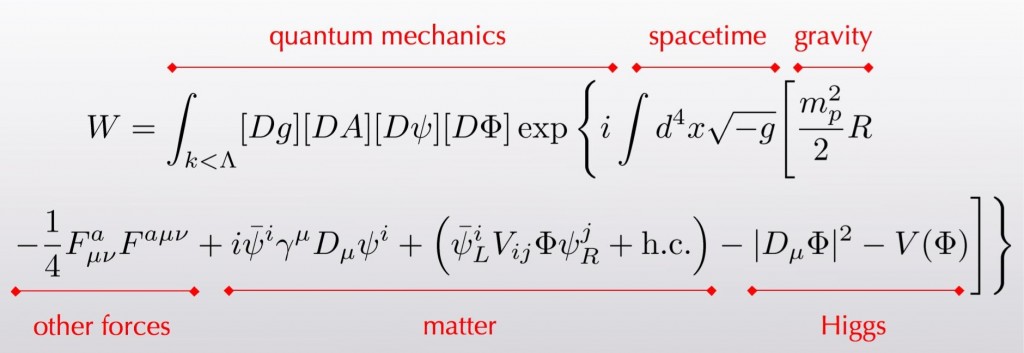

Longtime readers know I feel strongly that it should be more widely appreciated that the laws underlying the physics of everyday life are completely understood. (If you need more convincing: here, here, here.) For purposes of one of my talks next week in Oxford, I thought it would be useful to actually summarize those laws on a slide. Here’s the most compact way I could think to do it, while retaining some useful information. (As Feynman has pointed out, every equation in the world can be written U=0, for some definition of U — but it might not be useful.) Click to embiggen.

This is the amplitude to undergo a transition from one configuration to another in the path-integral formalism of quantum mechanics, within the framework of quantum field theory, with field content and dynamics described by general relativity (for gravity) and the Standard Model of particle physics (for everything else). The notations in red are just meant to be suggestive, don’t take them too seriously. But we see all the parts of known microscopic physics there — all the particles and forces. (We don’t understand the full theory of quantum gravity, but we understand it perfectly well at the everyday level. An ultraviolet cutoff fixes problems with renormalization.) No experiment ever done here on Earth has contradicted this model.

Obviously, observations of the rest of the universe, in particular those that imply the existence of dark matter, can’t be accounted for in this model. Equally obviously, there’s plenty we don’t know about physics beyond the everyday, e.g. at the origin of the universe. Most blindingly obvious of all, the fact that we know the underlying microphysics doesn’t say anything at all about our knowledge of all the complex collective phenomena of macroscopic reality, so please don’t be the tiresome person who complains that I’m suggesting otherwise.

As physics advances forward, we will add to our understanding. This simple equation, however, will continue to be accurate in the everyday realm. It’s not like the Steady State cosmology or the plum-pudding model of the atom or the Ptolemaic solar system, which were simply incorrect and have been replaced. This theory is correct in its domain of applicability. It’s one of the proudest intellectual accomplishments we human beings can boast of.

Many people resist the implication that this theory is good enough to account for the physics underlying phenomena such as life, or consciousness. They could, in principle, be right, of course; but the only way that could happen is if our understanding of quantum field theory is completely wrong. When deciding between “life and the brain are complicated and I don’t understand them yet, but if we work harder I think we can do it” and “I understand consciousness well enough to conclude that it can’t possibly be explained within known physics,” it’s an easy choice for me.

Let me know if I’ve made any typos here, or have gone too far in trying to make things compact. For instance, can I get away without putting a “trace” around the gauge field kinetic term? I don’t want a notational shortcut to undermine my argument and leave the audience believing in God.

I really wish I understood the discussion of the equation. Since it should describe everyday life, I assume it has no need to predict the flat space that comes out of Lambda-CDM alone I take it. I would think that means it should describe small fluctuations in flat space, and not the full GR.

[And I seem to remember flat space in itself is awfully problematic, so Lambda-CDM is perhaps a savior and everyday physics can be thankful for it.]

On to the other side of the coin, the observed and now predicted absence of magic.

@Tony Rtz:

“proving the possibility of a higher state of existence”, “don’t have the slightest understanding of God”.

Any idea of gods so far is based on magic, that energy conservation is broken locally or cosmologically, so that non-physical entities exist and/or do non-physical magic. That is all the understanding necessary, and all what is needed to test magic.

@AI: What is the difference between a predictive efficient description and an “explanation”?

Computer scientist Scott Aaronson has put up an interesting seminar on his blog, on how math have gone from examples to zero-knowledge proofs, modern proofs and their testing (validation) is mapped to manipulation of string symbols.

At the end he asks if mathematics will now go on to understand “explanation”.

[Maybe “explanation” needs knowledge, maybe not. But validation (testing) doesn’t seem to, in principle. It produces knowledge when findings are put in context, of what works.]

@Lord: “Circular definition” is an empirical method, a hypothesis is circular based and tested on its constraints and observations. As long as observation can break theory and move the area, there is no static circularity to get caught up in.

Philosophy, where the notion comes from, is not empirically cognizant, it is about making up conflicting just-so stories from the same basis. All can have their own opinion, which is nice but not empiric.

And I think Carroll explicitly claims that we do know what we don’t know of the basis for the physics of everyday life.

@Foster Boondoggle:

Define “consciousness” testably. If not, why would it be a problem re physics (or magic)? Neuroscience seems to be concerned with awareness and other biological traits.

Chalmers’ make-belief qualia and zombies has to prove themselves, and I don’t see how magic can ever do that.

Jack: “embiggen” is perfectly cromulent. It has always been spelled that way, from its very first use: http://www.backofthecerealbox.com/2012/06/embiggening-your-understanding-of.html

Also for Jack: “Equally obviously” seems correct to me, since the context calls for an adverb, not an adjective. Or it could be changed to “It is equally obvious that…”

Description states what is, explanation states why it is that way. Being able to describe something amounts to knowing, being able to explain something amounts to understanding.

To explain something you have to show how it follows from something else, something already known. An explanation always builds on some other knowledge. For example the structure of the periodic table of elements can be explained in terms of the Pauli exclusion principle (wave function anti-symmetric with respect to exchange) , but the principle itself cannot currently be explained in terms of anything more fundamental and is therefore not understood it is simply known.

So the original statement that “the laws underlying the physics of everyday life are completely understood” is invalid. The correct version would be:

Most aspects of everyday life can be explained in terms of the known laws of natural sciences.

Most instead of all because there are crucial aspects that cannot be explained in terms of anything, the number of dimensions and their properties are one example. Natural sciences in place of physics because explanations of great many aspects of everyday life like evolution or love require more information then is contained in just the laws of physics.

Richard M — Thank you for sharing that article. I am chastened to admit that I didn’t know half of that.

AI — Your restatement of “the laws underlying the physics of everyday life are completely understood” with “Most aspects of everyday life can be explained in terms of the known laws of natural sciences” shows that you really don’t understand what Sean was saying in the first place. Try reading those posts again a little slower.

I don’t know, AI. Google says:

“un·der·stand

/ˌəndərˈstand/

Verb

Perceive the intended meaning of (words, a language, or speaker): “he could usually make himself understood”.

Perceive the significance, explanation, or cause of (something): “she didn’t really understand the situation”.

Synonyms

comprehend – realize – see – apprehend – grasp – perceive”

You seem to be insisting that only the second definition is correct.

Hi Sean, 🙂

“I still don’t understand why saddle points shouldn’t dominate the path integral, by the stationary phase approximation. I understand it in Euclidean quantum gravity, where the true minima of the action dominate. But I don’t see it in the Lorentzian case.”

Ok, the difference between Euclidean and Lorentzian cases can be tricky, and implementation-dependent. I know some QG models where the Lorentzian version is defined by analytic continuation from the Eucliden case (i.e. “Wick-rotated”), and also other QG models where Lorentzian and Euclidean versions are defined quite differently and have little in common.

I agree that a Lorentzian model could be made to work, given an appropriate definition of the path integral, but I think we are still far from a straightforward computation of the effective action. There is always a lot of handwaving involved before one can say that the classical solutions dominate the path integral.

But I guess we’ve beaten this topic enough. 😉

Best, 🙂

Marko

One will need an XXL t-shirt for that equation. Or real fine print.

@MarkS: Your thinking that I am trying to restate, as opposed to correct, Sean’s statement shows that you really don’t understand what I wrote. Try reading those posts again a little slower.

@Richard M: In this context it is indeed the second definition that applies. If you interpreted the statement according to the first definition it would have Sean arguing that physicists know what they mean by their own laws.

Most impressive. I wonder, how far is physics from becoming a monastic discipline, wherein monks study in isolation from mundane society for many years to understand the arcane truths of theoretical physics as discovered by the great minds of previous centuries, and the rest of their lives passing on this received wisdom to the next generation? Is there any future in fundamental physics as an experimental science? Is this the beginning of the new scientistic religion?

No AI, it means Sean is saying that physicists understand what the *Universe’s* laws are (up to the limit where the weird stuff comes in, hence the “everyday” qualfication).

Neil, I like the idea of getting this on a t-shirt.

Imperius, I have no idea why this would make things any different from the way they are now.

What a great post, Sean. I enjoyed this one in a serious way.

Richard: I thought a tattoo on my behind would be more sufficient. I was told by the significant other that it might be a bit too hard to remember written on my own butt.

No Richard, the original statement (“the laws underlying the physics of everyday life are completely understood”) uses the second definition of the term “understand” from your dictionary. The first definition – “to perceive the intended meaning of” something – in the case of the laws of physics means knowing that “a” in “F = m a” stands for acceleration and that it means the change of velocity with time and so on. Clearly not the intended meaning. If you still don’t see it it’s your loss.

Tevong – that’s not the point. This is the point.

Pingback: Why Sean Carroll is wrong « Quantum Moxie

AI, your argument is getting tiresome, so this is the last I will post on the subject. You are taking a very reductionist approach to interpreting the verb, by claiming that the first sense of “understood” means simply that the meaning of each of the symbols in an equation is known. That’s absurd.

If you ask a physicist whether our understanding of gravity changed during Newton’s time, and again with Einstein, I do not think you will get the answer you are hoping for. And the answer they give you will not be because we now know the meanings of symbols we didn’t know the meaning of before (as if the equations had been written out long before Newton but we didn’t know how to interpret them). It will be because we have grasped certain fundamental facts about nature.

Gizelle Janine: Sadly, I guess the world will never see the tattooed rendition.

Richard: I hope you’re right. I’d hate to see the therapist bills I’d be responsible for…

Hi Sean,

I’m interested in why you don’t think that even just classical mechanics (including classical electrodynamics) isn’t enough to describe the world of everyday experience? I grasp your point about a table really being empty space with a smattering of atoms that relies on a quantum mechanical explanation–but it seems to me as though the table’s really being empty space is not really everyday experience (as I recall, it was rather a surprise to turn-of-the-20th-century physicists to find that tables are mostly empty space).

Best,

Toby

Classical mechanics can’t explain many important things, like chemistry.

Imperius: I think you have a point, and I think we’re not too far from having further advances in many fields depend on medical advances in delaying senescence. Of course, most fields have more severe problems than that; but physics has avoided other problem areas well enough that hours-to-mastery vs. productive-hours-remaining is a standout bottleneck.

You have Empiricle and theoretical Scientists working on the understanding of “The Physics of Everyday Experience”. I believe that mathematics is a beautiful language and can explain a multitude of physical processes.But to imply that mathematics can explain everything is not a valid statement. Mathematics requires information and information is infinite.

REA

Sean-

Good point. Embarrassed that it didn’t occur to me, actually. I suppose explaining why things are different colours, too.

“every equation in the world can be written U=0”

Yes, obviously, but not every true proposition about the world is an equation. Some are inequalities and some are logical forms such as conjunctions, disjunctions, and material implications, for instance.