Social Entropy

Noah Smith points us to “the derpiest thing ever posted on the internet” — a reflection on the history of empires and the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Strictly speaking, probably not the derpiest thing ever posted; the internet is old, and vast, and strewn with some truly derpy things. But even under a charitable reading: yeah, pretty derpy.

The Second Law — the entropy of isolated systems either remains constant or increases over time — offers an irresistible temptation to the kind of person who might want to take Grand Ideas of Science and apply them to complex social phenomena. (I’m totally that kind of person, so I know how they think.) Entropy is roughly “disorder,” and all we have to do is look out the window/internet to see disorder running rampant all around us. So people from Henry Adams and Oswald Spengler to Thomas Pynchon and Norbert Wiener have suggested (with different degrees of seriousness) that maybe the social chaos around us is merely the inevitable outcome of some grand dynamical principle.

The post in question, at a blog called finem respice that is fond of referring to itself in the third person, takes a slightly different angle than usual. The insight is not that things fall apart and the centre cannot hold, but that things are falling apart faster and faster.

Sadly, long-term, the battle against entropy appears to be a losing one. In weaker moments the always philosophical finem respice reader might be reduced to despondency when realizing that while reading this piece the heat radiated by the brain creates more entropy than the reading creates order. In effect, and with apologies to Jim Morrison, “No one gets out of here cohesively.”

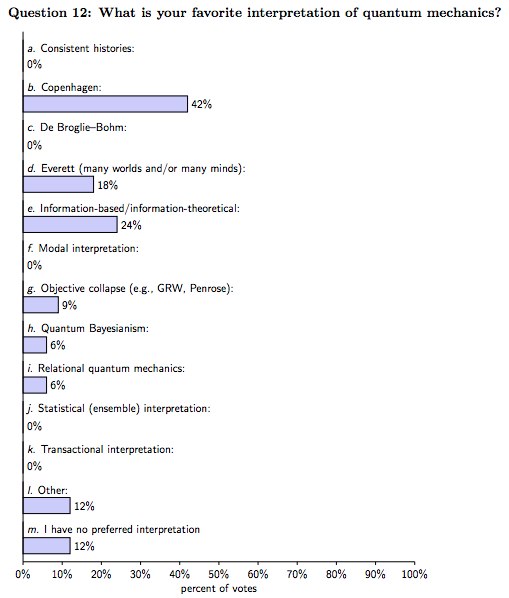

To finem respice‘s way of thinking, there is good reason to believe in “social entropy” as well. Not only this, but its rate of growth seems to be increasing. Of the 50-70 empires that dominate the study of history, it is suddenly striking to realize that, generally speaking, the more modern the empire, the shorter its lifespan.

Sweeping ideas from physics offer wonderful metaphorical inspiration, and even occasional precise insight, into the kinds of messy situations one typically cares about in the humanities and social sciences. Still, a little care is called for, and what we have here is kind of an absence of much care.

The biggest problem is the one that creationists always make: neither the biosphere nor our social environment is anything like a closed system. Yes, the entropy you are generating while reading this blog post is greater than the hoped-for order created by your comprehension of a new text. But that’s true of the universe, not of your brain all by itself. The Earth radiates lots of high-entropy radiation into space, but its own entropy can easily decrease. It’s not just allowed — it happens quite readily. Order is spontaneously generated in subsystems as the larger world increases in entropy. The plain evidence of history would seem to imply that this kind of tendency is especially prominent in the social context. The Roman/Persian/Chinese empires were not actually preceded by even earlier empires that lasted ten times as long. Even aside from the limitations of borrowing ideas from physics and applying them outside their circumscribed domains, this kind of idea would seem to be flatly contradicted by the evidence.

Which is a shame, because there might very well be something interesting to say about the changing cohesiveness of nation-sized institutions over time, and there may even be ideas from physics that could help. It does seem sensible to claim that the pace of all sorts of changes has picked up over the last few hundred years, even if “entropy” isn’t at all the right concept to reach for here. It’s the self-organization part, as well as ideas from complexity and network theory, that can be really helpful. This is the kind of thing that reformed physicist Geoffrey West has been studying with (seemingly) great success.

So it’s not at all derpy to take ideas from physics (or any other field) and let them prod you into new insights in other fields. It’s just doing it in a sloppy way that grates. Derpiness, like entropy, tends to increase, but that doesn’t mean we can’t resist.