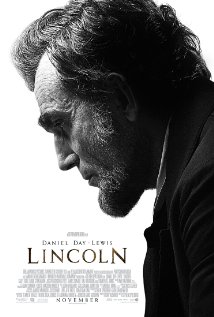

Part of our traditional Christmas celebration is going out to see movies. This year we saw Lincoln, which was even better than I thought it would be. Daniel Day-Lewis is a genius, as you don’t need me to point out, and Tommy Lee Jones was given a substantial amount of scenery to chew. The cast was uniformly excellent, especially Sally Field and David Strathairn, not to mention a nearly-unrecognizable James Spader. As you would expect from a Spielberg film, the pacing and cinematography were outstanding, and the usual Spielbergian sentimentality was almost entirely absent. Tony Kushner’s screenplay was witty, warm, and erudite. Perhaps most impressively, the film managed to make fights over Congressional procedures and vote-wrangling seem action-packed, even when the outcome of the vote was (presumably) known perfectly well to the audience. The movie could have been titled “House of Representatives” rather than “Lincoln,” although that might have had a somewhat depressing effect at the box office.

Part of our traditional Christmas celebration is going out to see movies. This year we saw Lincoln, which was even better than I thought it would be. Daniel Day-Lewis is a genius, as you don’t need me to point out, and Tommy Lee Jones was given a substantial amount of scenery to chew. The cast was uniformly excellent, especially Sally Field and David Strathairn, not to mention a nearly-unrecognizable James Spader. As you would expect from a Spielberg film, the pacing and cinematography were outstanding, and the usual Spielbergian sentimentality was almost entirely absent. Tony Kushner’s screenplay was witty, warm, and erudite. Perhaps most impressively, the film managed to make fights over Congressional procedures and vote-wrangling seem action-packed, even when the outcome of the vote was (presumably) known perfectly well to the audience. The movie could have been titled “House of Representatives” rather than “Lincoln,” although that might have had a somewhat depressing effect at the box office.

You can’t tell a story based on historical events, however, without people comparing your tale to reality — just like science-fiction stories will always be compared to plausible science. My impression is that Lincoln comes out pretty well on the historical-accuracy scorecard, although there are inevitable hiccups. Some of these just seem annoying and unnecessary. At one point Spader’s character mentions that Lincoln’s face appears on fifty-cent pieces; this adds nothing to the dialogue and throws the viewer out of the film, as most people know that living Presidents don’t appear on currency.

Beyond the simple standards of accuracy, an historical film inevitably requires choices of what parts of the story to tell, and which to leave behind. Lincoln manages to avoid the temptation to romanticize the Southern Cause (or really the Civil War at all) in any way — a temptation that has proven remarkably powerful for previous generations of filmmakers. But there are valid criticisms, and Ta-Nehisi Coates has a nuanced take as usual. (Some give and take with Kushner here and here.) There’s no doubt that the movie gives us a top-down, Great (White) Man, Hollywoodized view of historical events. White House servants Elizabeth Keckley, who in real life was an activist and organizer, is portrayed as a silent sufferer and blank-faced icon of moral worthiness. Frederick Douglass, the black abolitionist who was an important influence on Lincoln, is completely absent from the movie. And Lincoln himself is allowed to exhibit personal flaws and impatience when dealing with his wife, but is portrayed as a resolute believer in racial equality. He may have been, late in his life, but it was quite the journey to get there; there are many statements by Lincoln in the record of his complete rejection of fundamental equality, and he long believed that blacks should be moved back to a colony in Africa.

He evolved from those views, as far as anyone can tell when trying to understand the true feelings of someone who was admittedly a brilliant politician. But evolution is interesting, and in Lincoln we don’t see any from the main character. Maybe as a country we’re ready to see the secession of the South in unromantic terms, but we’re not quite prepared to view the Northern heroes with all their human flaws.

I’ve always liked David Strathairn and even learned how to pronounce his name. He was very good in The Sopranos and is (or was?) excellent in Alphas. For his performance as much as anyone else’s, Lincoln is on my must-see list.

Hi Sean, Congratulations on the new website. I agree, LINCOLN is a superb piece of cinema. The annoying hiccups that Stahr flags are all there. Especially referring to the bill as the “Thirteenth Amendment.”I missed the Spader line that you mentioned, about Lincoln’s portrait on a fifty cent piece, but that story is a little complicated. Lincoln’s portrait did appear on the $10 “Greenbacks” the Union started to issue in 1861 and on a paper fifty cent note the Union began to issue in 1863–the latter so called Fractional Currency to replace the silver coins that had disappeared from circulation. But–there were five separate issues of fractional notes with different designs, and I don’t believe Lincoln portrait showed until the fourth series beginning in 1869. So the problem remains. It’s just very hard to get all the details right even when you have consultants galore.

I haven’t seen Lincoln yet, but I’m not one who believes we have to go to war to solve every problem we come across, I can’t believe that Lincoln couldn’t have found a solution to states rights and slavery in a more peaceful course of action. It seems from the American Revolutionary war to the present it has been one war after another, and I’m not saying that the film is not a great piece of art. The loss of life of all wars is simply staggering, what a waste of humanity.

There’s no doubt Lincoln evolved on many fronts, but on slavery the Lincoln historian David Donald says that Lincoln was naturally anti-slavery and he quotes Lincoln’s remark (in 1864): “I cannot remember when I did not so think, and feel.” Lincoln’s parents belonged to the Separate Baptist church who were opposed to slavery, so Lincoln grew up with such teachings. (See chapter 1, David Donald’s book “Lincoln”, Simon-Schuster, 1995.) As to how slavery factored into Lincoln’s politics (and it certainly did because of the South), that’s more complicated.

Masur, upon whom Coates relies, could not correctly describe the first scene in Lincoln: A violent hand to hand combat between rebel and African American soldiers. Nor could Masur see the southern peace commissioners’ confrontation with the African American soldiers. Masur cannot reduce Keckley’s simple invocation of her son’s sacrifice as an appeal to pity instead of a claim to justice without special pleading for an agenda. I note that Masur was most uncomfortable with the bedroom scene between S. Epatha Merkerson and Tommy Lee Jones.

I suppose it was Masur’s misleading remarks that led Coates to somehow misread Lincoln’s remarks to Keckley as portraying a firm commitment to racial equality. I can see feeling this scene is misleading for those who aren’t aware of Lincoln’s previous fetish for colonization, but the movie just doesn’t show Lincoln as committed to full equality as Stevens was.

However, Coates review does actually touch upon strongly the real historical issue in Lincoln, which is its treatment of the Radical positions. It is no accident that Stevens is left mute by both Lincolns’ attacks. Nor is it an accident that the movie doesn’t follow up on Stevens’ announcement of his program. The truth of course is that we have a powerful hint of how Lincoln’s ingrained legalism and caution might play out in his treatment of the New York City “draft riots.” That racist pogrom was a precursor of the Klan’s assault on the freedmen. There is a double irony here. The obvious one, that Daniel Day-Lewis played the lead in Gangs of New York, which grossly falsified the riots. The second of course is the double standard for historical accuracy for Gangs of New York versus Lincoln.

Pingback: Shtetl-Optimized » Blog Archive » Lincoln Blogs