Why the Many-Worlds Formulation of Quantum Mechanics Is Probably Correct

I have often talked about the Many-Worlds or Everett approach to quantum mechanics — here’s an explanatory video, an excerpt from From Eternity to Here, and slides from a talk. But I don’t think I’ve ever explained as persuasively as possible why I think it’s the right approach. So that’s what I’m going to try to do here. Although to be honest right off the bat, I’m actually going to tackle a slightly easier problem: explaining why the many-worlds approach is not completely insane, and indeed quite natural. The harder part is explaining why it actually works, which I’ll get to in another post.

I have often talked about the Many-Worlds or Everett approach to quantum mechanics — here’s an explanatory video, an excerpt from From Eternity to Here, and slides from a talk. But I don’t think I’ve ever explained as persuasively as possible why I think it’s the right approach. So that’s what I’m going to try to do here. Although to be honest right off the bat, I’m actually going to tackle a slightly easier problem: explaining why the many-worlds approach is not completely insane, and indeed quite natural. The harder part is explaining why it actually works, which I’ll get to in another post.

Any discussion of Everettian quantum mechanics (“EQM”) comes with the baggage of pre-conceived notions. People have heard of it before, and have instinctive reactions to it, in a way that they don’t have to (for example) effective field theory. Hell, there is even an app, universe splitter, that lets you create new universes from your iPhone. (Seriously.) So we need to start by separating the silly objections to EQM from the serious worries.

The basic silly objection is that EQM postulates too many universes. In quantum mechanics, we can’t deterministically predict the outcomes of measurements. In EQM, that is dealt with by saying that every measurement outcome “happens,” but each in a different “universe” or “world.” Say we think of Schrödinger’s Cat: a sealed box inside of which we have a cat in a quantum superposition of “awake” and “asleep.” (No reason to kill the cat unnecessarily.) Textbook quantum mechanics says that opening the box and observing the cat “collapses the wave function” into one of two possible measurement outcomes, awake or asleep. Everett, by contrast, says that the universe splits in two: in one the cat is awake, and in the other the cat is asleep. Once split, the universes go their own ways, never to interact with each other again.

And to many people, that just seems like too much. Why, this objection goes, would you ever think of inventing a huge — perhaps infinite! — number of different universes, just to describe the simple act of quantum measurement? It might be puzzling, but it’s no reason to lose all anchor to reality.

To see why objections along these lines are wrong-headed, let’s first think about classical mechanics rather than quantum mechanics. And let’s start with one universe: some collection of particles and fields and what have you, in some particular arrangement in space. Classical mechanics describes such a universe as a point in phase space — the collection of all positions and velocities of each particle or field.

What if, for some perverse reason, we wanted to describe two copies of such a universe (perhaps with some tiny difference between them, like an awake cat rather than a sleeping one)? We would have to double the size of phase space — create a mathematical structure that is large enough to describe both universes at once. In classical mechanics, then, it’s quite a bit of work to accommodate extra universes, and you better have a good reason to justify putting in that work. (Inflationary cosmology seems to do it, by implicitly assuming that phase space is already infinitely big.)

That is not what happens in quantum mechanics. The capacity for describing multiple universes is automatically there. We don’t have to add anything.

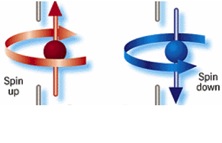

The reason why we can state this with such confidence is because of the fundamental reality of quantum mechanics: the existence of superpositions of different possible measurement outcomes. In classical mechanics, we have certain definite possible states, all of which are directly observable. It will be important for what comes later that the system we consider is microscopic, so let’s consider a spinning particle that can have spin-up or spin-down. (It is directly analogous to Schrödinger’s cat: cat=particle, awake=spin-up, asleep=spin-down.) Classically, the possible states are

The reason why we can state this with such confidence is because of the fundamental reality of quantum mechanics: the existence of superpositions of different possible measurement outcomes. In classical mechanics, we have certain definite possible states, all of which are directly observable. It will be important for what comes later that the system we consider is microscopic, so let’s consider a spinning particle that can have spin-up or spin-down. (It is directly analogous to Schrödinger’s cat: cat=particle, awake=spin-up, asleep=spin-down.) Classically, the possible states are

“spin is up”

or

“spin is down”.

Quantum mechanics says that the state of the particle can be a superposition of both possible measurement outcomes. It’s not that we don’t know whether the spin is up or down; it’s that it’s really in a superposition of both possibilities, at least until we observe it. We can denote such a state like this:

(“spin is up” + “spin is down”).

While classical states are points in phase space, quantum states are “wave functions” that live in something called Hilbert space. Hilbert space is very big — as we will see, it has room for lots of stuff.

To describe measurements, we need to add an observer. It doesn’t need to be a “conscious” observer or anything else that might get Deepak Chopra excited; we just mean a macroscopic measuring apparatus. It could be a living person, but it could just as well be a video camera or even the air in a room. To avoid confusion we’ll just call it the “apparatus.”

In any formulation of quantum mechanics, the apparatus starts in a “ready” state, which is a way of saying “it hasn’t yet looked at the thing it’s going to observe” (i.e., the particle). More specifically, the apparatus is not entangled with the particle; their two states are independent of each other. So the quantum state of the particle+apparatus system starts out like this: …

Why the Many-Worlds Formulation of Quantum Mechanics Is Probably CorrectRead More »

Why the Many-Worlds Formulation of Quantum Mechanics Is Probably Correct Read More »