One of a series of quick posts on the six sections of my book The Big Picture — Cosmos, Understanding, Essence, Complexity, Thinking, Caring.

Chapters in Part Five, Thinking:

- 37. Crawling Into Consciousness

- 38. The Babbling Brain

- 39. What Thinks?

- 40. The Hard Problem

- 41. Zombies and Stories

- 42. Are Photons Conscious?

- 43. What Acts on What?

- 44. Freedom to Choose

Even many people who willingly describe themselves as naturalists — who agree that there is only the natural world, obeying laws of physics — are brought up short by the nature of consciousness, or the mind-body problem. David Chalmers famously distinguished between the “Easy Problems” of consciousness, which include functional and operational questions like “How does seeing an object relate to our mental image of that object?”, and the “Hard Problem.” The Hard Problem is the nature of qualia, the subjective experiences associated with conscious events. “Seeing red” is part of the Easy Problem, “experiencing the redness of red” is part of the Hard Problem. No matter how well we might someday understand the connectivity of neurons or the laws of physics governing the particles and forces of which our brains are made, how can collections of such cells or particles ever be said to have an experience of “what it is like” to feel something?

These questions have been debated to death, and I don’t have anything especially novel to contribute to discussions of how the brain works. What I can do is suggest that (1) the emergence of concepts like “thinking” and “experiencing” and “consciousness” as useful ways of talking about macroscopic collections of matter should be no more surprising than the emergence of concepts like “temperature” and “pressure”; and (2) our understanding of those underlying laws of physics is so incredibly solid and well-established that there should be an enormous presumption against modifying them in some important way just to account for a phenomenon (consciousness) which is admittedly one of the most subtle and complex things we’ve ever encountered in the world.

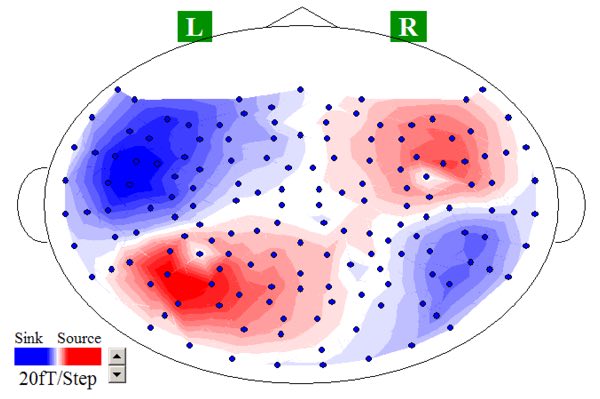

My suspicion is that the Hard Problem won’t be “solved,” it will just gradually fade away as we understand more and more about how the brain actually does work. I love this image of the magnetic fields generated in my brain as neurons squirt out charged particles, evidence of thoughts careening around my gray matter. (Taken by an MEG machine in David Poeppel’s lab at NYU.) It’s not evidence of anything surprising — not even the most devoted mind-body dualist is reluctant to admit that things happen in the brain while you are thinking — but it’s a vivid illustration of how closely our mental processes are associated with the particles and forces of elementary physics.

The divide between those who doubt that physical concepts can account for subjective experience and those who are think it can is difficult to bridge precisely because of the word “subjective” — there are no external, measurable quantities we can point to that might help resolve the issue. In the book I highlight this gap by imagining a dialogue between someone who believes in the existence of distinct mental properties (M) and a poetic naturalist (P) who thinks that such properties are a way of talking about physical reality:

M: I grant you that, when I am feeling some particular sensation, it is inevitably accompanied by some particular thing happening in my brain — a “neural correlate of consciousness.” What I deny is that one of my subjective experiences simply is such an occurrence in my brain. There’s more to it than that. I also have a feeling of what it is like to have that experience.

P: What I’m suggesting is that the statement “I have a feeling…” is simply a way of talking about those signals appearing in your brain. There is one way of talking that speaks a vocabulary of neurons and synapses and so forth, and another way that speaks of people and their experiences. And there is a map between these ways: when the neurons do a certain thing, the person feels a certain way. And that’s all there is.

M: Except that it’s manifestly not all there is! Because if it were, I wouldn’t have any conscious experiences at all. Atoms don’t have experiences. You can give a functional explanation of what’s going on, which will correctly account for how I actually behave, but such an explanation will always leave out the subjective aspect.

P: Why? I’m not “leaving out” the subjective aspect, I’m suggesting that all of this talk of our inner experiences is a very useful way of bundling up the collective behavior of a complex collection of atoms. Individual atoms don’t have experiences, but macroscopic agglomerations of them might very well, without invoking any additional ingredients.

M: No they won’t. No matter how many non-feeling atoms you pile together, they will never start having experiences.

P: Yes they will.

M: No they won’t.

P: Yes they will.

I imagine that close analogues of this conversation have happened countless times, and are likely to continue for a while into the future.

Ben: No doubt progress is made but the fMRI analysis would be akin to taking an infrared photo of a circuit board. The info can be misleading because blood flow tells a lot but is still a secondary effect. In engineering we understand what is actually inside those components and how the manipulated forces of nature are manipulated. Electronics is comparatively crude and we can simulate the computational brain processes or even fake their effects with AI but the naivety of AI researchers who think an electronic circuit can have a subjective experience underscores how little they understand about neurons.

Ben: No doubt progress is made but the fMRI analysis would be akin to taking an infrared photo of a circuit board. The info can be misleading because blood flow tells a lot but is still a secondary effect. In engineering we understand what is actually inside those components and how the forces of nature are manipulated. Electronics is comparatively crude and we can simulate the computational brain processes or even fake their effects with AI but the naivety of AI researchers who think an electronic circuit can have a subjective experience underscores how little they understand about neurons.

Vick, you were doing great until the end. But to leap from “We’re making progress but have a long way to go,” to, “therefore, the explanation is an ill-defined mystical something-or-other that directly contradicts our best and most fundamental understanding of reality” is…well, simply unsupportable.

You might as well cite the current technological limits of imaging the Earth’s core as proof of souls burning eternally in the pits of Hell.

Cheers,

b&

Ben,

In the case of billiard balls, you can clearly use your knowledge of the physical world to explain what’s going on. And your concepts of the physical world can be replaced with an entirely reductionist physics model, namely Newtonian physics.

Whereas, the concepts you use to understand people (conscious agents) have a quite different character, and as yet, there exists no physics (reductionist) model that can explain consciousness. So, as yet, you can’t replace the concepts you use to talk about the mental world with a physics model.

Let’s look the concepts we use to talk the physical world, and compare them to the concepts we use to talk about the mental world. Lets break these concepts down to their absolute essentials , what the basic building blocks of the physical world as compared to the mental world?

Physics:

I think Sean Carroll’s catch-phrase ‘atoms and the void’ is pretty good! Physics , at the absolute base, is really just about matter and space – or, to be more precise, some basic fixed elements (such as particles), transformations of these elements (forces that act on them), and geometrical properties (a background of space and time).

So to summarize, physics is 3 basic things, fixed elements (or ‘symmetries’), transformations and geometry or (in simplified plain English matter, forces and space

Now lets look at the mental world (mind):

Break it down its absolute essentials. Again, there are 3 basic elements: agents, values, and qualia (subjective experience itself). You have goal-directed beings (agents) , that are motived by (values) and have conscious experience itself (qualia).

I think you can see this set of concepts appears to have a totally different character to the physics set!

To reduce the mental to the physical, you need to prove the following:

{Agents, Values, Qualia} (is identical to) {Matter, Forces, Space}

You can see that billiard balls are easily explained by the ‘physical set’ of concepts (matter, forces, space) , whereas minds are falling under the ‘mental set’ (agents, values and qualia), which on the face of it do appear to have a strikingly different character.

Now science tells us that mental things do appear to depend on physical things; that is to say, the physical things are definitely more fundamental than mental things, So our explanation of mental things will indeed have to involve physical things. There’s no question that the mind depends on the brain, and that there *is* a physical component to the mind.

But there’s a strong remaining question-mark over reductionism, the idea that the mind is *entirely* physical, and that we can completely reduce the mental world to physics, without any additional elements being needed in our explanation.

zarzuelazen:

I do not think that Sean would agree with this characterization, especially considering you didn’t even once use the word, “field.”

Your “elements” here have no more bearing on reality than your physical “elements.” Again, glaringly missing from your discussion is both communication and computation, either of which is far more fundamental than anything as nebulous as “agents” or “values” — let alone the ill-defined notion of “qualia.”

I no more need to take seriously such a challenge than I would need to answer a challenge from an astrologer over the classification of Neptune as a planet because there isn’t a corresponding Platonic solid for it.

Then you are equivalently claiming that there exists a particle with a mass less than that of the Higgs Boson that the LHC failed to discover. But we know with more than six sigma certainty that that is not the case, so I’m perfectly safe in dismissing your assertion outright without further consideration — just as you’d similarly dismiss an assertion that maybe the Sun doesn’t rise in the East after all.

Cheers,

b&

Ben,

I was discussing the concepts we use to *talk* about reality, not reality itself.

I’m simply pointing out that the concepts we use to talk about the mind appear to have a strikingly different character than the ones we use to talk the physical world.

As I stated, at the present time, there exists no way to replace concepts we use to talk about the mental world with a low-level physics model, because consciousness still remains unexplained.

The postulation of a failure of reductionism is nothing at all like suggesting something that has been definitely empirically refuted.

A failure of reductionism would mean (empirically) that there would be complex arrangement of matter at a high-level where new laws appear that can’t be explained in terms of lower-level laws. Since consciousness has not been explained empirically, my hypothesis certainly hasn’t been empirically refuted.

All I’m asking for is a reductionist model that explains consciousness in the sense that I can replace the concepts I use to talk about the mind with the new terms in the reductionist model.

Neither you, Sean Carroll (or anyone for that matter) can supply this model. And that’s an empirical fact 😉

zarzuelazen:

That’s hardly surprising. The concepts we use to talk about Newtonian-scale physics appear to have a strikingly different character from the ones we use to talk about Quantum-scale physics, from chemistry, from biology, from cosmology, from geology, and on and on and on.

I started this entire blog post discussion with exactly that. We already have awareness of others in the form of mirror neurons. Point mirror neurons at themselves and you get self-awareness, which is the “hard” part everybody keeps tripping over — and, once you’re past that hurdle, the rest falls out quite naturally.

Cheers,

b&

Ben:

“The concepts we use to talk about Newtonian-scale physics appear to have a strikingly different character from the ones we use to talk about Quantum-scale physics, from chemistry, from biology, from cosmology, from geology, and on and on and on.”

Very true, yes! The trouble is that the vocab gap between mental and physical concepts is greater than the vocab gap between any of the fields you name above. Remember the exercise I suggested in my earlier post of ‘breaking down’ the concepts we use to describe things to their absolute basic ‘elements’ of definition.

All of the fields you mention above, are in some sense, still describable by the same basic ‘elemental’ definitions of ‘physical’ concepts: Symmetries/Matter, Transforms/Force, Fields/Geometry.

(You can debate exactly what basic ‘elements’ of language should be used for describing physical concepts, I took your suggestion of including ‘Fields’ for instance, but it doesn’t change the fact that there’s still a gap between physical and mental vocab).

Ben:

“We already have awareness of others in the form of mirror neurons. Point mirror neurons at themselves and you get self-awareness, which is the “hard” part everybody keeps tripping over — and, once you’re past that hurdle, the rest falls out quite naturally.”

Yes, that’s the sort of model that might convince me. I do take materialism very seriously, I’m just not fully persuaded until I see a clear model that the scientific community generally agrees explains consciousness in the sense it can model all observed agent behaviour in purely physical terms. But certainly if such a model was developed, I’d be finally convinced.

There is another problem with materialism that I want to mention here. Here’s the problem: If we take seriously the claim that consciousness is just a useful ‘language’ that we are using to describe physical signals in the brain, and we willing to ‘reduce’ consciousness to a physical description, then there is no reason to stop at the physical world!

For how do you know that the ‘physical’ world is really the base level of reality? The materialist can’t assume that the physical world is the basic reality, by their very own arguments! For the anti-materialist can simply claim that there is another lower-level of description beneath the physical world that’s even more fundamental, and what you think of as the physical world is really just a ‘useful language’ you are using to describe some higher-level emergent properties of an even deeper reality!

In fact, the position known as ‘Mathematical Platonism’ takes exactly the view I describe above! Platonists believe that ‘mathematics’ is really the basement level of reality, and that what we think of as the physical world is really just a ‘useful language’ to describe certain high-level properties of the true base-reality…numbers! (Read ‘The Mathematical Universe’ by Max Tegmark for arguments along these lines)

Can you see the slippery slope here? If you don’t regard consciousness as fundamental, by the very same arguments, you can’t regard the physical world as fundamental either!

I never got why scientific types would claim that smaller animals do not have a big enough brain to be self-aware or have consciousness. Then they say that we only use a part of our brain that is as big as a point of a pencil at any given time, but then a brain scan like the one shown here would seem to prove otherwise.

I think my gold fish show signs of self awareness and consciousness. I never remember when to feed them, so I have taught them how to “beg”. When they would get hungry, they would start to “swarm” in a up and down motion all together. Then I would only feed them when they did this, and now they “beg” or “swarm” every time they get hungry whenever I come near. Then I can tell if I fed them or not, and I will know when to feed them if I forget if I had or not. Made me think that my gold fish could be smarter then the last dog I owned…

Anyways, I think consciousness could have a lot more to do with impedance. If it is not the atoms themselves that give rise to consciousness, then it would have to do with something about the interaction between them. Then the impedance of brain cells could control that interaction. Our consciousness could just be riding on an electric current. Then that would prevent artificial intelligence from ever becoming self aware or consciousness in the same way we are, because all of electronics was specially designed to have a very low impedance.

A mansion could never become self aware no matter how much you rewired all the light switches in it. Then microchips and all of modern electronics is just based on transistors which just act like switches themselves. It would be like saying a completely wooden mechanical dog could become self aware.

John B.

Agree about smaller animals. Especially birds. Take a look at my “Of Minds and Crows”.

https://broadspeculations.com/2016/04/09/of-minds-and-crows/

vicp

“… the naivety of AI researchers who think an electronic circuit can have a subjective experience underscores how little they understand about neurons.”

Nobody would expect a simulation of a glass of water to be wet or that we could somehow recreate actual water with a circuit board with the right algorithm. Yet people somehow want to argue that consciousness can be simulated or recreated on a circuit board with an algorithm. Ironically, if consciousness could be recreated on a circuit board, then we would prove that consciousness actually is not material since it could be transferred from one material medium to another, that is it would exist independently from its medium.

I feel that poetic naturalism is denying the existence of distinct mental properties and instead sweeping them under the rug of “how we express” these complex neuronal structures in ourselves. Clearly consciousness is a real phenomenon, it’s not just window dressing for the physics underlying the phenomenon. I think it’s the other way around, physics is the window dressing for the phenomenon.

The poetic naturalist here is assuming the science is fundamental and the experience is secondary. “Everything is made of particles interacting with each other through fundamental forces.” As physicists we believe everything starts from the ground up and the ground is physics. But physics is merely our description of the ground, it is not itself the ground. Science is reductionist, you shouldn’t expect it to accurately reflect aspects of reality which cannot be measured, such as internal experiences. Physics implies atoms have no experiences, but it actually doesn’t make a statement one way or the other because as a theory it doesn’t have the expressive power to encode such a statement. A particle has a trajectory but it has no statement on the sensation of such a trajectory. And even if physics did have the expressive power it would say nothing about the reality of atoms without evidence constraining the relevant parameters. So we shouldn’t accept the claim “atoms have no experiences” or its negation when trying to understand the world. Both participants in the dialogue accept this without question and I don’t think either of them is justified in doing so.

I get that poetic naturalism is kind of this bridge between more continental philosophical views of reality and analytic ones, but I think it’s not really a compromise at all from what I’m reading here. It’s fully committed to naturalism and the more “experiential” aspects are relegated to being a semantic choice for the encoding of our particular naturalistic theory. I don’t think that’s fair since experience is so obviously real to each of us and outside the domain of physics. I’ll read the book before committing this impression to anything more than an impression as I’m sure you’ve tackled these ideas in the writing process.

zarzuelazen:

Eh, again, that’s not a good description of physics as it actually is, and your attempts to force parallels between fundamental physics and psychology are as misguided as the early Platonic attempts to map the number of planets to the number of “elements” (Earth, Air, Fire, Water, Life) and to the number of Platonic solids.

One can always invent an infinite number of conspiracy theories that presume that our understanding of the fundamental nature of reality is deeply flawed. We could be in a Matrix-style simulation; we could be brains in a vat; we could be figments of the Red King’s dream from Alice in Wonderland.

The reason we have to stop at the physical world is that it is sufficient to explain all the evidence.

And, even more to the point, if we presume that consciousness is something not accounted by Newtonian Mechanics plus perhaps trivially insignificant bits from Quantum Mechanics, then we’re forced to conclude that everything we think we know about physics is deeply flawed, at the level of equally forcing us to reevaluate whether or not the Earth orbits the Sun.

That’s something that the supernaturalists really don’t fully appreciate. You can trivially independently verify for yourself the basics of Newtonian Mechanics — and, indeed, you should have done so in the lab for a physics (or, at least, general science) class while you were in school. It’s not that much work to extend those personal-scale observations to the point that you can have overwhelming confidence that Newtonian Mechanics accounts for all the motion around you. And it’s also well within reach of the amateur to independently confirm the basics of chemistry, astronomy, biology (including Evolution), and other branches of science.

When you put all the pieces together, the inevitable conclusion is that there’s no room to fit anything else, especially when it comes to cognition.

Put most simply, your claim that physics can’t account for cognition is a claim of a perpetual motion machine. Your cognition must surely be responsible for work you might perform, such as lifting a weight. We are therefore left to conclude that either your cognition can be fully accounted for in the energy budget, or else that conservation is not preserved. But conservation is the single-best-evidenced theory we have, and no observation of any biological system has ever even hinted at a violation of conservation.

So, again. We might have a rather fuzzy picture of the dynamics of the interior of the Sun, but that doesn’t mean that we should conclude that the Sun is powered by rainbow faery farts; similarly, we have a fuzzy picture of the dynamics of the interior of the brain, but that doesn’t mean that we should invent new physics to account for cognition.

Cheers,

b&

James Cross:

That’s a non sequitur resulting from a flawed analogy.

We do expect that a Macintosh computer should be able to fully simulate a Windows computer (with certain caveats about resource availability and performance). That’s one of Alan Turing’s deep insights: that any computing device that implements a certain bare minimum number of functions is logically equivalent to any computing device of any complexity and sophistication, up to the limit of its memory and speed. And, of course, we have an entire industry built upon that principle. VMware is perhaps the largest competitor in that market today, but IBM mainframes back in the dinosaur age were all virtualized systems.

The materialist claim is no more and no less than one that Alan Turing was right.

Incidentally, the supernaturalist claim that cognition is not a physical phenomenon is equivalent to a claim that the Halting Problem can be solved, which, in turn, works out to a claim that one can build a perpetual motion machine.

Me?

My money’s on Turing….

Cheers,

b&

Daniel Kerr,

That’s a prejudicial characterization, but essentially correct.

Whatever “mental properties” you might be referring to, we know they are not fundamental to the Universe. That’s not to say they’re not real; temperature isn’t fundamental, either — and neither is water. But we know that temperature is “merely” a characterization of the average kinetic energy of a substance’s molecular structure (loosely), and that water is a compound of hydrogen and oxygen — each of which, in turn, are mostly made of quarks, which might, themselves, maybe, be made of strings.

The naturalist position is that cognition is a particular form of computation and that we no more need to invent new physics to explain our thoughts than we do to explain the functioning of our smartphones. That doesn’t mean that cognition isn’t something amazing and delightful and powerful; just that it’s the same type of phenomenon as everything else we humans typically directly experience.

And, really — wouldn’t it be most peculiar for the parts of us that experience the world to be so radically different from the rest of the world? And isn’t that representative of an extreme example of the same type of self-centered hubris that once caused us to conclude that the Earth is the center of the Universe and that humanity was the crowning glory of the creative work of the gods?

Cheers,

b&

Ben Goren said:

Consciousness itself is emergent for sure, no new physics would be necessary as a description. But if the redness of seeing the color red is to be included in poetic naturalism, it would only be a description. The idea seems to deny that this qualia should be included in any serious view of the world. I have no problem accepting science shouldn’t contain a statement on it, but poetic naturalism applies to a general view of the world and not just our science.

I don’t think it’s a good assumption that these “mental” properties emerge from physical objects that lack experiences which could also loosely be labeled as “mental” properties. We don’t know how atoms experience their existence, if there is even qualia associated with that. It could be that consciousness emerges as a combination of qualia associated with every physical object/interaction. We simply don’t know if “redness” is emergent from something lacking any kind of experience or if it is emergent from a collection of physical objects each with their own set of “mental” properties. In the analogy with temperature I’m saying that temperature requires a collection of particle velocities to emerge and mental properties might require such a combination of qualia themselves. I’m not taking a stance here one way or the other, I’m highlighting the possibility of it and poetic naturalism seems to firmly exclude this possibility in its ontology.

Daniel Kerr:

I’m not sure what you’re aiming at with this.

First, all science is descriptive. When I write that the kinetic energy of an object is equal to the product of half its mass and the square of its velocity, I’m describing the phenomenon. Of course my description isn’t the actual kinetic energy of the object; how could it be otherwise? And why would you expect otherwise with descriptions of cognitive phenomena?

But if you mean that the experience of redness is itself descriptive of the properties of the thing you’re looking at…well, again, isn’t that what one would expect? A red rose doesn’t have some essential property of redness that gets magically reduplicated in your mind; rather, the petals reflect substantially more light with wavelengths clustered around 650 nm or so and longer, which stimulates the “L” photoreceptors in your eye much more than they do the “M” or “S” photoreceptors. That gives you a perception, a description, a representation, of the rose as being red — but it’s not putting the redness of the rose literally in your eye!

“Qualia” are a superbly ill-defined concept. And, as it turns out, completely unnecessary.

Indeed, on the subject of color…the spreadsheet linked to on this page:

http://www.cie.co.at/index.php/LEFTMENUE/index.php?i_ca_id=298

quite literally has all the information you need to explain human perception of color — at least, with more fidelity and completeness than even most graphic artists ever deal with.

If the “qualia” of color is mysterious to you, it can only be because you literally don’t know the first thing about color science — and yet, color science is an incredibly deep and well-developed field, and the foundation of the modern electronic display (including TV) and digital camera and color printer industries.

Indeed, if the aim is to cast doubt on the ability of science to explain cognition, alluding to any purported mysteries about color perception is about the worst tactic you could take. It’s like saying Newton can’t be right because we still haven’t identified on the map the land where the Sun goes during the night, let alone sailed a ship across the ocean to the land of the Sun.

Cheers,

b&

Ben Goren,

You say that all science is descriptive and yet implicitly accept the description is capable of emulating the phenomenon. It’s one thing to claim the description isn’t itself the object, that’s obvious, but I’m saying we need to go one step further, it’s not even capable of emulating the object. It’s just a highly detailed drawing, it’s not a duplicate. Let’s imagine a world where science isn’t done just by humans, but any kind of conscious being we might imagine. They may have completely different sensory inputs or completely different mental architecture. If such a being does not engage the world through sight or respond to light in anyway along its recent evolutionary history, the colorimetric table you’ve provided provides them with no insight on the redness of red. They do not have the apparatus to experience it, it can only be a description to them and something they can never observe “directly.” With that table, however, they could possibly build a measuring device that does and outputs information they do have the sensory capacity to observe “directly.” This does not substitute for seeing in anyway whatsoever. It simulates sight but it does not emulate sight.

I put “directly” in quotes to highlight that isn’t truly direct, as you’ve already pointed out. The perception of redness occurs in the apparatus of our brain responsible for processing vision. Any object which is red does not intrinsically have redness. Redness is a result of the complex brain chemistry/neurology in representing the light reflected off such an object. This is the qualia, not the color of the object, but its mental representation. It’s completely hardware specific, a completely different brain circuitry for processing visual information would most likely not result in the same sensation.

Anybody who’s familiar with late incident cerebral achromatopsia knows that the entire sensation can be completely lost when the parts of the brain responsible for the representation of color is destroyed. What’s strange about this condition is that if the damage is slight, sensory neurons responsible for distinguishing color can still be completely intact. What fails is the synthesis of color’s representation, so the qualia of color is completely lost to those inflicted. Depending on where in the pathway the damage occurs, the result can be something black and white, or grayscale, or if the damage is further downstream say at the point where the color signals are co-processed into a single representation, you get something completely different. This was the case with Jonathan I. in the “Colorblind Painter” by Oliver Sacks in “An Anthropologist on Mars.” Jonathan I. has complete knowledge of color and can describe it as perfectly as any other color seeing person, but he is a zombie when it comes to his experience of it after his brain damage. Specifically Jonathan was experiencing the direct output of V1 in his visual cortex and V4 was not functioning correctly. His qualia was neither colorblind or colored as a result. This example illustrates difference between a description and an experience. You believe the experience can be completely reducible to the description but I bet Jonathan I. would have an issue with your position. More to the point neither you or I can understand his sensation as we don’t experience our direct V1 outputs at all either. We understand the description just fine but no description of the experience allows you to imagine/emulate that experience.

Despite these points you dismiss qualia as unnecessary, which means you have two possible responses:

1) Understanding how another apparatus experiences a representation of its sensory inputs is not necessary except at a descriptive level.

2) It is possible for science to explain how another apparatus’s representation of its sensory inputs can be perceived without duplicating the apparatus for the observer.

Obviously the second case is cheating because then you simply are experiencing the phenomenon yourself and not relying on a description. An example of this kind of cheating also comes from Oliver Sacks in “The Mind’s Eye,” where he has a chapter devoted to stereoscopic vision, the ability to perceive depth from binocular input, which not every person has. He describes woman whose eyes lacked the neuromuscular development to position themselves for stereoscopic vision but late in life gets glasses which provide an offset and allow her to experience stereoscopic vision for the first time (and develop the musculature herself). Before doing so she, like you, was convinced the description of stereoscopic vision in its entirety was enough for her understanding of the phenomenon. She had studied it professionally in some capacity if I recall correctly. However as you can imagine, despite the experience being 100% consistent with the description she had in her mind, she learned she had no understanding of the sensation behind the experience until she experienced it herself.

We can accept science is purely descriptive and that’s all it can aspire to be, but it’s arguable to claim that’s all that is necessary. In a world where our brains might be interfacing with new inputs neurologically in the future, I would say qualia is necessary. I would argue it’s necessary even now but we take it for granted since we all share roughly the exact same sensory apparatus except in a few limiting cases of disability such as the examples I cited.

My original post took all of those points for granted and merely generalizes the “apparatus” of our brains to any subset of an interacting system. I posit that if this is the case for brains, it maybe for the case of a particle with kinetic energy to have its own “sensation” too. We simply cannot dismiss the possibility especially if you accept such probing is immune to scientific inquiry.

Daniel

Daniel Kerr:

Daniel, you’re conflating two entirely different things.

Yes, of course. Science is descriptive. But part of that description is of symmetries, of things that are identical.

All electrons are interchangeable, for example. You can strip an electron off of a water molecule and graft it onto an iron atom and you’ve no way of knowing after the fact that that’s what happened.

Mathematics has similar ideas. It matters not whether you multiply four by two or two by four; the result is still eight, and the two terms are considered identical.

The same is true in computer science. Use big-endian or little-endian byte order and it makes no difference, so long as you’re consistent.

Proposing that cognition is a Turing-complete form of computation is no more radical than proposing that extra-solar planets follow elliptical orbits ’round their stars.

But how is this in any way relevant or at all a stumbling block?

No human has ever personally experienced Lorentzian contraction. Some have seen video simulations of the phenomenon, and had similar emotionally-charged reactions to the experience. But nobody thinks that we therefore don’t properly understand Relativity, or that the only way to understand Relativity is to experience it directly, or that physics is incomplete until it includes an explanation for every intimate personal experience of it.

Yes, of course. Direct personal experience adds new dimensions and richness to understanding. How could it be otherwise?

But bringing that up in this context has as much bearing as the beauty of last night’s sunset does to the fact that the heliocentric model of the Solar System is correct. I mean, yes, certainly, the Sunset last night was beautiful…but what’s that got to do with the price of tea in Japan?

Cheers,

b&

Ben Goren,

You’re evaluating my position as it applies to science. I think you and I are in full agreement that these points do not pertain to how we do science for the simple reason that we believe they can’t. The goal of a description is that there is some apparatus out there that can make correct predictions about its own sensory input from the world based solely on the description it is provided. Science accomplishes just that. Science’s inability to present the experience of such events doesn’t make our theories within science incomplete, it simply makes science an incomplete description of our universe. I think this is logically obvious from the fact that science is a description and all descriptions are inherently reductions.

The lens my argument is being made through is that of philosophy. Poetic naturalism seemingly implies that science is the most complete description we can have and its expression is an artistic free parameter. I’m saying that all of the points I’ve brought up are inconsistent with this worldview as they lie outside the realm of scientific inquiry. Jonathan I.’s experience cannot be probed by any method we have, we simply lack the apparatus (or specifically the configuration of our own apparatus) to really imbue the description of his reality with sensation. We can exclude these points I raised from our science, sure, but we can’t dismiss them from our philosophy. Clearly the description does not capture the experience, so no picture of the universe is complete without that. I’d personally argue that such a description is impossible and science is the most consistently, complete we could strive for.

I think there are forms of naturalism that do encompass qualia, but poetic naturalism doesn’t seem to be capable of doing so. My read on Sean’s intentions is that he wants his brand of naturalism to encompass these more “lofty” points of view. I’m pointing out that based on the presented material so far, it doesn’t seem like it can.

Daniel

Ben

“We do expect that a Macintosh computer should be able to fully simulate a Windows computer..”

MacIntosh – Hardware

Windows – Operating system

Windows computer – Any computer running Windows?? Which could be a MacIntosh

Are you saying

A MacIntosh [hardware] should be able to simulate a Window computer [hardware, maybe a MacIntosh]

Or are you trying to saying a MacIntosh can run Windows?

The first doesn’t make much sense and the second isn’t at all profound.

You’re also sort of mixed up about IBM systems in the dinosaur age. I know because I am a dinosaur.

They had three main operating systems:

MVS

DOS\VSE

VM

The VS in the first two had” virtual” as part of the name but it is related to the memory management. Not virtual machines.

Big companies ran MVS. Small ones tended to run DOS\VSE. Some companies ran VM either on test or development systems or to scale up DOS\VSE which had limitations. VM may be what you are thinking of but it wasn’t run on “all” systems.

But none of this has much bearing on the discussion at hand other than the fact that computers exist and Turing provided the logical and mathematical basis for them. Whether you are simulating a glass of water with a MacIntosh or a Windows computer or an IBM mainframe water won’t come out of the hardware.

Consciousness, if we insist on using a computer analogy, is more like firmware – hardware and software in one bundle – and it runs in brains and nervous systems.

Daneil and zarzuelazen ,

Take a look at Donald Hoffman

Abstract

Despite substantial efforts by many researchers, we still have no scientific theory of how brain activity can create, or be, conscious experience. This is troubling, since we have a large body of

correlations between brain activity and consciousness, correlations normally assumed to entail that brain activity creates conscious experience. Here I explore a solution to the mind-body problem that starts with the converse assumption: these correlations arise because consciousness creates brain activity, and indeed creates all objects and properties of the physical world. To this end, I develop two theses. The multimodal user interface theory of perception states that perceptual experiences do not match or approximate properties of the objective world, but instead provide a simplified, species-specific, user interface to that world. Conscious realism states that the objective world consists of conscious agents and their experiences; these can be mathematically modeled and empirically explored in the normal scientific manner.

http://www.cogsci.uci.edu/~ddhoff/ConsciousRealism2.pdf

It may sound completely crazy but there’s more to it than means the eye.

I’d just like to point out on the topic of Turing computability is a bit reductionist in that it completely ignores the hardware. It has become convention to interchangeably treat axiomatic proof systems as Turing machines but the former offers an insight I think the latter hides too effectively. An axiomatic system has several possible models that realize it, and if this system can express predicate logic then we know by the Incompleteness theorem there are statements in this system that are not consistently evaluated between different models despite every model being consistent with the axiomatic system.

In this analogy a Macintosh or Windows machines would be different models for the Windows syntax. Every computable statement evaluated between them should be consistent, but the details of those models’ execution of the syntax are probably not the same at all. In particular any statements that entail how the Windows syntax is actually evaluated (most such statements should be uncomputable from within Windows as they should fall under the halting problem) are free to vary between them. In this sense only the syntax is faithfully simulated, but not the hardware. In this analogy the claim is that consciousness is not just a syntax but has model specific features.

Provided that the hardware of the Windows machine can be encoded by a Turing complete language, then one could simulate a Windows machine running Windows. One would find that the simulated hardware should have the same model features as the actual Windows machine, but the Macintosh simulating it would be even further removed from the Windows machine. The way the Macintosh executes the simulation on its hardware would resemble nothing like how the actual Windows machine runs Windows on its hardware. Taken to its logical extreme a faithfully simulated brain would be conscious from an observer in the world of the simulated physics, but the simulated physics isn’t itself conscious from our point of view and thus neither is the simulated brain. These features are lost in the representation. The model matters, a proof theoretic system isn’t enough of a faithful representation, how that syntax is implemented matters in the real world. Science only cares about the syntax because that’s all it can evaluate. Science explicitly uses other models to represent the universe’s syntax (specifically subsets of the “actual” model) so there are features of the universe it cannot capture that are model specific.

Daniel

James,

Hoffman’s ideas is one of the ones I had in mind when I said that it’s possible even atoms have could have “mental” experiences. I haven’t worked through the arguments in his paper to fairly represent them and I think my own views differ quite a bit. His particular view entails a subjective interpretation of quantum mechanics for example, that particles only take on values when observed and those values depend on the observer. A measurement correlates an eigenstate, belonging to the measurement device’s eigenbasis when interacting only with the environment, with the measured object’s state at the time of the interaction. The state of the measurement device is just as real/objective as the state of the measured object, so I wouldn’t believe the measurement device’s state is an observer-dependent phenomenon. The act of the correlation inherent to the measurement is probabilistic no matter how you look at it.

Daniel

Ben:

“Eh, again, that’s not a good description of physics as it actually is, and your attempts to force parallels between fundamental physics and psychology are as misguided as the early Platonic attempts to map the number of planets to the number of “elements” (Earth, Air, Fire, Water, Life) and to the number of Platonic solids.”

We cannot presuppose in advance what reality consists of! The very word ‘physical’ itself is a concept in the human mind. If you start with the axiom that ‘everything must be explained in terms of reductionistic physics’, then it’s no surprise that that’s the only answer you’ll ever get out 😉

Ben:

“One can always invent an infinite number of conspiracy theories that presume that our understanding of the fundamental nature of reality is deeply flawed. We could be in a Matrix-style simulation; we could be brains in a vat; we could be figments of the Red King’s dream from Alice in Wonderland.”

But in fact there are a number of very intelligent and serious philosophers of science that take the ‘reality is a simulation’ (brain in a vat) idea very seriously! (Nick Bostrom for example). See my previous paragraph. We can’t presuppose in advance what reality is, and even our conception of ‘physical reality’ is in some sense a ‘choice of vocabulary’.

My suggestion is that you take off your physics hat for a moment and put on your computer programmer hat. Imagine you are trying to write a computer program to model (or ‘simulate’) something.

You can’t presuppose in advance what sort of classes (or ‘ontology’) you are going to use in order to perform the simulation. How various data objects in your program get labelled depends simply on how useful you (the programmer) find these labels to be. Now imagine that the ‘physical world’ is just another label you may or may not decide to use in your model.

You may protest that ‘psychological labels’ are not reality, but you don’t know in advance what reality is. Only the theories or models you use (which must by necessity involve some psychological labels or ‘concepts’) can guide you.

Ben:

“And, even more to the point, if we presume that consciousness is something not accounted by Newtonian Mechanics plus perhaps trivially insignificant bits from Quantum Mechanics, then we’re forced to conclude that everything we think we know about physics is deeply flawed, at the level of equally forcing us to reevaluate whether or not the Earth orbits the Sun.”

I don’t agree. There a big difference between the brain and nearly all the other physical objects we can see. The brain is far more complex! Science as we know it has only begun to study such highly complex objects. Most physics to date has only been concerned with low-complexity objects.

It might be that there’s a complexity threshold where for very complex objects we need entirely new types of description to explain what’s going on, or even that the lower-level laws are over-ridden by new laws which appear under these high-complexity conditions!

If I may suggest an analogy, imagine the differences between water, ice and gas. If you only ever look at water at room temperature, you might be surprised that your normal descriptions of water fail at very low and high temperatures. Turn up the temperature high-enough, and suddenly the behaviour of the water undergoes a ‘phase shift’! It turns into a gas. Turn down the temperature low-enough, and again you see another big ‘phase shift’, the water has turned into ice.

Something analogous to that could be the case for very high-complexity objects like the brain. In the analogy, imagine that the ‘physical world’ is like water, and consciousness is like ‘ice’. Now imagine that ‘complexity’ is analogous to ‘temperature’.

Physics may appear to be working normally for low-complexity objects (like the sun), but then suddenly, for very high-complexity objects (like the brain) there’s a ‘phase shift’ (analogous to turning water into ice), and you need entirely new levels of description to explain what’s going on.

I’m not suggesting anything supernatural here. Ice , for example, is still , in some sense ‘composed of water’. And, by analogy, I agree that the mind is definitely composed of physical processes. But sill, new levels of description (including ‘mental properties’) may be in fact be needed to explain the mind.

Conclusion: Science has not yet explained consciousness. The big difference between the brain and other physical objects that science has studied is the extremely high complexity of the brain. It *may* turn out to be the case that all the processes of the mind can in fact be construed as ‘physics’. However, from the computer programmers perspective (imagine we are a ‘brain in a vat’) we are trying to create models (simulations) of what we see, so we cannot presuppose in advance what reality is. The only criterion we that can guide us is how useful the ‘labels’ we use are. And ‘the physical world’ is just another label.

Daniel Kerr:

In that case, I think you’re making the typical philosophical mistrake of pushing a question far beyond what is reasonable and failing to recognize that that’s a sign of incoherence, not of something worth further pondering.

When it comes right down to it, what you’re asking for is no less than for you to directly personally experience what another individual experiences, and you will accept nothing less for an answer. You don’t merely want an explanation for consciousness in others; you want an experience of consciousness in others. You wish to subsume the “qualia” of other individuals into your own.

I could go on at length as to the unreasonableness and absurdity of such a position, but it should hopefully follow fairly obviously simply from my identifying it as what you’re demanding.

Cheers,

b&