This is a special guest post by Ian Harry, postdoctoral physicist at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics, Potsdam-Golm. You may have seen stories about a paper that recently appeared, which called into question whether the LIGO gravitational-wave observatory had actually detected signals from inspiralling black holes, as they had claimed. Ian’s post is an informal response to these claims, on behalf of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration. He argues that there are data-analysis issues that render the new paper, by James Creswell et al., incorrect. Happily, there are sufficient online tools that this is a question that interested parties can investigate for themselves. Here’s Ian:

On 13 Jun 2017 a paper appeared on the arXiv titled “On the time lags of the LIGO signals” by Creswell et al. This paper calls into question the 5-sigma detection claim of GW150914 and following detections. In this short response I will refute these claims.

Who am I? I am a member of the LIGO collaboration. I work on the analysis of LIGO data, and for 10 years have been developing searches for compact binary mergers. The conclusions I draw here have been checked by a number of colleagues within the LIGO and Virgo collaborations. We are also in touch with the authors of the article to raise these concerns directly, and plan to write a more formal short paper for submission to the arXiv explaining in more detail the issues I mention below. In the interest of timeliness, and in response to numerous requests from outside of the collaboration, I am sharing these notes in the hope that they will clarify the situation.

In this article I will go into some detail to try to refute the claims of Creswell et al. Let me start though by trying to give a brief overview. In Creswell et al. the authors take LIGO data made available through the LIGO Open Science Data from the Hanford and Livingston observatories and perform a simple Fourier analysis on that data. They find the noise to be correlated as a function of frequency. They also perform a time-domain analysis and claim that there are correlations between the noise in the two observatories, which is present after removing the GW150914 signal from the data. These results are used to cast doubt on the reliability of the GW150914 observation. There are a number of reasons why this conclusion is incorrect: 1. The frequency-domain correlations they are seeing arise from the way they do their FFT on the filtered data. We have managed to demonstrate the same effect with simulated Gaussian noise. 2. LIGO analyses use whitened data when searching for compact binary mergers such as GW150914. When repeating the analysis of Creswell et al. on whitened data these effects are completely absent. 3. Our 5-sigma significance comes from a procedure of repeatedly time-shifting the data, which is not invalidated if correlations of the type described in Creswell et al. are present.

Section II: The curious case of the Fourier phase correlations?

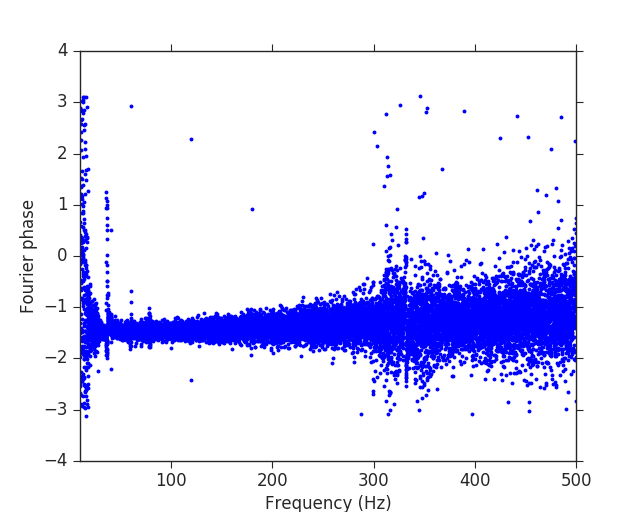

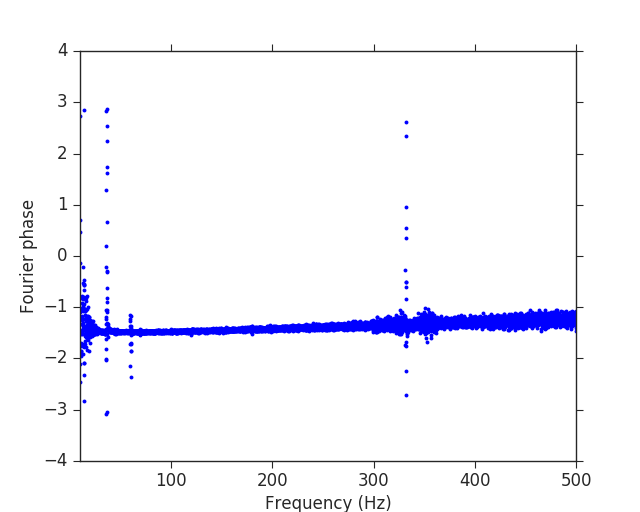

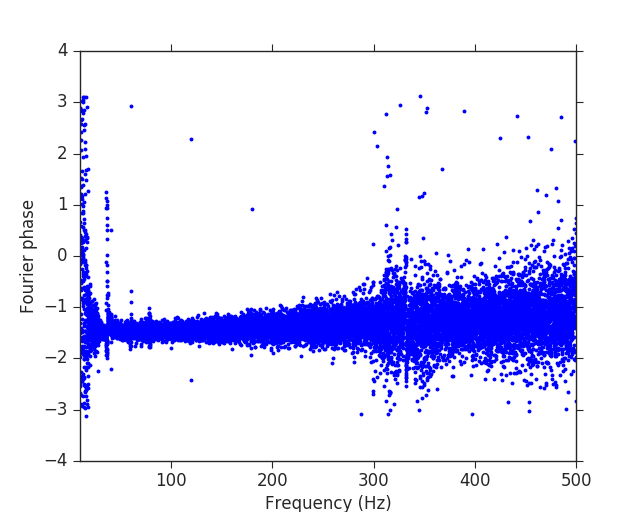

The main result (in my opinion) from section II of Creswell et al. is Figure 3, which shows that, when one takes the Fourier transform of the LIGO data containing GW150914, and plots the Fourier phases as a function of frequency, one can see a clear correlation (ie. all the points line up, especially for the Hanford data). I was able to reproduce this with the LIGO Open Science Center data and a small ipython notebook. I make the ipython notebook available so that the reader can see this, and some additional plots, and reproduce this.

For Gaussian noise we would expect the Fourier phases to be distributed randomly (between -pi and pi). Clearly in the plot shown above, and in Creswell et al., this is not the case. However, the authors overlooked one critical detail here. When you take a Fourier transform of a time series you are implicitly assuming that the data are cyclical (i.e. that the first point is adjacent to the last point). For colored Gaussian noise this assumption will lead to a discontinuity in the data at the two end points, because these data are not causally connected. This discontinuity can be responsible for misleading plots like the one above.

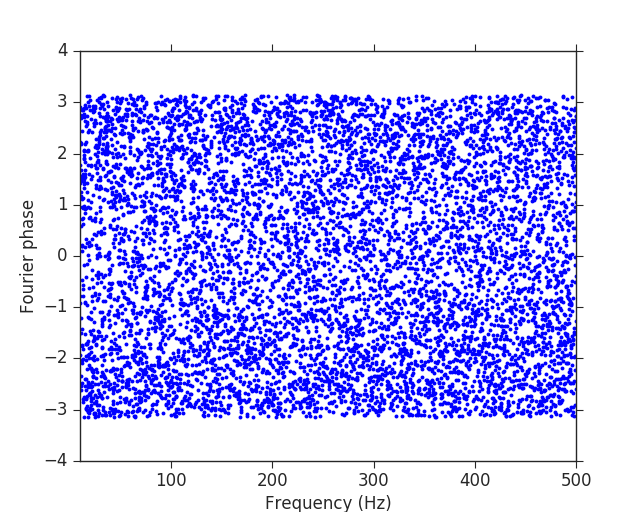

To try to demonstrate this I perform two tests. First I whiten the colored LIGO noise by measuring the power spectral density (see the LOSC example, which I use directly in my ipython notebook, for some background on colored noise and noise power spectral density), then dividing the data in the Fourier domain by the power spectral density, and finally converting back to the time domain. This process will corrupt some data at the edges so after whitening we only consider the middle half of the data. Then we can make the same plot:

And we can see that there are now no correlations visible in the data. For white Gaussian noise there is no correlation between adjacent points, so no discontinuity is introduced when treating the data as cyclical. I therefore assert that Figure 3 of Creswell et al. actually has no meaning when generated using anything other than whitened data.

I would also like to mention that measuring the noise power spectral density of LIGO data can be challenging when the data are non-stationary and include spectral lines (as Creswell et al. point out). Therefore it can be difficult to whiten data in many circumstances. For the Livingston data some of the spectral lines are still clearly present after whitening (using the methods described in the LOSC example), and then mild correlations are present in the resulting plot (see ipython notebook). This is not indicative of any type of non-Gaussianity, but demonstrates that measuring the noise power-spectral density of LIGO noise is difficult, and, especially for parameter inference, a lot of work has been spent on answering this question.

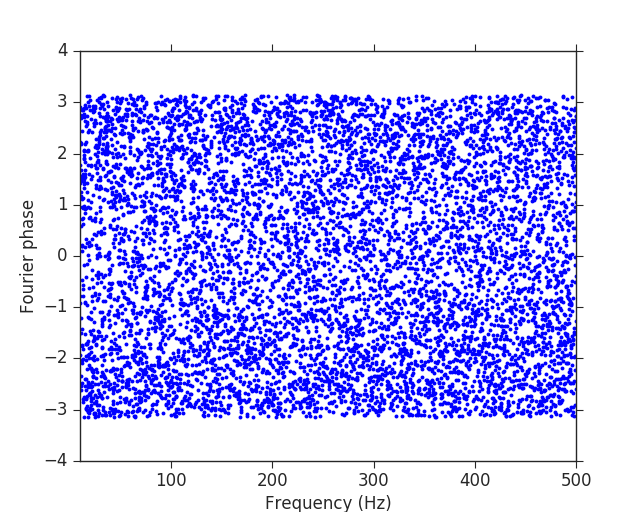

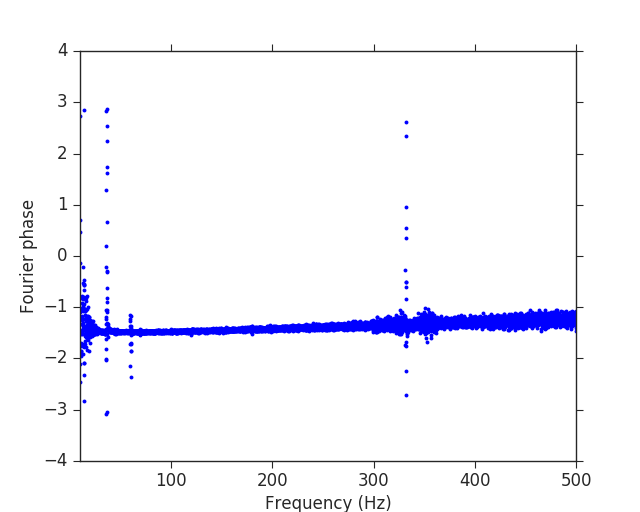

To further illustrate that features like those seen in Figure 3 of Creswell et al. can be seen in known Gaussian noise I perform an additional check (suggested by my colleague Vivien Raymond). I generate a 128 second stretch of white Gaussian noise (using numpy.random.normal) and invert the whitening procedure employed on the LIGO data above to produce 128 seconds of colored Gaussian noise. Now the data, previously random, are ‘colored’ Coloring the data in the manner I did makes the full data set cyclical (the last point is correlated with the first) so taking the Fourier transform of the complete data set, I see the expected random distribution of phases (again, see the ipython notebook). However, If I select 32s from the middle of this data, introducing a discontinuity as I mention above, I can produce the following plot:

In other words, I can produce an even more extremely correlated example than on the real data, with actual Gaussian noise.

Section III: The data is strongly correlated even after removing the signal

The second half of Creswell et al. explores correlations between the data taken from Hanford and Livingston around GW150914. For me, the main conclusion here is communicated in Figure 7, where Creswell et al. claim that even after removal of the GW150914 best-fit waveform there is still correlation in the data between the two observatories. This is a result I have not been able to reproduce. Nevertheless, if such a correlation were present it would suggest that we have not perfectly subtracted the real signal from the data, which would not invalidate any detection claim. There could be any number of reasons for this, for example the fact that our best-fit waveform will not exactly match what is in the data as we cannot measure all parameters with infinite precision. There might also be some deviations because the waveform models we used, while very good, are only approximations to the real signal (LIGO put out a paper quantifying this possibility). Such deviations might also be indicative of a subtle deviation from general relativity. These are of course things that LIGO is very interested in pursuing, and we have published a paper exploring potential deviations from general relativity (finding no evidence for that), which includes looking for a residual signal in the data after subtraction of the waveform (and again finding no evidence for that).

Finally, LIGO runs “unmodelled” searches, which do not search for specific signals, but instead look for any coherent non-Gaussian behaviour in the observatories. These searches actually were the first to find GW150914, and did so with remarkably consistent parameters to the modelled searches, something which we would not expect to be true if the modelled searches are “missing” some parts of the signal.

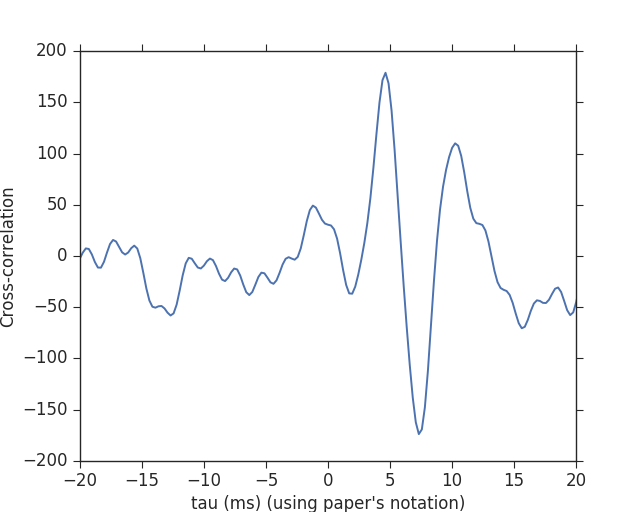

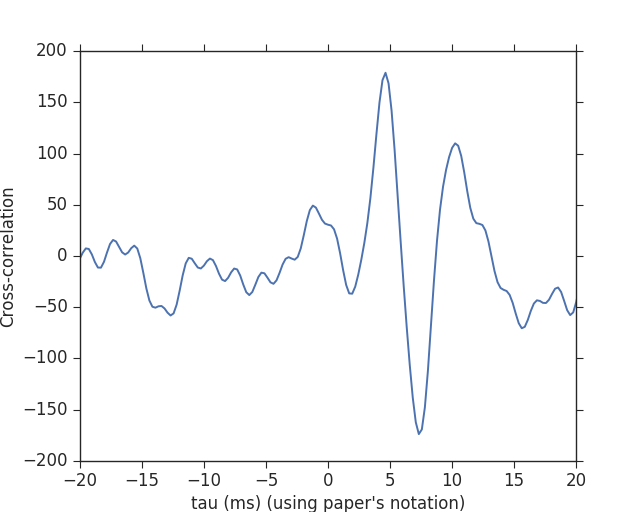

With that all said I try to reproduce Figure 7. First I begin by cross-correlating the Hanford and Livingston data, after whitening and band-passing, in a very narrow 0.02s window around GW150914. This produces the following:

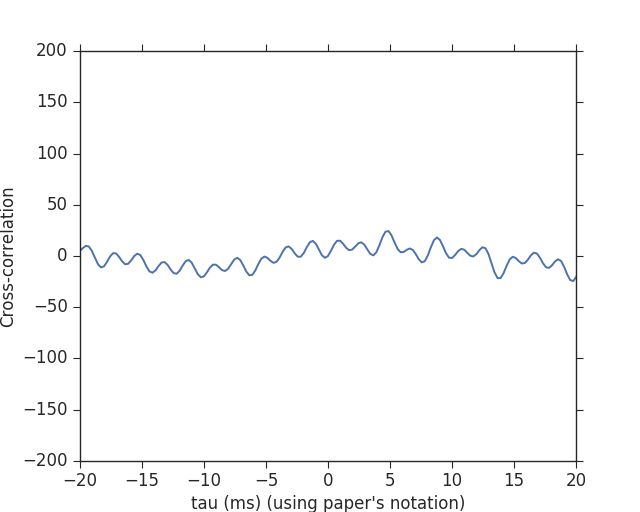

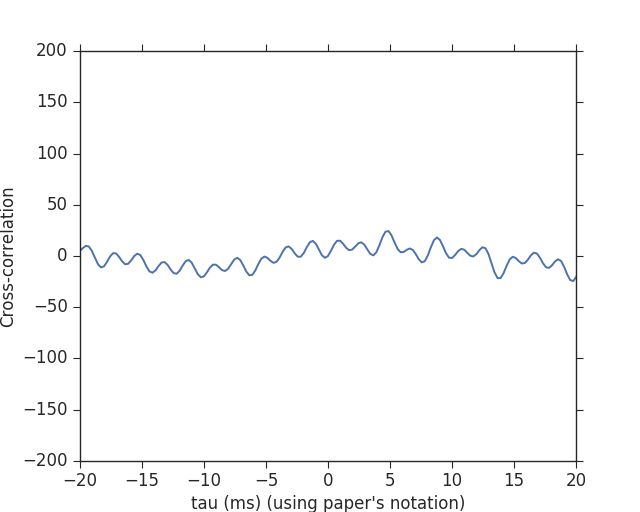

There is a clear spike here at 7ms (which is GW150914), with some expected “ringing” behaviour around this point. This is a much less powerful method to extract the signal than matched-filtering, but it is completely signal independent, and illustrates how loud GW150914 is. Creswell et al. however, do not discuss their normalization of this cross-correlation, or how likely a deviation like this is to occur from noise alone. Such a study would be needed before stating that this is significant—In this case we know this signal is significant from other, more powerful, tests of the data. Then I repeat this but after having removed the best-fit waveform from the data in both observatories (using only products made available in the LOSC example notebooks). This gives:

This shows nothing interesting at all.

Section IV: Why would such correlations not invalidate the LIGO detections?

Creswell et al. claim that correlations between the Hanford and Livingston data, which in their results appear to be maximized around the time delay reported for GW150914, raised questions on the integrity of the detection. They do not. The authors claim early on in their article that LIGO data analysis assumes that the data are Gaussian, independent and stationary. In fact, we know that LIGO data are neither Gaussian nor stationary and if one reads through the technical paper accompanying the detection PRL, you can read about the many tests we run to try to distinguish between non-Gaussianities in our data and real signals. But in doing such tests, we raise an important question: “If you see something loud, how can you be sure it is not some chance instrumental artifact, which somehow was missed in the various tests that you do”. Because of this we have to be very careful when assessing the significance (in terms of sigmas—or the p-value, to use the correct term). We assess the significance using a process called time-shifts. We first look through all our data to look for loud events within the 10ms time-window corresponding to the light travel time between the two observatories. Then we look again. Except the second time we look we shift ALL of the data from Livingston by 0.1s. This delay is much larger than the light travel time so if we see any interesting “events” now they cannot be genuine astrophysical events, but must be some noise transient. We then repeat this process with a 0.2s delay, 0.3s delay and so on up to time delays on the order of weeks long. In this way we’ve conducted of order 10 million experiments. For the case of GW150914 the signal in the non-time shifted data was louder than any event we saw in any of the time-shifted runs—all 10 million of them. In fact, it was still a lot louder than any event in the time-shifted runs as well. Therefore we can say that this is a 1-in-10-million event, without making any assumptions at all about our noise. Except one. The assumption is that the analysis with Livingston data shifted by e.g. 8s (or any of the other time shifts) is equivalent to the analysis with the Livingston data not shifted at all. Or, in other words, we assume that there is nothing special about the non-time shifted analysis (other than it might contain real signals!). As well as the technical papers, this is also described in the science summary that accompanied the GW150914 PRL.

Nothing in the paper “On the time lags of the LIGO signals” suggests that the non-time shifted analysis is special. The claimed correlations between the two detectors due to resonance and calibration lines in the data would be present also in the time-shifted analyses—The calibration lines are repetitive lines, and so if correlated in the non-time shift analyses, they will also be correlated in the time-shift analyses as well. I should also note that potential correlated noise sources was explored in another of the companion papers to the GW150914 PRL. Therefore, taking the results of this paper at face value, I see nothing that calls into question the “integrity” of the GW150914 detection.

Section V: Wrapping up

I have tried to reproduce the results quoted in “On the time lags of the LIGO signals”. I find the claims of section 2 are due to an issue in how the data is Fourier transformed, and do not reproduce the correlations claimed in section 3. Even if taking the results at face value, it would not affect the 5-sigma confidence associated with GW150914. Nevertheless I am in contact with the authors and we will try to understand these discrepancies.

For people interested in trying to explore LIGO data, check out the LIGO Open Science Center tutorials. As someone who was involved in the internal review of the LOSC data products it is rewarding to see these materials being used. It is true that these tutorials are intended as an introduction to LIGO data analysis, and do not accurately reflect many of the intricacies of these studies. For the interested reader a number of technical papers, for example this one, accompany the main PRL and within this paper and its references you can find all the nitty-gritty about how our analyses work. Finally, the PyCBC analysis toolkit, which was used to obtain the 5-sigma confidence, and of which I am one of the primary developers, is available open-source on git-hub. There are instructions here and also a number of examples that illustrate a number of aspects of our data analysis methods.

This article was circulated in the LIGO-Virgo Public Outreach and Education mailing list before being made public, and I am grateful to comments and feedback from: Christopher Berry, Ofek Birnholtz, Alessandra Buonanno, Gregg Harry, Martin Hendry, Daniel Hoak, Daniel Holz, David Keitel, Andrew Lundgren, Harald Pfeiffer, Vivien Raymond, Jocelyn Read and David Shoemaker.

Nicole Yunger Halpern is a theoretical physicist at Caltech’s Institute for Quantum Information and Matter (IQIM). She blends quantum information theory with thermodynamics and applies the combination across science, including to condensed matter; black-hole physics; and atomic, molecular, and optical physics. She writes for Quantum Frontiers, the IQIM blog, every month.

Nicole Yunger Halpern is a theoretical physicist at Caltech’s Institute for Quantum Information and Matter (IQIM). She blends quantum information theory with thermodynamics and applies the combination across science, including to condensed matter; black-hole physics; and atomic, molecular, and optical physics. She writes for Quantum Frontiers, the IQIM blog, every month.

If you’re reading this you probably know about the

If you’re reading this you probably know about the