Good Faith

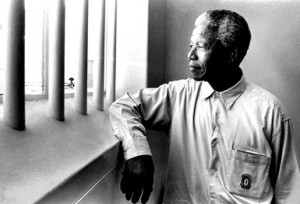

Nelson Mandela was a complicated person. He was no pushover; he was an activist, a revolutionary, someone who got things done and wasn’t afraid to break a few eggs when necessary. But his greatest contribution wasn’t the overthrow of apartheid in South Africa, which arguably would have happened at some point anyway — it was the peaceful way in which the transition happened, and the inclusiveness, forgiveness, and ability to look forward with which he led the nation thereafter.

Nelson Mandela was a complicated person. He was no pushover; he was an activist, a revolutionary, someone who got things done and wasn’t afraid to break a few eggs when necessary. But his greatest contribution wasn’t the overthrow of apartheid in South Africa, which arguably would have happened at some point anyway — it was the peaceful way in which the transition happened, and the inclusiveness, forgiveness, and ability to look forward with which he led the nation thereafter.

Now, the concept of “New Year’s Resolutions” is a pretty awful one. Most people resolve to lose weight or some generic version of being nicer, and most fall off the wagon pretty quickly. A health club I used to go to would display signs in January saying “Regulars: don’t worry about the crowds, most of them will be gone soon.” Not very encouraging, but pretty accurate.

But the idea of resolving to be a better person is a good one, and the beginning of a new year is as good a time as any. So without making an official resolution, this year I’d like to be more like Nelson Mandela.

Not that I’m likely to be lifting any peoples out of oppression or anything so grandiose. My personal stakes are quite a bit lower. But we live in a world where people are constantly disagreeing with each other, taking opposite sides on various issues. And disagreement about important things should be engaged in vociferously; some positions are simply wrong, and sometimes they are wrong in harmful ways. But I want to make more of an effort to treat people I disagree with as fellow human beings, not simply as opponents or enemies. When disagreement occurs, I want to start as much as possible from a position of interpretive charity, imagining that everyone in the conversation is acting in good faith and willing to listen with an open mind. That’s not always the case, but it’s the right default assumption. And it’s one that is really hard to make. There’s an enormous predilection for equating disagreement with bad faith. I disagree with that person, so they are my enemy. It’s an attractive attitude, since I get to imagine that the defense of my beliefs is a lofty moral stance. But giving into that impulse not only sends conversations down a race to the bottom, it weakens my own position. I hold nearly all of my beliefs tentatively, subject to correction in the face of new information or better arguments. To ensure that I have the most accurate beliefs possible, it’s necessary to hear the best objections to them and take them seriously, not take the lazy way out of painting their proponents as bad people.

I have a couple of science/religion debates coming up: with Hans Halvorson at Caltech on January 23, and with William Lane Craig in New Orleans on February 21. These kinds of discussions can get intense, so it’s a good challenge to try to consistently take the high road. My goal isn’t to “win” any debates; it’s to help people understand my point of view, and hopefully even learn something myself.

It’s completely possible that I’m misconstruing what Mandela was all about; I’m no expert. But I figure if he can work with the people who kept him in prison for 27 years, I can speak respectfully with people in public and on the internet. Even if they’re totally wrong (you know who you are).