Big Picture Part Six: Caring

One of a series of quick posts on the six sections of my book The Big Picture — Cosmos, Understanding, Essence, Complexity, Thinking, Caring.

Chapters in Part Six, Caring:

- 45. Three Billion Heartbeats

- 46. What Is and What Ought to Be

- 47. Rules and Consequences

- 48. Constructing Goodness

- 49. Listening to the World

- 50. Existential Therapy

In this final section of the book, we take a step back to look at the journey we’ve taken, and ask what it implies for how we should think about our lives. I intentionally kept it short, because I don’t think poetic naturalism has many prescriptive advice to give along these lines. Resisting the temptation to give out a list of “Ten Naturalist Commandments,” I instead offer a list of “Ten Considerations,” things we can keep in mind while we decide for ourselves how we want to live.

A good poetic naturalist should resist the temptation to hand out commandments. “Give someone a fish,” the saying goes, “and you feed them for a day. Teach them to fish, and you feed them for a lifetime.” When it comes to how to lead our lives, poetic naturalism has no fish to give us. It doesn’t even really teach us how to fish. It’s more like poetic naturalism helps us figure out that there are things called “fish,” and perhaps investigate the various possible ways to go about catching them, if that were something we were inclined to do. It’s up to us what strategy we want to take, and what to do with our fish once we’ve caught them.

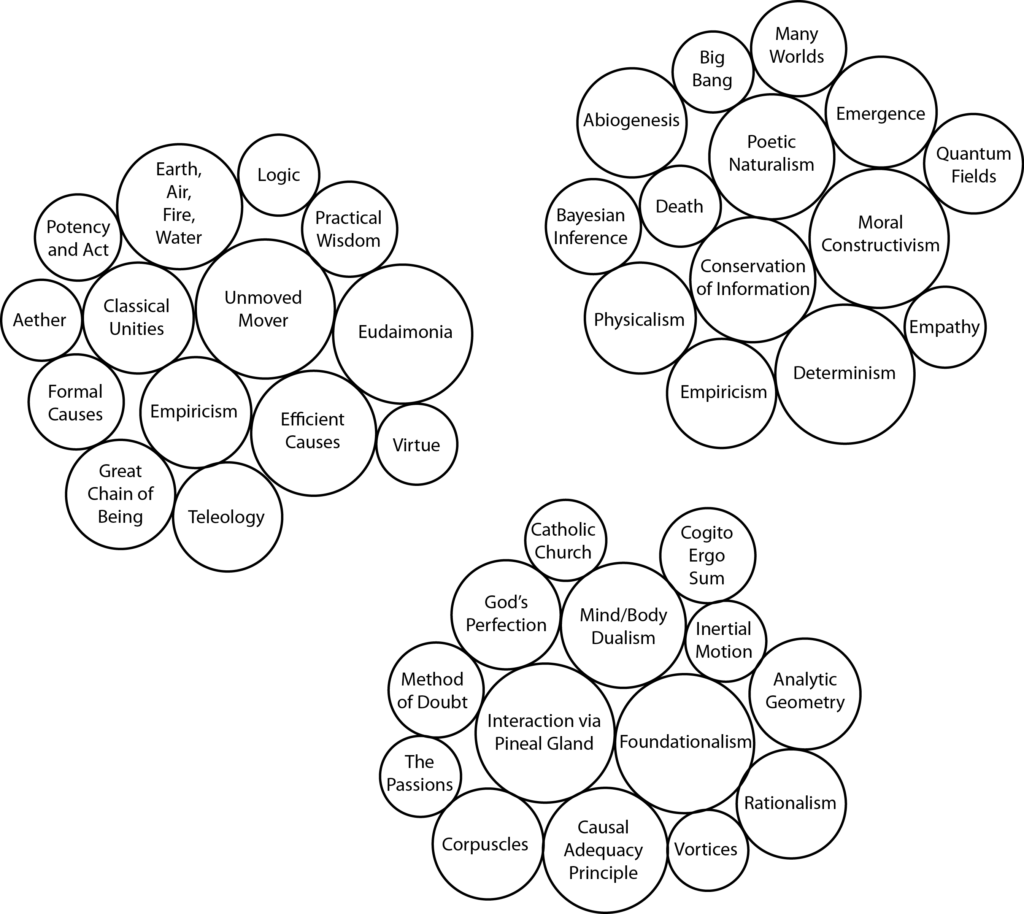

There are nevertheless some things worth saying, because there are a lot of untrue beliefs to which we all tend to cling from time to time. Many (most?) naturalists have trouble letting go of the existence of objective moral truths, even if they claim to accept the idea that the natural world is all that exists. But you can’t derive ought from is, so an honest naturalist will admit that our ethical principles are constructed rather than derived from nature. (In particular, I borrow the idea of “Humean constructivism” from philosopher Sharon Street.) Fortunately, we’re not blank slates, or computers happily idling away; we have aspirations, desires, preferences, and cares. More than enough raw material to construct workable notions of right and wrong, no less valuable for being ultimately subjective.

Of course there are also incorrect beliefs on the religious or non-naturalist side of the ledger, from the existence of divinely-approved ways of being to the promise of judgment and eternal reward for good behavior. Naturalists accept that life is going to come to an end — this life is not a dress rehearsal for something greater, it’s the only performance we get to give. The average person can expect a lifespan of about three billion heartbeats. That’s a goodly number, but far from limitless. We should make the most of each of our heartbeats.

The finitude of life doesn’t imply that it’s meaningless, any more than obeying the laws of physics implies that we can’t find purpose and joy within the natural world. The absence of a God to tell us why we’re here and hand down rules about what is and is not okay doesn’t leave us adrift — it puts the responsibility for constructing meaningful lives back where it always was, in our own hands.

Here’s a story one could imagine telling about the nature of the world. The universe is a miracle. It was created by God as a unique act of love. The splendor of the cosmos, spanning billions of years and countless stars, culminated in the appearance of human beings here on Earth — conscious, aware creatures, unions of soul and body, capable of appreciating and returning God’s love. Our mortal lives are part of a larger span of existence, in which we will continue to participate after our deaths.

It’s an attractive story. You can see why someone would believe it, and work to reconcile it with what science has taught us about the nature of reality. But the evidence points elsewhere.

Here’s a different story. The universe is not a miracle. It simply is, unguided and unsustained, manifesting the patterns of nature with scrupulous regularity. Over billions of years it has evolved naturally, from a state of low entropy toward increasing complexity, and it will eventually wind down to a featureless equilibrium condition. We are the miracle, we human beings. Not a break-the-laws-of-physics kind of miracle; a miracle in that it is wondrous and amazing how such complex, aware, creative, caring creatures could have arisen in perfect accordance with those laws. Our lives are finite, unpredictable, and immeasurably precious. Our emergence has brought meaning and mattering into the world.

That’s a pretty darn good story, too. Demanding in its own way, it may not give us everything we want, but it fits comfortably with everything science has taught us about nature. It bequeaths to us the responsibility and opportunity to make life into what we would have it be.

I do hope people enjoy the book. As I said earlier, I don’t presume to be offering many final answers here. I do think that the basic precepts of naturalism provide a framework for thinking about the world that, given our current state of knowledge, is overwhelmingly likely to be true. But the hard work of understanding the details of how that world works, and how we should shape our lives within it, is something we humans as a species have really only just begun to tackle in a serious way. May our journey of discovery be enlivened by frequent surprises!

Big Picture Part Six: Caring Read More »