One of a series of quick posts on the six sections of my book The Big Picture — Cosmos, Understanding, Essence, Complexity, Thinking, Caring.

Chapters in Part Five, Thinking:

- 37. Crawling Into Consciousness

- 38. The Babbling Brain

- 39. What Thinks?

- 40. The Hard Problem

- 41. Zombies and Stories

- 42. Are Photons Conscious?

- 43. What Acts on What?

- 44. Freedom to Choose

Even many people who willingly describe themselves as naturalists — who agree that there is only the natural world, obeying laws of physics — are brought up short by the nature of consciousness, or the mind-body problem. David Chalmers famously distinguished between the “Easy Problems” of consciousness, which include functional and operational questions like “How does seeing an object relate to our mental image of that object?”, and the “Hard Problem.” The Hard Problem is the nature of qualia, the subjective experiences associated with conscious events. “Seeing red” is part of the Easy Problem, “experiencing the redness of red” is part of the Hard Problem. No matter how well we might someday understand the connectivity of neurons or the laws of physics governing the particles and forces of which our brains are made, how can collections of such cells or particles ever be said to have an experience of “what it is like” to feel something?

These questions have been debated to death, and I don’t have anything especially novel to contribute to discussions of how the brain works. What I can do is suggest that (1) the emergence of concepts like “thinking” and “experiencing” and “consciousness” as useful ways of talking about macroscopic collections of matter should be no more surprising than the emergence of concepts like “temperature” and “pressure”; and (2) our understanding of those underlying laws of physics is so incredibly solid and well-established that there should be an enormous presumption against modifying them in some important way just to account for a phenomenon (consciousness) which is admittedly one of the most subtle and complex things we’ve ever encountered in the world.

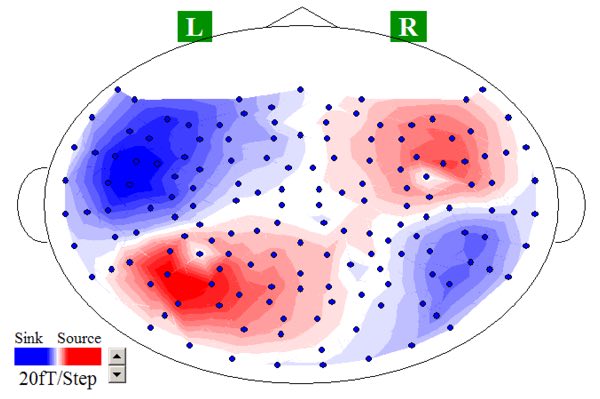

My suspicion is that the Hard Problem won’t be “solved,” it will just gradually fade away as we understand more and more about how the brain actually does work. I love this image of the magnetic fields generated in my brain as neurons squirt out charged particles, evidence of thoughts careening around my gray matter. (Taken by an MEG machine in David Poeppel’s lab at NYU.) It’s not evidence of anything surprising — not even the most devoted mind-body dualist is reluctant to admit that things happen in the brain while you are thinking — but it’s a vivid illustration of how closely our mental processes are associated with the particles and forces of elementary physics.

The divide between those who doubt that physical concepts can account for subjective experience and those who are think it can is difficult to bridge precisely because of the word “subjective” — there are no external, measurable quantities we can point to that might help resolve the issue. In the book I highlight this gap by imagining a dialogue between someone who believes in the existence of distinct mental properties (M) and a poetic naturalist (P) who thinks that such properties are a way of talking about physical reality:

M: I grant you that, when I am feeling some particular sensation, it is inevitably accompanied by some particular thing happening in my brain — a “neural correlate of consciousness.” What I deny is that one of my subjective experiences simply is such an occurrence in my brain. There’s more to it than that. I also have a feeling of what it is like to have that experience.

P: What I’m suggesting is that the statement “I have a feeling…” is simply a way of talking about those signals appearing in your brain. There is one way of talking that speaks a vocabulary of neurons and synapses and so forth, and another way that speaks of people and their experiences. And there is a map between these ways: when the neurons do a certain thing, the person feels a certain way. And that’s all there is.

M: Except that it’s manifestly not all there is! Because if it were, I wouldn’t have any conscious experiences at all. Atoms don’t have experiences. You can give a functional explanation of what’s going on, which will correctly account for how I actually behave, but such an explanation will always leave out the subjective aspect.

P: Why? I’m not “leaving out” the subjective aspect, I’m suggesting that all of this talk of our inner experiences is a very useful way of bundling up the collective behavior of a complex collection of atoms. Individual atoms don’t have experiences, but macroscopic agglomerations of them might very well, without invoking any additional ingredients.

M: No they won’t. No matter how many non-feeling atoms you pile together, they will never start having experiences.

P: Yes they will.

M: No they won’t.

P: Yes they will.

I imagine that close analogues of this conversation have happened countless times, and are likely to continue for a while into the future.

Daniel,

For the overwhelming majority of human history, the biggest question in science was, “Where does the Sun go at night?”

Imagine I was somebody trapped in that mindset, challenging you to provide an explanation. You might start by making offhand references to heliocentricism, and, perhaps, eventually give an introductory description of the geometry of the Solar System. If I insisted that you hadn’t plotted a course on my map for how to reach the land where the Sun goes at night, you might describe NASA rocket probes. If I objected that that was silly or incoherent because everybody knows that the Sun goes down at night, not up, you’d really get exasperated.

Or, for a more likely modern example, imagine me as a Creationist demanding to know why, if Man evolved from monkeys, are there still monkeys? You might reply with a description of common descent, identifying monkeys as our cousins. But if my retort was that I ain’t no monkey’s uncle, you’d wonder what the point of the conversation really was.

Now, also imagine that, along the way, I had embraced unreason and poo-poohed science.

So, were to I continue this discussion with you, I’d have to get into color adaptation models, scotopic vision, dichromacy, and an awful lot more, all in the hopes that I could somehow get through to you that your “qualia” totem is simply incoherent and has absolutely no bearing whatsoever on reality.

But I’m not sure I have the patience for that, and I certainly don’t have the time, and this emphatically isn’t the place.

So, you have a choice. You can take it from somebody who’s devoted many years of study to color science that we have a complete understanding of the subject, one in which “qualia” isn’t a part because it doesn’t fit and doesn’t even make sense in the first place; or you can trot away as the Creationists do feeling smugly superior at having stumped another of those know-it-all scientismists.

Cheers,

b&

zarzuelazen,

Any form of Platonism is trivially demonstrated worng, incoherent, or useless.

The ancient form of Platonism, and the one still held to by Christians today, is essentially that there actually does exist, somehow, in some realm, perfect idealizations of various entities. It could be the perfect square, or the perfect rabbit…or, in the case of Christians, Adam as the perfect body and Jesus as the perfect soul. (See, for example, 1 Corinthians 15 for a lengthy discourse on that topic.) And Earthly entities are but imperfect realizations of the perfect models, with some sort of cosmic force binding the everyday world to the heavenly perfection.

But we know that no such force exists, and Evolution demonstrates specific plasticity incompatible with the theory.

Some modern mathematical Platonists try to claim that the math is the reality, and what we experience is just a shadowy expression of the math. The easiest way to demonstrate the incoherence of such propositions is to invite said Platonists to take a long walk off a short pier.

There are those who claim that math exists as its own entity in some ideal Platonic realm, and that we somehow communicate with this realm. You seem like you might fall into this camp. But it falls to the same problem as the Christian one. For anything in the Platonic realm to influence anything in the real world, there must be an exchange of matter or energy…and we know that doesn’t happen.

In reality, math is simply a very powerful language that’s superbly effective at describing the world. The useless Platonists would say that the map of math is a perfect map of reality and so, by the identity principle, they’re the same…but this adds nothing, and we can understand reality just as well without this addition.

It might help to realize that even “pure” math, such as geometry, started out as empirical science. The Pythagorean Theorem isn’t a^2 + b^2 + c^2, but, rather, that the sums of the areas of squares drawn on the short sides of a right triangle are equal to the area of a square drawn on the long side — and you can be certain that that’s something originally discovered empirically. It’s also something that’s only true empirically in flat geometries such as ours appears to us at human scales. Indeed, if we inhabited the Quantum realm, it wouldn’t even occur to us that 1 + 1 = 2 is some sort of hard-and-fast “fact.”

So…sorry, but Platonism is bunk. Leave it to the poets, and maybe even wax poetically Platonically from time to time as you listen to an Earth, Wind, and Fire album…but don’t get too caught up in thinking that there’s any “there” there.

Cheers,

b&

This is again, not analogous. Neither are the other examples you’ve provided. Every example you cite has the same structure. You provide a theory and your hypothetical opponent cites a failure of that theory due either to incomplete data or inability to contextualize the data within the model. That’s not the type of question I’m asking. Feel free to go into the detail necessary to explain why my icon for red is my sensation of redness. I’ll shoot down the concepts you’ve listed right now so you don’t have to waste your time on them:

Color adaptation models describes only how our processing of an image preserves color properties under changes of illumination and color contexts. This does not describe the sensation of those colors under those conditions.

Scotopic vision explains why low lighting conditions are inadequate for color recognition (though from my understanding the effect is mostly due to the pigment that is reactive under low light conditions, i.e. it’s a limitation of the signal in the first place). This, again, does not describe the sensation of color or lack thereof under low lighting conditions.

Dichromacy is color blindness, again this explains the mechanism but does not describe if a color blind person has the same icons for colors that I do (I’m not color blind).

I don’t know how you keep letting my question go over your head. Perhaps you have never thought of it, never questioned why your perception takes on the form that it does. Nonetheless you have not truly engaged with the question. Every time you read it you convert it to a question about mechanism. It’s not a question about mechanism, I believe the mechanism is described to the same extent you do. I’m asking about sensation. Imagine instead of sight I’m talking about thinking, what forms do your thoughts take? Why do they have the form that they do?

Perhaps the easiest thing to do at this point is have you describe what I’m asking you. There’s no point to further discourse if you provide responses to points I’m not making. If we’re sure we’re on the same page then it’s a productive discussion. And what do you think people mean by the “hard problem of consciousness?”

Daniel

Ben:

“Some modern mathematical Platonists try to claim that the math is the reality, and what we experience is just a shadowy expression of the math. The easiest way to demonstrate the incoherence of such propositions is to invite said Platonists to take a long walk off a short pier.”

Yes, but this form of Platonism actually follows from exactly the same type of argument you use against consciousness,, and exactly the same counter can be used against you. Look:

‘Some modern materialists try to claim that neurons and electrical signals in brain are the reality, and that consciousness is just a shadowy expression of the neurons and electrical signals in the brain. The easiest way to demonstrate the incoherence of such propositions is to invite said materialists to take a long walk off a short pier.”

If you don’t grant reality to ‘consciousness’ as something over and above mere material processes, you simply cannot grant reality to said material processes either, since we can go on and on ‘reducing’ them to ever lower-level entities in exactly the same way you want to reduce consciousness to material processes, until we are left with nothing but pure mathematics….

Look….

neurons can be reduced to molecules

molecules can be reduced to atoms

atoms can be reduced to protons and neurons and electrons

protons and neurons and electrons can be reduced to quantum wave-functions

quantum wave-functions can be reduced to pure mathematical complex numbers

so by your very own reasoning that denies consciousness, the material world can’t be ‘real’ either.

Ben:

“There are those who claim that math exists as its own entity in some ideal Platonic realm, and that we somehow communicate with this realm. You seem like you might fall into this camp.”

My own view is to grant reality all 3 types of properties: Mathematical (basement level), material (next level up), mental (highest level). I agree it doesn’t make sense to say that we can communicate with the Platonic realm though…that part is nonsense. We can only ever know about it via indirect means.

See this interview with top mathematician Roger Penrose talking about ‘What Things Really Exist’ (10 minute watch):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H9Q6SWcTA9w

Interesting counterpoint on NPR.

Sean posted Fear of Knowing

http://www.npr.org/sections/13.7/2016/05/15/478143589/fear-of-knowing

Marcelo Gleiser posted Fear of Not Knowing

http://www.npr.org/sections/13.7/2016/05/18/478488286/fear-of-not-knowing

One can be a substance reductionist and a structure antireductionist. This helps. It is true that everything boils down to quantum fields, but it is also true that structures are greater than the sum of their parts, that complex objects (like brains) have properties that are not inherent in their individual parts (neurons, molecules, atoms, quarks, fields).

So a brain is composed of atoms, but it cannot be explained solely in terms of atoms. It must also be explained in terms of the emergent properties of complex systems composed of atoms.

Jayarava:

“So a brain is composed of atoms, but it cannot be explained solely in terms of atoms. It must also be explained in terms of the emergent properties of complex systems composed of atoms.”

Correct. In fact, at the very bottom, it seems that everything dissolves into pure mathematics, so it seems that the Platonists must be partially right: at the base-level ‘all is number’. So even the ‘material world’ must be an emergent property of pure mathematics.

But Ben rightly pointed out the absurdity of the Platonist idea that everything is just a shadow of pure number. It’s simply not possible to go from ‘pure number’ to ‘material world’ without adding something. So clearly something has gone wrong with the most hard-core version of ‘reductionism’.

The only way out of this paradoxical situation that I can see is that reductionism breaks down, and entirely new emergent properties can appear at higher levels that have an additional existence over and above the lower levels.

That’s why I’m forced to conclude that the mathematical, material and mental worlds all have their own valid type of existence, even though I do lean toward the Platonist idea that mathematics is the most fundamental level.

Daniel, my point in my analogies is that…well, if you’re hung up on insisting being told where the Sun goes at night and won’t accept any answer save one that fits into your model of a land where the Sun travels at night, you’re simply not going to comprehend the actual heliocentric structure of the Solar System.

You’re in the exact same boat with respect to qualia. You’re insisting I explain qualia, when they’re as incoherent and irrelevant to color perception as the Sun’s overnight abode is to celestial mechanics.

I’m guessing you did a bit of Wikipedia research, from which you got your one-paragraph summaries, which is a good start. But did it not once occur to you that, in each description, perception is variable? That the same stimulus produces different responses depending on context? And when reading about dichromats, did it not occur to you that they have different perceptions? Have you not seen the color blindness tests, including the simulations of what they look like to those afflicted? Right there — you look at the simulation, and you have the same perception as the color-blind person does; you have the closest you’re going to get to seeing the world as a color-blind person does.

Here we have a complete understanding of color perception, including ways for you to personally experience everything we’re describing, and that’s still not enough for you.

But how could it possibly be? You still want me to point to the spot on the map where the Sun goes at night, and nothing else will satisfy you.

b&

zarzuelazen:

No. The fundamental problem with Platonism, especially modern mathematical Platonism, is mistraking the map for the territory — and this gets to your other recent posts, addressed to me.

We can most safely take it as a given that the Sun rises in the East, and we need not give serious consideration to any proposals to the contrary. (Yes, yes — supersonic jets at high latitudes, Venus, and so on. Imagine as many footnotes here as will make the pedants happy.) But the reality is the actual motion of the Earth, not our descriptive language of it. And it didn’t have to be the way it is — either the reality or the language.

We know from experiments, especially the LHC, that the math of the Core Model is an even more precise map of reality than the very crude, “Sun rises in East” map. And, just as we can and should laugh off suggestions that the Sun deviates from its East-to-West path across the sky, we should also laugh off suggestions that physics deviates from the Core Model…but, again, both the Core Model and “Sun rises in East” are maps. Very useful and very reliable maps…but still just maps.

Want proof?

I can trivially create other maps that are equals to the ones we use, save they are maps of territories that don’t exist. “Sun rises in West” is a valid map of Venus, but not of Earth. Any competent physicist could take the Core Model, tweak the math to the point that it’s as internally consistent as “Sun rises in West,” and thereby create another map…but a map that we know has no bearing on reality whatsoever. So, clearly, that mathematical map doesn’t exist any more than the Sun rises in the West…but you have no way of knowing that just by looking at the map.

The constant isn’t the mathematical map; it’s the real territory.

So, yeah. I know that cognition is Turing-equivalent computation, just as I know that the Sun rises in the East. It didn’t have to be so, and you could propose all sorts of other maps that function otherwise…but, just as we’ve observed the Sun rising in the East, we’ve observed that reality is described by the computable Core Model, so arguing otherwise — that the Sun actually rises in the West or that cognition isn’t computable — is futile.

Cheers,

b&

Ben,

The brain science at the present time only addresses the mechanical *causes* and/or *correlates* of consciousness, not necessarily consciousness itself. That is to say, even if the brain is definitely computational, it is not a-priori obvious why computation should be identical to conscious experience. So the puzzle of the hard problem remains: how is it that computation could be equivalent to consciousness?

You don’t really address any of the points I or others have raised. As I said earlier, if you start with the axiom that ‘the only valid explanation for anything is reductionistic physics’, it’s no surprise that that’s the only conclusion you can draw. So I think we will end the debate here.

But we do agree on one point: if science can come up a detailed model that can account for the observed behaviour of conscious agents without having to use concepts like ‘qualia’ or other mental qualities of what’s going on, then at that point I will agree that there is nothing left to be explained and that a reductionist physics account is correct.

Cheers

Ben this quote is the heart of the matter:

You won’t even internalize my questions because you dismiss it as incoherent without giving it a thought. You have not explained your grounds for incoherence except for the following points:

1) Perception of color in humans is completely understood

2) It just is incoherent

You have not once addressed this question without begging the question. Don’t assume it’s incoherent, write out your explicit argument for why it’s incoherent. You can’t use 1) the way you’re using it either, which is to assume since the theory is “complete” so anything else can’t exist without contradicting this “completeness.” It’s complete for a certain set of questions, the ones you’ve assumed a priori as being coherent. Now that you can’t make that assumption about the question of qualia, you can’t use 1) in that domain.

Wikipedia was helpful for some but not color adaptation. So I skimmed a few papers here and there about it to make sure they didn’t actually solve the hard problem of consciousness as you claimed. However, I think this part of your response should round up this conversation:

This is your concession right here, “the closest you’re going to get.” Right here you admit the limitations I’ve been asking you about for over a day. I see as the color blind person does through my own icons for color, but by your admission, I cannot see through the icons they would have. You dismiss that ever asking about such a thing is incoherent, but you have sight, you don’t know that your “red” is my “red” despite us having the same perceptual mechanism. You can’t know it through science, so you dismiss it as generally incoherent. But that doesn’t mean the question is incoherent, it means the answer is. The Godel sentence G is not incoherent just because it lacks a proof. It is simply an unknowable feature of the system but it definitely exists in a model of arithmetic, that statement can be expressed coherently and has a truth value in every model of arithmetic. Just like G, qualia has semantic meaning because you’re not a zombie who just reacts, you have an inner life. It is an undeniable feature of the universe. You have to deny your own experiences/sensations to exclude the statement of qualia/hard consciousness from your ontology.

On the sun setting analogy, I accept the same model framework you do, we’re holding the same map and I’m not asking where the sun goes at night. Stop projecting the opposition you want onto mine. You still haven’t told me how you interpret my question, so I can’t even be sure you’re internalizing it as I intend it. Perhaps you want to show your conviction in your worldview, but who cares about being right? That’s not the point. Have a discussion, let down some barriers and assumptions. Explore the “what if” of the other person’s position even if they’re wrong, especially if they’re wrong. That’s the only way you’re going to understand how they got to that position.

Daniel

Again, that’s where I’m coming from, yes — but it’s a conclusion based on analysis of observation, not axiomatic.

https://www.preposterousuniverse.com/blog/2010/09/23/the-laws-underlying-the-physics-of-everyday-life-are-completely-understood/

Especially with the Higgs, we now know as surely as we know that the Sun rises in the East that we would have long since observed anything not in the Core Model, and that any proposals for something significant at human scales not already accounted for irreconcilably contradict overwhelming evidence already gathered.

In other words, if you want to convince me (and, I’m sure, Sean) otherwise, you’re going to have to demonstrate fatal flaws in innumerable experiments over history, including the best and most up-to-date (and ongoing!) experiments we’ve ever performed. Indeed, you’re probably going to have to show that Newton’s Apple didn’t accelerate towards the center of the Earth at about 10 m/s/s. Might as well embark on demonstrating that the Sun rises in the West after all.

As I’ve been trying to show, we already have a detailed model of color perception in which “qualia” is irrelevant and incoherent. Other parts of cognition, such as other senses and motor control, are equally well explained. “higher-level” cognition is coming into focus nicely, and we even have a good working model of self-awareness based on mirror neurons.

Considering that your counter proposals contradict LHC experimental observations plus the naturalistic model nearing completion…what more, really, could you possibly want?

Is it really reasonable to suspect that there might be faeries at the foot of the garden after all, since you still haven’t finished planting the rose bed but everything else is done? And would you really be satisfied even after the roses are in full bloom?

How much more do you really need?

Cheers,

b&

Is everyone aware of the Chinese room?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_room

“The experiment is the centerpiece of Searle’s Chinese room argument which holds that a program cannot give a computer a “mind”, “understanding” or “consciousness”, regardless of how intelligently it may make it behave. “

James,

I like the Chinese Room analogy but I think it still makes one too strong of an assumption. I don’t think that man in the room should even have the knowledge he’s doing a task or following a prescribed set of rules. The man has no self-awareness of the task. I think it’s fair to say this true for all computational devices. It only strengthens the argument but I think it also preempts a lot of of responses.

Daniel

zarzuelazen,

It may be correct for every question it does have an answer for but it won’t necessarily contain answers to every coherently expressible question of the model. In science we’re used to the failure of a theory being that it provides a wrong answer, but sometimes a failure can be that it doesn’t provide any answer even to coherently expressible questions. That failure could possibly be an unavoidable feature if you want said model to be consistent and/or predictive, I think that’s where it’s important that your philosophy be broader than your science.

Daniel

James,

The “Chinese room” presupposes something that’s so incoherent that it’s difficult to even express…namely, that an agent can be self-aware without being aware of the self. That is, the man in the room is simultaneously sufficiently aware of everything he’s describing to be able to describe them, but also not even aware of them at all.

It really comes down to something analogous to imagining a substance just like water, including that it flows at room temperature and coats substances and soaks into fabrics and wicks and all the rest…but it isn’t actually wet. Well, then, what is it you mean by, “wet,” then? How is something supposed to be able to have all the properties of wetness without being wet?

Or a geometric figure that’s the set of all points equidistant from a single point, but that isn’t a circle…or a massive celestial object that’s self-luminous through sustained fusion that isn’t a star…or….

The only way I can even begin to parse the “Chinese room” scenario is if its proponents think that conscious self-awareness isn’t the state of being consciously self-aware…but, again, I’m at an utter loss as to what conscious self-awareness is actually supposed to be, then.

What on Earth are you talking about if somebody who’s consciously aware of the internals of the self isn’t consciously self-aware?

And if you don’t even know enough about what consciousness is to be able to put it into words…what makes you think that whatever you think you’re pointing to is actually real in the first place?

b&

Daniel, we’ve been here before multiple times.

I can completely describe the biological mechanism of color perception; I can model it perfectly; I can predict it precisely; and I can even give you the inner personal experiences of color perception — “induce qualia,” if you like…but that’s still not enough for you.

And why?

Because I’m showing you a schematic of the Solar System and its elliptical orbits, when you’re pointing at your map of the Earth wanting me to identify the cave where the Sun hides at night so you can pluck some of its feathers to put in your headdress.

I mean, my explanations for color perception are even more personally and emotionally persuasive than the textbook explanations for the atomic model. I can show you two radically different colors that we both agree have the same “qualia,” and I can modify them in ways we both agree upon; in stark contrast, you’ve never seen, touched, or tasted an individual atom, let alone its nucleus.

No.

Just as you’d dismiss as nonsense a claim that the Sun rises in the West and that apples fall up, I dismiss your claim that consciousness is something that doesn’t reduce to the Core Model (in the same way that climatology reduces, through weather and gas dynamics and chemistry and atoms and quarks).

Do you understand how utterly fallacious it would be to propose that apples sometimes fall up, perhaps when somebody thinks at them hard enough? If so, you should understand why I consider it equally utterly fallacious to propose that the Core Model is an inadequate underpinning to consciousness.

If you disagree with this point, your knowledge of physics is as lacking as would be somebody who thinks that, maybe by exertion of sheer mindful willpower, he could cause apples to “fall” into the heavens.

Yes, yes. You personally experience color and you think that makes it special. But the cave man personally sees the Sun go down at night, and here you are telling him that the Sun doesn’t move at all, that it’s the Earth that moves, when any fool can tell you that the Earth is the one thing that never moves (except in an earthquake).

Between the two of us, I’m the astronomer who can predict eclipses and retrograde motion and all the rest, and I’m the one telling you that, yes, I know things appear to you the way you’re describing…but those appearances are deceiving and become incoherent once you take into consideration all that we actually know — that, for example, stars would have superluminal velocities were they orbiting the Earth.

But you don’t even realize that light has a velocity in the first place, so why should that fact bother you?

So, again: how do you explain to the cave man that “show me where the Sun goes at night” is incoherent? Where do you start?

Because that’s exactly where I’d need to start with you on color perception.

b&

Ben,

I know this is difficult to understand. It is a “thought” experiment so it requires some thought.

Let quote from the Wikipedia:

The question Searle wants to answer is this: does the machine literally “understand” Chinese? Or is it merely simulating the ability to understand Chinese?[6][c] Searle calls the first position “strong AI” and the latter “weak AI”.[d]

Searle then supposes that he is in a closed room and has a book with an English version of the computer program, along with sufficient paper, pencils, erasers, and filing cabinets. Searle could receive Chinese characters through a slot in the door, process them according to the program’s instructions, and produce Chinese characters as output. If the computer had passed the Turing test this way, it follows, says Searle, that he would do so as well, simply by running the program manually.

Searle asserts that there is no essential difference between the roles of the computer and himself in the experiment. Each simply follows a program, step-by-step, producing a behavior which is then interpreted as demonstrating intelligent conversation. However, Searle would not be able to understand the conversation. (“I don’t speak a word of Chinese,”[9] he points out.) Therefore, he argues, it follows that the computer would not be able to understand the conversation either.

It is a question of whether Searle understands Chinese and the conversation he is having, not whether Searle is elf-aware and can think?

It is an analogy.

But Searle understands English, right? And he reads the resulting English translation, right?

Once you add that unavoidable piece to the puzzle, the incoherence of the “experiment” again becomes apparent.

If Searle is simply mindlessly and uncomprehendingly flipping bits according to the instructions in a rulebook, his own consciousness is a red herring as it doesn’t even enter the picture.

If Searle reads and comprehends the English translation before passing it out of the room…well, again, his own consciousness is irrelevant because he could just as easily read the translation right after it comes out of the room.

In neither case is Searle’s own consciousness even remotely relevant to the matter. It adds nothing whatsoever, never even comes into play…

…so what part of the thought experiment is supposedly related to consciousness?

b&

Ben you still refuse to engage with my question and your analogies always paint me as the primitive and you as the divine teacher coming down. It’s hard to have any serious, respectful discussion with somebody who keeps using such self-serving metaphors. I have my degree in physics too, I’m not some primitive looking up to you for enlightenment. When you wish to engage with the question or at least explicate why it’s incoherent perhaps we can have a real discussion. To flip a condescending metaphor on you, I’m asking you in the absence of a fossil record to explain how mutations, when accumulated over some time, do not result in speciation and your answer is “that’s incoherent because God created all species.” Yes I suppose that is consistent with our data since we have no fossil record in this example. However we know about mutation and this is a possibility we are limited in timescale on testing. It doesn’t add anything predictively though, it’s not like we have a fossil record, so let’s dismiss “macro” evolution as incoherent.

I’ve pointed out time and again that you have set a contrived limit on questions you wish to answer and thus are completely unsurprised when your model is “complete” on that limited set of questions. You have no method for determining which questions are worth taking seriously except evidently by your ability to answer them. If you do have such a method, you have provided no such logical criteria. I don’t really think that’s very scientific and I’m sure I’m not alone with that thought. If you wish to lay down your insecurities of the validity of hard empiricism you definitely would offer a worthwhile discussion.

Really the next best analogy I have for you besides color is language. You and I, assuming equal vocabularies, can distinguish and categorize words by their meaning and probably agree quite a bit how they group together. We have no way of verifying how we actually impart nonverbal internal, thought-based meaning on those terms though. We can only define them in terms of other words to each other. This is the same with color. We perceptively agree since our internal labels are each consistent with the same phenomenon, but we have no way of calibrating our labels to each other’s labels because I can’t see your labels and you can’t see mine. I’m sure you implicitly accept this fact as I bet you’ve heard a child ask, “how do I know your blue is my blue?” You dismiss the child on the grounds he or she has asked an incoherent question, but you do so only because you can’t provide an answer. You know exactly what the child is asking, it is a completely coherent question. We lack the means to experimentally test it, (at least for now, for all we know we could be jacking into each other’s brains directly in the near future) but that’s not grounds for being “incoherent.”

Daniel

This is why I would model the computation in the Chinese room as a selection of an object following the laws of physics and not a voluntary subject with self-awareness. This is what circuits do, we create an energy landscape such that provided with the right driving forces, the circuitry models a logical operation which we then interpret. Anything not related to the logic of the model we dismiss. We don’t care with what current or voltage value there is across a circuit element from the perspective of computation. We select the features of the system we want to model as our computer.

The man in the Chinese room should be modeled as basically an idiot, a zombie, you know what, actually a mouse. Let’s say this mouse really likes cheese and somehow has a taste for multiple cheeses. His preference at a given time depends on the smell of cheese he is currently exposed to. Each card with English has the smell of a given cheese and thus influences him to desire certain cheeses. You’ve setup the room such that each English card has the smell of a cheese on the corresponding Chinese card. The fact of the matter is the mouse inside isn’t translating anything, he doesn’t even know he’s translating or completing a task. He’s just eating cheese. You already did the translation in a sense when you labeled the cards with cheeses. The mouse is just your labor for determining the exact equivalence of a configuration of English words and a configuration of Chinese characters. A computer is just labor, ostensibly anything a computer does you could do with a pencil and paper. So of course your computer isn’t conscious. You wrote the rulebook, the computer didn’t. And you may say machine learning allows computers to write their own rulebooks….but you provided them a rulebook on machine learning too. There’s nothing happening in there.

Daniel

Daniel, I’ve tried, I really have. I’ve given you an explanation of color perception as complete as any in physics and more visceral than most, one that is devoid of “qualia” and in which the very notion of “qualia” is incoherent, but that’s not enough. You yourself have agreed that your “qualia” is itself variable and inconsistent, and yet even that doesn’t shake your faith in “qualia.”

So, as a last-ditch act of desperation, let me turn it back on you. What could I do to convince you that “qualia” really are as incoherent as the idea that the Sun hides in a cave overnight? Is it even possible for you to admit the possibility, or are you as wedded to your qualia as the cave man is to the immovable foundation of his flat Earth?

But how is that any different from any other phenomenon? You have no direct access to internal atomic structure, either, yet, if you really do have a degree in physics, you’ve no problem agreeing that that internal structure is mostly quarks. Why are you insisting on some ill-defined “better” access to the insides of my skull than to the insides of the atoms in my skull?

Tell me how it is you’re satisfied that atoms are composed of quarks, and what a comparable standard of satisfaction would look like for cognition. But if you’ve got radically different standards for the two phenomenon, why should I take your objections seriously?

b&

You’re presupposing your conclusion, assuming that the labor itself can’t be consciousness.

In the case of machine translation, no, of course, there’s no meaningful self-awareness. There’s nothing in that software that is in any significant way analyzing its own actions. Why should there be?

But if you’ve got a computer that analyzes its inputs to create its own models of surrounding agents, and if it also performs a similar recursive analysis of its own state, building a model of itself the same way it models external agents…would you really insist that that program isn’t and couldn’t possibly be self-aware?

Or: of course, a program that doesn’t do anything remotely relating to self-awareness isn’t self-aware. But why shouldn’t a program that is designed to analyze itself be aware of its own analysis? Indeed, how could such a program not be conscious?

b&

Just some last thoughts.

I have found Donald Hoffman’s Visual Intelligence interesting reading.

Although we tend to think of vision as produced by eyes and brain to be somewhat like a camera, in reality it is much more complicated. Seeing involves not only processing of wavelengths of light, it also involves the application of rules. This rules become apparent when we see see various optical illusions. These rules probably came about as evolutionary shortcuts that allowed us to recognize important aspects of our environment more quickly. The import point is that seeing is not a simple passive process but one that involves learning and active creation of what is being seen. And there is no requirement that what we seem to be seeing represents anything “real” in the world.

Hoffman gives an example of people given VR helmets that turns the world upside down. It turns out after a period of disorientation people adapt to it. When they take off the helmets, they have another period of disorientation but adapt back to normal orientation. So it is pretty clear we can adapt and function with radical different visions of the world . What we see only needs to be consistent but it could be right side up or upside down and it wouldn’t make any difference. In the same way, what we seem to see doesn’t need to be anything like what is in the “real” world. So in part the answer to why we see red probably is that it is just arbitrary representation of color that evolution created (maybe to help us recognize ripe fruit) but it could have been represented as green or blue.

The same can be said for hearing, touch, and smell, although with humans sight is the dominant sense.

If you extend this principle to the high reasoning functions, you will realize that these high functions also are also actively shaping the world and that simplification must be important part of it. We are not passively understanding the world but molding it through interaction with it.

Mathematics and science are a part of this process and their goals in most cases is to derive the most simple answer possible to any problem presented. Atoms and waves certainly exist but they exist mostly as simplified representations that our mind makes of the world.

We would like to think that science progresses. We get more facts, create more theories, test them, and get closer to truth, gradually of course, but ever more approximating understanding “reality”.

I am beginning to doubt this to a degree. Progress in science may be more like the change from Windows 7 to Windows 10. Yes, things are different. It looks different. We do things differently. But at the core nothing much is changing under the covers of the operating system. In same way progress is science is not moving us in any fundamental way closer to understanding “reality”. It may seem we are learning new things or disproving old ones but mostly what we are doing is equivalent to swapping one icon on the desktop for a different one.