What Is Science?

There is an old parable — not sure if it comes from someone famous I should be citing, or whether I read it in some obscure book years ago — about a lexicographer who was tasked with defining the word “taxi.” Thing is, she lived and worked in a country where every single taxi was yellow, and every single non-taxi car was blue. Makes for an extremely simple definition, she concluded: “Taxis are yellow cars.”

Hopefully the problem is obvious. While that definition suffices to demarcate the differences between taxis and non-taxis in that particular country, it doesn’t actually capture the essence of what makes something a taxi at all. The situation was exacerbated when loyal readers of her dictionary visited another country, in which taxis were green. “Outrageous,” they said. “Everyone knows taxis aren’t green. You people are completely wrong.”

The taxis represent Science.

(It’s usually wise not to explain your parables too explicitly; it cuts down on the possibilities of interpretation, which limits the size of your following. Jesus knew better. But as Bob Dylan said in a related context, “You’re not Him.”)

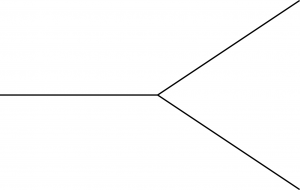

Defining the concept of “science” is a notoriously tricky business. In particular, there is long-running debate over the demarcation problem, which asks where we should draw the line between science and non-science. I won’t be providing any final answers to this question here. But I do believe that we can parcel out the difficulties into certain distinct classes, based on a simple scheme for describing how science works. Essentially, science consists of the following three-part process:

- Think of every possible way the world could be. Label each way an “hypothesis.”

- Look at how the world actually is. Call what you see “data” (or “evidence”).

- Where possible, choose the hypothesis that provides the best fit to the data.

The steps are not necessarily in chronological order; sometimes the data come first, sometimes it’s the hypotheses. This is basically what’s known as the hypothetico-deductive method, although I’m intentionally being more vague because I certainly don’t think this provides a final-answer definition of “science.”

The reason why it’s hard to provide a cut-and-dried definition of “science” is that every one of these three steps is highly problematic in its own way. Number 3 is probably the trickiest; any finite amount of data will generally underdetermine a choice of hypothesis, and we need to rely on imprecise criteria for deciding between theories. (Thomas Kuhn suggested five values that are invoked in making such choices: accuracy, simplicity, consistency, scope, and fruitfulness. A good list, but far short of an objective algorithm.) But even numbers 1 and 2 would require a great deal more thought before they rose to the level of perfect clarity. It’s not easy to describe how we actually formulate hypotheses, nor how we decide which data to collect. (Problems that are vividly narrated in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, among other places.)

But I think it’s a good basic outline. What you very often find, however, are folks who try to be a bit more specific and programmatic in their definition of science, and end up falling into the trap of our poor lexicographic enthusiasts: they mistake the definition for the thing being defined.

Along these lines, you will sometimes hear claims such as these:

- “Science assumes naturalism, and therefore cannot speak about the supernatural.”

- “Scientific theories must make realistically falsifiable predictions.”

- “Science must be based on experiments that are reproducible.”

In each case, you can kind of see why one might like such a claim to be true — they would make our lives simpler in various ways. But each one of these is straightforwardly false. …