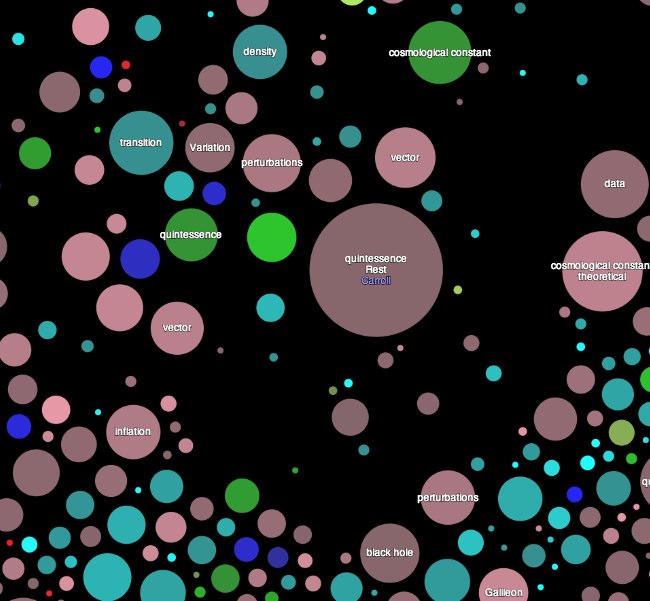

Kim Boddy and I have just written a new paper, with maybe my favorite title ever.

Can the Higgs Boson Save Us From the Menace of the Boltzmann Brains?

Kimberly K. Boddy, Sean M. Carroll

(Submitted on 21 Aug 2013)

The standard ΛCDM model provides an excellent fit to current cosmological observations but suffers from a potentially serious Boltzmann Brain problem. If the universe enters a de Sitter vacuum phase that is truly eternal, there will be a finite temperature in empty space and corresponding thermal fluctuations. Among these fluctuations will be intelligent observers, as well as configurations that reproduce any local region of the current universe to arbitrary precision. We discuss the possibility that the escape from this unacceptable situation may be found in known physics: vacuum instability induced by the Higgs field. Avoiding Boltzmann Brains in a measure-independent way requires a decay timescale of order the current age of the universe, which can be achieved if the top quark pole mass is approximately 178 GeV. Otherwise we must invoke new physics or a particular cosmological measure before we can consider ΛCDM to be an empirical success.

We apply some far-out-sounding ideas to very down-to-Earth physics. Among other things, we’re suggesting that the mass of the top quark might be heavier than most people think, and that our universe will decay in another ten billion years or so. Here’s a somewhat long-winded explanation.

A room full of monkeys, hitting keys randomly on a typewriter, will eventually bang out a perfect copy of Hamlet. Assuming, of course, that their typing is perfectly random, and that it keeps up for a long time. An extremely long time indeed, much longer than the current age of the universe. So this is an amusing thought experiment, not a viable proposal for creating new works of literature (or old ones).

There’s an interesting feature of what these thought-experiment monkeys end up producing. Let’s say you find a monkey who has just typed Act I of Hamlet with perfect fidelity. You might think “aha, here’s when it happens,” and expect Act II to come next. But by the conditions of the experiment, the next thing the monkey types should be perfectly random (by which we mean, chosen from a uniform distribution among all allowed typographical characters), and therefore independent of what has come before. The chances that you will actually get Act II next, just because you got Act I, are extraordinarily tiny. For every one time that your monkeys type Hamlet correctly, they will type it incorrectly an enormous number of times — small errors, large errors, all of the words but in random order, the entire text backwards, some scenes but not others, all of the lines but with different characters assigned to them, and so forth. Given that any one passage matches the original text, it is still overwhelmingly likely that the passages before and after are random nonsense.

That’s the Boltzmann Brain problem in a nutshell. Replace your typing monkeys with a box of atoms at some temperature, and let the atoms randomly bump into each other for an indefinite period of time. Almost all the time they will be in a disordered, high-entropy, equilibrium state. Eventually, just by chance, they will take the form of a smiley face, or Michelangelo’s David, or absolutely any configuration that is compatible with what’s inside the box. If you wait long enough, and your box is sufficiently large, you will get a person, a planet, a galaxy, the whole universe as we now know it. But given that some of the atoms fall into a familiar-looking arrangement, we still expect the rest of the atoms to be completely random. Just because you find a copy of the Mona Lisa, in other words, doesn’t mean that it was actually painted by Leonardo or anyone else; with overwhelming probability it simply coalesced gradually out of random motions. Just because you see what looks like a photograph, there’s no reason to believe it was preceded by an actual event that the photo purports to represent. If the random motions of the atoms create a person with firm memories of the past, all of those memories are overwhelmingly likely to be false.

This thought experiment was originally relevant because Boltzmann himself (and before him Lucretius, Hume, etc.) suggested that our world might be exactly this: a big box of gas, evolving for all eternity, out of which our current low-entropy state emerged as a random fluctuation. As was pointed out by Eddington, Feynman, and others, this idea doesn’t work, for the reasons just stated; given any one bit of universe that you might want to make (a person, a solar system, a galaxy, and exact duplicate of your current self), the rest of the world should still be in a maximum-entropy state, and it clearly is not. This is called the “Boltzmann Brain problem,” because one way of thinking about it is that the vast majority of intelligent observers in the universe should be disembodied brains that have randomly fluctuated out of the surrounding chaos, rather than evolving conventionally from a low-entropy past. That’s not really the point, though; the real problem is that such a fluctuation scenario is cognitively unstable — you can’t simultaneously believe it’s true, and have good reason for believing its true, because it predicts that all the “reasons” you think are so good have just randomly fluctuated into your head!

All of which would seemingly be little more than fodder for scholars of intellectual history, now that we know the universe is not an eternal box of gas. The observable universe, anyway, started a mere 13.8 billion years ago, in a very low-entropy Big Bang. That sounds like a long time, but the time required for random fluctuations to make anything interesting is enormously larger than that. (To make something highly ordered out of something with entropy S, you have to wait for a time of order eS. Since macroscopic objects have more than 1023 particles, S is at least that large. So we’re talking very long times indeed, so long that it doesn’t matter whether you’re measuring in microseconds or billions of years.) Besides, the universe is not a box of gas; it’s expanding and emptying out, right?

Ah, but things are a bit more complicated than that. We now know that the universe is not only expanding, but also accelerating. The simplest explanation for that — not the only one, of course — is that empty space is suffused with a fixed amount of vacuum energy, a.k.a. the cosmological constant. Vacuum energy doesn’t dilute away as the universe expands; there’s nothing in principle from stopping it from lasting forever. So even if the universe is finite in age now, there’s nothing to stop it from lasting indefinitely into the future.

But, you’re thinking, doesn’t the universe get emptier and emptier as it expands, leaving no particles to fluctuate? Only up to a point. A universe with vacuum energy accelerates forever, and as a result we are surrounded by a cosmological horizon — objects that are sufficiently far away can never get to us or even send signals, as the space in between expands too quickly. And, as Stephen Hawking and Gary Gibbons pointed out in the 1970’s, such a cosmology is similar to a black hole: there will be radiation associated with that horizon, with a constant temperature.

In other words, a universe with a cosmological constant is like a box of gas (the size of the horizon) which lasts forever with a fixed temperature. Which means there are random fluctuations. If we wait long enough, some region of the universe will fluctuate into absolutely any configuration of matter compatible with the local laws of physics. Atoms, viruses, people, dragons, what have you. The room you are in right now (or the atmosphere, if you’re outside) will be reconstructed, down to the slightest detail, an infinite number of times in the future. In the overwhelming majority of times that your local environment does get created, the rest of the universe will look like a high-entropy equilibrium state (in this case, empty space with a tiny temperature). All of those copies of you will think they have reliable memories of the past and an accurate picture of what the external world looks like — but they would be wrong. And you could be one of them.

That would be bad. …

The Higgs Boson vs. Boltzmann BrainsRead More »

So I was very pleased when Nature, that well-known literary publication, asked me to review Thomas Pynchon’s new book, Bleeding Edge. Longtime readers of me will know that I’ve been fascinated by Pynchon’s work for a long time now; longtime readers of Pynchon will know that it’s not always easy going (even when it’s consistently rewarding). Fortunately, Bleeding Edge was a delightful page-turner, with the usual colorful characters and many laughs along the way. It’s a detective story set in Manhattan, 2001, as things were falling down: the tech bubble, not to mention the World Trade Center. Because Pynchon seems to enjoy confounding expectations, this is a book with a single definite point-of-view character, as well as an identifiable plot. Because he is nevertheless still Thomas Pynchon, there are multiple strands of interlocking schemes and conspiracies, most of which don’t really get “resolved” in the conventional sense. But some do! It’s a great book, easily recommended either to the committed Pynchon fan or to their skeptical friend would would appreciate a user-friendly introduction.

So I was very pleased when Nature, that well-known literary publication, asked me to review Thomas Pynchon’s new book, Bleeding Edge. Longtime readers of me will know that I’ve been fascinated by Pynchon’s work for a long time now; longtime readers of Pynchon will know that it’s not always easy going (even when it’s consistently rewarding). Fortunately, Bleeding Edge was a delightful page-turner, with the usual colorful characters and many laughs along the way. It’s a detective story set in Manhattan, 2001, as things were falling down: the tech bubble, not to mention the World Trade Center. Because Pynchon seems to enjoy confounding expectations, this is a book with a single definite point-of-view character, as well as an identifiable plot. Because he is nevertheless still Thomas Pynchon, there are multiple strands of interlocking schemes and conspiracies, most of which don’t really get “resolved” in the conventional sense. But some do! It’s a great book, easily recommended either to the committed Pynchon fan or to their skeptical friend would would appreciate a user-friendly introduction.