Where Have We Tested Gravity?

General relativity is a rich theory that makes a wide variety of experimental predictions. It’s been tested many ways, and always seems to pass with flying colors. But there’s always the possibility that a different test in a new regime will reveal some anomalous behavior, which would open the door to a revolution in our understanding of gravity. (I didn’t say it was a likely possibility, but you don’t know until you try.)

Not every experiment tests different things; sometimes one set of observations is done with a novel technique, but is actually just re-examining a physical regime that has already been well-explored. So it’s interesting to have a handle on what regimes we have already tested. For GR, that’s not such an easy question; it’s difficult to compare tests like gravitational redshift, the binary pulsar, and Big Bang nucleosynthesis.

So it’s good to see a new paper that at least takes a stab at putting it all together:

Linking Tests of Gravity On All Scales: from the Strong-Field Regime to Cosmology

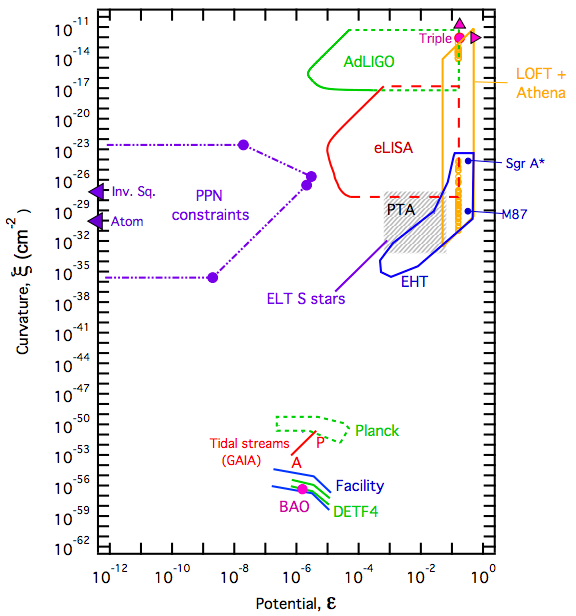

Tessa Baker, Dimitrios Psaltis, Constantinos SkordisThe current effort to test General Relativity employs multiple disparate formalisms for different observables, obscuring the relations between laboratory, astrophysical and cosmological constraints. To remedy this situation, we develop a parameter space for comparing tests of gravity on all scales in the universe. In particular, we present new methods for linking cosmological large-scale structure, the Cosmic Microwave Background and gravitational waves with classic PPN tests of gravity. Diagrams of this gravitational parameter space reveal a noticeable untested regime. The untested window, which separates small-scale systems from the troubled cosmological regime, could potentially hide the onset of corrections to General Relativity.

The idea is to find a simple way of characterizing different tests of GR so that they can be directly compared. This will always be something of an art as well as a science — the metric tensor has ten independent parameters (six of which are physical, given four coordinates we can choose), and there are a lot of ways they can combine together, so there’s little hope of a parameterization that is both easy to grasp and covers all bases.

Still, you can make some reasonable assumptions and see whether you make progress. Baker et al. have defined two parameters: the “Potential” ε, which roughly tells you how deep the gravitational well is, and the “Curvature” ξ, which tells you how strongly the field is changing through space. Again — these are reasonable things to look at, but not really comprehensive. Nevertheless, you can make a nice plot that shows where different experimental constraints lie in your new parameter space.

The nice thing is that there’s a lot of parameter space that is unexplored! You can think of this plot as a finding chart for experimenters who want to dream up new ways to test our best understanding of gravity in new regimes.

One caveat: it would be extremely surprising indeed if gravity didn’t conform to GR in these regimes. The philosophy of effective field theory gives us a very definite expectation for where our theories should break down: on length scales shorter than where we have tested the theory. It would be weird, although certainly not impossible, for a theory of gravity to work with exquisite precision in our Solar System, but break down on the scales of galaxies or cosmology. It’s not impossible, but that fact should weigh heavily in one’s personal Bayesian priors for finding new physics in this kind of regime. Just another way that Nature makes life challenging for we poor human physicists.

Where Have We Tested Gravity? Read More »

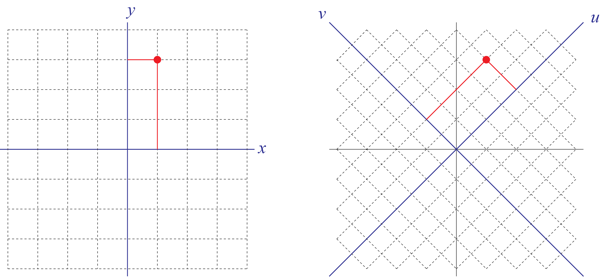

One of the things Kip talks about is that the film refers to the concept of a tesseract, which he thought was fun. A tesseract is a four-dimensional version of a cube; you can’t draw it faithfully in two dimensions, but with a little imagination you can get the idea from the picture on the right. Kip mentions that he first heard of the concept of a tesseract in George Gamow’s classic book

One of the things Kip talks about is that the film refers to the concept of a tesseract, which he thought was fun. A tesseract is a four-dimensional version of a cube; you can’t draw it faithfully in two dimensions, but with a little imagination you can get the idea from the picture on the right. Kip mentions that he first heard of the concept of a tesseract in George Gamow’s classic book