One of a series of quick posts on the six sections of my book The Big Picture — Cosmos, Understanding, Essence, Complexity, Thinking, Caring.

Chapters in Part Five, Thinking:

- 37. Crawling Into Consciousness

- 38. The Babbling Brain

- 39. What Thinks?

- 40. The Hard Problem

- 41. Zombies and Stories

- 42. Are Photons Conscious?

- 43. What Acts on What?

- 44. Freedom to Choose

Even many people who willingly describe themselves as naturalists — who agree that there is only the natural world, obeying laws of physics — are brought up short by the nature of consciousness, or the mind-body problem. David Chalmers famously distinguished between the “Easy Problems” of consciousness, which include functional and operational questions like “How does seeing an object relate to our mental image of that object?”, and the “Hard Problem.” The Hard Problem is the nature of qualia, the subjective experiences associated with conscious events. “Seeing red” is part of the Easy Problem, “experiencing the redness of red” is part of the Hard Problem. No matter how well we might someday understand the connectivity of neurons or the laws of physics governing the particles and forces of which our brains are made, how can collections of such cells or particles ever be said to have an experience of “what it is like” to feel something?

These questions have been debated to death, and I don’t have anything especially novel to contribute to discussions of how the brain works. What I can do is suggest that (1) the emergence of concepts like “thinking” and “experiencing” and “consciousness” as useful ways of talking about macroscopic collections of matter should be no more surprising than the emergence of concepts like “temperature” and “pressure”; and (2) our understanding of those underlying laws of physics is so incredibly solid and well-established that there should be an enormous presumption against modifying them in some important way just to account for a phenomenon (consciousness) which is admittedly one of the most subtle and complex things we’ve ever encountered in the world.

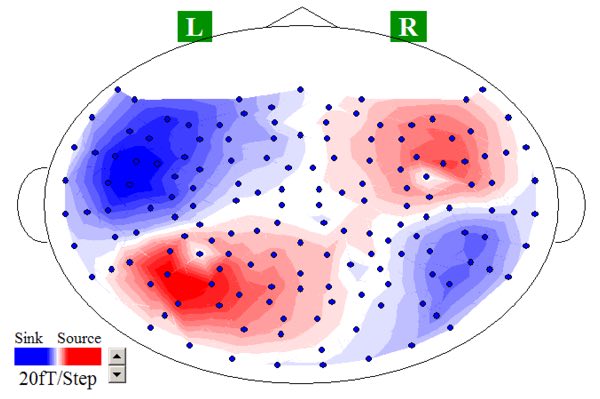

My suspicion is that the Hard Problem won’t be “solved,” it will just gradually fade away as we understand more and more about how the brain actually does work. I love this image of the magnetic fields generated in my brain as neurons squirt out charged particles, evidence of thoughts careening around my gray matter. (Taken by an MEG machine in David Poeppel’s lab at NYU.) It’s not evidence of anything surprising — not even the most devoted mind-body dualist is reluctant to admit that things happen in the brain while you are thinking — but it’s a vivid illustration of how closely our mental processes are associated with the particles and forces of elementary physics.

The divide between those who doubt that physical concepts can account for subjective experience and those who are think it can is difficult to bridge precisely because of the word “subjective” — there are no external, measurable quantities we can point to that might help resolve the issue. In the book I highlight this gap by imagining a dialogue between someone who believes in the existence of distinct mental properties (M) and a poetic naturalist (P) who thinks that such properties are a way of talking about physical reality:

M: I grant you that, when I am feeling some particular sensation, it is inevitably accompanied by some particular thing happening in my brain — a “neural correlate of consciousness.” What I deny is that one of my subjective experiences simply is such an occurrence in my brain. There’s more to it than that. I also have a feeling of what it is like to have that experience.

P: What I’m suggesting is that the statement “I have a feeling…” is simply a way of talking about those signals appearing in your brain. There is one way of talking that speaks a vocabulary of neurons and synapses and so forth, and another way that speaks of people and their experiences. And there is a map between these ways: when the neurons do a certain thing, the person feels a certain way. And that’s all there is.

M: Except that it’s manifestly not all there is! Because if it were, I wouldn’t have any conscious experiences at all. Atoms don’t have experiences. You can give a functional explanation of what’s going on, which will correctly account for how I actually behave, but such an explanation will always leave out the subjective aspect.

P: Why? I’m not “leaving out” the subjective aspect, I’m suggesting that all of this talk of our inner experiences is a very useful way of bundling up the collective behavior of a complex collection of atoms. Individual atoms don’t have experiences, but macroscopic agglomerations of them might very well, without invoking any additional ingredients.

M: No they won’t. No matter how many non-feeling atoms you pile together, they will never start having experiences.

P: Yes they will.

M: No they won’t.

P: Yes they will.

I imagine that close analogues of this conversation have happened countless times, and are likely to continue for a while into the future.

I think this gets right to the heart of the matter.

The only way that your sentence can even make sense in this context is if you are taking the position that consciousness is an actual material substance, and not simply a form of computation.

It should be obvious why consciousness can’t possibly be a material substance, but I suppose I could lay it out for you if absolutely necessary…so, instead, let me give you a trivial demonstration that, at the least, consciousness is significantly computational.

…and, to do that, all I have to do is ask you to recite your multiplication tables or otherwise demonstrate that you have the same sort of competency in mathematics (including geometry and logic) as any adult in our society. Humans are fully capable of doing everything a Turing machine does, though we do tend to have rather restrictive limits on memory and speed when it comes to these sorts of tasks. Nevertheless, the fact that we can consciously do so trivially shows that cognition at least partly encompasses computation.

Once we’re at that point, the only remaining question is whether there’s anything to thought that goes beyond the computable — that is, whether or not Church-Turing holds. And, on that question, I credit Sean with a rather definitive answer. As Sean repeatedly points out, the physics of human-scale phenomena are entirely accounted for — and, as I like to add, that physics is entirely Turing-computable. A claim that there’s something going on in human brains that isn’t Turing-computable is a claim that physics itself is incomplete (at human scales) — but Sean will be delighted to tell you why we should be overwhelmingly confident that’s not the case.

So, yes, really, we honestly do know that cognition is a form of computation, and that it’s something that brains do. We don’t need to appeal to mystery to identify the fundamental nature of consciousness any more than we need to appeal to mystery to explain where the Sun goes at night.

Cheers,

b&

Daniel Kerr:

Eh, no.

The Incompleteness Theorem only applies to infinite systems — and, to a limited extent, systems smaller than the one you’re trying to analyze. Even chickens are capable of solving Tic-Tac-Toe, and it’s trivially obvious that pocket calculators always halt. Once you realize that, you also realize that all computing devices ever actually constructed also halt — due to power interruptions if nothing else.

So, unless you wish to claim that humans are infinite (or trans-finite?) computational devices, the Halting Problem simply doesn’t apply. “All” that’s necessary is a computer that’s sufficiently “bigger” than a brain plus the right algorithm, and Bob’s yer uncle.

We’re, of course, a long way from that kind of computing power — especially if, as may well be the case, we have to brute-force the problem by simulating the brain at the level of the synapse, more especially if we have to go to even finer scales.

But we don’t have to actually build such a device to know that that’s what’s going on any more than we have to walk on the Sun to know that it’s a mass of incandescent gas, a gigantic nuclear furnace.

Cheers,

b&

Daniel Kerr:

In physics, a superlative shortcut to determining if a particular idea is worth pursuing further is to see if you can come up with a way to use the idea to build a perpetual motion machine. If you can, you know the idea is bunk and you don’t need to waste any more time with it. A good alternative is if the best way you can come up with to implement the idea requires a perpetual motion machine (or its equivalent).

Similar concepts work in other disciplines. If your plan for world peace means you’d be crowned philosopher-king for life and be surrounded with a personal harem of your most desired variety, or if the only way to implement it is to become philosopher-king for life, you’re running afoul of a rather fundamental principle of political science.

I would propose that the equivalent for studies of consciousness and cognition would be whether or not your proposal results in or requires consciousness for inanimate objects, such as stones or individual atoms.

It doesn’t matter how you get there; if your grand theory of mind does that sort of thing, it’s as dumb as a sack of rocks. Nice try, but that’s your cue to start over again.

Cheers,

b&

zarzuelaezen:

Very true.

Which is why Newton observed falling apples, Rutherford showered electrons on gold foil, and CERN built the LHC.

We didn’t know in advance what reality consisted of; the best guess a few thousand years ago, Democritus’s atomic theory, wasn’t that far off…but it wasn’t then persuasive enough to stave off Platonic misconceptions that plagued us with nonsense about elemental fire for millennia.

But…now we do know what reality consists of, at least at (and far beyond) the scale of everyday life. As far as you and I are concerned, with rounding, it’s just quarks and electromagnetism mostly behaving the way Newton described, with a nod to chemistry that Lavoisier basically had figured out and Mendeleev pretty much completed. Rarely, you might need to dip just the tip of your toe into Quantum Mechanics (lasers, some biology like photosynthetic efficiency) or Relativity (the navigation app on your smartphone). Unless you’re a theoretical physicist (or like to play one), nothing beyond that is even vaguely relevant to your everyday life — and we’ve got several layers to go until we get to realms where the theoretical physicists are unsure what’s going on.

You might like to point out that even the theoretical physicists don’t have all the answers, and point to things like dark energy or the LHC’s hints at physics beyond the Higgs as evidence. And, on the one hand, you’re absolutely right: there’s some really exciting and fascinating stuff going on in physics these days, and we can reasonably hope to live to see yet another revolution in our understanding of the way the Universe works.

But…that’s entirely irrelevant to everyday life.

Einstein didn’t overturn Newton, and Einstein is entirely irrelevant to biology. Quantum mechanics is almost, but not quite, entirely irrelevant to biology…you could ignore quantum mechanics when doing biology and wind up with the same scale of error as you’d get plotting Mercury’s orbit without Einstein: nowhere near enough to change your navigation plan to send a rocket there.

All of Einstein and all of Quantum Mechanics…they all give the exact same answers when applied to human scales as Newton did — which is a big part of how we know that they’re right. Similarly, whatever comes after Einstein and Quantum Mechanics is going to reduce down to the same answers we have at relativistic and quantum scales, and in turn to Newton as human scales; it must or else we’ll know that it’s not the right answer. And any future revolutions will have to, in turn, similarly resolve downwards.

So, no. I’m not at all presupposing that reality for humans rests upon a fundamental base of quarks and electromagnetism. That’s the conclusion, a most hard-won conclusion that’s come only after millennia of painstaking investigation by countless numbers of brilliant people.

And we really are at the point today where suggesting that there’s something else at play is as absurd as suggesting that maybe the Moon does shine of its own internal light after all because the Sun couldn’t possibly be bright enough for the Moon to be merely reflecting Sunlight.

Cheers,

b&

Ben Goren,

This sounds more like your own personal bias than a logical argument. It’s not inherently unreasonable to expect the that a complete description of the universe should be able to capture its features which are only realized by emulation. Obviously this is impossible in practice by any scientific procedure we might come up with but that doesn’t make it incoherent. You wouldn’t call Laplace’s demon incoherent just because it isn’t possible.

An axiomatic system approximately realized by a finite model doesn’t make the axiomatic system itself finite. Yes none of our computers are truly Turing machines because they have limited resources but they approximate a Turing machine and converge in the limit of infinite computing resources. If you want to argue that computers’ finiteness has to be taken into account, then my point holds even more strongly since a Macintosh and Windows would actually be different finite models of potentially different axiomatic systems. This also means you can’t view them as Turing machines, so you’d have to adjust your own arguments accordingly. This would apply to your analogies of the human brain as well. Statements in the Macintosh system about how the Windows machine executes Windows would not even be decidable for a finite model.

In general I caution you against relying so much on Turing machines as an analogy to understand the physical world. Turing machines are abstract devices for dealing with descriptions, the universe is not a Turing machine, the universe doesn’t “compute” anything. Physics just happens. The description is what’s computed and the universe almost never does that, except when we do it. Turing machines have the same limitation as descriptions. There is no logical argument supporting the reduction of of everything “real” in the universe to what’s Turing computable and the exclusion of anything uncomputable. What’s important is to sort what’s useful for science, not what’s necessarily “real.” A model of consciousness that features non-Turing processes is not useful to us, so it should be dismissed. It doesn’t mean there aren’t features that aren’t Turing computable, it just means those features have no useful model.

And even then, most human scale physics is not actually computable depending on what you want to know. The n-body problem is computable in the sense that given a state you can predict the next state to arbitrary precision determined by your resources. However if you want to know if one body will come into the neighborhood of another at some point on the trajectory, you will not be able to compute that answer. Having a computable list of axioms (i.e. countable axioms or a finite set of axiom schema) is not the same as having a computable theory. Obvious counterexamples include ZFC for one. Your statement that consciousness can’t be Turing uncomputable because the laws of physics themselves are Turing computable doesn’t hold without us having to even considering a possibly uncomputable set of axiom schema. Sure the laws of physics will approximate consciousness to arbitrary precision, but there are inherently uncomputable questions about the system much like with the n body problem. This should be obvious when you realize that physics can express Peano arithmetic and physics has to have at least countably infinite models. Physics does after all take place in a continuum of spacetime. Every finite length trajectory has a countably infinite number of states it explores in classical physics. Our approximations allow us to model most systems discretely and thus with finite models, but for chaotic systems a discrete model might never converge to the corresponding continuum model.

Daniel

Ben Goren,

There is no logically justified argument for you position. You are appealing to absurdity. You have no way of evaluating the claim, that doesn’t make it not true. The question is if it’s a useful explanation for the hard problem of consciousness. It is because there’s no burden for emergence, it’s always there and consciousness is just one class of qualia in the universe. It can’t be measured, but neither can your actual consciousness (or mine), so you don’t have a tool for sorting through these theories. As such, a sensible philosophy is one that accommodates both possibilities, specifically, one that does not assign a prior probability of zero to one of them.

Daniel

You’re still missing the point.

Not only has nothing every been observed that isn’t accounted for by what Sean refers to as the “Core Model,” the observations that we’ve made only make sense if the Core Model holds true at relevant scales. Claims that consciousness isn’t part of the Core Model are no different from claims that the gods must shepherd the planets in their orbits.

As to your complaints about the computability of physics…Randall Munroe put it far better than I could:

https://xkcd.com/505/

Cheers,

b&

In a sense, yes. As Saint Sagan so eloquently put it, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence — and a claim that rocks have thoughts is about as extraordinary as it gets. So, either you’re not proposing thinking rocks but you’re brutally abusing the language, or you are proposing thinking rocks…in which case I’m not even going to pretend to waste my time on such nonsense unless you can come up with some sort of equally-extraordinary evidence.

Simply positing philosophical necessity as a result of your philosophical pondering doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface. If you want me to consider the possibility that rocks can think, you’re going to have to at least show me some rocks reacting to stimuli or something like that. “Good luck with that,” as the saying goes.

I wouldn’t rule it out absolutely a priori, for the simple reason that I wouldn’t rule anything out absolutely a priori. But I take it no more seriously than I would a claim that the Sun might rise in the West tomorrow.

Cheers,

b&

Ben Goren,

Nobody’s saying that consciousness is beyond the core model, but rather the relevant questions are not computable by the core model.

I don’t know what your point is by citing xkcd here. I like that comic but it does nothing to invalidate my point. He is implicitly making the same assumption that you are, “if it doesn’t have a computable representation, it’s not real.” I’m asking you to challenge this assumption, your response is simply to reinforce it without providing any counter to points raised by me or others here. It seems to me you’re conflating “the set of usefully describable objects in the universe” with “the set of real objects that exist in the universe.” There’s no doubt that the most pragmatic position is to act as if there’s no hard consciousness but that doesn’t mean it isn’t a phenomenon. Physics is not everything, not even at human length scales. It’s just everything we could hope to be pragmatically consistent.

Daniel

Nobody’s saying you have to believe the claim. That was never my position. My position since my first comment was that poetic naturalism assigns a zero prior probability to this possibility. It makes it a good philosophy for science but as a result it’s not an inclusive general philosophy. I assumed the inclusiveness was Sean’s intention and I merely point out that it isn’t inclusive in that regard. Rocks being conscious is just one such example. I’m not asking you to seriously consider whether rocks are conscious or not as a paradigm of future science.

Daniel

The first half of that is fair; the second, that I’m not providing a counter, is not.

The counter is nearly trivial.

Were there something more than the Core Model, the LHC would have found an otherwise-accountable particle with a mass less than the Higgs’s ~125 GeV/c^2. But the LHC’s search was comprehensively exhaustive, and no such particle was found.

That’s a simple statement, and one that might at first blush seem nowhere near enough to rule out all other possibilities and come to the conclusions I’m presenting here. However, as Sean himself has so eloquently explained in other venues, that conclusion is the most reliable one a person can reach in the entirety of human history.

In other words, with the discovery of the Higgs, the team at CERN overwhelmingly emphatically demonstrated naturalism as the complete explanation for reality, period, full stop. Any arguments you might have to the contrary were rendered moot by that discovery. We now know without any reasonable room for doubt that naturalism is the answer, the whole answer, and nothing but the answer — no matter the question.

Sean’s point, I think, in using the “poetic” adjective, is that this is cause for celebration and joy and wonder and delight, not for despair. Nature itself is the greatest epic poem imaginable! But it’s also the only game in town, whether or not you believe or wish it to be so.

You can protest all you like that we should remain open to the possibility that nature should be this or must be that or can’t possibly be this other…but there’s no more point to such protestations than a similar insistence that you can walk off a cliff without falling.

You might not understand the answer; you might not accept the answer; you might not like the answer. But the Higgs really does have a mass of ~125 GeV/c^2 regardless.

Cheers,

b&

I think what would save me from another paragraphs long response that perhaps is not as well calibrated to your point as I would think a priori would be just to ask you this question: Do you believe that science is or can be a complete description of the universe? I mean complete in the sense that every element of the universe can be committed to consistent, computable, description?

I ask this because your response regarding the Higgs does not address my point at all. I’m asking if there is phenomenon a perfect theory of physics cannot capture. A secondary question is do you believe the core theory contains the answer to the hard problem of consciousness?

I think if I know your explicit position on these questions I can have a more concise and effective response.

Daniel

Daniel,

Science broadly construed is the only method humanity has ever come up with that has any proven reliability at coming up with answers that justify confidence. By, “science broadly construed,” I mean the apportioning of belief in proportion with that indicated by a rational analysis of objective observation. Your conclusions must follow directly from actual observed phenomenon, and you shouldn’t be any more confident in them than your error bars indicate.

As to whether or not we will have a complete description of the Universe…well, of course, we already know we won’t; the expansion of space means that there are parts of the Universe that were within my event horizon when I started typing that are now outside my event horizon, without even the theoretical possibility that I’ll know what’s going on there. Other examples of horizons of all sorts are trivial to come up with…including the fact that I’m never going to personally experience whatever it is that you’re feeling as you read these words.

But if we adapt a somewhat more useful definition for, “complete,” then we’re already there, with the Core Theory; see my previous posts and Sean as to why this is the case.

To the second part of your question…the Core Theory is complete, and we know this with as much certainty as we know anything. But it’s not necessarily useful for describing phenomena other than at scales very close to the boundaries.

Climate is an excellent example. We use different tools to describe climate from those we use to describe weather, which, in turn are different from those we use to describe the air immediately around us, the chemical composition of that air, the atomic composition of the chemicals, the quarks that comprise the atoms, and so on.

…but we also know that everything the atoms do can be explained by their quarks (etc.), and the molecules by the atoms, and the gas by the molecules, and so on.

The same is true with consciousness. Because we know that the Core Theory is at the foundation, we know that consciousness is a property of the functioning of brains, and we already know that brains are biochemical computation machines, and we already have a pretty good idea of how neurons function, and everything past that goes back to chemistry and atomic theory and eventually the Core Theory.

If you want to put your “something more” for a theory of consciousness at a similar place in the hierarchy of science as climatology, I’m right there with you. And in this particular case, that means that cognition is a particular form of computation.

But the moment you suggest that it’s not something that ultimately rests on the Core Theory, or that it does things not consistent with the Core Theory, that’s where we part ways.

Cheers,

b&

This scenario happened to me last year: I was visiting San Luis Obispo, CA where I went to college and where my good friend Dave now owns his parent’s house there, though he rents it out. I talk to Dave perhaps once a year and I visit SLO every three years on average let’s say. Being a botanist I drove to a hill near his house to investigate a Dudleya species…as I was driving by his house Dave calls me on the cell phone! So, first I think that Dave is in town and saw me driving by but he tells me no–he’s 100 miles away in the Tehachapi Mountains. This to me is an extraordinary coincidence and if it happened once or twice in my life I would put it up to random peaks. But this kind of thing has happened scores of times, so the odds become extra-universal (if that’s a real term, lol). This leads me to think we have connections between ourselves, especially our close friends and family, that link us together and transmit information. Perhaps Jung’s collective unconscious. If so, then the mind may indeed extend beyond the body somehow and needs to be accounted for when building a truly AI human.

I agree with your description of science and what science should aim to do. I think where I differ is that I don’t think it can be a complete description of any system. I believe it’s just the most complete, useful description of any system, where useful is in the sense of your first paragraph.

I should have clarified that by complete I didn’t mean in terms of having a well characterized initial value problem or something like that. I mean complete in the sense that every observation that could be made/experienced in any given subset of the universe could be completely characterized. So for example, describing why red is perceived as red and perhaps why my internal icon for red is not your internal icon for blue (or why it is if our perceptions are not consistent between us).

I’m not saying consciousness as a physical phenomenon is not entailed by the Core Theory, on the contrary, it has to be. I’m claiming that any description predicting its experience/sensation is not contained in the Core Theory. Only the mechanism is contained, not the properties of its experience. You can predict mechanically how an experience would activate neural circuits in your brain and I suppose emulate it that way, but then you’re actually giving yourself the experience if you do this to your brain, that’s no longer a description. My question is do you think the description of this experience is contained in the Core Theory? Could a brain understand how another perceives redness without duplicating the perception in their own brain? If naturalism is true then this has to be contained in the Core Theory. Although I think you’d agree that it’s not. Perhaps these experiences have no scientific description, so be it, it doesn’t mean they’re not elements of our ontology.

Daniel

Daniel Kerr:

I do believe I’ve already addressed the unreasonableness of this demand.

You don’t complain that we don’t have a complete description of Relativity because you don’t have a personal experience of Lorentzian contraction. You don’t complain that we don’t understand Evolution because you haven’t personally observed every single generation (or even a fair sampling) of organisms from your parents back to the last universal common ancestor. You don’t complain that we don’t understand Atomic Theory because you’ve never seen an individual atom with your unaided eye.

Yet exactly that is what you’re demanding with respect to consciousness — that you yourself must “duplicate the perception” of another in your own brain in order to understand said perception.

Once you step back from such unreasonableness…once you have done so, you’ll discover that an Excel spreadsheet I previously linked to is as complete a description of human color perception as E(k) = 1/2 m * v^2 is a complete description of kinetic energy. If you’re satisfied that we completely understand kinetic energy — which we most emphatically do — then you should also be satisfied that we completely understand color perception.

…which, again, is not a claim that there’s nothing more to be learned about color perception. Mapping the chromaticities of a camera’s primaries to the human observer is typically mathematically impossible, and achieving a least-worst match is no small feat, something I personally happen to know more about than 99.99999%+ of humans…and, yet, there’s a small handful of people who’re far beyond me in the field….

(A rough translation: there are colors we can see that cameras can’t and vice-versa, and figuring out how to make the best of that impossible situation such that a picture looks as close to the original as possible is very difficult.)

Cheers,

b&

Of course it’s unreasonable, but that doesn’t mean you dismiss it from reality. To translate what you’ve said in reasonable language, we understand the perception of color within reason. We don’t and can’t understand the hard problem of color perception. Our science can’t do it.

I honestly don’t get your evolution and Lorentz transformation allusions. The whole point of isotropy of spacetime is that I have no way of knowing what frame of reference I’m in. When I look up into the night sky I see Lorentz contraction right in front of me. Perceptually I can’t distinguish between non-Lorentz contracted objects and ones that are, I just see them as moving with different velocities if I make a careful measurement. I can only infer their actual size after this measurement. An explanation of this phenomenon is not at all analogous to Lorentz contraction. A perception of Lorentz contraction in action is irrelevant as its contingent on how I perceive size in the first place. The relevant question would be why I perceive relative size the way I do. This is the aspect that’s analogous with why my icon for redness is what it is. What I perceive as red could have easily been given my icon for blue but it wasn’t.

Ultimately you’re confusing my desire for explanation of my perceptual icons with a desire to directly observe phenomenon. They’re not the same thing. My position isn’t that “you have to experience something yourself to truly understand it,” my position is that what constitutes me experiencing something is not explained by the Core Theory. The fact of the matter is that you or anybody who knows more about color perception can tell me why my icon for redness and my icon for blueness are not switched but are assigned the way they are. You cannot explain what forms these icons take in my mind. You don’t have that knowledge and I argue you never will. You say it’s unreasonable to expect such knowledge, maybe, but I know I have these icons and you know you have yours, so clearly you don’t and can’t have a complete description as there exist obvious questions you can’t answer. Them being unreasonable to answer does not make them unreasonable questions. Clearly you feel the sensation of seeing redness. If you don’t that would clear quite a few things up.

Daniel

Daniel:

There’s a reason why “irrational” and “unreasonable” are pejorative terms, and why most of us dismiss the irrational and unreasonable with prejudice. Persistence in hewing to the illogical has never granted success, so why pretend it might start now?

The principal and only significant exception, of course, is evidence; if you have evidence that contradicts your understanding, you should be confident that it’s your understanding at fault. And, of course, I don’t mean statistical noise or experimental error or the like; I mean actual evidence, such as Michelson’s and Morley’s failure to observe the Aether.

Even were I to grant you the coherence of your complaint, it would still be irrelevant. The Theory of Evolution can’t tell you why your eyes themselves are brown and not blue (or vice-versa), yet that doesn’t represent a failure of the theory to account for the origin of eyes with colorful irises.

I have given you reasonable explanations for all your questions, and, in reply, you have rejected even the possibility that reason might provide you with answers. You are quite determined in insisting that nobody could possibly understand color perception on entirely unreasonable grounds, when, in fact, color is most thoroughly understood. And you use your own lack of understanding as some sort of evidence or proof that nothing whatsoever about cognition can possibly be understood, even though a great deal of cognition is understood at least as well as vision.

All I can conclude from this is that you’re not interested in reasoned discourse, but instead wish to wallow in self-imposed ignorance.

If that’s really what floats your boat, great…but, might I suggest? When you come to something you don’t understand, it’s a lot more fun to try to understand it than to try to tell other people not to bother even trying. Especially when those other people already have it figured out, and are trying to help you get up to speed….

Cheers,

b&

Resulting to a personal attack on my character does not do much for your argument when what you have is an appeal to intuitive absurdity. You can’t explain why my icon for red is “redness.” You know this, and yet you claim you know the answer, yet you are unable to conjure an explanation. If you do have such an explanation, then provide it. That’s how you would know you’re right. Until then it’s up in the air.

And about your evolution point with eye color. It could easily tell you why blue over brown or what have you with a well characterized IVP. We don’t have that data, so we don’t know why one mutation proliferated in a given lineage over another. If you had that data, you could, that’s not a failure of evolution, it’s a failure of data collection. Again, this is not an analogy to the kind of theoretical limitation I’m describing. You seemingly deny your own sensations and I don’t get why you refuse to talk about them. They’re the one thing you know that’s real for you, everything else, including the consciousness of others, is inferred with extra-sensing assumptions. Do you understand what I mean when I say “redness?” Do you understand I’m not referring to the color or the mechanism behind my perception of the color but rather the presentation of redness that mechanism lends me? These are not meant to be condescending questions, I am merely trying to understand how you’re interpreting my views. Right now I’m not confident you could accurately explain my position right back at me. This makes it hard to have a rational discourse when you continue to project the opposition you think you’re receiving on the actual one you’re receiving.

At the end of the day you can’t explain why red is redness and blue is blueness or why it even has a form at all. This is no failure of science, I never claimed that your insistence that is my claim. All I claimed is this was a question outside science’s purview. If you think anything outside science’s purview is a failure of science then I suppose you feel science as a whole is a failure as it could never validate theism vs. atheism or any other competing theory. That’s not my view of science and I’m comfortable with that.

Daniel

It is unreasonable — though, I’ll grant, pervertedly consistent — for you to take umbrage at me for agreeing with you that your own characterization of your demands is unreasonable. But I would further suggest that if it makes you uncomfortable to be reminded that you yourself have identified that you’re being unreasonable, you might want to take that as a sign that, perhaps, being unreasonable isn’t such a good idea after all.

I have, repeatedly, but, granted, not in introductory-level detail.

A very quick crash course. If this isn’t enough, please take it as encouragement for you to either get up to speed on your own or good cause to take it on faith that color is as well understood as any other phenomenon.

Every photon has a wavelength, with no meaningful limits for this discussion on what those wavelengths can be. Photons with wavelengths between roughly 350 nm and 800 nm trigger electrochemical reactions in the retina. Outside of certain rare phenomenon (including lasers), all light that reaches your eyes in everyday perception is a mixture of wavelengths over that range. Light outside those ranges, of course, still reaches your eyes, but you don’t perceive it at all.

Photoreceptive cells in your retina come in three significant categories, classified as “L,” “M,” and “S,” for “long,’ “medium,” and, “short” wavelengths. Cells of each type are sensitive to photons over the entire visible range, but are statistically more sensitive to different parts of the spectrum. Long-wavelength red photons will still trigger a response in the blue-sensitive S photoreceptors, but only a very minimal response comparatively.

The spreadsheet I linked to is, essentially, a plot of the relative spectral sensitivities. (There’re some footnotes I’d insert here were this a textbook.)

If you measure the per-frequency spectral intensities of incident light (at 5 nm spectral resolution for the spreadsheet I linked to, which is plenty good enough for this type of work) and do a bit of math with the data in that spreadsheet, you get coordinates in the XYZ three-dimensional color space. There are formulas to convert those coordinates to any other color space you might like, including RGB color spaces that you’re more likely familiar with. (Many more footnotes to insert here.)

Because there’re only three spectral channels in human vision to represent spectra that can be potentially infinite in complexity, there’re all sorts of cases where two entirely different spectra can cause the exact same perception of color. As such, we get to the point where I can propose a test of the theory…I could set up a scene with an LED bulb, a computer monitor, and an inkjet print (with a certain specified light source shining on it). All three would have significantly different spectra, and yet you’d agree with almost everybody that the three colors are the same.

In other words, I could present to you radically different physical phenomenon that you would experience the same. And I could alter the physical phenomena and predict ahead of time what you would experience. I could even take your report of your experience and make a really good guess as to what physical phenomenon caused it.

If that doesn’t count as a complete explanation of your color perception…then you are, indeed, unreasonable. And I would again urge you to abandon your irrationality and embrace reality.

Cheers,

b&

Ben:

“But…now we do know what reality consists of, at least at (and far beyond) the scale of everyday life. As far as you and I are concerned, with rounding, it’s just quarks and electromagnetism mostly behaving the way Newton described, with a nod to chemistry that Lavoisier basically had figured out and Mendeleev pretty much completed.”

You are definitely presupposing reality there! 😉 I can you give a clear example of something that exists but that cannot be detected by the LHC, or any physical experiment for that matter. Here it is:

The mathematical truth “4*6=24”

I would regard the above truth as something that objectivity exists independently of all human minds. The argument for this is that everyone gets the same answer, and that the property “4*6=24” is indispensable for our explanations of reality.

As I pointed, the criterion for ‘existence’ should not be limited to ‘we can observe it and its physical’, but rather it’s usefulness to our explanations of reality. And I’ve just you an example something entirely non-physical (a mathematical truth) that clearly ‘exists’ by this criterion.

zarazuelazen:

Seriously?

That’s about as trivial to demonstrate as it gets.

Go grab yourself a couple dozen pennies or marbles or whatever you like.

Line them up in a 4×6 grid, and count ’em up.

Other ways of demonstrating the same fact are legion, from ancient Greek geometry to modern IC design.

If you’re instead proposing that some unreal Platonic idealization of arithmetic is somehow actually real, I would refer you to the fact that Aristotelian Metaphysics in general and Platonic Idealism in particular are cringeworthy primitive superstitions and have no more place in modern thinking than the demonic possession theory of disease or the celestial harmonic theory of planetary motion.

Cheers,

b&

Ben Goren,

Fair enough about unreasonability, I did not mean to attack you. The difference in how we use the term is you see it as grounds for dismissal of the existence of a subject if it’s labeled as unreasonable while I only see it as grounds for dismissal of the usefulness of that subject. It’s not the same thing for us and really not perverted, though I will grant you consistent. There are degrees of unreasonable, I’m using it only to the degree of impractical. You are bundling impractical with incoherent, and they aren’t the same.

I actually don’t know the details of the pathway to that detail and thanks for going in depth. Not to put it down because it is amazing to me that we know that much, however, it doesn’t answer my question and I hope you understand why it doesn’t answer my question. Your answer is to the question, “why do I perceive red as a distinct color?” not “why is redness red as I perceive it?” I’m asking about the form it takes, the sensation it produces. Your explanation does not contain that. This is not an unreasonable question because its premise is reasonable, which is I have a sensation of redness when I see the color red and that redness has a particular form that’s distinct from other sensations of different colors ( you’ve answered why they’re distinct but again that’s not the question). So how, mechanistically, is red displayed as redness in my brain? What determines the form of my icon for redness?

Daniel

That isn’t quite true. Really the mathematical truth “4*6=24” together with the set of Peano’s axioms describe a class of objects (models) in our universe that instantiate that claim along with the rest of Peano’s axioms. While the class itself does not exist, members of that class definitely exist.

Daniel

6*4=24

Ben:

“Go grab yourself a couple dozen pennies or marbles or whatever you like.

Line them up in a 4×6 grid, and count ’em up.”

That is empirical evidence yes, but no amount of shuffling physical objects is the same as the mathematical truth that “6*4=24”. This is clear from the fact that the mathematical truth itself is deductive (applies universally), where as the empirical operation you describe is *inductive* (uncertain, based on extrapolation from a specific examples). Arrangements of pennies and marbles are clearly not the same thing as mathematical properties 😉

If that’s not clear to you, you only need to consider examples of other more sophisticated mathematical truths that are clearly true and yet no physical operations can demonstrate them (let alone be reduced to them!) – just look at any mathematical statement that involves infinity.

Ben:

“If you’re instead proposing that some unreal Platonic idealization of arithmetic is somehow actually real, I would refer you to the fact that Aristotelian Metaphysics in general and Platonic Idealism in particular are cringeworthy primitive superstitions and have no more place in modern thinking than the demonic possession theory of disease or the celestial harmonic theory of planetary motion.”

Given that top physicist and cosmologist Max Tegmark just recently wrote an entire book defending Platonism (“Our Mathematical Universe”), I would say that Platonism is still alive and well in the modern world 😉