Bookanalia

The annual Los Angeles Times Festival of Books is always a great event, I highly recommend it to anyone in the area. This year’s edition is on April 20-21. I have a special honor, which really should be reserved for someone older and more distinguished but there you have it: I’ll be presenting the prize for science/technology book of the year. The real honor would be to win the prize, but I’ll take what I can get.

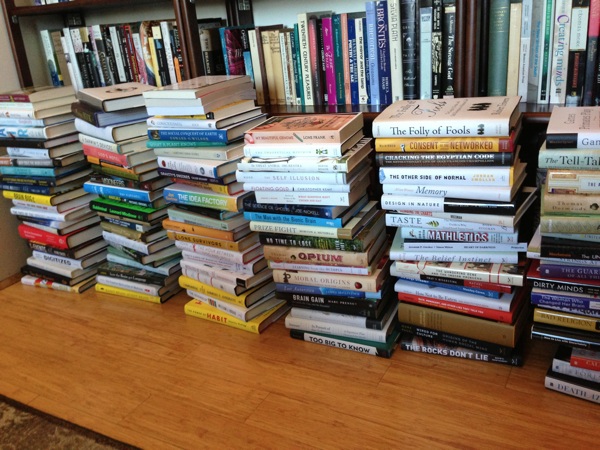

There was no prospect of winning the prize, even though I did write a book, for the sensible reason that my lovely wife was serving on the panel of judges. That’s the bad news; the good news is that, as the spouse of a judge, you benefit from the constant stream of new books arriving on your doorstep. At least you benefit for a little while. Once the number of new science books from the year hits the triple digits, your response is closer to despair. There are a lot of good books out there. Great if you’re a reader, sobering if you’re an author. It’s kind of shocking that anyone found my humble little book at all.

One book I can’t help but mentioning, which I don’t think is eligible for the prize since it came out in 2013 rather than 2012 — The Theoretical Minimum: What You Need to Know to Start Doing Physics, by Leonard Susskind and George Hrabovsky.

Amidst the veritable deluge of science books, Susskind and Hrabovsky have done something simple but radical: they explain introductory physics for real, with all the equations, in a book that is not actually a textbook. This volume (everyone hopes there will be more) covers the principles of classical mechanics, with extraordinary concision but wonderful clarity. The fact that they are trying to explain major concepts rather than cover every detail means they can get much further than a textbook would; a hundred pages in you’re learning about the Principle of Least Action, and not long after that it’s on to Poisson Brackets. If you’re willing to roll up your sleeves and follow the authors along, this is a book from which you can learn a great deal.

Amidst the veritable deluge of science books, Susskind and Hrabovsky have done something simple but radical: they explain introductory physics for real, with all the equations, in a book that is not actually a textbook. This volume (everyone hopes there will be more) covers the principles of classical mechanics, with extraordinary concision but wonderful clarity. The fact that they are trying to explain major concepts rather than cover every detail means they can get much further than a textbook would; a hundred pages in you’re learning about the Principle of Least Action, and not long after that it’s on to Poisson Brackets. If you’re willing to roll up your sleeves and follow the authors along, this is a book from which you can learn a great deal.

This book, needless to say, is not for everybody. But no book is for everybody; the question should be whether there are enough people in the appropriate niche that a book like this might be commercially viable. The answer is a resounding yes, apparently. Released just a few days ago, The Theoretical Minimum zoomed to #4 on the Amazon.com bestseller rankings, which is truly amazing. (The highest I ever got was around #100, but I’m not jealous!)

I wonder if now we’ll see a slew of copycat books that throw conventional wisdom to the wind and try to boost sales by having equations on every page. Perhaps not, but readers would certainly benefit. While I am obviously a firm believer in explaining science to as wide an audience as possible, we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that there is more than one audience out there. Many people might be interested in brushing up on some subject they last took seriously long ago in high school or college, or they might want to fulfill a deferred dream of studying something they regret not taking. The lesson shouldn’t be “equations are okay after all”; it’s “there’s an audience out there for challenging material if it’s presented in an engaging way.”