Big Picture Part Two: Understanding

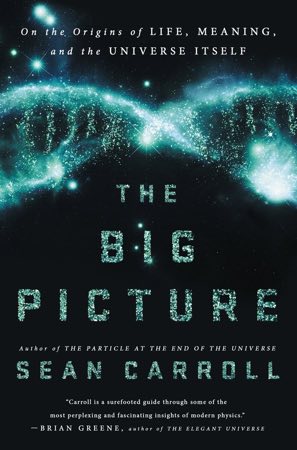

One of a series of quick posts on the six sections of my book The Big Picture — Cosmos, Understanding, Essence, Complexity, Thinking, Caring.

Chapters in Part Two, Understanding:

- 9. Learning About the World

- 10. Updating Our Knowledge

- 11. Is It Okay to Doubt Everything?

- 12. Reality Emerges

- 13. What Exists, and What Is Illusion?

- 14. Planets of Belief

- 15. Accepting Uncertainty

- 16. What Can We Know About the Universe Without Looking at It?

- 17. Who Am I?

- 18. Abducting God

If, as a naturalist, you want to seriously engage with people who might not agree with you already, you’re going to have to talk a bit about epistemology — how we know what we know. It’s common for non-naturalists to level the accusation (perhaps sincerely felt) that naturalists simply assume their conclusion, and use methodologies that are not sensitive to the possibility of something outside the natural world.

I don’t agree, so in The Big Picture I spend a decent amount of time talking about how we actually go about the task of understanding the world. In particular, science doesn’t presume naturalism, it concludes that it’s the best explanation for the world we experience. Provisionally, of course — science never “proves” anything in the logical sense, so we should always be open to changing our minds in the face of new evidence. I talk a good deal (maybe too much) about Bayesian reasoning and how to update our beliefs.

As an extremely simple — but usefully illustrative — example of this philosophy in action, I concocted a straw-man example of theory choice:

Simplicity is sometimes easy to gauge, sometimes it is less so. Consider three competing theories. One says that the motion of planets and moons in the Solar System is governed, at least to a pretty good approximation, by Isaac Newton’s theories of gravity and motion. Another says that Newtonian physics doesn’t apply at all, and that instead every celestial body has an angel assigned to it, and these angels guide the planets and moons in their motions through space, along paths that just coincidentally match those that Newton would have predicted.

Most of us would probably think that the first theory is simpler than the second — you get the same predictions out, without needing to invoke vaguely-defined angelic entities. But the third theory is that Newtonian gravity is responsible for the motions of everything in the Solar System except for the Moon, which is guided by an angel, and that angel simply chooses to follow the trajectory that would have been predicted by Newton. It is fairly uncontroversial to say that, whatever your opinion about the first two theories, the third theory is certainly less simple than either of them. It involves all of the machinery of both, without any discernible difference in empirical predictions. We are therefore justified in assigning it a very low prior credence. (This example seems frivolous, but analogous moves become common when we start talking about the progress of biological evolution or the nature of consciousness.)

Some people don’t like the Bayesian emphasis on priors, because they seem subjective rather than objective. And that’s right — they are. It can’t be helped; we have to start somewhere. On the other hand, ideally the likelihoods of making certain observations can be objectively determined. If you have a certain theory about the world, and that theory is precise and well-defined, you can say with confidence what the chances are of observing various bits of data under the assumption that your theory is correct. In realistic circumstances, we are often stuck trying to evaluate theories that aren’t so rigorously defined in the first place. (“Consciousness transcends the physical” is a legitimate proposition, but it’s not sufficiently precise to make quantitative predictions.) Nevertheless, it’s our job to try to make our propositions as well-defined as possible, to the point where we can use them to objectively establish the likelihoods of different observations.

Everyone’s entitled to their own priors, but not to their own likelihoods.

Sadly, as much as we might aspire to be, we humans are not always completely rational. One concept I talk about is that of a “planet of belief” — rather than grounding our beliefs on an unshakeable foundation, we assemble a collection of beliefs that hold together under a mutual epistemological attraction. That’s not a mistake, it’s the best we can do. The secret is not to grow so attached to our planets that we equip them with impregnable defense systems, so that they can never be altered no matter what new things we learn.

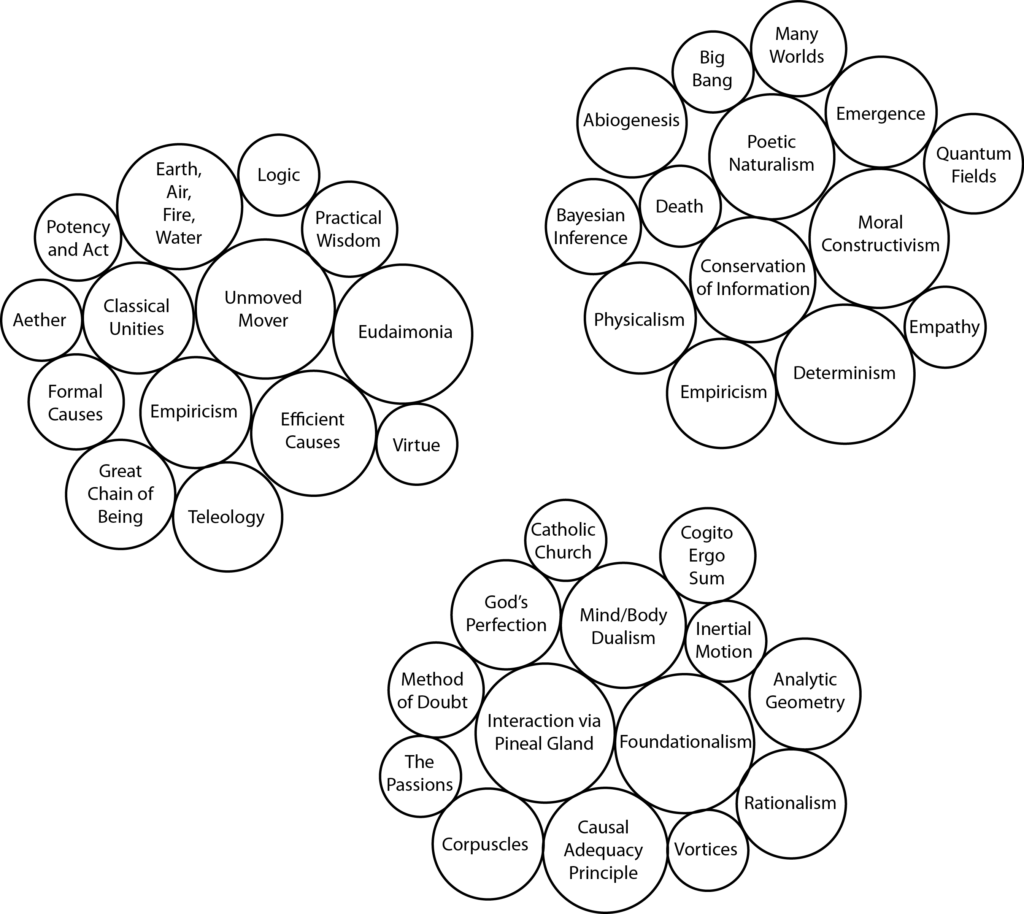

Here we see some representative components of three plausible planets of belief. Can you figure out what kind of person each might belong to?

Big Picture Part Two: Understanding Read More »