One of a series of quick posts on the six sections of my book The Big Picture — Cosmos, Understanding, Essence, Complexity, Thinking, Caring.

Chapters in Part Five, Thinking:

- 37. Crawling Into Consciousness

- 38. The Babbling Brain

- 39. What Thinks?

- 40. The Hard Problem

- 41. Zombies and Stories

- 42. Are Photons Conscious?

- 43. What Acts on What?

- 44. Freedom to Choose

Even many people who willingly describe themselves as naturalists — who agree that there is only the natural world, obeying laws of physics — are brought up short by the nature of consciousness, or the mind-body problem. David Chalmers famously distinguished between the “Easy Problems” of consciousness, which include functional and operational questions like “How does seeing an object relate to our mental image of that object?”, and the “Hard Problem.” The Hard Problem is the nature of qualia, the subjective experiences associated with conscious events. “Seeing red” is part of the Easy Problem, “experiencing the redness of red” is part of the Hard Problem. No matter how well we might someday understand the connectivity of neurons or the laws of physics governing the particles and forces of which our brains are made, how can collections of such cells or particles ever be said to have an experience of “what it is like” to feel something?

These questions have been debated to death, and I don’t have anything especially novel to contribute to discussions of how the brain works. What I can do is suggest that (1) the emergence of concepts like “thinking” and “experiencing” and “consciousness” as useful ways of talking about macroscopic collections of matter should be no more surprising than the emergence of concepts like “temperature” and “pressure”; and (2) our understanding of those underlying laws of physics is so incredibly solid and well-established that there should be an enormous presumption against modifying them in some important way just to account for a phenomenon (consciousness) which is admittedly one of the most subtle and complex things we’ve ever encountered in the world.

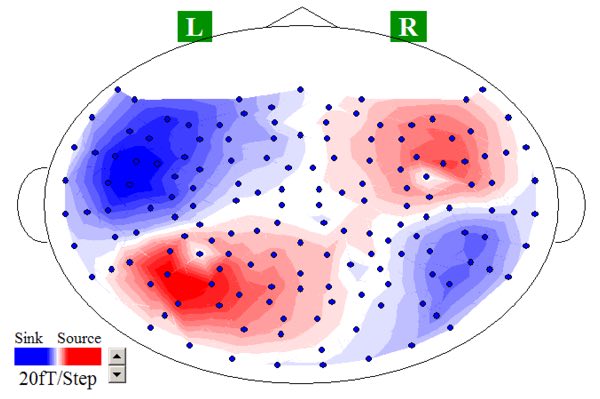

My suspicion is that the Hard Problem won’t be “solved,” it will just gradually fade away as we understand more and more about how the brain actually does work. I love this image of the magnetic fields generated in my brain as neurons squirt out charged particles, evidence of thoughts careening around my gray matter. (Taken by an MEG machine in David Poeppel’s lab at NYU.) It’s not evidence of anything surprising — not even the most devoted mind-body dualist is reluctant to admit that things happen in the brain while you are thinking — but it’s a vivid illustration of how closely our mental processes are associated with the particles and forces of elementary physics.

The divide between those who doubt that physical concepts can account for subjective experience and those who are think it can is difficult to bridge precisely because of the word “subjective” — there are no external, measurable quantities we can point to that might help resolve the issue. In the book I highlight this gap by imagining a dialogue between someone who believes in the existence of distinct mental properties (M) and a poetic naturalist (P) who thinks that such properties are a way of talking about physical reality:

M: I grant you that, when I am feeling some particular sensation, it is inevitably accompanied by some particular thing happening in my brain — a “neural correlate of consciousness.” What I deny is that one of my subjective experiences simply is such an occurrence in my brain. There’s more to it than that. I also have a feeling of what it is like to have that experience.

P: What I’m suggesting is that the statement “I have a feeling…” is simply a way of talking about those signals appearing in your brain. There is one way of talking that speaks a vocabulary of neurons and synapses and so forth, and another way that speaks of people and their experiences. And there is a map between these ways: when the neurons do a certain thing, the person feels a certain way. And that’s all there is.

M: Except that it’s manifestly not all there is! Because if it were, I wouldn’t have any conscious experiences at all. Atoms don’t have experiences. You can give a functional explanation of what’s going on, which will correctly account for how I actually behave, but such an explanation will always leave out the subjective aspect.

P: Why? I’m not “leaving out” the subjective aspect, I’m suggesting that all of this talk of our inner experiences is a very useful way of bundling up the collective behavior of a complex collection of atoms. Individual atoms don’t have experiences, but macroscopic agglomerations of them might very well, without invoking any additional ingredients.

M: No they won’t. No matter how many non-feeling atoms you pile together, they will never start having experiences.

P: Yes they will.

M: No they won’t.

P: Yes they will.

I imagine that close analogues of this conversation have happened countless times, and are likely to continue for a while into the future.

I’m not playing a childish game. You provided a definition, I provided an example which satisfies the definition. You have not provided grounds for refuting my example. There is a cipher for the random number generator where it is doing arithmetic and there are outputs which contain arithmetic encoding Peano’s axioms. You can’t deny this, you haven’t even tried to. Clearly you have a more specific definition in your mind than the one you’ve provided because you’ve provided no other grounds to reject my example. If you bow out of this discussion as you promise, it’s not because I’m being childish, it’s because you refuse to examine somebody else using your definition in a way you didn’t intend. There’s nothing illogical about my usage. A cipher exists, if you’re familiar with Godel’s proof of his incompleteness theorem you know this is true. Whether you or I think it’s a model is immaterial, somebody does and I’m asking you if it matters who says it’s a model or not. You’ve refused to answer that question for 4 posts now and somehow maintain you have the high ground in this discussion. I don’t care who has the high ground, either you’re my peer or somebody too concerned with ego to grant peership to a fellow discussant.

Daniel

Check out this paper: I must admit, best attempt at a purely mechanistic account of consciousness I’ve read so far!

“We recently proposed the attention schema theory, a novel way to explain the brain basis of subjective awareness in a mechanistic and scientifically testable manner. The theory begins with attention, the process by which signals compete for the brain’s limited computing resources. This internal signal competition is partly under a bottom–up influence and partly under top–down control. We propose that the top–down control of attention is improved when the brain has access to a simplified model of attention itself. The brain therefore constructs a schematic model of the process of attention, the ‘attention schema,’ in much the same way that it constructs a schematic model of the body, the ‘body schema.’ The content of this internal model leads a brain to conclude that it has a subjective experience.”

“The attention schema theory: a mechanistic account of subjective awareness” (Web, Graziano)

http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00500/full

Yes, zarzuelazen — and you’ll note that what they describe is exactly the same thing I’ve been proposing — that parts of the brain analytically mirror the brain’s own analyses.

b&

Attention schema makes sense as a mechanism in the same sense that stating the Godel sentence G in a language is not actually self-referencing, you need to take the arithmoquine of the sentence G in order to actually have it refer to itself. This model of being aware of paying attention to an object is consistent with mathematical self-reference where awareness is similar to arithmoquines while the free variable(s) inside arithmoquine would be like the objects of attention. I would argue it’s still just self-reference unless you have some kind of restriction on the semantics that realize such self-reference. A computer that self-references its ability to self-represent is not self-aware unless it interprets its own task in that way. If it doesn’t “know” its task, it can’t possibly be self-aware. This is a step forward but it is just a mechanical explanation. I wouldn’t call it “awareness” in and of itself, it isn’t sufficient though I agree it’s probably necessary.

Daniel

Then you’re faced either with the insurmountable task of explaining why attention schema are insufficient to explain awareness of non-self, or else your standards are inconsistent.

b&

I don’t know what you’re asking. What do you mean by non-self?

Daniel

The non-self would be everything that’s not the self — the “outside” world.

Does attention schema get you to your awareness of that tiger stalking you in the grass? Not your own awareness of your awareness. Rather, is attention schema sufficient to explain the stimulus / response cycles associated with, for example, predator / prey (and other) interactions? Can it explain why you wait for the tiger to look away before you make a run for it?

When replying remember the evolutionary history of those interactions, with extant species of any level of complexity representing a continuum from segmented worms to squid to gazelles to wasps, and much less variation in nervous systems than one might naively expect.

All those other species demonstrate awareness of their environment to one extent or another; deny this and you do great violence to the English language. Whatever that awareness is, however it functions, whatever its origins or most efficient adaptations or limitations…turn it on itself, analyzing the presumed thoughts and motivations of the individual the same way it attempts to predict those of other individuals in the environment.

If that’s not self-awareness, then what else could it possibly be?

b&

In my language that would just be normal reference or representation, not awareness of the external. The attention schema could replace “awareness” with “model” or “representation” and it would still hold. Using “awareness” brings a lot of assumptions to the table. As the authors are using it in regards to people/organisms it makes sense to bring that baggage with the term. However when applying it to machines or things where we can’t assume consciousness a priori, we can’t call it awareness because awareness/consciousness still remains to be proven. It’s circular logic if you assume any computation of something else is aware of that something else and you conclude a system that analyzes itself is thus self-aware. Such a machine/thing can represent and reference a non-self, but that doesn’t mean said model is aware of the non-self.

I feel you perceive my “contradiction” is that I allow awareness of non-self but not awareness of self for attention scheme. That’s not at all my assumption. I’m assuming that I have no idea if the given system is aware or not of anything in the first place. If it satisfies the attention schema my probability assignments to aware vs. not aware are not changed all that much. Maybe in a Bayesian analysis I would increase the probability of awareness simply due to the number of systems (organisms) that satisfy it and I already do call aware, but that’s due to statistical inference from what I would label as similar systems, not a logical deduction of the mechanisms involved.

Daniel