A large economy is one of the best examples we have of complex dynamics. There are multiple components arranged in complicated overlapping hierarchies, out-of-equilibrium dynamics, nonlinear coupling and feedback between different levels, and ubiquitous unpredictable and chaotic behavior. Nevertheless, many economic models are based on relatively simple equilibrium principles. Doyne Farmer is among a group who think that economists need to start taking the tools of complexity theory seriously, as he argues in his recent book Making Sense of Chaos: A Better Economics for a Better World.

Support Mindscape on Patreon.

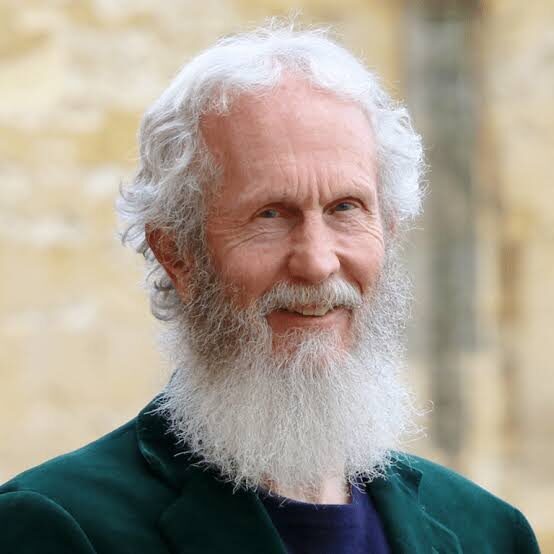

J. Doyne Farmer received his Ph.D. in physics from the University of California, Santa Cruz. He is currently Director of the Complexity Economics program and Baillie Gifford Professor of Complex Systems Science at the University of Oxford, External Professor at the Santa Fe Institute, and Chief Scientist at Macrocosm. He was the founder of the Complex Systems Group in the Theoretical Division at Los Alamos National Laboratory, and co-founder of The Prediction Company.

0:00:00.1 Sean Carroll: Hello everyone and welcome to the Mindscape Podcast. I'm your host Sean Carroll. Usually in these intros to the episodes I will start with some big picture kind of question, narrow it down a little bit, and then eventually introduce the speaker who we're going to talk to during the course of the episode. It's ideas first and speaker second. And the episode that we have here today is also that, but let me do the intro in the opposite direction because we have a very special speaker here today, Doyne Farmer. His name is pronounced Dowen. He says it's like the name Owen, but with a D in front of it, even though it's spelled like D-O-Y-N-E. Apparently some amalgamation of Irish and Southeastern US pronunciations. But he came to fame in some sense back in the 1980s when a book was written called The Eudaemonic Pie. Those of you who are of a certain age will remember this book. It was about something that Doyne and his friends from graduate school pulled off in the 1970s to win in Vegas.

0:01:05.6 SC: You've all heard of different stories of people trying to beat the house, beat the casinos in Las Vegas, either through counting cards or through high-tech apparatuses. And Doyne and his friends, they were first. They did it first, at least the first in the high-tech world. Doyne himself programmed what we would now call a wearable digital computer, arguably the first of its kind, that fit into a shoe so that you couldn't see it. And they were not counting cards or anything like that. They were playing roulette. They were using a little bit of physics. And if you're a roulette player, you know that the roulette croupier throws the ball around the roulette wheel and it spins several times. It spends some time spinning. So you could actually, in principle, time how fast that ball is moving and time the motion of the wheel, and at least probabilistically, even though you wouldn't get it exactly right every time, have a better than average chance of, or better than typical chance, I should say, of getting the right answer to where the ball was gonna fall.

0:02:11.4 SC: And they figured out that through their mechanism, they could get a substantial increase in the odds of winning. And in fact, they did win. The winnings were not very large. I have to confess to that. Hardware problems, software problems kept coming in the way, and at some point they got worried that the casinos were gonna throw them in a dark alley and beat them up or something like that. But the proof of principle was there, and it launched Doyne on a career. He went back to grad school in physics, actually, started thinking about chaos theory. It was sort of straightforward Newtonian mechanics for the roulette wheel, but chaos theory was the new thing. At the time, he was a founding member of the Chaos and Dynamical Systems Collective, which helped really put the physics of chaos theory on a firm footing.

0:03:00.9 SC: And he then became more and more interested in thinking about how to apply insights from chaos theory to predicting, to predicting the future, because the world is a messy place and there's all sorts of chaotic, complex things going on. He founded a company to play the financial markets and did very, very well at that. Better than average, let's put it that way once again. Of course, it almost is inevitable that he became involved with the Santa Fe Institute and the sciences of complexity. And given his previous interest, the particular kind of complexity that Doyne became interested in is complexity economics. So now we finally get to the topic of today's podcast. Doyne has a new book. Coming out called Making Sense of Chaos, A Better Economics for a Better World.

0:03:46.9 SC: And he's arguing, as we've talked to other speakers about, that thinking like a complex systems scientist is just so much more suited to thinking about the economy than traditional economic models. And I've talked to a bunch of economists, a bunch of complexity theorists before. I think that after this conversation, I have a much better understanding of why the that statement is true, of why thinking like a complex systems scientist is very, very helpful in understanding the economy in particular. And this is not just ivory tower theorizing. The British government asked Doyne and his collaborators and his group at Oxford University to help understand what the economic impact of the COVID pandemic would be. And they did their little complexity theory models. And again, it worked worked really well, especially compared to traditional models. So as in many ways in the world of complex systems science, I think that we're on the cusp of really getting better at this.

0:04:51.6 SC: I think that we have breakthroughs right ahead of us. This is revolutionary science. This is the middle of a paradigm shift where all sorts of problems in the world are going to have light shed on them by thinking about not just the specific phenomenon under consideration, but more broadly as a complex systems thinker. And I think that this conversation with Doyne Farmer helps convince us that that's what's gonna be happening. So let's go.

[music]

0:05:34.8 SC: Doyne Farmer, welcome to the Mindscape podcast.

0:05:36.2 Doyne Farmer: Welcome. I'm very happy to be here.

0:05:39.1 SC: So you're writing about complexity economics in your latest book. I will encourage all the readers, all the listeners rather, to go back and check out all of your previous adventures, which are colorful and fun. But today we're gonna think about you complexity economics, which leads me to ask, is there simplicity economics? Isn't all of economics pretty complex right off the bat?

0:06:01.2 DF: Yeah. Well, I sometimes worry it's not the best term. The term is there to indicate that it's coming from the science of complex systems and that we're using methods and maybe even a scientific philosophy of epistemology that's coming out of complex systems, which... Although economists like to point to Adam Smith and so on, it's very different than the way they do things. And I think it's much more explicitly complex systems than the way they do things.

0:06:37.7 SC: Great. So, of course, there is a lot of complexity out there. I mean, maybe let's ask the question this way. Can conventional non-complexity economics get anywhere by oversimplifying things? So are you, in other words, adding to something that we already know by taking the complexity seriously?

0:06:55.3 DF: Well, yes and no. That is, first of all, I'm bending over backwards to be nice to the economists. I hope they appreciate that. And so I intentionally took as much criticism of economics as I possibly could out of the book. I had several editors help me do that. Now, I think there are some things that conventional economics is pretty good at. In a simple situation where you need to understand strategic interaction, and that plays an important role, or strategic thinking plays a role, but in a simple context where you can understand, then I think it can work pretty well. I think where it fails is when things get more complicated. When you need to put in more institutional structure, or when individual agents can't reason well about what's going on.

0:08:00.9 DF: And so you really have to fall back to heuristics and more simple reasoning. And maybe to amplify a little bit on that first point, because I think it's a central one. And in my book I quote economists laying the problem out. And the problem is, and maybe we need to digress to how mainstream economics works and what the difference between the two approaches are. And then I think this will become more apparent. But in mainstream economics, in the capsule version, is that you begin by assigning all the agents, all the decision makers' utility functions, scorecards that say what they like better and what they don't like as much. And then you give them some way of reasoning about the world. Traditionally, that's rational expectations, meaning they're like Mr. Spock in Star Trek.

0:08:58.2 DF: They can reason about everything and they're very logical and they can process all the information and arrive at the correct conclusions. And so you give them those things and then you, and you furthermore assume equilibrium. Which in a standard economic model means supply equals demand. But sometimes you're in a strategic setting where it means you're doing something like game theory, where it's a strategic equilibrium, meaning we've all arrived at strategies that make decisions that are as good as we can do, given that everybody else is not changing what they're doing. And everybody does that. So that'd be the standard thing, rational expectations. Now... And then just to finish, you write all that down in equations. You solve what economists call the first order conditions, meaning you set the derivative to zero.

0:09:57.5 DF: And you compute the decisions that maximize utility for all the agents. And then you calculate the economic consequences of those decisions. Now... So in complexity economics, we do things completely differently. So it's really throwing out stuff that's been in economics since the 19th century. And we say, well, let's assume we have some agents. Let's give them some ways of making decisions that could be very simple or more complicated. But we're not assuming optimality. So information flows in. The agents use their rules to make decisions, which might be learning algorithms or they might just be simple heuristics like buy undervalued assets or imitate the best. Look around and see who's doing the best. Imitate them. Or it might be trial and error. Try something if it works, keep doing it doesn't work, try something else.

0:11:03.0 DF: Simple stuff. And so they make their decisions. We then calculate the economic consequences of the decisions. That generates new information. In addition, new information may flow in from the outside, and then we repeat the process, and we just go around and around that loop. Now, we may arrive at an equilibrium where supply equals demand or agents' decisions get locked in. If so, that's what we would regard as complex system scientists as an emergent property.

0:11:37.2 SC: Yeah.

0:11:38.3 DF: Or we might not. And actually, oftentimes, we don't. And I think that's one of the important strengths of this formalism that we more naturally capture dynamics and endogenous dynamics that is dynamics that arises from within things like business cycles where if you take say the financial crisis of 2008, the so-called great financial crisis, I think it's pretty clear it's an endogenous crisis. It wasn't like a meteor hit the earth and that caused the crisis or that people suddenly changed it was that we introduced new types of financial instruments, mortgage-backed securities, housing market got overpriced, it crashed. All these things happened from within the economy. In a mainstream model you can't get that to happen. And so you just don't get, it's very, you can get endogenous dynamics but you have to push the economy into extreme, you have to make what seem like unreasonable assumptions in order to get there.

0:12:48.1 DF: There's actually something called a turnpike theorem that says things are just gonna settle into a fixed point unless certain conditions are satisfied, like very myopic reasoning, et cetera. But if under normal, reasonable conditions it's like a turnpike. You look down the road, you see where things are going, you make corrections as needed 'cause you can see everything well ahead. And so you're not steering wildly. Now in the book, I make the, well, I show several examples where behavioral errors, bounded rationality, making mistakes we should expect people should make, lead to endogenous dynamics. And the analogy I make is that the economy is more like a drunk driver on a mountain road swerving and not quite always doing what he or she is supposed to do. So maybe one more thing.

0:13:48.1 SC: Sure.

0:13:50.4 DF: So it gets me back to what it was, what caused the whole digression. The part that economists, I think, will all agree on is when you're computing optimal strategies for each agent. You're deducing those strategies. You can't make things very complicated. Once the system gets nonlinear, once you have more than a dozen agents, you can't solve the equations anymore. And so you have to keep the model simple. You're just forced to do that. You're also writing down equations. You have to write down everything in equations. In an agent-based model, those constraints don't exist. We have models, we've run simulations with millions of agents making decisions. And so, and there's just a lot more room to put in institutional structure, heterogeneity, real world stuff.

0:14:42.0 SC: I'm sure that most audience members have figured this out, but so exogenous is some influence coming in from outside, endogenous is the dynamics within the system.

0:14:54.7 DF: Yes, thank you. Definitely.

0:14:56.6 SC: Yeah. And you're saying that classical economic theory, if you restrict yourself to the endogenous influences, because it's looking for equilibrium points, nothing should ever change with time. I mean, it can deal maybe with exogenous things, the meteor hitting, but it predicts pretty strongly that things settle down. Is that right? Is that an exaggeration?

0:15:18.4 DF: Let me just put an asterisk by this. There are special cases where you get dynamics, but they're really special cases. If you look at the workhorse models used by the Federal Reserve or any of the people who are actually using models to make decisions about the economy, they're still actually using rational expectations. And those models settle into fixed points absent external stimuli.

0:15:43.1 SC: But there are business cycle theories, no?

0:15:44.9 DF: Yeah. Yes and no.

0:15:49.0 SC: Okay.

0:15:49.3 DF: They even have names like real business cycles. But when you look at them, they don't make business cycles unless they're getting kicked.

0:15:57.0 SC: Ah, okay.

0:15:57.6 DF: So I find the name a misnomer.

0:16:00.2 SC: Got it.

0:16:01.5 DF: They're not endogenous business cycles. They're...

0:16:06.4 SC: Ah, okay. Okay. That's very interesting. I mean, it's fascinating to me. We talked on the podcast about complexity and complexity economics before. The centrality of departures from equilibrium hadn't quite sunk into me before. And it reminds me of things going on in physics over the past 20 years, because of course, we have statistical mechanics and thermodynamics, and all the classical theory is about equilibria. And you settle down fairly quickly. There have been some attempts to do non-equilibrium stat mech, but it's really only in the past couple decades that people have taken those dynamical processes. Seriously and talked about fluctuations and unlikely events and fact tails and things like that. And so could I think of it as adding time scales into the problem? I mean, maybe I reach equilibrium, but maybe it just takes me a long time.

0:17:01.9 DF: Yeah. Well, that's one of the things. But unlike in physics, where the work you're talking about builds out of the classical work.

0:17:10.8 SC: Yeah.

0:17:12.0 DF: The methods used are similar to those used in traditional equilibrium statistical mechanics. Here, we throw the whole thing out and start over. And that's actually the source of the tension within the academic community and why this kind of... This way of doing things is so strongly opposed by the mainstream academic economists.

0:17:36.4 SC: This is very helpful to me because the 2008 financial crisis is obviously something that many economists have talked about to death. And I could never quite decide whether the, everyone agrees that people did a bad job of predicting it, anticipating it even. But it was unclear whether or not it was the specific models being used were inadequate or the whole approach was inadequate. And you seem to be coming down on the very approach was inadequate.

0:18:01.3 DF: Yeah. Again, I'm trying to be nice to the economists. They were doing the best they could. But, yeah, I think there were two key things that happened. One is, I think the 2008 crisis was substantially a non-equilibrium event. Things got out of whack. We weren't sitting at the equilibrium we'd been at. Why? Because we were dealing with financial instruments we didn't properly understand. And they had side effects that we really didn't understand. When there were a few people like Robert Shiller who anticipated the housing bubble, that the housing bubble would pop, but almost nobody anticipated was how enormous the side effects on the real economy would be. And that was because mortgage-backed securities, almost everybody globally was holding them.

0:18:56.7 DF: Foreign institutions were holding US mortgage-backed securities because they were the hot new thing, great investment, low risk, high return, hooray, hooray. But what they didn't realize is when the housing bubble popped, that meant that all those mortgage-backed securities got enormously, their valuations dropped very low, which meant that all these financial institutions holding them were stressed, which meant that they were not in shape to lend money anymore, which meant nobody was lending money to the businesses in the real economy that needed it to construct new buildings and do all the things that we do in the real economy. And the real economy got whacked really hard. So I would argue it was all an out of equilibrium event, endogenously driven.

0:19:51.0 SC: One thing that I noticed... I think I saw this table in your book. If you look at the historical dates when, let's say, the stock market changed by a relatively large fraction, one thing I can't help but notice is they're almost all downward. It's not an equal distribution of fluctuations upward and downward. Is that something that makes sense to you?

0:20:13.2 DF: Oh, that totally makes sense. It's true. As a physicist, you will appreciate it because it says that the economy doesn't seem to be time reversible. If I look at time series, just from looking at the time series, I can tell which way time is flowing. Now, of course, the other significant thing that happens is the economy tends to grow. It's not that it can't shrink, but the US economy has been going up at 2% per year on average most of the time since the Revolutionary War. So that's another time asymmetry.

0:20:48.2 DF: But, yeah, markets go down easier than they go up.

0:20:56.1 SC: Is there a simple... I mean, I can guess at a sort of physics-y phase transition kind of thing. Like, the economy generally grows, but as it grows, it's also exploring new configurations and suddenly it finds a lower energy minimal and it sort of crashes down and then starts growing again.

0:21:15.5 DF: Right. Since we're talking about the endogenous-exogenous distinction, I should say disequilibrium models are also really useful when the shocks come from outside. And the good example of that would be COVID. Now, that was clearly outside. I mean, from the point of view of the economy, having a virus suddenly cause people to not go to work is an outside shock.

0:21:43.7 DF: But that was a very sharp and sudden outside shock. And we built a model in a crash program as the pandemic was starting and actually used it to advise the British government about the economic consequences of different forms of lockdowns. And that model was very, very explicitly disequilibrium, I mean, it works in a very simple way. We said, an industry can't make its product if there's no demand for the product, if it doesn't have the inputs it needs for the product, and if it doesn't have the labor it needs. And so just using that basic observation, the longer story for how we managed to guess how big the shocks were going to be and which industries would get shocked, that had to do with our knowledge of occupational labor and beautiful data set put together by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

0:22:45.6 DF: But that contained information like how close together do people work in different occupations. So from that, we can infer who would be able to go to work and who wouldn't. But we initialized the model in the steady state it was in before the pandemic started, and then we hit it with the shocks. And using the rule I said, we could see those shocks reverberating around the economy because every day we'd update the model. We'd say, oh, does this industry have labor? Does it have inputs? Does it have demand? And if it didn't have some of those, we would reduce its output. So it was a very dynamic output that changed through time. For example, some of the industries were running out of inputs a month or two after the lockdown started. So the consequences weren't necessarily felt immediately.

0:23:37.6 DF: And then once they reduced production, if they were upstream in the economy, meaning like producing natural resources or stuff that lots of other industries use, then that would propagate, as they say, downstream and hit the other industries. So there were complicated dynamic effects. And mainstream models don't work that way. They assume equilibrium from the get-go. And so I think their hands were in a straitjacket because it was a very explicitly disequilibrium events. And by the way, note that the two big events that we just happened in recent history, they're both disequilibrium events.

0:24:26.5 SC: Very, very much. And it does make me think that this is a good connection between complexity and chaos, which are two different things, but they're related to each other. Part of the spiel in chaos theory is that small deviations get you very different futures. And that does seem to be related to this inability for things to settle down, but I can't quite put it together in my head.

0:24:55.3 DF: Well, I would say chaos has two things. One is sensitive dependence on initial conditions, which is what you just said, things that are maybe so close together in the state space that you can't distinguish them, and therefore could correspond to the same measurement, could eventually become very far apart. So that's the sensitive dependence part. But the other part is endogenous motion. Chaos is really... You can get endogenous motion two ways in dynamical systems, which is what I did before I started doing economics. And one is through oscillations, which don't need to be chaotic. But there's even a theorem that says once you have more than two frequencies oscillating, you almost always get chaos.

0:25:43.7 DF: And so that says that if you're looking at an endogenous motion, and it's not periodic or quasi-periodic with two periods, then it's got to be chaos. And that has not been absorbed by the economics community. And I think it's essential because basically, if you want to have irregular business cycles that are endogenous, they must be chaotic. There's no other way to do it.

0:26:16.9 SC: Well, I guess, yeah, that's what I'm striving to understand this a little bit better. I mean, part of me wants to say, okay, let's back up. The thing you just said about two frequencies or two periods, that makes perfect sense to me. If we have a double pendulum right, if we have one pendulum hanging off another one, that is a paradigmatic example of a chaotic system, hard to predict. But if I have a little bit of friction, the double pendulum will eventually settle down into an equilibrium.

0:26:48.7 SC: And part of me wants to think that the economy, if it didn't have any outside shocks, would have a little bit of friction and settle down. But you're telling me different, and I'm trying to understand how that goes.

0:27:01.9 DF: Yeah. Well, imagine we didn't have shocks somehow. We just live in a smooth world where we're not getting hit by surprises. Now, first of all, that doesn't mean we're not going to grow. That's another endogenous phenomenon. And it's also worth noting that the economy is full of feedbacks. That's one of Keynes ' brilliant insights is that it requires demand to produce stuff. And if we have a situation where demand falls, for example, because people become unemployed, then we automatically are going to produce less, which means more people are going to become unemployed, which means we're going to have less demand.

0:27:52.3 DF: So there are feedback loops like that in the economy. And we do things to try and control those feedback loops. The reason we have central banks is to do things like control interest rates and set the rules up, adjust rules as we need to keep the economy on a steady path. But if we do that imperfectly, then we might expect oscillations. It's back to my point about the drug drunk driver on the windy road. Or in live lectures, I like to illustrate pole balancing. If you take a pole, it's got to be about longer than three feet. You put it in your hand, and you try and preserve the pole vertical, maintain the pole as vertical as possible. Well, you can keep it more or less vertical, but it oscillates around vertical.

0:28:51.4 DF: Now, think of the pole as the economy. And think of my hand as the central bank, or all the planners that are making economic decisions all the time, trying to anticipate what the economy is going to do I decided to start a business, I decided to borrow money, lend money, all those things are like my hand, trying to steer that pole. Now, and having a pole be perfectly vertical is keeping the economy on the nice steady path. So it deviates from vertical, I move my hand to correct, I tend to over or under correct, the pole then comes back toward the center, but I miss it as I come back, and so the pole endogenously wobbles back and forth. Now, to illustrate the difference in viewpoint, if again, that pole is the economy, in a standard model, the story goes like this, I am a perfect pole balancer.

0:29:49.8 DF: So somebody knocks the pole, all right, so the pole gets knocked, I then calculate exactly how to move my hand to bring the pole smoothly to rest back at the top, maximizing consumption in the economy as I do it. And before I get to the top, somebody knocks the pole again. Now, there can be elements of both stories. If I'm standing on a sailboat in a storm, I'm getting knocked all the time, that happens. But the point is, even if I'm standing on level ground, the poles oscillating, and there's no breezes, there's no outside influences, it doesn't take outside influences. So that's the side of the story that's missing, whereas mainstream tries to explain everything in the way I said.

0:30:39.0 SC: So, of course, that pole by itself is not in equilibrium it's at an unstable equilibrium.

0:30:46.5 DF: That's right.

0:30:47.6 SC: So is that, I mean, that would change my mind about a lot of things. If you're arguing that the equilibria discovered by classical economics are secretly unstable and small perturbations would tend to grow.

0:31:00.5 DF: Well, the economists know that. They are secretly unstable. But you have to assume, like with a rational decision maker, the rational decision maker can keep it pinned at a stable point. And in their favor, taking their side of viewing things, they would say, well, maybe it's a good enough approximation to say it's an equilibrium. It's true, for some purposes, just saying the poles vertical is good enough if it's oscillating through a 10 degree angle, 10 degrees it's not a big deviation. But on the other hand, I would argue that, yeah, the economy tends to go up, but business cycles or the swerves around it. And that's the pole deviating from equilibrium.

0:31:47.6 SC: Yeah, no, that's extraordinarily helpful. So basically, rather than the naive picture I had in mind where there is an equilibrium and there's dissipation and you settle into it, there's an unstable equilibrium and things around us are gradually changing. Like you said, the economy is growing. We discover new things, new resources or technologies or whatever.

0:32:07.0 SC: So, of course, there's constant jiggles at the unstable equilibrium and there's nonlinear feedback and they will want to grow unless we correct. And that correction is going to be kind of a back and forth process that is intrinsically dynamic.

0:32:22.3 DF: Yeah, exactly right.

0:32:22.8 SC: Okay, good. I understand a lot better now. So let's try to figure out what we should be doing instead of those benighted ordinary economists. I mean, how does the statement of bounded rationality play into this? I mean, clearly, it's a statement that the assumption of perfect rationality is too strong, but then how can you implement that in your better way of thinking?

0:32:46.8 DF: Well, going back to what I described before is called an agent-based model. Agent-based models are just simulations on computers that involve agents who make decisions. And the challenging part is you have to figure out how those agents are making decisions. What decisions are they making in each situation? Now, first of all, take the example of the COVID model I made. That model actually has no agents making decisions, because all we have to understand is the industry can't produce if it doesn't have demand, labor or the inputs it needs. So the production function, as it's called, the recipe for making stuff, does all the work. And the dynamics of the simulation, which tracks what everything's doing. Now, you often do need agents making decisions.

0:33:41.8 DF: That model, by the way, it worked. It was very simple and it didn't have prices. But that meant we couldn't address things like inflation. Now, we correctly guessed, we said, we think that's okay, because for the first year or so, we don't think there's going to be inflation. We actually explicitly said after that, all bets are off, and we're worried about it. So now you want to bring inflation and you've got to have agents making decisions because they're looking ahead going, oh, are we going to have inflation? What's happening? What are interest rates doing? They have to be thinking about all that stuff. But as I said, in an agent-based model, we kind of come at it from the other end. We usually start simple.

0:34:23.6 DF: I have models where the agents actually just flip coins to make decisions. So they're literally zero intelligence agents. Those models can be quite useful. They have made useful predictions. For example, if you want to predict how the bid-ask spread in a financial market, that is the difference between the buying and selling price, how does that depend on the way orders are flowing into the market? You can calculate it with a zero intelligence model. The orders flowing in could be sand grains coming in at random. But you quickly realize, oh, no, we need to refine it.

0:35:06.3 DF: So you now need to make something a little more realistic, like value investors buy undervalued assets. So several different agent-based models where the rule is this guy's the value investor or investors, and what do they do? They have some way of valuing the asset. When the valuation is under the price, they buy it and hold it. When it's over, they sell it. So simple rules like that. I have other models where back to business cycles and poll balancing, we assume a network of agents who are really, really dumb.

0:35:46.2 DF: All they do is look at their neighbors to see what their neighbors are doing. And the neighbor that's consuming the most in that period, so myopic-ly consuming the most, they go, I'll adopt that savings rate. So they all have different savings rates. They're all adopting different savings rates. And by the way, back to the instability in the economy, if you save too much, the economy doesn't work. You've got to strike the right balance, because again, to sell stuff, you've got to have consumers to buy the stuff. And those consumers then have jobs doing something that allows them to sell stuff.

0:36:25.8 DF: So you're going around that loop all the time. The balance is somewhere in the middle. So amazingly, as long as these agents don't update their strategies too often, the economy actually spontaneously starts oscillating, because agents are changing their savings rates dynamically. But also almost to me, almost more amazingly, they get pretty darn close to the optimal savings rate, even though they're absolute dummies. And selections doing all the work, you see, because you're selecting toward the agent that consumes the most, they're chasing that agent.

0:37:07.5 DF: Now that agent might be on a spending spree and about to go bust. So it's not perfect, but they get within a few percent of the optimal strategy. So anyway, a bit of a tangent, but just to illustrate the kinds of things we do to have the agents make their decisions. And then the key point is that not only do we think that can be more realistic in many settings, it can capture dynamics more naturally, because you can see the deviations from the imperfections of the economy. But it's tractable. So we can run simulations with millions of agents instead of being stuck with just a few.

0:37:48.6 SC: Right. And so just to clarify again, to the audience members who've never made a model of anything of this sort, the difference would be in a standard economic model, you would have things like supply and demand and inflation rate or whatever. And here you have individual variables in your computer simulation, representing the states and aspirations of a million different agents.

0:38:19.3 DF: That's right. But let me emphasize, we also have supply and demand and inflation.

0:38:23.9 SC: Okay, sure.

0:38:25.7 DF: 'cause those agents make supply and demand happen. And if that's in the oscillations we're seeing, there may be oscillations where there's more supply than demand or more demand than supply. And In some markets, saying supply equals demand is not a bad approximation over a sufficiently long timescale. In other markets, like housing markets, supply and demand can be wildly out of balance. It goes back to the way prices get formed in housing markets. If you bought a house, what do you do? You go find a comparable house. You go to a real estate agent who says, "Here are some comparable houses." You would just tweak it up or down a little bit. You try to sell your house at that price. If it doesn't sell, you mark it down. If it doesn't sell again after a month or two, you mark it down again. Maybe at the end, you go, "I don't want to sell my house, this is too cheap," and you pull it off the market. So in housing markets, you can see supply and demand imbalances that are more than an order of magnitude. You can see that you go through the housing crisis, we flipped from a market where there was a huge excess of demand to a market where there was a huge excess of supply, and prices are responding very sluggishly to that. Those much more... And you can't capture that in a mainstream model 'cause you can't write it down in an equation simply.

0:39:48.2 SC: Well, in the mainstream models, I guess they have no individuals in them if I understand correctly, the role of the individual is just to be absorbed into the collective notion of supply and demand.

0:40:00.6 DF: Yeah. So let me be a little more precise there. In macro, that's more or less true, though these days, a hot topic in macro is having heterogeneous agent models, where you have things a Gaussian distribution of agents... Just one-dimensional Gaussian with some agents having more earning power than others.

0:40:24.4 SC: Okay.

0:40:25.3 DF: So they're putting that in. But in our models, what do we do? We create a synthetic population with a million agents, where we try and match all the demographics. Earning power, education, age, even race and gender. And sow match all those characteristics of the population We can even do it regionally, so it may vary. So We have the power 'cause we can have millions of agents to really make all this much more, much richer and much more accurate.

0:41:03.6 SC: And one of the advantages of this approach, as I understand it from your book, is that the agents in your model can take on specializations in a certain way. I mean, you use the analogy that the economy is kind of a metabolism, the metabolism of civilization.

0:41:19.6 DF: Yeah. So, mixing together a couple of metaphors there, but in a good way. What does the economy do for us? First of all, when I wrote my book, I realized it made me appreciate the economy more 'cause I really tried to reflect on what is this thing doing for us. I would argue it's the digestive system of civilization... The metabolism. It takes in, just our metabolism, what does it do? We take in food, from the outside world, we reform that food, we break it into pieces, and we make it into something else. What does the economy do? It takes in natural resources and then combines them with labor. And we reform it into goods and services that we consume, or that other industries consume. So it's the engine at the bottom. It's having the economy work is like having a square meal every day and having that energy allow you to walk around and do the tasks you need to do. Very fundamental to everything we do.

0:42:42.9 DF: And now, the ecology analogy comes from the fact that ecology is really a theory about specialists. I mean what is grass? Grass is an organism that takes sun and earth and water and makes grass with it. A zebra is an organism that turns grass into zebras. A lion is an organism that turns zebras into lions. They're all specialized. But the interactions can be rather long-range, get rid of the lions, grass gets hammered. Even though the lion might not interact with the grass except to roll around in it occasionally, because the lions are controlling the zebras, and the zebras are controlling the grass. It's all connected.

0:43:32.8 DF: So Economists sort of I mean Adam Smith already said something that. But our models very explicitly do that in a bounded rational setting. 'Cause Why are we specializing? We're specializing 'cause we're only boundedly rational. We get good at doing very specific things. We can't do everything. And so we put that in from the start. Our models, 'cause we can put in more institutional structure and so on, allow us to think about the ecological part of the story with more richness. Now back to the metabolism part of the story. The metabolism it's a bit different from your body and metabolism is maintained by an ecology that the metabolism is feeding. Metabolism feeds all of us, but we're making that happen by each of our specialized roles. We're like the little cells inside your digestive system that are themselves being fed by the fact that we're digesting food, but those cells can be very specialized and doing very different things.

0:44:43.8 SC: And you even have some prediction that turned out correctly about how different industries that were able to specialize more would find efficiencies and lower prices.

0:44:54.9 DF: Yeah, so we were inspired by ecology. One of the nice things about hanging out at SFI is you get to know a little about a lot of things. And we said, well, the same basic thing is going on in the economy 'cause we have all these specialists. And in particular, in ecology, one of the central ideas is that of a trophic level. With the grass, grass has a trophic level of one, zebras have a trophic level of two, lions have a trophic level of three. The way you compute trophic levels is you say, an organism is equal to one plus the average trophic level of the things it eats. Right?

0:45:39.5 SC: Yep.

0:45:40.7 DF: So you can actually just write that statement down and derive a key equation about the economy. 'Cause In this case, what happens is industries, the trophic level in industry is one plus the trophic levels of its inputs. Labor, we put as the foundation, that's trophic level zero. So an industry that purely has labor has trophic level one. It turns out this is very closely related to a concept in economics called output multiplier, which is used in a different way but defined in a similar way. Now, okay, so how does this relate? What prediction then is that the deeper your supply chain is as an industry, the faster you'll improve. Now you go, wait a minute, that sounds weird. Well, first of all, the depth of the supply chain is the trophic level here. Why? 'cause if, let's suppose you don't take in very many labor inputs and all your inputs are things that already have high trophic levels, then you're gonna have an even higher trophic level than your inputs. You keep going back down until you get back to labor. So in fact, the trophic level is the average time it takes a dollar that an industry pays to its labor to get into somebody's pocket or, in other words, to get all the way back to all the labor that went into making the thing as you go down the chain.

0:47:19.9 DF: So this allows you to compute these trophic levels for industries, which typically, as in biology, organisms eat more than one thing, their trophic levels aren't just integers, they're more complicated. Similarly, here, you can compute trophic levels for industries. Now, suppose we assume that every industry is innovating at about the same rate model assumption, but a good place to get started, we can let it be different, but let's start by assuming they all innovate at the same rate. Well, then, if you have a deep supply chain, there are many industries that innovate on the way up to your industry. So you experience the product of all those innovations coming up the supply chain.

0:48:03.7 DF: So you have my laptop, if the titanium that Apple is using is cheaper, that helps make my laptop cheaper. If the chips get cheaper, etcetera, you're inheriting all those improvements in addition to the improvements the laptop designers themselves make. So then we just compute it, this means things with deep trophic levels their product should improve faster, meaning they should get better or cheaper or some combination of the two.

0:48:36.9 DF: And sure enough, we looked at the data, and we took advantage of the fact that trophic levels change slowly through time. So you can roughly speaking, assume they stay constant. And you can predict 14 years ahead which products are gonna be cheaper or not just based on that assumption alone. The prediction's quite good. And amazingly, it gets better as you go further forward into the future. As someone who does a lot of predicting, that's pretty unusual.

0:49:06.4 SC: Well, biologists who think about evolution have long wondered about the development of complexity over the course of biological time. Why is it that organisms seem to become more complex? And one answer One possible answer is that they find new efficiencies. I guess that's kind of your doing the economic version of that.

0:49:24.3 DF: Yeah. Now, interestingly, in biology, competition is a key part of evolutionary theory. But evolutionary biologists view competition as what leads us to speciation, that's one of Darwin's key insights. Whereas in economics, the mainstream people like Milton Friedman say no, competition means you quickly come to equilibrium a state of rest. So they arrive at a completely different conclusion, both using competition. Now, it's in part 'cause economists start with rationality, they assume we're all really smart, so we figure everything out, and that gets us to this equilibrium quickly. Whereas in biology, there is random variation that's being amplified as a result of the competition and actually causes species to diverge. I would argue that's also happening in the economy. 'cause, well, in some cases, we may behave rationally. I'd say the cases where we behave rationally are the ones where things are really simple, so we can figure them out. But most of the time, it's pretty complicated, so that's not such a good approximation. We overshoot, undershoot, and differentiate.

0:50:44.9 SC: Yeah. What is the role of innovation here? Does innovation count as an endogenous happening or an exogenous one?

0:50:52.1 DF: Well, I think it's fundamentally endogenous. But it's a challenge to model. In economics and biology, you can just say, well, innovation is randomness, you randomly change a gene. Or, okay, you have to deal with recombination, which is more complicated. But it's just a process you can specify in an algorithm 'cause we have this universal biological code that everything follows. Whereas we don't have anything that clean in the economy, innovation depends on human reasoning. Sometimes just assuming it happens randomly is not a bad start. There's something called rights law, or learning by doing, it comes under several different names. That's a very useful way to predict technological improvement. The theory for that, actually, ironically, was originally started by John Muth. John Muth is a guy who actually invented rational expectations in 1960. But he also he could work with both hands. He said, let's assume that inventors just throw darts at a dartboard at random. Let's assume they're just smart enough to see when they've made a better throw. So he then showed that you got rights law, although only with this exponent of one that's the only exponent he could run.

0:52:23.9 DF: Fast forward, there was another simulation paper, and then we wrote a paper where, again, we enhanced that idea by looking at the fact that technologies are connected within a device. If you change the carburation system, you may need to change the ignition system. So we looked at what's called a design structure matrix that automobile designers and other designers of complex things use to understand interactions. We enhanced the theory to deal with that, derived a bunch of stuff, physics-style, and we were able to show that we derived the rights law exponent. And show that the more complicated and less modular the system is, the lower that exponent is, and the slower it improves. And that's been tested, it seems to be more or less true. It's another example of throwing darts at a dartboard actually being good enough to get you there, as was ironically realized by John Muth, the founder of rational expectations. But somehow economics got locked into a framework where you couldn't do what Muth did anymore. That's just bad cricket to assume that people just flip coins.

0:53:39.5 SC: I think it's often the case that if you go back to some of the classic papers in a field, they were much more thoughtful and nuanced than the sort of high-contrast version that survives into subsequent generations.

0:53:48.6 DF: Yes, I think the same is true in physics and...

0:53:52.9 SC: Absolutely.

0:53:54.5 DF: Any other discipline. 'Cause those guys had to wrestle with coming up with the concepts in the first place, so they understood the slippery ground they were standing on better than subsequent generations.

0:54:06.9 SC: Exactly. So One thing you've mentioned a few times is this idea that we now have access to giant computers. We can do agent-based modeling, we can have a million different agents. And even if the actual society we want to model has a few hundred million, surely a million is a pretty good sampling. But you sort of hinted at the idea that therefore, you get results that I couldn't derive analytically that I couldn't figure out without doing the model. That would make me sad, I'm a pencil-and-paper kind of person. How well do we know that we just haven't yet been able to derive some of these results?

0:54:45.8 DF: I think actually, the simulations will help us derive better theories. The theories that get derived, though, are different than that standard template I gave you in... Although sometimes it could be that if it goes to equilibrium could work. But the theories that we complexity economists use are often more statistical mechanics or evolutionary biology models, which may or may not have equilibrium in them. And so It's a much more flexible theoretical framework. But I'd to draw an analogy to fluid flow.

0:55:26.1 DF: The Navier-Stokes equations, you can derive them from Newton's laws. But you can write them down, they take one line that looks pretty simple. A few little upside-down triangles they're confused... But once you understand what the math means, it's simple to write down. Solving them, they're not solvable in general. We now know why, it's 'cause they have chaotic solutions. When you have chaotic solutions, there are typically no shortcuts to just grinding things out numerically one step at a time. They're intrinsically complex in that regard. But now back to theory. One of the big changes in fluid dynamics is we now have numerical fluid computation. We can make use of computer power to simulate what fluids do pretty accurately. But that's also been a big driver of theory 'cause now you can test your theory without having to set up a wind tunnel and get a big grant from the NSF. There's a rich interaction between the simulators and the equation guys. So I actually think being able to simulate is ultimately gonna give us a deeper theoretical understanding.

0:56:48.0 DF: And by the way, let me say, when we see a phenomenon in an agent-based model, the first thing we do is try and strip it down. We go, let's get at the pulse of what's causing this. So we start throwing stuff away or using really simple dummy versions for components. If it keeps on doing it, we go, okay, that's not the cause. So we try and figure out the causality by doing what biologists would call knockout experiments. Also, we often get the phenomenon by doing addition experiments, meaning we start simple, we add a feature, we look at what happens, we add another feature, we look at what happens. So you can go from either direction to try and pin down the causality. And then once you do that, the theoretician can step in and try and make a stripped-down mathematical model and, in some cases, explain what's happening.

0:57:38.6 SC: So when you say we, as in the complexity economists, I presume, I mean trying to be as fair as possible, how does that fit into the larger economics profession? I know that I'm completely biased in the economists I talk to 'cause I hang out at SFI, but at the major departments you're at Oxford, it's not exactly a small backwoods place are people respecting this new approach to economics?

0:58:11.2 DF: By and large, no. A few exceptional individuals do. My book has an endorsement by Larry Summers, who really surprised me 'cause I sent the book, the early manuscript, to him saying, "Larry, I used your name several times in the book. Just search for your name, look, and see if what I said is okay and let me know. I wanna be nice to everybody." To my astonishment, he sent it back saying, "I read your book, and I really agree. I think you have a really good point. You made some errors." He corrected a bunch of my errors, but he said, "I overall agree." So, wow, I was blown away.

0:58:48.3 DF: My old friend, John Geanakoplos, who was actually Larry Summers' roommate when they were graduate students at Harvard, he's also we've been arguing about this stuff since the late '80s. So yeah, he appreciates it. I've coauthored papers with him. My colleague, Andrew Lowe, at MIT, there are a few people like that. But by and large, what we're doing is ignored by the mainstream. We can't publish in their journals. They'll just say, "This is, you're not making the kind of theory we consider acceptable." So it's like a loop quantum gravity person trying to publish in a string theory journal, for those of you who happen to know that controversy. So yeah, there's not a lot of traction with the mainstream.

0:59:45.4 DF: Now, things are changing. I sense some cracks opening up. We're getting interest from central bankers. We now have a variation on our housing model that is used by, I would say, about six or eight central banks in Europe. There is now an agent-based macro model being used by the Bank of Canada, being developed at the Bank of Italy. So we're starting to get traction in that domain. And I've started a company called Macrocosm that is dedicated to scaling up the solutions and reducing the practice. So if a journalist calls me and says, "What's going on? And what's gonna happen with the war in Ukraine?" I just look at what the model's doing 'cause it's ingesting the inputs all the time and staying up to date. And so we're starting to see practical applications. And my theory of change is that once those practical applications get enough traction and once, as economists will say, it takes a model to beat a model, once our models start beating their models in hard empirical terms, they'll have to start paying some attention.

1:01:04.2 SC: Yeah. You have to actually have a result, have some success, then people will listen to you not just 'cause you think it's cool. That's true in any academic field.

1:01:13.0 DF: Yeah, yeah. Well, sometimes let me correct that a little bit if you think it's cool and you're within the main paradigm you can get a paper published 'cause it's cool. But if you're outside of the main paradigm, no matter how cool it is, they're not gonna pay attention to you until you have empirical results.

1:01:27.3 SC: Well, speaking of those results, I mean, it's one thing to say, "Oh yes, the 2008 crash, I could have predicted that." It makes sense to me. How quantitative can we be about the next crash? I'm a little bit worried from what you said, that it's almost inevitable that there will be one.

1:01:39.4 DF: Well, I mean, I think it is inevitable there will be one. You just look through the history of economies. They happen regularly. Before we instituted the Federal Reserve in 1913, the US on average had a financial crisis of some form about every seven years. And now since we did the Federal Reserve, they're less frequent, but the ones we've had have been doozies. We have the Great Depression and the Great Financial Crisis. We've had some whoppers. So we still don't know how to control the economy properly. And until we do, we should expect we're gonna have crashes. And it could even be that the way we're controlling it works well most of the time. But when it fails, it actually makes a bigger crash than would have happened in the old days, where we weren't really controlling much of anything other than doing weird stuff with the base metal we used where the metal we used based the currency on, which was pretty arbitrary. So, yeah, I think we are gonna have more crashes. Now, I do think that agent-based models can help guide us better, and maybe once we get good models, we can soften the intensity of those crashes or maybe even just understand how to keep them from occurring. I don't know. The jury's out, but I'm optimistic.

1:03:15.0 SC: Well, I guess for the 2008 crash, you mentioned everyone has mentioned the crucial role played by novel financial instruments. Is that something I don't know if complexity economics helps us here but is that something that we can sort of be more cognizant of the dangers of ahead of time?

1:03:37.3 DF: Yeah, definitely. One of the things I talk about in my book is what I call market ecology. The classic theory of markets that's dominated a lot of the discourse is efficient market theory. And the idea is that you can't beat the market. But also, so that's informational efficiency. There's also allocational efficiency. The allocations of effort we're making to different activities are correct. And the market's pretty informationally efficient. I managed to beat it. We managed to beat it at a prediction company by a pretty steady rate. Odds that we were just lucky monkeys are so close to zero as to be negligible. But the allocations can be quite wrong. And that's what happens in crises. So under the theory of market ecology, it's like the theory I said before about the production system in the real economy. But the way you think about it is those different species of investors, and they're all specialized. Warren Buffett does his thing. There's another guy, John Henry.

1:05:19.6 DF: He's a trend follower. He says if the market's been going up, it'll keep going up and looks at little patterns and prices to decide when to buy and sell. They're market makers. You can make a list of... I can easily write down 15 or 20 different types of strategies in financial markets. And while there's variation in how people execute those strategies, they're broadly... It's like species in biology. And so under the theory of market ecology, we need to think of the market as an ecosystem with specialized actors. They feed off of the inefficiencies in the market. They're what's making the market efficient, but they never achieve perfect efficiency. We see swings around perfect efficiency, particularly when new stuff happens. Mortgage-backed securities are only one of several examples of new financial instruments that caused bad stuff to happen in markets.

1:05:54.6 DF: And so under that theory, you can then simulate what's going on in markets and understand why markets malfunction. The efficient market theory assumes they work perfectly, so it doesn't give you any insight into why they malfunction. It's like the pole balancing inefficient market theory. It's always straight up. If you wanna understand why it deviates from straight up, you have to do something else. And I maintain that market ecology is the key. And so that then will allow us... One of the things... To back to your question. Regulators, I argue, should be simulating the market. They have all the data to understand the species and who they are and how they interact, 'cause they can see what everybody does. And so we could have a standard simulation of markets. And whenever a new financial instrument comes in, we put it in there. It's like an invasive species in ecology, and we test it out to see what its side effects are. And if we were doing that leading up to the great financial crisis, we would have seen the side effects of mortgage-backed securities used with high leverage.

1:07:06.5 SC: So you're trying to convince central banks and planners and prognosticators to take this approach proactively?

1:07:12.4 DF: Well, I'm actually trying to convince the SEC 'cause the central banks... As a central bank, you only see your part of the story. You know your positions, you don't know what everybody else is doing. But the SEC can look at anything it wants to and does whenever something goes haywire.

1:07:29.0 SC: Okay, that makes sense.

1:07:35.3 DF: So the data could just be flowing in, they could be simulating what's happening, and they could be doing counterfactual experiments. So do we need to be worried about leverage getting too high here? Crank it up. Oh, wait a minute. We've got to get people to lower their leverage.

1:07:50.2 SC: So you're investigating possible worlds in your computer?

1:07:52.8 DF: Yeah, exactly.

1:07:57.6 SC: And I should say, SEC is the Security Exchange Commission for those non-Americans listening to us. Okay, I mean, I guess maybe the last thing to ask about... One more big-picture question about complexity. One of the worries about people who are enthusiastic about complex systems, such as ourselves, is that there's no "there" there. There's the economy and there's biology, and there's the internet, and these are very different things. To what extent have your investigations into the economy actually been helped by thinking about complex systems for their own sake or analogous systems that are not economics? You've already given us some examples with biology.

1:08:40.6 DF: Yeah, well, they've certainly been helped by that. I... In my career, I've always had the problem that I never fit into any discipline. So I'm one of the most interdisciplinary people around 'cause I've straddled disciplines without being in one through my whole career. And by the way, you said, "Oh, you're at Oxford." But actually, I'm in the Department of Geography and the Environment. I'm sorry, I'm not in the economics department. They do not have...

1:08:41.0 SC: Okay, very good.

1:09:06.7 DF: And that's characteristic. There are no economics departments in the US that do complexity economics. I mean, okay, Blake LeBaron sits in an economics department at Brandeis. He's one guy. There's a few people, but I can name them on the fingers of one hand. There's a computational social science program at George Mason run by Rob Axtell, but it's not economics. And now in Europe, there are some economics departments that do this, but they're not the ones with a lot of status in the field. They're forced to publish in what are viewed as inferior journals. And so it's an outgroup. And so it's still a struggle to get jobs for students that wanna do this kind of thing. I'm approached by perceptive young students who say, "I'm not happy with what I'm getting taught or would be taught in economics. Can I work with you?" And the first thing I have to say is, "Yes, but you're not gonna get a job in the Harvard economics department when you're done."

1:10:09.1 SC: Yeah.

1:10:21.3 DF: I do have students now who are at the World Bank, at the International Monetary Fund. They're getting out there at the Bank of Spain. I have students who are now in that side of things, but there's more open-mindedness there.

1:10:40.7 SC: It's a market inefficiency. A department can leap upward by taking this stuff more seriously.

1:10:45.8 DF: Yeah.

1:10:49.7 SC: Let's hope that they do. Doyne farmer, thanks so much for being on the Mindscape podcast. This is very great.

1:10:54.0 DF: My pleasure.

[music]

Efficient market theories based on rational investors making decisions based on markets that reflect all existing information are laughably simplistic and wrong. If they were right no one could make any money in the market. Complexity theory is the only way to really understand markets, the weather and other hypercomplex systems. It is remarkable that complexity theory has not been more widely accepted and integrated into economic research and study. It should and will be.

Pingback: Sean Carroll's Mindscape Podcast: Doyne Farmer on Chaos, Crashes, and Economic Complexity - 3 Quarks Daily

As Doyne Farmer noted in the podcast, these are some of the reasons chaos theories are important in developing economic models:

o Economic systems are often nonlinear, meaning small changes in initial conditions can lead to vastly different outcomes, which can create cycles of boom and bust that are difficult to predict.

o Things like market crashes and bubbles occur. Traditional linear models fail to capture the true nature of these economic fluctuations, but chaos theory can improve predictions by accounting for complex dynamics.

o Understanding chaotic behavior helps in developing better strategies for managing economic risks and can inform more effective economic policies by recognizing the inherent uncertainty in economic systems.

Some of the challenges:

o Economic data often contains a lot of noise, making it challenging to identify chaotic patterns.

o Small sample sizes can limit the robustness of chaos test in economic data.