Hidden in my papers with Chip Sebens on Everettian quantum mechanics is a simple solution to a fun philosophical problem with potential implications for cosmology: the quantum version of the Sleeping Beauty Problem. It’s a classic example of self-locating uncertainty: knowing everything there is to know about the universe except where you are in it. (Skeptic’s Play beat me to the punch here, but here’s my own take.)

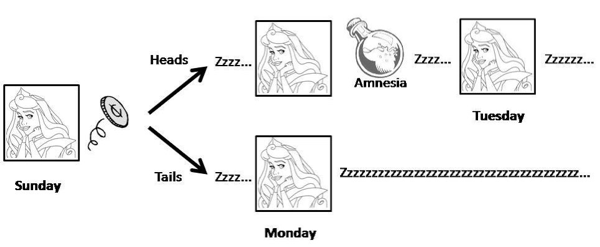

The setup for the traditional (non-quantum) problem is the following. Some experimental philosophers enlist the help of a subject, Sleeping Beauty. She will be put to sleep, and a coin is flipped. If it comes up heads, Beauty will be awoken on Monday and interviewed; then she will (voluntarily) have all her memories of being awakened wiped out, and be put to sleep again. Then she will be awakened again on Tuesday, and interviewed once again. If the coin came up tails, on the other hand, Beauty will only be awakened on Monday. Beauty herself is fully aware ahead of time of what the experimental protocol will be.

So in one possible world (heads) Beauty is awakened twice, in identical circumstances; in the other possible world (tails) she is only awakened once. Each time she is asked a question: “What is the probability you would assign that the coin came up tails?”

(Some other discussions switch the roles of heads and tails from my example.)

The Sleeping Beauty puzzle is still quite controversial. There are two answers one could imagine reasonably defending.

- “Halfer” — Before going to sleep, Beauty would have said that the probability of the coin coming up heads or tails would be one-half each. Beauty learns nothing upon waking up. She should assign a probability one-half to it having been tails.

- “Thirder” — If Beauty were told upon waking that the coin had come up heads, she would assign equal credence to it being Monday or Tuesday. But if she were told it was Monday, she would assign equal credence to the coin being heads or tails. The only consistent apportionment of credences is to assign 1/3 to each possibility, treating each possible waking-up event on an equal footing.

The Sleeping Beauty puzzle has generated considerable interest. It’s exactly the kind of wacky thought experiment that philosophers just eat up. But it has also attracted attention from cosmologists of late, because of the measure problem in cosmology. In a multiverse, there are many classical spacetimes (analogous to the coin toss) and many observers in each spacetime (analogous to being awakened on multiple occasions). Really the SB puzzle is a test-bed for cases of “mixed” uncertainties from different sources.

Chip and I argue that if we adopt Everettian quantum mechanics (EQM) and our Epistemic Separability Principle (ESP), everything becomes crystal clear. A rare case where the quantum-mechanical version of a problem is actually easier than the classical version.

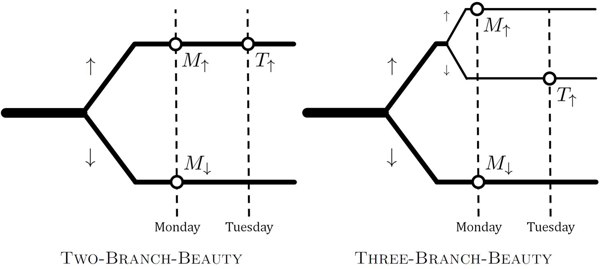

In the quantum version, we naturally replace the coin toss by the observation of a spin. If the spin is initially oriented along the x-axis, we have a 50/50 chance of observing it to be up or down along the z-axis. In EQM that’s because we split into two different branches of the wave function, with equal amplitudes.

Our derivation of the Born Rule is actually based on the idea of self-locating uncertainty, so adding a bit more to it is no problem at all. We show that, if you accept the ESP, you are immediately led to the “thirder” position, as originally advocated by Elga. Roughly speaking, in the quantum wave function Beauty is awakened three times, and all of them are on a completely equal footing, and should be assigned equal credences. The same logic that says that probabilities are proportional to the amplitudes squared also says you should be a thirder.

But! We can put a minor twist on the experiment. What if, instead of waking up Beauty twice when the spin is up, we instead observe another spin. If that second spin is also up, she is awakened on Monday, while if it is down, she is awakened on Tuesday. Again we ask what probability she would assign that the first spin was down.

This new version has three branches of the wave function instead of two, as illustrated in the figure. And now the three branches don’t have equal amplitudes; the bottom one is (1/√2), while the top two are each (1/√2)2 = 1/2. In this case the ESP simply recovers the Born Rule: the bottom branch has probability 1/2, while each of the top two have probability 1/4. And Beauty wakes up precisely once on each branch, so she should assign probability 1/2 to the initial spin being down. This gives some justification for the “halfer” position, at least in this slightly modified setup.

All very cute, but it does have direct implications for the measure problem in cosmology. Consider a multiverse with many branches of the cosmological wave function, and potentially many identical observers on each branch. Given that you are one of those observers, how do you assign probabilities to the different alternatives?

Simple. Each observer Oi appears on a branch with amplitude ψi, and every appearance gets assigned a Born-rule weight wi = |ψi|2. The ESP instructs us to assign a probability to each observer given by

![]()

It looks easy, but note that the formula is not trivial: the weights wi will not in general add up to one, since they might describe multiple observers on a single branch and perhaps even at different times. This analysis, we claim, defuses the “Born Rule crisis” pointed out by Don Page in the context of these cosmological spacetimes.

Sleeping Beauty, in other words, might turn out to be very useful in helping us understand the origin of the universe. Then again, plenty of people already think that the multiverse is just a fairy tale, so perhaps we shouldn’t be handing them ammunition.

Ramanujan,

“The main halfer argument is that when she awakens she gets no new information. But she does: by awakening she learns that the current situation is not T/t. In the modified puzzle, she gets the exact same information but in a different way.”

That is indeed what they claim, but the error comes from failing to realize that information loss (not just gain) affects conditionalization. Consider that on Sunday, she knows that “It is before the effects of the toss on SB have been realized” (I will call this information “B”). But on each awakening, she does not know B. If the odds for tails vs. heads are 1:1 with B, then without B, the odds need to be multiplied by p(B|H)/p(B|T). And (assuming the principle of indifference), that multiplier is equal to 0.5/1.0. Those probabilities are derived from background information which she retains throughout the experiment, rather than information gained on waking. So the new odds are tails:heads = 1:2, or 1/3 probability for tails. Now, if she is told B after the interview, she can reverse that calculation and recover the original odds.

Ah, I see your point Richard. I’m treating the days as random variables for the experiment and I did not condition them on interviews. The way I see it, the experiment is carried out on 1 of 2 days, and at any given time, it could be one of those days. Perhaps it makes sense to condition them on the interview them just to clarify them.

Hal, I’m not suggesting you interview the interviewers, I’m suggesting you build the full probability sample space before you collapse it down to a conditional probability.

Nothing more to add

I have had an interesting exchange with another blogger, a proponent of 1/2, about my delayed-information experiment four comments above. He agrees that before we get the information that it is or is not Tuesday+tails, the conditional probability P(tails | Tuesday+tails) = 1/3. The definition of P(A | B) is that if we are given the additional information that B is true, then the prior P(A | B) becomes the new P(A). He argues that this is not true, that P(A | B) can change retroactively when we learn that B is true. I believe that this is simply not true, ever, that it runs directly counter to the definition of P(A | B).

The definition of conditional probability is P(A|B) = P(A&B)/P(B), I don’t think you can get any clearer than that. It never changes whether A or B is true or not, it doesn’t “collapse” any more than “if” statements “collapse” in modus ponens.

typo in previous post: P(tails | NOT Tuesday+tails) = 1/3

Very late to the party here, but last week I was discussing this with Sean at the Quantum Foundations conference, so I can’t resist throwing in my 2 cents.

I agree with Joe that the “phenomenalist” position is the correct one. It’s worth noting that, according to wikipedia, the phenomenalist position was originally articulated in a post by “Alice Atlas (Zorti Zandapheri)” (that’s what it says on the author’s facebook page) on the rationalist website Less Wrong: http://lesswrong.com/lw/32o/if_a_tree_falls_on_sleeping_beauty

However, I think Joe misstates Alice’s main point. She did not argue that the “thirders” are correct, but rather that the answer to the question “What probability should Sleeping Beauty assign to the coin having come up tails?” depends on what Sleeping Beauty is going to do with this probability. Sean and Joe believe that the betting protocol (outlined by Joe) is obviously what was meant. But other meanings are possible. For example, after many runs of the experiment (with no betting), Sleeping Beauty could decide to look at the experimenter’s logbook of coin tosses, see what fraction of those came up tails, and compare her probability assignment to that fraction. (The first time I heard about this problem, this is what I thought Sleeping Beauty should do.) This protocol leads to the “halfer” position. Alice points out that there would be no controversy if the appropriate meaning of “Sleeping Beauty’s probability” was clearly spelled out at the beginning.

Way to go Alice! You have, in my opinion, clearly outthought a whole bunch of professional philosophers, none of whom (as far as I know) made this key point.

The problem statement, as far as I know, doesn’t ask SB for the probability, it asks her what her belief is for the coin that determined her being asked this question had turned up heads.

Daniel, read the original post. Sean writes:

But as Alice Atlas pointed out, there are several possible (more precise) versions of this question. Here are two (quoting Alice):

(Here I’ve added the text in brackets to further improve the clarity.)

I think that almost everyone would agree that in the first more-precise version, guessing “heads” gets Beauty twice as much money (on average) as guessing “tails”. I also think that just about everyone would agree that the answer to the second more-precise version is “one half”.

So I agree with Alice Atlas that the whole problem is simply one of imprecise language.

Mark,

They’re not “more precise” versions of the question: they’re different questions and thus different experiments. The first one would require S.B. to calculate a conditional probability representing her own state of knowledge, as in the original experiment, and the second one would require her to ‘calculate’ a probability representing the experimenter’s (or any other ‘external’ observer’s) state of knowledge.

I believe the appropriate meaning of “Sleeping Beauty’s probability” is clearly spelled out at the beginning and I’m afraid I don’t see any outthinking of philosophers in that Less Wrong article. In all these baroque rationalisations of the “halfer” position (or worse!) all I see is errors and misconceptions – like that “no new information” one, the failure to (consistently) condition, the confusing of a probability of a coin flip outcome event with a coin ‘propensity’ probability, the failure to distinguish between an inference and a meta-inference,… Instead of [an attempt to justify why] a simple and correct conditional probability calculation [is wrong] we’re given modifications to the S.B. Problem accompanied by long-winded appeals to decision theoretic or phenomenalist requirements or whatever. In that Less Wrong article this sort of folly leads to the rejection of [the use of] probability theory in its full generality – as a theory of events and representations of (observer/information-dependent) states of knowledge.

I agree with Mark that there is some ambiguity. For example, the answer to “What is the probability you would assign that the coin came up tails?” should, it seems to me, revert to 1/2 as soon as SB starts to get out of bed, since at that point she knows the experiment is over, and whether or not she was awakened previously, she has just been awakened as part of the experiment for the last time, which happens once (per experiment) for heads and once for tails.

The model that I use (because it seems most natural to me) is:

The probability that the coin landed heads and SB will be awoken for the first time is 1/2.

The probability that the coin landed heads and SB will be awoken for the second time is 1/2. (Both events will always occur for heads.)

The probability that the coin landed tails and SB will be awoken for the first time is 1/2.

The probability that the coin landed tails and SB will be awoken for the second time is 0.

Therefore when SB wakes it could be one of three different events which have equal probabilities, so the probability she should assign to any one of them should be (1/2)/(1/2+1/2+1/2) = 1/3. However once she knows the experiment is over (but before she discovers how many days the experiment has taken) then her last awakening is is one of two different events with equal probabilities.

Mark, Sean was paraphrasing the wikipedia article which asks about belief. I think it’s fair to say that the problem is trivial if it’s asking SB’s probability assignment of a coin flip in general and not her bias in sampling this particular coin flip. Supposing all variants are probably asking the same question, the thirder version of the question is consistent across all variants, while the halfer is not. In light of this, I would phrase your more precise question as follows:

Each interview consists of one question, “What is the limit of the frequency of heads [in the experimenter’s logbook in which the coin flip results are indexed by the interviews of SB] as the number of repetitions of this experiment goes to infinity?”

Clearly tails would be double counted in such a log book even though one experiment is responsible for both entries. If the question isn’t asking this, then it’s a trick question, but the halfer arguments in this comment section are answering the above precise version of the question and not your own.

Well it was philosopher David Lewis who first articulated the “halfer” position; Alice was simply summarizing it (and not endorsing it).

If we specify that “Beauty’s probability” is defined by the betting protocol in which bets are made and paid on both days (and Beauty keeps all winnings), then the “thirder” position is validated by a simple calculation, and we’re done.

At that point, the entire argument is about whether or not the original language was clear enough to imply this betting protocol unambiguously. You think it was; I think it wasn’t. But an argument over precision of language is not one I’m very interested in.

Note for clarity: my last comment was in reply to phayes; the comments by JimV and Daniel Kerr were posted while I typing it.

Daniel,

I do not accept your rephrasing; the logbook I had in mind shows the result of the coin flip, as seen by the experimenter (who only flips the coin once for each run). If the coin is fair, on average half the entries are heads and half are tails.

I repeat that, when I first read the SB problem, my instantaneous reaction was that Beauty’s probability should be 1/2, because half the entries in that logbook are tails, end of story. It just doesn’t matter how many times she gets woken up. So you would say that I misread the problem. I would say (following Alice) that greater precision in language would have cleared things up.

Mark, I read the problem the same way as you did initially as Sean posted it, I did not reach the thirder position until I read the wikipedia link and calculated it myself. Again, my “precise” wording of the problem is following wikipedia’s phrasing. Alice’s “precise” wording is of a different question. Both are equally valid. The original “probability” phrasing is vague as it does not specify if its SB’s conditional probability we are finding or the absolute probability. The latter is trivial, so I assume the problem asks for the former. And again, halfers assume the former as well by and large.

And it’s important to recognize that SB’s conditional probability is 1/3 whether she’s betting or not. And that’s because the interview logbook double counts tails. This is the logbook SB has access to, not the experimenter’s logbook. Even still, if the experimenters organized the logbook so that the result of the coin flip was indexed by days, then both heads and tails would be double counted. If we then looked at the subset SB was actually interviewed over, 1/2 of the heads results would not be included. This is SB’s logbook of the experiment.

This is just more experimental evidence that the language of the problem is not unambiguous.

Researching the history of the problem, it’s evolved from the paradox of the absent minded driver, which asks about maximizing a payoff between choices, so I’m not going to fault Sean for restating a problem using vague language!

If on Monday the overwhelming majority of humans in the history of the world see clear Design and even claim to know there is a Creator..

Then on Tuesday atheists enter physics to prove it only “appears” designed..

But on Wednesday find the underlying math is even more designed than appearance..so much that the universe is impossible…

in other words..

When empirical data has lined up with what the entire world says is obvious in all of 3 seconds–and that data was not even a factor in why the world believes there is a God..isnt it the height of irrationality to now suggest there is a multiverse? Thats beyond embarrassing and demonstrates the pathological bias involved.

Hi,

I have some naive layperson questions regarding the multiverse interpretation of quantum mechanic. I’m writing a SF novel and I would like to use this interpretation, but a few points are still not clear…

I don’t understand why we observe interferences. In the sense that if I’m in universe A, where the result of measuring M will give M_A (the value of M in universe A, that’s why we call it universe A in the first place), why would some experiments give me the impression that M is in a superposition of several states? I guess you will say that’s what we observe and this is quantum mechanic dude… But I thought I would ask anyway, in case I’m missing something…

Also, what does this interpretation of QM have to say about Delayed Choice Quantum Eraser Experiment? If I understood it well, this experiment says that a photon (well, a pair truly) correlated with another one (another pair), knows what its buddy is going to experiment, let’s say, 10 seconds before it experiments it. If we assume that the multiverse interpretation of QM is true, what does it have to say about this? How would a parent explains to his children the delayed choice quantum eraser in the scope of the multiverse interpretation? “Listen daughter/son, there will come a time where delayed choice quantum erasers will keep you awake up to late at night, so hear my piece of advise on this topic…”

PS: English is not my first language, so excuse the strange formulation from time to time…