, when I was young, I was interested in theorems. I don't prove theorems anymore.

0:55:01 SC: Yeah.

0:55:01 LS: Right. But I was interested in theorems.

0:55:03 SC: For someone else to do.

0:55:04 LS: I was very curious about the fact that some theorems are hard and some theorems are easy. What's the difference? I mean they're either true or they're false. What's this hard or easy? What does it mean? My teacher, my high school teacher, told me that the four-color map theorem is thought to be very, very hard. I said, "What do you mean hard? It's either true or is not true? Have you make sense of this idea of hard or easy, and I didn't know. Then I later learned that there were theorems that was so hard that they were true. But they were so hard that they couldn't be proved, period. That was Mr. Gödel's invention.

0:55:35 SC: Yeah.

0:55:36 LS: And I got very curious. What does it mean to say that a theorem is harder than another theorem? And it turns out what it means is that it's more complex. What does more complex mean? That the minimal number of steps to be able to prove it. Not the number of steps that some mathematician might have used, but the absolute minimal number of steps, logical operations, starting with the postulates, and using logical operations and/or so forth, that the complexity of a theorem is what the minimal number of steps to prove that theorem is, and it's a hard number. Given a theorem you can say what the complexity of it is? Hard theorems are more complex than easy theorems.

0:56:19 SC: And this is a profound statement, because a hard complex theorem in this sense might be very simple to state.

0:56:25 LS: Yes indeed.

0:56:26 SC: The four-color theorem is very simple to state, but very hard to prove, so that's a different notion of complexity.

0:56:31 LS: And the proofs of it involve books worth of equations, one after another, plus a computer computation. So the number of minimal steps to prove the four-color map theorem is thought to be very large compared to proving... X squared plus Y squared equals E squared. What's that called? Pythagoras.

0:56:49 SC: Pythagoras Theorem, yeah.

0:56:50 LS: Right. Right.

0:56:50 SC: And somehow, this illuminates what's going on in the interior of black holes and...

0:56:55 LS: Right. Okay. So in quantum computation, you can say, supposing I want to do a certain calculation, what's the minimum number of basic unit quantum steps that it would take my quantum computer to carry out the calculation? Minimum. Not the number that you've designed. You may have used a lousy algorithm.

0:57:15 SC: God's number.

0:57:16 LS: Right. What's the absolute minimum? And that's called the complexity of the calculation. A black hole evolving is carrying out a calculation. What does that mean? It just means that it's running, it's...

0:57:32 SC: It's evolving.

0:57:33 LS: It's evolving by...

0:57:34 SC: Its quantum information is evolving, yeah.

0:57:34 LS: That's right. Quantum information is evolving. And one of very exciting things, that for me, was to discover that the computational complexity of the evolution of the black hole had a direct meaning in terms of the volume of the interior of the black hole. That was very exciting to me. Why? I always loved the ideas of complexity theory. I never thought it would come into physics.

[chuckle]

0:58:04 LS: I've been fascinated by black holes, I've been especially interested in their interiors. And to suddenly discover that the growth of the interior of a black hole is a case of growing computational complexity was very exciting. Is it having... It is, again, part of this dialogue between the computer scientists and the physicists doing these kind of gravitational black hole kind of things. And yeah, I expect that that will have some impact.

0:58:34 SC: Yeah. Okay. This is all like cutting edge new stuff, right?

0:58:37 LS: It's very cutting edge.

0:58:38 SC: It hasn't shaken out yet.

0:58:39 LS: And having these two communities, some great thought may come out, some great consequence may come out of this interaction, and it may be impossible for anybody to ever really figure out exactly what the root to the great thought was. "Was it was he said? What is what she said? Was it what the computer scientist said? Was it... " Getting communities like this together in a situation where they really do have common interest and enough common tools to be able to honestly interact, I think has been just very, very exciting.

0:59:15 SC: And it was part of the thrill of theoretical physics, right? That we attack problems from different angles, and when they come together, we know something smells right.

0:59:23 LS: Yeah, that's right. And the other thing which makes you think you're on the right track is when something that you've been thinking about turns out the same mathematics or the same set of principles turn up in some other area, and turn out to be useful in that other area, really, really good stuff usually penetrates into several different directions. Many directions. Not just the directions that it was intended for. And when that happens, you know that there's something good about what you're doing. So that is happening.

1:00:00 LS: It's also entering into what's called, condensed metaphysics. Condensed metaphysics is the physics of materials. Some parts of condensed metaphysics are now very heavily using the mathematics of black holes. Why? Black holes are kind of material. Their horizons... The horizons do things. They have viscosity. They have electrical conductivity. The horizon of a black hole wobbles. It does stuff. And apparently again, it's turned out that the mathematics of the surface of black holes turns out to be very similar to the mathematics of fluids, the mathematics of superconductors, the mathematics of other things. And that mathematics is being transformed back and forth between the two communities. One of the biggest and hottest items in the gravitational subject is something called, the SYK model.

1:00:55 SC: Okay.

1:00:56 LS: The SYK model was first invented by a condensed meta-physicist, by the name of Sachdev.

1:01:03 SC: S.

1:01:04 LS: S. That's S. And Kitaev, who's the K, is also, is a computer, quantum computer scientist.

1:01:10 SC: My Caltech colleague, yes.

1:01:12 LS: They invented this model, or at least Sachdev invented this model to describe a certain class of materials, which are called... What are they called? Lousy conductors?

1:01:23 SC: Yeah, something like that. I don't know.

1:01:24 LS: Crummy conductors.

1:01:25 SC: Yeah.

1:01:25 LS: Yeah. Bad conductors.

1:01:26 SC: Something like that. Things that don't... Not superconductors.

1:01:28 LS: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Right. No, not superconductors.

[chuckle]

1:01:30 SC: The opposite.

1:01:31 LS: Right. And he invented this model for that purpose. It turned out that Kitaev looked at it who was not a gravitational person at all, and realized from the little bit that he knew about black holes, is that this model was describing something like a black hole. And now all the black hole physicists, this is the hottest item now. SYK theory.

[chuckle]

1:01:52 SC: I mean, it helps to be as brilliant as Alexei Kitaev.

1:01:55 LS: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

1:01:55 SC: Just to look at this and go, "Oh, that looks like a black hole." Right?

1:01:58 LS: Right. Right. Right. But think... Yes, that's right. But think about it. It was a material science guy, and a condensed meta-physicist and a quantum computer guy who...

1:02:06 SC: Found the black hole.

1:02:06 LS: Who found the opening, and I think it's a serious opening, for new ideas about black holes.

1:02:12 SC: That is amazing.

1:02:12 LS: So, what can I say?

1:02:13 SC: It's a wonderful synergy going on.

1:02:15 LS: Interesting question. How long will it last? These kind of ideas and these kind of synergies that happen, they have a finite lifetime. They don't last forever. I think this one has probably at least a good 10 or 15 years left in it.

1:02:29 SC: Good. Good advice for the younger people out there, the middle aged people out there.

1:02:31 LS: At least.

1:02:32 SC: Okay.

1:02:32 LS: And it will be part of the textbook subject.

1:02:35 SC: Yeah.

1:02:36 LS: Of course, the subject will move on into other things. And this one will be the domain of older...

1:02:45 SC: Yeah.

1:02:45 LS: Yeah, so we'll see.

1:02:46 SC: Well, let me bring it back to sort of wrap things up, here. Let's bring it back to where we started in string theory, because there's another obvious set of questions about gravity and space time, which are the cosmological questions.

1:02:58 LS: Oh yes.

1:03:00 SC: The universe, and so forth. And you alluded cagily to the idea that we should take seriously things that we can't, even in principle, observe, if they're predicted by our theories. One example of that is the cosmological multiverse, which seems to be part of the string theory story. Do you still think that that's true?

1:03:16 LS: I think so. I even wrote a book about it.

1:03:19 SC: Yeah, The Cosmic Landscape.

1:03:21 LS: Right.

1:03:21 SC: We'll plug that book too.

1:03:23 LS: Yeah. Let me put it this way, I don't think anybody has a better idea for resolving some of the great puzzles of cosmology, the great theoretical puzzles of cosmology. In particular the very, very strange, what are called the fine-tunings, that we seem to see in nature. That parameters are extremely finely adjusted and we don't know why. There's of course, a lot of almost anger at this idea of a multiverse and so forth.

1:03:57 SC: We've both felt it, yes. [chuckle]

1:03:58 LS: Yeah, we both felt it. My answer is always, "Yeah, what do you have that's better?" And the answer is never anybody has anything better. So, it's the best idea we have right now for understanding why the parameters of nature are what they are. We don't have a better idea. And that's about all I would say about it with real conviction. Could it turn out to be wrong? I suppose so, but I don't see how. To say that I think it could turn out to be wrong, is to say that I see some other possibility, and I don't.

1:04:30 SC: And so just to be clear. The "it" in this case is the idea that there are regions of space very far away...

1:04:34 LS: Yes, yes.

1:04:34 SC: Where the local laws of physics look different, that's the multiverse we're thinking about.

1:04:37 LS: Yes. That's right. So it's a package. The idea that the universe is extremely... Some parts of it we know with certainty. We know the universe is much bigger than the part we can see. How can we know that it's much bigger than the part that we can see?

[chuckle]

1:04:51 LS: The same way that we know that the Earth is much bigger than a portion that I can personally see.

1:04:56 SC: Right.

1:04:57 LS: We know it's much bigger, not because we've been around the world, but because we see it's very flat. If we go out in a field, we see it's very flat. We know that it's probably going on for a long distance because it's so flat. It probably doesn't terminate at the place where we see the horizon.

1:05:14 SC: That would be weird. Yes.

1:05:15 LS: Right, right. That would be weird.

1:05:16 SC: And the universe is the same way.

1:05:17 LS: The universe is the same way. It's very flat. It just seems to go on and on, and there's no reason to think it stops at what the horizon is. So how much bigger? At least a thousand times bigger, in volume. So that means there's a potential for lots of stuff out there that might be somewhat unrecognizable to us. More likely it's millions and billions and billions and billions and billions of times bigger. So to say that the only things that are possible, the only kinds of environments, the only kind of behaviors that are possible are the kind that we see in our little tiny patch was presumptuous.

1:05:54 LS: It's entirely possible that the universe is full of different kinds of patches with different kinds of behaviors, just like the Earth is full of different kinds of patches, arctic, jungle, desert, that there could be a great deal going on out there. And so, there may be very many different environments and only a small part of which are habitable. Which are the parts that are un-habited? The parts that are un-habited are parts that are habitable. What does it take to be habitable? Well, possibly some very special numbers.

1:06:32 SC: Numbers for the fundamental constants of nature, parameters, yeah.

1:06:36 LS: For the fundamental... Yeah. Right. So it's not that everywhere in the whole universe is all the same and that we could live anywheres in it. At least according to this idea. There are just a small tiny fraction of the universe which is of a type that is habitable. But where are we? We're in the place which is habitable. It's as dumb as that.

[chuckle]

1:06:57 LS: It doesn't take a heavy philosopher to understand this concept.

1:07:01 SC: And string theory helps us by allowing for all these different laws of physics.

1:07:05 LS: Yeah, right. String theory has many, many different solutions, where "solution" means a possible kind of world, with different parameters, with different numbers. And so, you take these things, the fact that we know the universe is much bigger than it is, than we can see, the fact that the parameters seem to be highly fine-tuned, and the fact that string theory gives more rise to an enormous diversity of different possibilities. Those are the three things that go into this idea. Is it a open and shut game? In other words, is it done? Or has the fat lady sung yet? No, I don't think so. But my usual answer to the critics of it is, "You got anything better buddy?" And the answer's almost always, no.

1:07:50 SC: It seems to me, and maybe I...

1:07:52 LS: No, I take it back. The answer is always, no.

1:07:54 SC: Always, no. So far anyway, yes.

1:07:55 LS: Yeah.

1:07:56 SC: These wonderful ideas we've been discussing about qubits and quantum information and the inversions of space time. It seems to me that they haven't yet attempted to address mostly cosmological questions. What happens at the Big Bang, etcetera.

1:08:09 LS: That's absolutely correct.

1:08:10 SC: Is this an open area?

1:08:11 LS: Yes.

1:08:11 SC: You think is gonna have a lot of interesting things?

1:08:13 LS: Yes, yes. I think it's an open area, and I won't try to predict what the next area will be that will be exciting, because you're usually gonna be wrong. Something will come up that you didn't expect. But just in the natural course of events, if science and if physics is going to answer these questions, it's got to address that question. How do these ideas bits, qubits, strings and all that kind of mathematics, holographic principle, AdS/CFT, or something different, how will they address the cosmological questions? And I think that's unknown.

1:08:50 SC: Right.

1:08:50 LS: It's unknown. Although there are plenty of people who have some ideas and the ideas may be good, I think they certainly haven't reached consensus.

1:09:00 SC: Okay. And so for my really final question then, in addition to helping to reinvent the nature of space and time, and to spending time here at Google X with the quantum computing folks, you've also written several books, right?

1:09:12 LS: Mm-hmm.

1:09:12 SC: Not only straightforwardly popular books, but The Theoretical Minimum...

1:09:15 LS: Yeah.

1:09:16 SC: Series, and there's video lectures. What is the way that you think about your activities in that realm? How important is that to you?

1:09:26 LS: That's an interesting question. I did it for two reasons. One of them was a emotional response of my father, of all things. My father was a very smart man. He was a plumber. He had a fifth grade education. He had a bunch of friends. They were all plumbers rough characters, but they were all intellectuals. This was a long time ago, and...

1:09:51 SC: What part of New York was it? [laughter]

1:09:54 LS: The Bronx. The Bronx. Okay, they'd sit around the table. I would sit... I was a little kid, I would sit around with them, they'd talk about everything. They would talk about history, they would talk about science, all kinds of stuff, and it was a very strange mix of intellectualism and crackpotism. Why crackpotism? It wasn't that they were intrinsically crackpot-y, particular when it came to science, it was that they had no access to be able to know what was real from what was a bit of crackpot science.

1:10:33 LS: Okay. And when I started to get really interested in science, I started to try to teach my father. It worked, I mean, I taught him things, but I always had this emotional sense of that there were all these guys like my father out there I would like to be able to teach them what real science is, so they'd know the difference. The people I met when I got older, that reminded me of a little bit or they were actually scientifically pretty literate people, a lot of the older people that I met in the community in Palo Alto, these were people from everything from computer programmers, to doctors, to things like that, and they were very, very interested in science. They were very interested in physics, and generally older.

1:11:26 LS: And at some point, I decided to try to teach in Stanford's Continuing Studies program. The idea was to teach one quarter and to give them a Scientific American background into some of the modern physics. They loved it. It was extremely popular, the one quarter, and so I went to a second quarter and then a third quarter, but it was intended to be at the level of, let's call it Scientific American. They came to me at some point and they said, "Enough with the Scientific American stuff. Teach us physics."

1:12:00 SC: "Show us the equations."

1:12:00 LS: "Teach us the real things. Show us the equations. Do it right." And so I did. I think I spent 10 or 12 or 13 years, I don't know how long, over and over teaching courses for these people. They weren't courses in the sense of anybody took an exam. They were just me lecturing and then...

1:12:21 SC: As the teacher, that's the fun part. Good, you figured it out. [chuckle]

1:12:23 LS: Yeah, I did. I had all the fun part, and at some point, I decided to take the lecture notes and write them up into books. So that was the origin of The Theoretical Minimum.

1:12:34 SC: Are we done? Is there another volume coming out?

1:12:35 LS: There will be sometime, probably.

1:12:37 SC: Okay, very good, well, I completely agree. I think you're right. I think there's an enormous audience, if we do it well, to explain science, at a pretty good level.

1:12:45 LS: Yeah, yeah, I think it's important to explain in an honest level. And an honest level allows you to use things like metaphors and analogies, but you must explain what is a metaphor, what is an analogy, and you must also explain why it's deficient, 'cause they almost always are.

1:13:03 SC: Yeah. Alright, well, you've done a fantastic job at it.

1:13:07 LS: Good. Thank you.

1:13:07 SC: And I hope the podcast helps sell you some books.

1:13:10 LS: Okay.

1:13:10 SC: Lenny Susskind, thanks so much for being on our podcast.

1:13:12 LS: Good. Okay, thank you, Sean.

[music]

Jackpot! A Lenny as great as the other Lenny, at least.

This is GREAT. Not only content-wise, but also… more NY accents in science please 🙂

Bravo sirs!

Excelente diálogo!

Temas bem desenvolvidos, talvez, gostasse que se tivessem alongado um pouco mais sobre Multiverso cosmologico.

Muito curiosa sobre mecânica quântica, e, adoro ler, saber, informar_me!

Agradeço, Sean, pois, como sempre, conduz qualquer diálogo, de uma forma exemplar!

Agradeço a Sr. Leonard Susskind!

This is embarrassing, but I’m a professional retoucher and huge nerd and got so excited when I saw this episode come up in my feed I started crying at work and had to explain why. THANK YOU!

Thanks Lenny and Sean for a great podcast, close to my heart. I am one of the thousands of middle age people Len has educated over the years. With only high school maths and physics to go by i burrowed through the whole series of The Theoretical Minimum and am much the wiser for it. It has opened up a whole world to me of past and present beautiful minds with wonderful insights into the nature of existence.

Cheers Leonard Susskind