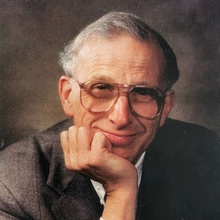

George B. Field, 1929-2024

George Field, brilliant theoretical astrophysicist and truly great human being, passed away on the morning of July 31. He was my Ph.D. thesis advisor and one of my favorite people in the world. I often tell my own students that the two most important people in your life who you will (consensually) choose are your spouse and your Ph.D. advisor. With George, I got incredibly lucky.

I am not the person to recount George’s many accomplishments as a scientist and a scientific citizen. He was a much more mainstream astrophysicist than I ever was, doing foundational work on the physics of the interstellar and intergalactic medium, astrophysical magnetic fields, star formation, thermal instability, accretion disks, and more. One of my favorite pieces of work he did was establishing that you could use spectral lines of hydrogen to determine the temperature of an ambient cosmic radiation field. This was before the discovery of the Cosmic Microwave Background, although George’s method became a popular way of measuring the CMB temperature once it was discovered. (George once told me that he had practically proven that there must be an anisotropic microwave radiation component in the universe, using this kind of reasoning — but his thesis advisor told him it was too speculative, so he never published it.)

At the height of his scientific career, as a professor at Berkeley, along came a unique opportunity: the Harvard College Observatory and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory were considering merging into a single unit, and they needed a visionary leader to be the first director. After some negotiations, George became the founding director of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in 1973. He guided it to great success before stepping down a decade later. During those years he focused more on developing CfA and being a leader in astronomy than on doing research, including leading an influential Decadal Survey in Astronomy for the National Academy of Sciences (the “Field Report”). He never stopped advocating for good science, including in 2016 helping to draft an open letter in support of climate research.

I remember in 1989, when I was still a beginning grad student, hearing that George had just been elected to the National Academy of Sciences. I congratulated him, and he smiled and graciously thanked me. Talking to one of the other local scientists, they expressed surprise that he hadn’t been elected long before, which did indeed seem strange to me. Eventually I learned that he had been elected long before — but turned it down. That is extremely rare, and I wondered why. George explained that it had been a combination of him thinking the Academy hadn’t taken a strong enough stance against the Vietnam War, and that they wouldn’t let in a friend of his for personality reasons rather than scientific ones. By 1989 those reasons had become moot, so he was happy to accept.

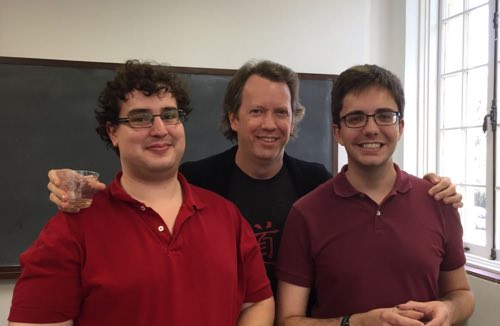

It was complete luck that I ended up with George as my advisor. I was interested in particle physics and gravity, which is really physics more than astronomy, but the Harvard physics department didn’t accept me, while the astronomy department did. Sadly Harvard didn’t have any professors working on those topics, but I was randomly assigned to George as one of the few members of the theory group. Particle physics was not his expertise, but he had noticed that it was becoming important to cosmology, so thought it would be good to learn about it a bit. In typical fashion, he attended a summer school in particle physics as a student — not something most famous senior scientists tend to do. At the school he heard lectures by MIT theorist Roman Jackiw, who at the time was thinking about gravity and electromagnetism in 2+1 spacetime dimensions. This is noticeably different than the 3+1 dimensions in which we actually live — a tiny detail that modern particle theorists have learned to look past, but one that rubbed George’s astrophysicist heart the wrong way. So George wondered whether you could do similar things as in Roman’s theory, but in the real world. Roman said no, because that would violate Lorentz invariance — there would be a preferred frame of reference. Between the two of them they eventually thought to ask, so what if that were actually true? That’s where I arrived on the scene, with very little knowledge but a good amount of enthusiasm and willingness to learn. Eventually we wrote “Limits on a Lorentz- and Parity-Violating Modification of Electrodynamics,” which spelled out the theoretical basis of the idea and also suggested experimental tests, most effectively the prediction of cosmic birefringence (a rotation of the plane of polarization of photons traveling through the universe).

Both George and I were a little dubious that violating Lorentz invariance was the way to make a serious contribution to particle physics. To our surprise, the paper turned out to be quite influential. In retrospect, we had shown how to do something interesting: violate Lorentz invariance by coupling to a field with a Lorentz-violating expectation value in a gauge-invariant way. There turn out to be many other ways to do that, and correspondingly many experimental tests to be investigated. And later I realized that a time-evolving dark energy field could do the same thing — and now there is an ongoing program to search for such an effect. There’s a lesson there: wild ideas are well worth investigating if they can be directly tied to experimental constraints.

Despite being assigned to each other somewhat arbitrarily, George and I hit it off right away (or at least once I stopped being intimidated). He was unmatched in both his pure delight at learning new things about the universe, and his absolute integrity in doing science the right way. Although he was not an expert in quantum field theory or general relativity, he wanted to know more about them, and we learned together. But simply by being an example of what a scientist should be, I learned far more from him. (He once co-taught a cosmology course with Terry Walker, and one day came to class more bedraggled than usual. Terry later explained to us that George had been looking into how to derive the spectrum of the cosmic microwave background, was unsatisfied with the usual treatment, and stayed up all night re-doing it himself.)

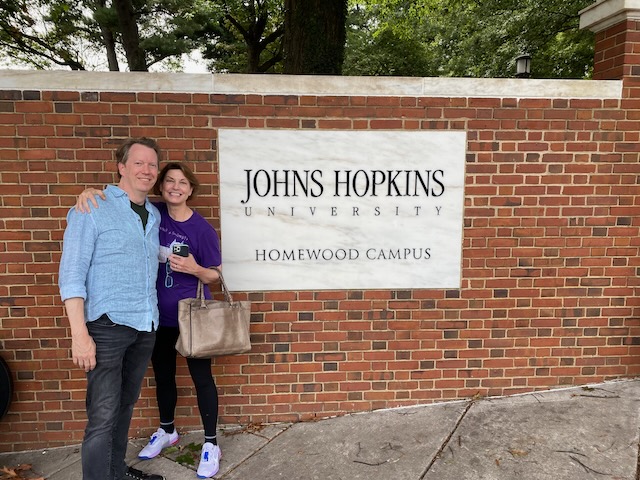

I was also blessed to become George’s personal friend, as well as getting to know his wonderful wife Susan. I would visit them while they were vacationing, and George would have been perfectly happy to talk about science the entire time, but Susan kept us all more grounded. He also had hidden talents. I remember once taking a small rowboat into a lake, but it was extremely windy. Being the younger person (George must have been in his 70s at the time), I gallantly volunteered to do the rowing. But the wind was more persistent than I was, and after a few minutes I began to despair of making much headway. George gently suggested that he give it a try, and bip-bip-bip just like that we were in the middle of the lake. Turns out he had rowed for a crew team as an undergraduate at MIT, and never lost his skills.

George remained passionate about science to the very end, even as his health began to noticeably fail. For the last couple of years we worked hard to finish a paper on axions and cosmic magnetic fields. (The current version is a bit muddled, I need to get our updated version onto the arxiv.) It breaks my heart that we won’t be able to write any more papers together. A tremendous loss.

George B. Field, 1929-2024 Read More »