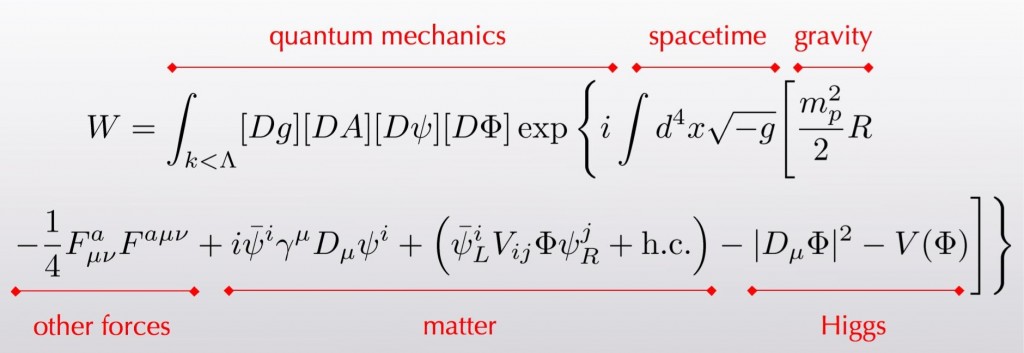

Longtime readers know I feel strongly that it should be more widely appreciated that the laws underlying the physics of everyday life are completely understood. (If you need more convincing: here, here, here.) For purposes of one of my talks next week in Oxford, I thought it would be useful to actually summarize those laws on a slide. Here’s the most compact way I could think to do it, while retaining some useful information. (As Feynman has pointed out, every equation in the world can be written U=0, for some definition of U — but it might not be useful.) Click to embiggen.

This is the amplitude to undergo a transition from one configuration to another in the path-integral formalism of quantum mechanics, within the framework of quantum field theory, with field content and dynamics described by general relativity (for gravity) and the Standard Model of particle physics (for everything else). The notations in red are just meant to be suggestive, don’t take them too seriously. But we see all the parts of known microscopic physics there — all the particles and forces. (We don’t understand the full theory of quantum gravity, but we understand it perfectly well at the everyday level. An ultraviolet cutoff fixes problems with renormalization.) No experiment ever done here on Earth has contradicted this model.

Obviously, observations of the rest of the universe, in particular those that imply the existence of dark matter, can’t be accounted for in this model. Equally obviously, there’s plenty we don’t know about physics beyond the everyday, e.g. at the origin of the universe. Most blindingly obvious of all, the fact that we know the underlying microphysics doesn’t say anything at all about our knowledge of all the complex collective phenomena of macroscopic reality, so please don’t be the tiresome person who complains that I’m suggesting otherwise.

As physics advances forward, we will add to our understanding. This simple equation, however, will continue to be accurate in the everyday realm. It’s not like the Steady State cosmology or the plum-pudding model of the atom or the Ptolemaic solar system, which were simply incorrect and have been replaced. This theory is correct in its domain of applicability. It’s one of the proudest intellectual accomplishments we human beings can boast of.

Many people resist the implication that this theory is good enough to account for the physics underlying phenomena such as life, or consciousness. They could, in principle, be right, of course; but the only way that could happen is if our understanding of quantum field theory is completely wrong. When deciding between “life and the brain are complicated and I don’t understand them yet, but if we work harder I think we can do it” and “I understand consciousness well enough to conclude that it can’t possibly be explained within known physics,” it’s an easy choice for me.

Let me know if I’ve made any typos here, or have gone too far in trying to make things compact. For instance, can I get away without putting a “trace” around the gauge field kinetic term? I don’t want a notational shortcut to undermine my argument and leave the audience believing in God.

Also, the laws underlying the physics of everyday life are not nearly enough to understand all of everyday life; those laws have numerous complex implications that aren’t understood, and aren’t even theoretically understandable from the laws alone because the implications are contingent on historical events … the entire history of the Earth, in some cases. An obvious example is that there is much we don’t understand about physiological processes, especially of the brain … how does spider cognition work, let alone human cognition? What’s the difference between the brains of a smart person, a stupid person, a person in a coma? What’s the difference between the brain of someone who knows the stated law and someone who doesn’t? How is the knowledge stored and how is it made available to behavior? Merely being familiar with the law is not nearly enough to answer these questions.

And the attribute of “understanding” is not a simple one. Properly understood (heh), understanding is about *competence*. That’s why we determine whether students understand something by *testing* them. One might be familiar with the law but have no idea how to apply it … that’s a low level of understanding. Some can apply it only in limited circumstances. Consider understanding a computer language, or understanding how to program … there is a wide range of varying competence.

I could go on and on about the naive reductionism that seems implied here. I’m a physicalist, but I recognize that, while everything is a manifestation of physical law, not all concepts reduce to the physical. You cannot derive the rules of chess from the laws of physics , let alone how to play well.

” the fact that we know the underlying microphysics doesn’t say anything at all about our knowledge of all the complex collective phenomena of macroscopic reality, so please don’t be the tiresome person who complains that I’m suggesting otherwise.”

Oops, I didn’t read that. Well, call me tiresome but that’s what your title *implies*, whether you mean it to or not … making it *false*. “The World of Everyday Experience, In One Equation” — this is just wrong; the world of everyday experience is not in that equation and is not entailed by that equation; that the equation is accurate and that the world of everyday experience is *consistent* with it is a different matter entirely. But in fact the world of everyday experience is largely determined by historical facts … such as the K-T event that allowed mammals to occupy niches formerly held by other organisms that were extinguished … our everyday experience would be very different otherwise, if it’s even meaningful to talk about “us” in such a counterfactual. Or consider the everyday experience of humans 50,000 years ago … very different from our own. So your statement about everyday experience is only true in a very narrow sense … through the parochial view of a physicist.

I think it would be a lot better to say that the laws underlying the physics of everyday life are completely *known*. That would avoid the suggestion that all of the *implications* of the laws are also known, as well as why the laws are what they are.

Sean,

This equation is not an argument against God. The equation simply says that anything is possible and that people will interpret QM as they please.

“There are various ideas where the mechanisms underlying consciousness (in-whole or or-part) consist in areas of physics that are currently not understood (the sub Planckian scale for example). It would be true to say that there is no evidence supporting these theories. But equally, while that area of physics (which also happens to be its most fundamental underpinning) remains beyond our understanding, there is also simply no evidence to the contrary.”

Actually there’s a great deal of evidence to the contrary, as you would know if you studied neuroscience. There is overwhelming evidence that the entire content of consciousness maps to brain processes — the mind is what the brain does.

Talk about David Chalmers and “the hard problem” is really embarrassing in this day and age, like talking about vitalism and suggesting that explaining “life” is some sort of especially hard problem. No competent philosopher of mind takes Chalmers’ zombie arguments and his notions of panprotopsychism seriously anymore.

Hello Sean,

Great formula and nice to look at.

The only thing you seem to ignore (and everyone who is responding) or at least don’t emphasize, is that it only gives you probabilities of things happening, so, for example, it can’t even tell you the future. Stronger even, it says that it is impossible to predict the future! It’s the same as saying that you have a beautiful theory of a person randomly throwing a dice because you know that it has a 1/6 probability for 1, 1/6 probability for 2 etc. This is exactly the same thing your formula is doing. Feynman, being the brilliant and honest physicist he was, clearly saw this and said “Has physics has given up? Yes, physics has given up!”. Also Einstein saw it, couldn’t stand it and even refused to except it. So although “it’s one of the proudest intellectual accomplishments we human beings can boast of” is always inherently very limited.

“This equation is not an argument against God.”

The argument against God is a simple application of Ockham’s Razor … there is nothing that God is necessary to explain (and Goddidit isn’t really an explanation of anything).

“The equation simply says that anything is possible ”

No, it doesn’t say anything like that.

“it can’t even tell you the future”

It constrains the future.

“It’s the same as saying that you have a beautiful theory of a person randomly throwing a dice because you know that it has a 1/6 probability for 1, 1/6 probability for 2 etc. ”

That’s very useful information.

mk,

The equation doesn’t constrain the future anywhere close to what we mean by “everyday experience”. Let’s say someone walk water. It’s in the equation.

I think most scientifically literate people would agree with you, Sean. One might consider though that it is not very useful to summarize the current knowledge by a single equation such as the one above. And this is especially the case when presenting it to lay people, since it adds not one iota to their understanding: it’s just hieroglyphs to them.

Furthermore, since it is impossible to derive most of current day phenomena from that single equation alone (in the sense of the chess analogy), it might be/will probably be seriously misleading to the vast majority of lay people — at least without serious qualifications –, as they are not knowledgeable enough to capture the subtilities and you might easily be misinterpreted as implying that one is able to derive everything from such equation. They will most probably not be able to make the distinction.

It might be better to just say things in simple words: we know the basic constituents of matter and of the laws that determine their behavior. After many years of work by many many people, we have come to think that they provide a satisfactory explanation (often spectacularly so!) of everyday phenomena. But physics (and science in general) is most successful in dealing with simple systems and in Nature complex systems abound. These are hard to analyse and to predict, in the end to understand. Even so, we cannot identify any phenomena, no matter how complex, which we can recognize as being in blatant contradiction with these laws. In some cases, this may be just because we haven’t a clue about the mechanisms involved — such as in the case of consciousness.

“The equation doesn’t constrain the future anywhere close to what we mean by “everyday experience”.”

I didn’t say it did. (Actually, I don’t think that statement is coherent.)

“Let’s say someone walk water. It’s in the equation.”

Try reading the article, especially the bit about being tiresome.

mk,

You’re tiresome.. I think QM is a weak argument against God and now you want me to shut up. That’s normal.

Any chance of getting a nomenclature section on this for the more armchair variety of us who don’t necessarily know what all of those variables are? Also, where are your differentials for those integrals?

Question: Does it have to be One?

I know Physicists do like unification laws, but sometimes individual laws are beautiful in their own right. So, my question is: Can the laws of physics be written as a series of individual equations dealing with specific forces in a way that is equivalent to the unified law, or does theoretical physics discovery operate by Highlander rules(“There can be only one”)?

“You’re tiresome.. ”

Nice personal attack.

“I think QM is a weak argument against God”

Strawman … no one proposed it as such.

“and now you want me to shut up.”

I didn’t say or imply any such thing. Funny though that, despite my never having expressed anything like that, you ceased. I actually would be interested in your explaining what “Let’s say someone walk water. It’s in the equation.” was supposed to mean — it’s rather incoherent on several levels.

“That’s normal.”

For what?

Ah, I think I understand … if someone walks on water, that is consistent with the equation. Well, it depends on the microdetails. As Sean said, ” the fact that we know the underlying microphysics doesn’t say anything at all about our knowledge of all the complex collective phenomena of macroscopic reality”. The equation simply isn’t about things at the level of walking on water … which goes to my complaint that the title is false, more like a provocative newspaper headline that misrepresents the content of the article than like physics.

G,

“Any chance of getting a nomenclature section on this for the more armchair variety of us who don’t necessarily know what all of those variables are? Also, where are your differentials for those integrals?”

The differentials for the path integral (the first one) are inside the [D…] terms, which represent the path integral measure. The differential for the spacetime integral (the second one) is written explicitly, d^4x.

As for the rest (going from left to right): W is the state-sum amplitude, g is the determinant of the metric tensor, m_p is the Planck mass, R is the curvature scalar, F^{a\mu\nu} are the field strengths for the gauge potentials A, \psi^i are the Dirac bispinors, D_{\mu} is the covariant derivative, \gamma^{\mu} are the Dirac matrices, \Phi is the Higgs doublet of scalar fields, V_{ij} are the Yukawa coupling constants for fermions, and V(\Phi) is the symmetry-breaking potential for the Higgs. The boundary condition for the path integral features the generic momentum variable k and the cutoff scale \Lambda. As previously explained, “h.c.” stands for “Hermitean conjugate” of the Yukawa coupling term. The letter “i” which is not an index is the imaginary unit (square root of -1).

You can find definitions (and more) for most of this stuff on Wikipedia. 🙂

Speaking of the “h.c.” term, it would be more correct to put the kinetic term for the fermions inside the parentheses, since it also needs the h.c. contribution if you want to get the fremion-gravity coupling correct. 😉

HTH, 🙂

Marko

Oh, and I forgot — repeated indices are to be summed over (the Einstein convention is assumed).

🙂

Marko

that equation is sheer poetry

humanity akhbar!

I think you have forgotten the second law of thermodynamics…

When naturalists fully comprehend the beautiful and poignant irony of that post, it will be a huge step for the cause. “The heart has its reasons that reason can never know”. Google the full “pensee”, and you will see why Naturalism has a huge gap in helping many people to navigate the universe that presents itself to us.

vmarko,

Thanks, I’ll be sure to look that stuff up on Wikipedia. Also, thanks for the help on those integrals, the change between upper and lower case was throwing me there.

Yeah. This is one sexy equation alright. That hermitian conjugate is staring at me from across the room…

doc c,

science is a way of knowing where we discover/uncover facts. art is a way of knowing where we create meaning. religion is an art.

Einstein grokked with fullness the role of religion & art

(plus, not every BS — belief system — covers and accounts for everything equally well)

variety is the life of spice ;3

Sean,

totally would love to have that equation on a t-shirt :3 I can hear Feynman banging his drums…