A common argument against free will is that human behavior is not freely chosen, but rather determined by a number of factors. So what are those factors, anyway? There’s no one better equipped to answer this question than Robert Sapolsky, a leading psychoneurobiologist who has studied human behavior from a variety of angles. In this conversation we follow the path Sapolsky sets out in his bestselling book Behave, where he examines the influences on our behavior from a variety of timescales, from the very short (signals from the amygdala) to the quite ancient (genetic factors tracing back tens of thousands of years and more). It’s a dizzying tour that helps us understand the complexity of human action.

Support Mindscape on Patreon.

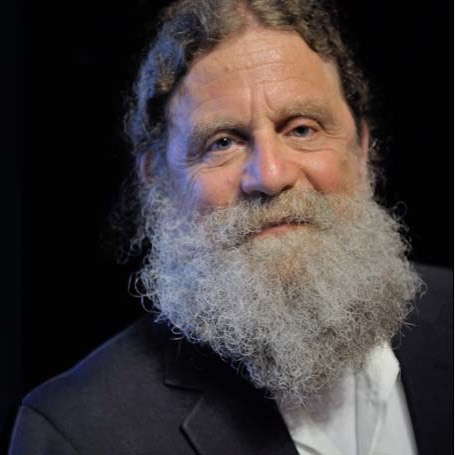

Robert Sapolsky received his Ph.D. in neuroendocrinology from Rockefeller University. He is currently the John and Cynthia Fry Gunn Professor of Biology, Neurology, and Neurosurgery at Stanford University. His awards include a MacArthur Fellowship, the McGovern Award from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and Wonderfest’s Carl Sagan Prize for Science Popularization.

- Stanford web page

- Wikipedia

- Robert Sapolsky Rocks (fan page)

- Amazon author page

- YouTube lectures on Human Behavioral Biology

- IMDb

[accordion clicktoclose=”true”][accordion-item tag=”p” state=closed title=”Click to Show Episode Transcript”]Click above to close.

0:00:00.0 Sean Carroll: Hello everyone, welcome to The Mindscape Podcast. I’m your host, Sean Carroll. And let’s say that you’re faced with a difficult decision to make, let’s say you’re wondering whether you should watch a basketball game on TV or listen to an old episode of The Mindscape Podcast. And you think about it, you weigh the different factors, you come to a decision, and then someone asks you, why did you make the decision that you made? And you would offer some explanation, some reason, “I wanted this, I value that, and I made the decision based on these calculations.” So today’s guest, Robert Sapolsky is here to tell you that you’re wrong [chuckle] no matter what you gave as explanations, almost no matter what. Maybe you’re exactly right, but more likely you have simplified things and rationalized quite a bit. Robert Sapolsky is a neuroscientist, a neuroendocrinologist, I believe is the technical term. Also studies other aspects of biology, psychology, anthropology, Primatology, and is a very well-known researcher in the field of human and broader primate behavior, the author of a book just a couple of years ago called Behave: The biology of humans at our best and worst.

0:01:09.1 SC: And the things he tackles in this book… It’s one of those books, every single reviewer refers to it as magisterial, which is a way of saying that it’s both long and good. And the topic that he tackles is, why do we behave in the ways that we do? And in particular, why do we make the decisions that lead us to behave in the ways that we do? And his thesis more or less is that there’s no one answer to that question. There’s no single thing that explains why we do is a complicated set of factors from things that are operating on time scales of less than a second to things that are operating on time scales of thousands or millions of years. And what we do is, we rationalize, we invent reasons that may have some relationship to the actual reasons that exist, but they’re not exactly the same reasons. So, what we’re gonna do in today’s podcast is talk about all of that, it will touch on common Mindscape themes like free will and plasticity of the brain and what you can do with it, and also the ability of humans to think about the future in different ways. And also we keep coming back to the question of what good this knowledge is?

0:02:20.5 SC: If you really understand what’s going on in all the different parts of your brain and your genome and your experience that go into making a decision, does that help you make better decisions in some definition of the word better? And at the end, we decide that you should buy Robert Sapolsky’s books. [chuckle] Although to be fair, that was my idea, not his to say that. I am of the opinion that knowing more about what’s really going on in our brains and our behavior helps us understand what we should do, as well as what we do do. Maybe it’ll help you, let’s see, and let’s go.

[music]

0:03:14.1 SC: Robert Sapolsky welcome to the The Mindscape Podcast.

0:03:17.2 Robert Sapolsky: Well, thanks for having me on.

0:03:18.7 SC: So you’ve written this wonderful book called Behave, studying how… Why we behave? Why we do the things we do? And I think, maybe for fun, it would be good to start rather than with the true reasons for why we behave the way we do. Surely everyone has a straw man idea in their head, right? People must think they know why we behave the way we do. So, what is the wrong idea that you’re sort of trying to fix that we all have in our minds?

0:03:46.0 RS: Well, basically that there’s any discipline, which is it, which is the holy grail, which is the code of codes that explains everything. And this comes in different flavors depending on what kinda scientist you are and what kind of consumer of science either everything in the world is explained by genes…

0:04:08.9 SC: Right.

0:04:08.9 RS: Or everything in the world is explained by brain chemistry or by hormones or by… And in all these cases, you get a very narrow interdisciplinary view as to what the behavior is about and where does it come from. And the song and dance that I just spent endless number of pages on in the book is, [chuckle] you gotta incorporate all the different influences that, who occurred before a behavior, starting what’s going on in your brain one second before up to what sort of evolutionary forces have been playing out in the last million years, because they’re all pertinent to why we do what we do.

0:04:50.7 SC: Well, it raises an interesting philosophical question, I don’t know how familiar you are with the philosophy literature that has now bled over into sort of computer science and social sciences about causality and Bayesian networks and all this stuff, but what do you mean by what causes something like this or what is the reason why? Do you personally have to worry about that question?

0:05:13.1 RS: On some level, although, rather than like Bayesian stuff absolutely terrifies me, and [chuckle] sort of everything that comes with it. And fortunately, I can figure out how to bypass at least to what actually counts as causal, because what I think the most important thing to come out of studying the biology of our behavior is not highfalutin debates about the nature of causality, it’s getting people to stop thinking that people are the causes in a conscious will-fill agent-filled way that people are responsible for their behavior.

0:05:53.1 SC: Right. Well, this is something… This is another philosophical issue that I’m sure we will get into down the road here, but the free will issue, and it’s something we’ve talked about on the podcast quite a bit. And I think hopefully none of us in the room, or at least, presumably none of us in the room here are believers in libertarian free will, and the idea that there is some spirit inside us that is not beholden to the laws of nature whatsoever, but that many of us, many of my best friends, including myself, are compatibilists about free will. We think that is a useful way to think about human agents making decisions, but you sound like… I think I get the idea from your book that you’re more on the other side, that you want to dismantle the idea that we should think of people as agents responsible for their actions.

0:06:39.9 RS: Yup, I think I have lost count as a hard incompatibilist as the label goes. You know, there’s kind of a sense that it seems self-evident from my perspective, if you spend enough decades studying enough different ways in which our brain and behavior are influenced by stuff we have no control over, that put all those pieces together, and free will is just what we call the biology that hasn’t been discovered yet.

0:07:13.3 SC: So you think that as we understand more and more about the biology, the idea of some room left for human free will will just go away?

0:07:22.9 RS: Yeah, basically, because if you look at, I don’t know, the last 500 years of knowledge, that’s been a theme over and over. And in some ways, the last half millennium what biology and behavior has mostly consisted of is people saying, “Oh, I had no idea that had something to do with why that behavior happens.” And what has occurred in the process is if there is free will, it’s getting crammed into smaller and smaller places, and if I’m trying to be a good house guest and not a jerk or whatever, I can usually leave it there and say, you know, if you want to have some free will, go for it, if you want to cite free will as to why you flossed your upper teeth this morning before your lower teeth, be happy, go for it.

0:08:13.7 RS: But in substantive ways, all that science has spent centuries doing is teaching us, oh, that’s actually a biological phenomenon, that’s actually stuff out of our control, that’s actually stuff that was sculpted by issues that were sheer histories of luck or bad luck. All we are is the sum, nothing more or less, of what our biology and its interactions with environment have been.

0:08:42.1 SC: Right. Which is the perfect segue, clearly, you’ve done this before, into talking about what the reasons are that our biology has become that way. And in the book, you have this device of sort of going backward in time, of looking at things that work on very short timescales to affect our behavior and then going further and further into the past to look at other things that affect our behavior, and I’ll confess, I was not able to do any better than that, so I figure we can just sort of rehearse that kind of explanation, and that should give us an opportunity to cover lots of interesting ground. So what is going on in the brain immediately, how should we think about our very quick reactions, our subconscious, our system one kind of behavior?

0:09:26.2 RS: Great. One of the things we’ve learned, and we could be talking about a lot of different domains of behavior here, but the two that interest me are the ones that would be labeled our best behaviors and our worst ones, because that’s this hugely challenging thing about us as a species, we are simultaneously the most miserably violent species on earth, while we are also the most cooperative and the most altruistic. And how do you balance those two? And how do you make sense of them? And especially, how do you make sense of the fact that the same exact behavior can count as wonderfully pro-social in one setting and wildly antisocial in another.

0:10:09.2 RS: Now, as we begin to look at that, like somebody does one of these behaviors, and often when we say, why did that happen? Why did that person do that just now, the first pass is we’re asking a neurobiological question, what went on in that person’s brain a second ago or a minute ago, that caused those muscles to get a command to pull that trigger or put your hand empathically on somebody else’s or whatever the behavior was. And what we now know is there’s all sorts of outposts in the brain, the usual suspects, frontal cortex, amygdala, anterior cingulate, the ventral tegmentum, insular cortex. If these are not familiar, don’t panic, they’re not relevant. But mainly there’s areas in the brain that are really central to us deciding what counts as the right thing to do.

0:11:08.8 RS: And system one versus system two, what we see over and over, is the elements that go into us making those decisions, the percentage of which… The percentage of those that we are conscious of and we believe that we were deliberating between choices that we had the option to choose is tiny; instead, we are being run by subterranean neurobiological forces in our brain. And the classic way of demonstrating that is you ask somebody to write down what their favorite detergent is. And people are more likely to say Tide if they’ve just read a paragraph about the ocean. And when you ask them why, they don’t say because I just read a paragraph about the ocean, they’re going to fabulate some supposedly rational reason why post-hoc, implicit, unconscious stuff brought them to that point.

0:12:08.7 RS: And when we look at us in our most impactful moments, people spend an awful long time thinking about moral decision-making, do we think our way to our decisions or do we feel our way. And for a long time, thinking our way was the dominant model because that seemed, oh, so much more brainy than like being some lizard going about its actions. What has become clear is an awful lot of the time, we are feeling our way to our moral decisions, and we’re coming up with justifications afterward for why that makes perfect sense, what we just did.

0:12:49.1 SC: And is there some clean distinction between those decisions that are more cognitive? I mean, when we buy a house, I’m sure there are some emotional things that come into it and some rational things that come into it. How well do we understand that?

0:13:03.8 RS: Well, it depends on what level you’re looking at. If you’re sticking somebody in a brain scanner, you could see that if they give them a decision to make about something totally like soulless and bloodless and cold or whatever, do you want to open up this can of vegetables or that can of vegetables, you’re just activating some not very exciting cortical regions. When you are now making a decision of like, do you give this person the death penalty or not for this unspeakable thing that they did, you’re now activating the cortex, but you’re also activating emotional parts of the brain’s limbic system. But the thing that is most important about that is you can tell the decision someone is going to make by looking at the read-out from their limbic emotional brain, before you get a read-out from the cortex, it’s a better predictor. That’s more likely when you’re trying to figure out if somebody is guilty or not, and this has been done with brain imaging studies with mock jurors, you’re using your cortex to decide on innocence or guilt. When you’re deciding how much to punish them, it’s all the limbic system.

0:14:17.4 SC: And so it’s both that there’s a lot of unconscious stuff going on below the surface, but also that we sort of shamelessly rationalize it into a more cognitive explanation after the fact?

0:14:31.0 RS: Exactly, and one of the best ways of spotting when that’s happening is when we’re not yet able to do the job of rationalizing, when you’ve got somebody sitting there and they say, “You know, I can’t quite put my finger on it. I can’t tell you why exactly, but when those people do that thing that’s different from what we do, it’s wrong, wrong, wrong. And in fact, it’s morally wrong, I can’t tell you why, but it’s wrong, trust me.” Like that is your like red light’s going on, saying, this is somebody who is running implicitly on non-conscious decision-making about really consequential stuff, and they haven’t gotten there yet in their cognitive rationalizations to say, a-ha, I just thought of it. This is why when they do that, it’s totally wrong because it’s going to teach our kids bad values, because it’s the same thing they did to our ancestors in the battle, whatever, in 1428, because, ah, that’s the justification I’ve just come up with for the fact that I’m making those decisions predominantly emotionally and implicitly.

0:15:40.7 SC: And there’s a couple of questions that immediately arise. One is, do we have some sort of evolutionary explanation for where all these different systems come from, do they serve good purposes?

0:15:51.0 RS: Yeah, and this is where you could easily get into a debate between the Mr. Spock types and the new age, you know, hot tub sort of folk contemplating their navels, as to like, wouldn’t it be a so much better world if all we did was make decisions based on rationality, would say the Mr. Spock types, and wouldn’t it be a so much better world if we made our decisions based on feelings and feelings for our fellow humans, say the hot tub folks. And what you see is, like big, unradical surprise, you need both. And when you get people who have damage to parts of the brain that are much more about one component or the other, you get totally different abnormalities, but you sure get abnormal behavior in both cases.

0:16:43.6 SC: I did have Paul Bloom on the podcast. He wrote this wonderful book called Against Empathy. But I took the other side, and I take it that his idea was that if you put too much emphasis on empathy, you’re sort of intentionally, or at least consciously, giving rein to those more emotional systems underground rather than the cognitive rational part of your brain and therefore, we should sort of give more emphasis to the rational part of our deliberation rather than our empathy. Where do you come down on that?

0:17:18.9 RS: Well, I think his stuff is wonderful, and that book is great. I would not so much say that he is voting for rationality and moral decision-making as much as he’s being the cautionary voice saying, let’s not get too carried away with all the bandwagon excitement about empathy, where that’s just like the buzzword on everyone’s lips. Because, as he very rightly points out, there’s a temptation to decide that empathy is a virtue in and of itself. All you have to do is feel badly for the person, and that’s the danger of thinking empathy is so wonderful and the key to a much more peaceful planet and all of that. And the key issue is not whether you are empathically feeling somebody else’s pain and the nuances of that, but whether that empathy actually gets translated into doing something, into a compassionate act.

0:18:15.7 RS: And the thing that he’s good at pointing out is in a lot of circumstances, not only does empathy not lead you to actually acting upon it, doing the right thing when that’s scary or grave or whatever, but that certain types of empathy make it even less likely that you’re going to do something about it because you’re so consumed with the pain of you feeling that other person’s pain.

0:18:41.0 SC: Well, and one point he seems to make very effectively is that if we’re not very good at empathy, we are empathic for people like ourselves in the same position, in the same race, etcetera, and you sort of make similar points in your book, and you do use the phrase or the label the anterior cingulate as part of the brain that is responsible for these decisions.

0:19:06.6 RS: Yeah. And here’s one of these like all-time depressing findings, anterior cingulate, an obscure but totally cool part of the brain, it’s got something to do with empathy and pain. Pokes, your finger gets poked with a needle while you’re in a brain scanner, your anterior cingulate activates, ouch, now instead, watch the finger of your loved one gets poked with a needle, anterior cingulate activates. You are literally, as far as those neurons are concerned, feeling that person’s pain as purely as if it’s your own.

0:19:40.3 RS: But where the depressing stuff comes in is show people film clips of, say, somebody’s hand being poked with a needle, and if that hand has a different skin color from your own, on the average, there’s less activation of the anterior cingulate. In other words, not everyone’s pain is equal. And we bring all sorts of biases that are the outcome of everything that had brought us to that moment, many of which we have no conscious awareness of, and most of which, we have no conscious control over.

0:20:13.7 SC: Right. My counterargument, and I’m curious to see what you think about this, was simply that very often, when we think we’re being rational, we’re just being empathic in a bad way. We’re sort of not recognizing the pain or the experience of people who are very unlike ourselves. So rather than saying, “Don’t listen to your empathy,” the slogan should be, “Get more rational empathy, in some sense.” Is that even a reasonable aspiration?

0:20:39.5 RS: Yeah. Absolutely, or the way… That’s addressing one of the problems with, “Oh, empathy is… All you need is empathy,” which is that you are bringing your only filters as to who’s paying counts for more, and people who are familiar, people who are local, people whose pains are like ones that you’ve experienced. So that’s where rational empathy helps. The other component where empathy is not enough is one that calls for what I would think of as detached empathy. One of the problems with empathy or feeling somebody else’s pain is the pain is painful, whether it’s your pain or their pain that you’re now feeling. And if the empathic pain is severe enough, the logical thing is to say, “I can’t take this anymore and I’m getting out of here. I’m going to turn the page. I’m going to decide it’s not really my problem. I’m gonna decide somebody else is gonna take care of it.” The more viscerally painful feeling somebody else’s pain is, the more likely you are to wallow in how painful it all seems, rather than being able to go and act, let alone act in a reasoned, rational way.

0:21:54.1 RS: And there’s a fabulous experimental read-out of this. If you’re sitting and you’re watching somebody else going through something painful, and your response is to increase your blood pressure like crazy, you’re the sort of person who’s gonna sit in there saying, “Oh, my God! What were if this was happening to me? This would be so awful, I can’t take this anymore. I just have to look away.” On the other hand, if you could empathically note somebody else’s pain and your blood pressure doesn’t go up a lot, that’s a predictor of the ones who can actually act upon the other person’s pain, rather than responding to how painful their own empathic pain is. And what that takes us to is on one hand, a version of getting doctors sort of thick enough of scar tissue to not feeling the pain they’re inflicting on their patients in order to do good. Another version of that is sort of a Buddhist detachment about what empathy is. Empathy is not because, “I am feeling your pain and it is so painful.” Empathy is, “It’s not a good thing this is happening to you. And I can do something to alleviate it, so it’s self-evident that I should.” And that’s subversion, which sounds much less exciting than heart-warming Kumbaya sort of empathy, but if what empathy is mostly doing is making you lick your own empathic wounds, it’s not very useful.

0:23:29.8 SC: Which brings me to the other thing that I thought that this discussion brings up, which is: What are sort of the actionable intelligence here? How can we use this view of how we rationalize our decision-making, both to make better decisions, but also to talk other people into changing their minds? Should we try less hard to aim at facts and reason and logic and go right for the gut? Or is it more subtle than that?

0:23:57.1 RS: Unfortunately, I don’t think it’s any more subtle than that.

0:24:00.1 SC: Not more subtle, okay. [chuckle]

0:24:01.3 RS: I think in lots of ways, if the last four years could be summed up as the main take-home lesson for rational, careful thinkers with a respect for facts, blah, blah, one of the things that we’ve been taught over these last four years is you can’t reason somebody out of a stance that they weren’t reasoned into in the first place. If they got to where they are out of fear, out of anxiety, out of resentment, out of envy, out of a sense of being peripheralized, those things, you can’t talk to them about how what they’re advocating actually is going to make things worse for them. You can’t reason people out of stuff that is just based on the most visceral of emotions because those emotions are usually coming from people who’ve gotten some crappy deal along the way.

0:25:00.4 SC: And presumably, those people include ourselves. [chuckle] Is there something that we can take away for our own decision-making? Presumably, many of my decisions, which I perceive as perfectly rational, are secretly driven by my anterior cingulate or some equivalent organ in my body.

0:25:17.2 RS: Yeah, and that’s where you get to philosophers, God help me for quoting, but people like John Rawls basically said, “If you’re gonna decide if a moral act is okay or not, you’re not allowed to know who the actor is and who the recipient is, and if it’s you in it because the second, there’s a me in it or someone who reminds me of me, conscious or otherwise, yeah, all of us have the same problems. All of us are suffering from making decisions in life that we think of as highly cognitive that instead reflect the tumult of viscera that have gotten us to this point.”

0:26:05.3 SC: And it’s not just this or that organ in our brain. You talk in the book about the importance of hormones, of testosterone, oxytocin, etcetera, where our brains are floating in this bath of chemicals that have a huge effect on how we behave.

0:26:19.8 RS: And again, where we have no idea what’s happening.

0:26:22.6 SC: Right.

0:26:25.2 RS: Okay, here’s one of my favorite sort of testosterone studies. Where… What you see is… What does testosterone do? It makes you aggressive. No, it doesn’t make you aggressive. What testosterone does is make you more sensitive to queues that would trigger aggression, and new queues that you have socially learned. So testosterone makes you more rotten to people who you’ve already learned, socially, you can be rotten to and get away with. It doesn’t make you take on Bill Gates or something. So it’s more subtle than that. But it does perceptual stuff. So there’s this long-standing dogma that testosterone will make people’s analytical, math, geometric skills better. And you give guys testosterone without them knowing it, and it doesn’t make it better. However, they decide, they think that they are performing better than they actually are. Testosterone makes you less accurate at assessing risk, and less accurate at accepting feedback about your own performances, and it makes you cocky and bull-headed. That’s a very subtle effect because you’re not gonna sit there and say, “You know, I’m feeling real confident right now, and almost certainly that’s because that’s been doing something to potassium channels in my amygdala.” No, you decide why absolutely. Your army is going to be at their capital within two days, so let’s for go it, let’s invade, by all means.

0:28:00.9 SC: And you can see why constant exposure to these kinds of ideas would erode someone’s belief in free will.

0:28:08.6 RS: Yeah. And in some ways, where I think it has to do with the most, and all of this is said, not only am I a free will skeptic, I don’t believe there is a shred of agency that goes into any of our behavior, so that puts me out of the lunatic fringe of the range of philosophers. And there are scientists thinking about this. But in terms of this stuff, where this issue of, “There’s more stuff going on than we think”, subterranean biological forces, who I had no idea that had anything to do with it, it’s out of your control. The realm where it is most important is when it comes to behaviors that we judged harshly. That we punish people for, that we condemn people for. And the lesson that I pound into the heads of my students over and over is, 500 years ago, in virtually every European country, if you had an epileptic seizure, the best doctors around had a diagnosis for you, as to what caused the seizure, and the seizure was caused because you were consorting with Satan.

0:29:22.0 RS: And they had an absolutely clear neurological intervention, which is to burn you at the stake. And somewhere along the way people learned, “Oh no, it’s actually a disease.” And somewhere along the way, they stopped putting people with epilepsy in psychiatric hospitals. And somewhere along the way, people started developing laws that distinguished between who a person is, and what a seizure might do to them in terms of the ability to drive only once the meds have kept you seizure-free for a certain length of time. You sit somebody down today and say, “Wow, can you imagine somebody having a seizure?” and you’re saying, “Yeah, that’s because you’re sleeping with Beelzebub.” And they’ll say, “Oh my God, that’s ridiculous.” Wow, people used to believe that. People are going to look back on how we think of people with bad self-control, people with an inability to feel somebody else’s problems, people who are remorseless, people who are cold-blooded this or that. And it’s going to be as misplaced of attribution that we have now when saying these are attributes that are deserving of punishment, as people saying that epileptic were consorting with Satan.

0:30:40.2 SC: And the levels of various hormones in your body, if they do affect your behavior, which they certainly do, would be an example of something somewhat beyond your control, which has a big effect on what you do in the world.

0:30:52.0 RS: Absolutely. So what’s happening in your hormone levels in the hours to days before you have to make that decision of whether or not to pull a trigger, or whether or not to make this empathic gesture or whatever, hormones are absolutely playing a role in it. Not only in affecting your behavior, but in your ability to assess the outcome of the behavior, assess the feedback from it. That’s absolutely a case. Another thing, as long as we’re still in the domain of the previous couple of hours to days before a behavior, is all sorts of sensory stuff. Both the external sensory world and the internal one. If you are in pain, if you were tired, if you are hungry, related to that, if you have low blood glucose levels, you’re gonna cheat more in an economic game. You’re gonna be less charitable, you’re gonna be less trustworthy, you’re gonna be less generous, you’re gonna be more likely to punish somebody for their norm violations if you are in pain at the time.

0:31:58.8 RS: Or, if you’re sitting and you’re playing some online economic game, and for a tenth of a second, there’s flashing up on the screen, a pair of eyes staring at you where that’s so fast, you’re barely even conscious if you saw something, you’re less likely to cheat because you’re being monitored. If somebody sits in a room, and there’s a bad smell in the room, a smell of garbage permeating in there, people on the average become more socially conservative in the decisions that they make. Because they’re unconsciously being primed to feel a little bit disgusted. “Why am I feeling disgusted?” says your implicit unconscious brain, “I know, it’s because when those people do that behavior, it’s wrong, wrong, wrong, and disgusting. There, I’ve just made a moral decision.” And no one is gonna sit there and say, “Oh, it’s because the room smells badly, and there’s neurons in a part of my brain that processes gustatory disgust, that happens to also do moral disgust in humans, and it can’t tell the difference, so pay no attention to my assessment just now.” Instead, we come up with a reason why. “You know, I used to think it was okay when people do that, but it’s just striking me, it’s wrong how they do that.” Look at how many hours it has been since a judge has eaten a meal, and in one extremely well done influential study, that’s the single biggest predictor is whether somebody… A judge is gonna send somebody back to jail, or grant them parole. Are you hungry or not?

0:33:37.4 SC: I wonder if we could study my podcast episodes versus when I’ve had lunch and see whether I have different attitudes towards the guests, but I wonder maybe you know, I once heard, and I’m not sure whether this is an urban legend or not, but I once heard that training as an economist makes you more rationally self-interested and less altruistic because you’re taught that that’s how people behave. Do you know if that’s a true thing? Or just a legend?

0:34:02.8 RS: No, that’s absolutely the case. It’s one of the professions, or if you really wanna do it elegantly, there’s always the issue of, Well, maybe the person became an economist because they were already a self-interested, rational, maximizing machine. You have somebody who’s an economist, and either you prime them to talk about their family life, or you prime them to talk about accounting, and when you make them identify more with being an accountant, that’s when they show more cut-throat game theory play. In the same way, you get somebody to play a version of the prisoner’s dilemma, and if you describe it as the cooperation game, you get totally different game play out of most people, than if you call it the Wall Street game.

0:34:50.8 SC: It does make you think, but I don’t want one other thing to get lost too quickly, when we were talking about testosterone and how you were undermining the sort of conventional wisdom that it’s all about aggression, and that’s something you do over and over again, there’s something you were taught is true and it’s not quite as simple as that. Does that whole fact that those un-doings are so common in this field make us worry a little bit about the implications we do draw from experimental data? The brain and behavior are very complicated things. How do we know when we’ve gotten it right?

0:35:24.7 RS: Yeah, especially since, I don’t know, some version of Moore’s Law every decade, the amount of our knowledge about the brain doubles, just judging by… And the number of papers published that are actually not true that nobody knows yet. It’s why all of us with our Joe Science detective badges and stuff say we don’t find out facts, we have temporary assessments of how credible we think our current hypothesis is, and we better be willing to give it up without a fight if facts contradict it. Yeah. Absolutely.

0:36:03.2 SC: Okay, so we have processes in our brain that work on time scales of, what should I say, seconds? Is it is short as milliseconds? How many, tens of milliseconds?

0:36:13.9 RS: Yeah, you look at… Here’s another set of those incredibly depressing studies. You stick somebody in a brain scanner and you’re looking at the amygdala, one of the villainous parts of the brain. It’s about fear, it’s about anxiety, it’s about aggression. That’s interesting, you can’t understand the neurobiology of injuring other people outside the context of the neurobiology of being terrified out of your wits. But what you see is, now the amygdala’s part of assessing, is this a friendly face? Is this a threatening face? What’s the emotions, is there no emotion, and it does it really quickly.

0:36:56.8 RS: But a study finding that has been replicated a bunch of times now, which is so damn depressing, is you stick somebody in a brain scanner and you’re flashing up pictures of faces and they’re each up for a half second or something, and then your average person, you flash up the face of somebody of a different race, and the amygdala responds in 60 to 80 thousandths of a second, before you’re even consciously aware of what you’re looking at. Oh my God, that’s the most damn depressing thing on Earth and furthermore, more studies show the more your amygdala reacts to the face of an other simply because their skin color is different, the more likely you are to mistake their cell phone for a handgun in all sorts of simulation games and shoot them, whereas you’re less likely to do that of somebody of the same skin color as your own. Oh God, that is so depressing. That is playing out in a fraction of a second. Yeah. Is this hopeless? No, because the statement that I said before, on the average most people do this. There’s exceptions, like 30% of people don’t do this. And all sorts of stuff that predicts that you are somebody where skin color is not gonna be a tenth of a second us-them category by which you divide the world.

0:38:25.0 SC: Do you know if you can train yourself to change that in any way?

0:38:30.0 RS: Yeah, and this is like a whole world of what to do with our implicit biases, and when you look at the people who don’t have those amygdaloid responses, who are they? People who grew up in a racially diverse neighborhood, okay, skin color is not a relevant us-them divider. My guess is they have their biases working in some other domain. People who had a close intimate relationship with somebody of another race along the way, that breaks them… All of those are okay, so here’s your solution for your implicit biases. Go back to your childhood, again, be brought up in a different neighborhood, that’s not very useful. Two things that are though, and can work fairly rapidly, is one thing that comes out of this whole world of implicit bias tests. The Implicit Association Test, Harvard’s Psych Department, where it really arose from… You could go online there and find out just how scarily implicitly biased you are about all sorts of stuff, testing things that you cannot game the system.

0:39:35.5 RS: But one of the useful things is when you make people consciously aware of the implicit biases that they are showing. Does this make the implicit biases go away? No. It makes you put more conscious effort into slapping your hand over your mouth before you say something disastrous or equivalent of. The other thing that is very reliably good at this, and this is work that was pioneered by Susan Fiske at Princeton is, you get somebody in the brain scanner, and this is the circumstance where there’s a picture of a face of an other and the amygdala activates, and, Oh damn, this is hopeless. If you have primed the person beforehand to think of that face as being of an individual, Is this somebody who likes broccoli or not? Is this somebody who likes Coke or Pepsi? There’s been a whole lot of ethnically bloody wars fought over Coke versus Pepsi. Totally benign things, but force you to begin to unconsciously process that face as an individual, and you blunt the amygdaloid response. And that’s exactly what it is, because bias is a heuristic shortcut for us to decide we know all about somebody, because we think we know all about the class of somebodies that we have attached them to in our heads.

0:41:02.8 SC: Maybe that’s an important thing to emphasize, both… Or two important things. One, that these biases we have, these heuristics, do serve a purpose. They’re not completely brain-dead. They’re actually functional in some way. But, number two, they’re not determinate either. We can… There is some room for system two in our cognitive capabilities to overcome that first initial unconscious response.

0:41:26.4 RS: Great. And here’s an example of system two in action. So you take people and you’re doing the same routine in a brain scanner, you’re flashing up pictures of faces, and you flash up an other race face, and the amygdala activates, and, Oh God, that really sucks, and the person and some visceral level is feeling the aversiveness of that response. And what you see is in a substantial subset of people, I don’t know, maybe 50% or so, what you see is, a second or two later, there is activation of a part of what is called the frontal cortex, which is about conscious regulation of behavior and of thoughts and of emotions. And every time you feel like telling somebody that the dinner they prepared at the dinner party is the most repulsive thing you’ve ever eaten, but you don’t say it, is because your frontal cortex is working properly.

0:42:25.9 RS: So what you see is two seconds later in about half of people, the frontal cortex activates. What is that? That’s you feeling bad that that was your visceral response. That’s your, Oh my god, don’t say that, or, That’s not who I am, or, That’s not who I wanna be. Who are the ones who activate their frontal cortex two seconds after having an implicit racial bias? People who categorize themselves as liberals. Conservatives don’t show that because there’s no dissonance for them. Two seconds later, they’re not finding anything wrong if that was the visceral response. So it’s not just the conscious sort of system two jumping in there, Hey, don’t think that way, sort of stuff, but the fact that we all differ as to when we engage those sorts of conscious executive monitoring sort of routines in us.

0:43:25.5 SC: So we have these sort of sub-second timescale responses, which we can modulate or even override if we want to, and then what was this time scale you associated with the hormone system, with the endocrine system?

0:43:41.5 RS: Hours or a bunch of minutes to a few days or so. Your testosterone levels this morning, if you’re male, are going to have something to do with how likely you are to decide that somebody with a neutral facial expression actually has this threatening facial expression. Your oxytocin levels this morning will have something to do with how trusting you’re gonna feel in an economic game. So playing out in that sort of time course. But that’s just the smidgeon of what we have to take into account, because all we’ve gotten to is the biology of the last couple of days that have brought you to this moment.

0:44:19.3 SC: Exactly. So let’s go back in time further. Let’s just be ambitious here and talk about our development during our lifetime. And one of the favorite factoids that you lay down to us in your book is that our frontal cortex, to which we just gave great props for overcoming our implicit biases, isn’t even fully formed until we’re 25 years old. So I’m shouting out to all of the Mindscape listeners who are under 25 out there. And just think of how smart and cognitive you’re going to be in just a few years.

0:44:55.1 RS: Yes. Although, as can be seen, it’s a double-edged sword. Frontal cortex, it is so cool, it does long-term planning, it does emotion regulation. It’s the most recently evolved part of the human brain, we’ve got more of it than any other mammal out there. It’s totally great. It’s the last part to fully mature. Some parts of your cortex are fully wired up when you’re a month old kind of thing. Frontal cortex, 25 years. One implication of that is, that gets us into trouble when instead we’re 16 instead of 25, because the parts of your nervous system that are about thrill-seeking and sensation-seeking and risk assessment and conformity to peers driven by stuff like the neurotransmitter dopamine, that stuff is fully online by around puberty. And then the frontal cortex is still futzing with the construction manuals for another dozen years or so. That’s why juveniles act in juvenile ways. That’s why adolescence is about these excesses of emotion and all of that, and then your frontal cortex catches up.

0:46:09.8 RS: So you then say, “Wow, you can fully maturely wire up some of your cortex in your first year of life, and your frontal cortex takes 25 years.” Is that just a tougher construction project? Are you having to make fancier types of neurons or there… Then the rest of the cortex, nah, it’s the exact same kind of cortex as in the rest of the brain. Why is it a 25-year project? Because it better be a 25-year project. If the frontal cortex has the job of making you do the right thing, when that’s the harder thing to do, it’s got to spend 25 years learning what counts as the harder thing to do. In your culture, in your peer group, in your whatever, I mean, we’re all taught, thou shalt not lie, but here are the circumstances where you lie, and lie if grandma gives you a toy that you already have, tell her you don’t have it. Thou shalt not kill, but what we actually mean is you should not kill one of us. If you kill one of them, we’re more likely to meet with you and give you an award afterward. It’s not trivial for your cortex to learn what the hypocrisies and what the rationalizations are of the social world in which you live, and genes can’t specify that by the time you’re 10 months old. That’s gotta have a third of your lifetime spent learning what the spoken and unspoken rules are of the world in which you’re trying to navigate.

0:47:42.9 SC: And when we talk about the frontal cortex developing in this way, what exactly does that mean? Or is it more neurons coming online, or is it rewiring the neurons that are there?

0:47:53.5 RS: This is one of the cool things about brain development that might kind of transform your thinking about it. Okay, a developing brain, a brain that’s doing a good job at getting ahead of the pack, just in time for the SATs when you’re a teenager or whatever, you’re just packing in neurons like crazy, you’re packing in more synapses than anybody else out there. That’s exactly the opposite of what you see. You do not have your most neurons and most connections and most complex wiring when you are 25, you have it when you’re about 12 or 13.

0:48:31.3 SC: Oh, no.

0:48:32.1 RS: You have more neurons then, than what you’re gonna have as a young adult. What’s adolescence about? It is not generating new circuitry, it’s pruning out the circuitry that’s sloppy, that’s inefficient, that’s turning out not to work to your benefit, that’s not… What you’re doing is cutting away the excess. A fully mature brain in terms of numbers and neurons, what it’s about is being lean and mean, rather than being overflowing its building blocks. So a lot of what’s going on in adolescence is getting rid of the extraneous stuff and making the right decision as to what counts as extraneous.

0:49:14.2 SC: I remember I was struck when I read about the neural system of C.elegans, of the little roundworm, right. It has, whatever it is, 300 and something neurons, do you remember the number?

0:49:26.0 RS: Two, I think it is, 302 or 306.

0:49:28.2 SC: 302, depending on what gender it is. But, so what struck me was not that number, but the fact that there was a specific number. It wasn’t like 300 plus or minus 10, right. Presumably the human brain… Different human brains have different numbers of neurons? We have 85 billion or something like that, or is it really… Can we sort of correspond each neuron to a particular kind of thing and everyone has exactly the same wiring at the beginning?

0:49:57.9 RS: No, absolutely not. And one of the best lessons about how genes are not deterministic about how our brains function is you take identical twins, and at their moment of birth, their brains are already doing gene regulation differently. Their metabolic profiles in a scanner are already working differently, because even if they’ve been in the same womb, they just had nine months of subtly different or not so subtly different fetal environments. And that’s got something to do with producing variability. In some ways, the two key questions for making sense of any of this biological patterning stuff is why is it that we all have brains that are similar? And why is it that we all have brains that have nothing else out there that’s identical to it?

[laughter]

0:50:55.4 SC: So that’s it… I presume you’re not gonna to tell us the answer to that question because this is a very complicated one and we’re learning as we go.

0:51:02.6 RS: Yeah.

0:51:03.8 SC: But it does… For the question of understanding reasons behind our behavior, the lesson presumably is that there are things that went on in the womb in childhood as ongoing well past your childhood, well past puberty, that affected what your brain is and how it’s wired, and therefore who you are.

0:51:26.9 RS: Absolutely, and here’s like two studies, both of which are outrageous and should have you up screaming about how we can run a society with facts like this and ignore them. The first one is a sledgehammer one, which is about 25% of the people on death row in this country have a history of concussive head trauma to their frontal cortex. And when the frontal cortex gets damaged, you don’t have somebody who is violently out of control because they’ve got a rotten soul, you’ve got somebody who’s brakes don’t work. And talking about punishment and retribution and evil and anything like that, it makes as little sense there as to talk about a car whose brakes have failed.

0:52:15.8 RS: So that one should totally up-end one’s thoughts about the criminal justice. The other one is just as much of a, “Are you kidding me? This is what the world is like?” But it’s a more subtle one at first pass. So you look at what hormones have to do with brain development, and there’s a class of hormones that are secreted during stress, they’re called glucocorticoids, they do a bazillion things in your body. And one of the things they do is they screw up development of neurons in your frontal cortex. You have a lot of stress early in life, and your frontal maturation is going to be impaired. Sufficiently so, this finding replicated top people in the field, where by the time a kid is five years old, if they have been stupid and foolish enough to have picked the wrong families to have been born into, if they’re being raised in poverty, on the average, the levels of glucocorticoids in their bloodstream are going to be higher than kids of higher socioeconomic status.

0:53:24.7 RS: Their frontal cortex is gonna be thinner than the more lucky SES kids who’s gonna have a lower metabolic rate, and is already predictive of a frontal cortex later in life. It’s gonna have a harder job of doing the tougher thing when it’s the right thing to do. By age five, people should be rioting at the barricades, because early life adversity has a hell of a lot to do with how you are sculpting the nervous system you’re gonna have for the rest of your life, as does early life stimulation, and early life love, and early life security, and early life insecurity and all it’s variants. All of them are affecting how your brain is constantly being wired and renovated in upkeep and they all leave a footprint.

0:54:14.8 SC: And unlike some of the results that you’ve been talking about in some sense, this affirms what you might think. That how we treat kids has a very lasting effect on who they grow up to be.

0:54:27.9 RS: Well, it affirms how we think about it. It certainly runs counter to how people thought about it for a long, long time in the 1930s. If you had a kid going to a pediatric ward in a hospital, well, the father would never be allowed to set foot in there and the mother would be allowed in like 15 minutes once a week or so. Because mothers aren’t useful, what they do is they provide nutrients and we’ve got the nursing staff to do it and touch, and holding, and care, and comfort. And then 1950s, people learn stuff like that matters. And then people learn like, are you growing up in a neighborhood being surrounded by bars or surrounded by libraries? That’s gonna wire up your brain in different ways. Are you… All sorts of stuff. People are constantly learning much, much more subtle factors in early life, are having to do with how the whole system is being wired up.

0:55:29.6 SC: I think that’s fair. I think that I’m sort of taking certain things as just given an obvious one in fact. Even just a few years ago, they were not that obvious at all, so good for you for being a little bit more accurate there. But let’s keep going backward in time, so we have our childhood, and our subsequent development, we have our hormones or and our amygdala and so forth, and there’s stuff going on even before we’re born that presumably we can’t be blamed for, but that goes into our genetics and the rest of our heritage, that also affects how we behave.

0:56:00.7 RS: Yeah, because environment doesn’t begin when we’re born. Environment starts as soon as you start in somebody’s womb. And by the time you’re born, you’ve just spent nine months having a very intimate relationship with the bloodstream of your mother. The nutrients in there, the hormones, the toxins, the environmental carcinogens, who knows what? The whole long list. And what your fetal life is like has something to do with how your brain is wiring up because it’s giving some answers to what the world out there is gonna be like. The flagship observation of this is one, which is just in every textbook out there, and we’re accustomed to you learn something about lab rats and then you learn about it in your monkeys, and then maybe you could see the same thing in humans.

0:56:52.5 RS: This was an observation that started with humans. I944, Germany, Nazis occupying the Netherlands, and during that winter there was an uprising of the Netherlands that was crushed by the Nazis and as part of the punching for it during that winter, all of the food in Holland was diverted to Germany. And for three months, basically everybody was starving, what is known historically as the Dutch Hunger Winter and like 30000 people starved to death. And up until that point, people had a okay diet, a war time diet, and then the other end the allies came along and liberated the Netherlands and suddenly people go back to having a decent diet and you’ve got three months of starvation. And it turns out if you were a third trimester fetus during the Dutch Hunger Winter, your body forever after decided, you know what, there’s not a whole lot of food out there, so any food I get, I’m gonna store away, and any salt I get, I’m gonna retain.

0:58:00.7 RS: And what happens is everything else in equal 60 years later, you have almost a 20-fold increased likelihood of having diabetes, and obesity, and hypertension. If you were a second trimester fetus, that wouldn’t happen, that’s not… When your body was deciding, okay, how much food is there out there? If you were a new born, that doesn’t happen either. If you were a second trimester fetus during the Dutch Hunger Winter, you have a great increased risk of suffering from schizophrenia in adulthood. If your mother was depressed during the time that you were a fetus, you have an increased risk of depression for the rest of your life, because it’s got something to do with how reward pathways in your brain were wired up. Fetal environment is very, very relevant to our notion that environment shapes us, and we all differ as to how lucky or unlucky our field environments were that we happened to stumble into by chance.

0:58:58.9 SC: And what about the environment environment, for our ancestors growing up in different parts of the world, different climates, different cultures? To what extent do those sort of differences in the selection of people from whom we’ve drawn our genes end up affecting us today?

0:59:17.4 RS: Well, what you see is one of the dictums out there is genes co-evolved with behavior, co-evolve with brains, co-evolve with cultures, and they’re all influencing each other. What you see is some really amazing stuff out there, I love this literature just because it’s one of those where it’s gotta stop you in your tracks with the oh my God, I had no idea biology had something to do with that. If your ancestors were nomadic pastoralists wandering deserts or grass lands with cows or camels or sheep or something, versus if your ancestors 400 years ago were farmers, if you’re a descendant from pastoralists you are much more likely to murder somebody today over a perceived honor violation. You are much more likely to…

1:00:14.1 SC: I shouldn’t laugh.

1:00:14.5 RS: Have a clan vendetta. You are much more… You are a descendant of a culture of honor, people who were pastoralists invent cultures of honor. How come? Because if you’re a farmer, nobody can come and steal all your crops one night, if you’re a hunter-gatherer, they can’t come and steal your rainforest, they can come and steal your cows at night. And as some Bedouin saying, classic nomadic pastoralists, If they come for my camel and take it and I don’t do nothing, tomorrow, they’re gonna come for the rest of my camels, and the day after they are going to come for my wife and daughters. What you do is, you have maximal retribution when you think there is an honorific violation. And if you are a descendant of those cultures, you are more likely to have honor-related acts of violence.

1:01:05.1 RS: If you are a descendant in modern China these days, of people who, two generations ago were wheat farmers rather than rice farmers. Rice farming is this huge collectivist thing where you have 10 villages that have been maintaining the same irrigation system for the last thousand years, and everybody works collectively. Wheat farming is much more individualistic. You find wheat farmers up in the north, you find the rice farmers in the southeast, the sort of monsoon rice patty areas. If your grandparents were wheat farmers, you are more likely to be divorced than if your grandparents were rice farmers. You’re more individualistic. You’re more likely to have filed for a patent.

1:01:53.0 RS: If your ancestors lived in a desert, you are more likely to have a monotheistic religion. If they were from the rain forest, you are more likely to be polytheistic. Just lists and lists of these. My God, how does this happen? How does what was going on 400 years ago translate into things like this? Because culture affects child rearing practices, and child rearing practices affect the brain you wired up, and that will affect the cultural practices which you value and then propagate to the next generation. And you see stuff like, how’s this for as trivial as it gets? You take mothers from collectivist cultures, and most of the studies are of people from Southeast Asia, where there’s a tremendous group mentality, and you take people from the most extreme of individualist cultures, and the US, of course are the poster children for that, and within minutes of birth, mothers from these two cultures on the average sing lullabies to their newborn at different decibels.

1:03:04.5 RS: Mothers from collectivist cultures sing softer than mothers from individualist cultures. And that’s just the first step. You’re seeing differences between those two on the average between how much of each day you’re in physical contact with your kid. What’s the average lag time before you pick your kid up when they’re crying? At what age do you wean them? At what age are they sleeping in a room by themselves? All you’re doing from the very first step there up until in adulthood and seeing what your culture is handing out awards for, every step of the way, you are propagating the cultural values you were raised with that were passed on and that leave an imprint into your brain and your behavior and your genes and what you then pass on to the next generation.

1:03:56.8 SC: Well, you slipped in there “and your genes”, so I’m wondering, to the extent that these kinds of behaviors are passed down through societies or groups of people, I could imagine that’s happening either completely culturally through memes, if you like, in Dawkins’s sense, or I could imagine that there’s different selection pressures in different parts of the world for different kinds of genomes, right? Are we able to disentangle that kind of thing?

1:04:25.3 RS: With a great deal of work and a great deal of controversy, and a great deal of people who rush in where angels fear to tread, mainly because they have some ideological axe to grind. What you mostly see is, if you’re thinking about genes determining a lot of stuff about your behavior, you’re decades out of date as to the genetics, the behavioral genetics that you know. Over and over and over, genes are about our potentials. Genes are about our vulnerabilities. Genes are not about our inevitabilities. And you see this, for example, Okay, there’s this one gene variant, it’s got something to do with this neurotransmitter serotonin, and there are all sorts of reasons to think this gene comes in a couple of different flavors. Animal studies suggested if you had this flavor instead of that flavor, you were more likely to be violent, and that’s… ’cause the animal study showed that, lets study thousands of people from birth up to adulthood and track their genetics, and are you indeed more likely to have had a history of violence as an adult if you had that scary gene variant? And the answer was yes.

1:05:42.1 RS: Yes. Uh-oh, are we looking at genetic determinism? The answer was yes, comma, if and only if you were abused as a child. In other words, genes and environment interacting and the same traits that will give you a very well-developed frontal cortex with great emotional regulatory abilities, depending on one setting, what that’s gonna mean is you’re just gonna work on a front line, EMT, life-saving person around the clock and suppress all your exhaustion, or in another setting, it means that your brain’s gonna make you be really good and disciplined at being like a genocidal warlord.

1:06:32.3 SC: I guess for the… But there’s also the question quite closely related to this, of looking at differences in our ancestors 400 years ago, which is the number you just mentioned, versus 20,000 years ago. If there were a difference 400 years ago that still affected our behavior today, my bet would be that most of that transmission was cultural, whereas if there was a major difference 20,000 years ago, there’s sort of more room for evolution to work and our actual genomes to change.

1:07:03.6 RS: Absolutely. That’s getting into the range… I mean, dogma used to be, eh, 20,000 years, that’s a blink of an eye from an evolutionary standpoint. Twenty thousand years is enough for significant changes and change distributions in different populations, and genes having to do with melanism of skin color, genes having to do with whether as an adult you can digest milk products, genes having to do with your vulnerability to skin cancer, genes that… Just a whole array of that, genes having to do with developing modern capacity for language. Those are all genes that are developing really fast and through a lot of selective pressure, so yeah, that’s getting into the time range.

1:07:46.4 RS: So when you begin to look at where evolution has got us to, the obligatory soundbite at this point is you gotta remember, the last 20 years, and even the last 20,000 years, are a blink of an eye in hominid history, we’ve been around for a couple of million. We evolved under circumstances very different from that thing we invented like yesterday, which is agriculture and material culture, and we were just hunter-gatherers forever, and 99% of our time, we evolved due to those circumstances, and that makes for a brain which in many ways is not terribly well-adapted for the present.

1:08:29.9 RS: If I had to say the single biggest way in which that’s the case, is the vast majority of human history we’ve spent surrounded by people that we know and have known for a long time, and in fact are often third or fourth cousins. And it’s really only in the last 10,000 years with hamlets turning into settlements, turning into proto-states, kind of thing, that it’s possible for humans to live surrounded by strangers and to do something anonymously where no one will know you did it. For 99% of human history, there’s no such thing as doing something where no one will know that you did it, and all sorts of regulatory control evolved into those circumstances.

1:09:18.5 SC: I did have Joe Henrich on the podcast recently, who has been talking about the weirdness of the West and he has this new theory that a lot of it can be attributed to the church telling people not to marry their cousins, and that opened them up to mingling and free-associating with different groups of people, which created Western culture. Is that compatible with the kind of story you’re telling here?

1:09:41.7 RS: Absolutely, he’s great, and in fact, I was just about to cite him in the next sentence. Not that branch of his work, but a related one. There’s lots of different kinds of religions, there’s lots of different gods who have been invented out there, I don’t know, 6,000, 7,000 different religions. And one of the variables is whether or not the god or gods your folks have invented care about what you humans are doing. And what he and a collaborator at the University of British Columbia first demonstrated is in hunter-gatherers all over the planet, the god or gods they make up have no interest in human activities. They could care less what humans are doing. It’s not until you get people living in large settlements, it’s not until you get societies where people can interact anonymously, that you start inventing what are called moralizing gods. Gods who are watching. Gods who know who’ve been good for goodness’ sake.

1:10:45.3 SC: A little judgy.

1:10:46.1 RS: Gods who dole out punishment. Because as soon as you get to a range where you have a society where people could get away with stuff with anonymity, you’ve got to invent supernatural force as a constraint. And that’s incredibly important in terms of making sense of the values we have, about why are we here on Earth? Are we sinful or not, or beautiful or not, and is there an afterlife, and what counts as a good life? And all that reflects all sorts of ecological, biological, evolutionary, cultural, all intertwined influences that have got you to the point where you are.

1:11:28.0 SC: Well, I think it’s one thing to do as you’ve already done, to sort of locate a population some number of years ago and follow it through time and say that, compared to this other population, they behave differently, and maybe their genomes are different, depending on the timescales. But then there’s another layer we add on that, which is this explanatory story, right? The reason why you get honor cultures from pastoral societies is because cattle are vulnerable to theft. That part seems a lot harder to be scientifically skeptical about and really get right.

1:12:05.2 RS: Absolutely, because it’s kind of tough to do a 400-year experiment on, let’s take these folks and dump them in the Gobi Desert for the next four centuries, whereas these folks go to the Amazon and let’s meet at the end and see how things… You can’t do that type of science that labs scientists respect, which is experimental stuff. You do more descriptive, you do sociological, you do what winds of being the gold standard is, if it winds up being predictive. Here, first time this hunter gatherer culture has been studied, and do they indeed show these traits that are higher than expected chance. Do they… That’s the best that you can do. And sometimes that’s great. And teleology is something that all scientists like to think with, but never like to admit to, because things happen for a reason. And if you could think what those reasons are, that gives you a lot of insight. But some of the time you’re just making up Just So Stories. Here’s why the zebra got its stripes, here’s why most cultures on earth have male domination, here’s why… It’s natural and got selected for and yeah, you gotta be really careful that notions, explanations, cause of stories that you’ve come up with can be falsified and are actually supported by data rather than being ideological.

1:13:34.7 SC: Well, you said, speaking being ideological, maybe there’s harmful and helpful ideologies. You started out at the beginning by saying that human beings in some ways have some of the worst traits in the whole animal kingdom, but in some other ways, have some of the best. Given all of this better understanding that we have now about behavior than we ever did, how does this help us become better? How do we turn this into an optimistic picture for the future of humankind?

1:14:04.7 RS: Well, we learn about the ways in which we’re just like every other animal out there, with the same blueprint and the same hormones, and the same enzymes, and the same transcription factors, and incredible conservation. And we see it’s the same parts of the brain, and the same hormones involved in violent behavior, involved in affiliative behavior. Wow, we’re just like all the other animals. And what we then have to be trained to do as well is as say, but hey, we’re secreting the same exact oxytocin when we’re reading about the pains of the character in a novel we’re reading that a mother chimp would secrete when her infant is injured. We can do it about stuff that doesn’t really exist.

1:14:56.1 RS: We could do to it for movie characters. We could do it for refugees on the other side of the planet, who we’re never gonna meet, where we don’t even know what their pheromones smell like or we’re… We can extend that. We have the basic wiring of violence of like half the other primates out there, but we could use it to kill someone whose face we’ve never seen, or we could use it to kill someone because they have different notions of what happens to you after you die, than you do. We have the same basic blueprint lots of the time, and then we use it in ways that are totally novel. And I think that’s where we have to be very conscious of when we are using stuff that’s been around for 20 million years of primate evolution, 70 million of mammalian, 300 million of vertebrate evolution, and we’re using it in a way that just got invented last week. And to be very on guard on the ways in which that will set us off the rails.

1:16:00.0 SC: Right, and so the thing that… I think you’ve said this, but I have trouble understanding what other people said when I have an opinion already that is very close to that. I ended up just putting in my own words here. So this ability of human beings to conceptualize the future, especially sort of counter-factual, hypothetical future scenarios seems to be, if not unique to humans, at least, much better developed in human beings than elsewhere. I’ve talked to various people in the podcast, including Karl Friston about this and Malcolm McIver and so, is that what you’re suggesting we take advantage of? Is that our secret to making ourselves better?

1:16:41.6 RS: That’s one of the ones. Another one is to be aware. One version the future is a certainty that people in the future are gonna look back at us and be as appalled as we when we looking at it. The value systems of medieval peasants. So be very cautious before you decide you know what’s going on. Another thing we should be aware of, if I had to pick the single thing that is conserved in how our brains are constructed, that’s in line with every other social animal out there, that is the cause of more human misery than like one can imagine, it’s the fact that like every other animal out there, we have automatic, implicit, lightning-fast, classifications of people as to whether they are an us or them. And we have automatic, lightning-fast, conclusions that we like the us as a whole lot more than the thems. We are like every other primate after all this but where we’re different, we have multiple us them categories in our heads at the same time. And while it may be inevitable that we as primates make ‘us’ ‘them’ dichotomies, it’s incredibly easy to manipulate us as to which dichotomy seems most important to us at any given point.

1:18:10.3 RS: And the guy walking towards you on the street at night, who’s one of those and scary, and maybe I should be all anxious and you’re amygdala is firing like crazy, if the next day you’re sitting next to him in a sports stadium and you’re both chatting the same idiotic chant in favor of your team, that you’d give up your life for your brother at arms kind of thing. We are just like other animals, until the ways in which we are very different, and what culture has often provided is ways to manipulate the hell out of us as to exploiting those uniqueness and for better, and an awful lot of the time for worse.

1:18:52.5 SC: I just saw the video online, one of these nature videos where a lion, a lioness, a female lion was hunting and was able to separate out a new born water buffalo from the pack, so a perfect week little snack to snack on, but then rather than snacking on it and finishing off its prey, the lioness adopted it, started taking care of it, and the explanation obviously given after the fact, no one interviewed the lioness, but the idea was, well, maybe she had just lost her own cubs and her maternal instincts overwhelmed her hunger instincts, and maybe that’s a paradigm for how we can switch back and forth between different ways of conceptualizing others, even within the constraints of our biological responses.

1:19:40.7 RS: Yeah, because if you work hard enough, you could find the commonalties… Oh my God, that thing does not look like Simba at all when he was just given birth to… But still for a buffalo, they’re kind of cute and their forehead is kinda all rounded and they got a short muscle, “Oh, look at those big eyes bulging out, I just wanna take care of this one because I’m a peri adolescent female and my hormones are making me all confused as to who I should feel maternal about.” Absolutely, and the minute you can have instances like that, it’s showing that we are not alone in doing other animals versions of contributing money to a conservation group, to save some other species instead of our own, let alone members of our species who are close relatives.

1:20:31.8 SC: So let me close, wind things up with a completely unfair question.

[laughter]

1:20:36.2 RS: Okay.

1:20:38.2 SC: Do you think, given that this a very complicated story of why we make the decisions we do, how we behave like we do all of these different causal factors going all the way back, and you emphasized over the course of our chat, how many of the experimental findings were kind of depressing in one way or the other, so do you think that people would be better… That there will be a better place if everyone read your book, if everyone knew more about the actual causal factors that go into our behavior than they typically do?

1:21:11.9 RS: Oh man, I could not have asked for a better question to set me up, to try to flog more but… Exactly, and the answer is no, but it wouldn’t help if everyone read that book or listened to a lecture about how the amygdala develops or some such thing, because once again, most of human misery is not due to rational decisions, most of human misery is due to rationalized ones. Again, you can’t reason somebody out of the stance they weren’t reasoned into in the first place. Once again, not a whole lot of human misery is due to somebody saying, “It’s okay to rob, it’s okay to steal, it’s okay to plunder.” It’s due to people who say it’s not okay to do those things, but here’s why I’m an exception today, here’s why my people are, here’s why my background makes me the exception, here’s why it really doesn’t count with me.

1:22:09.2 RS: We are running on the means by which we can make rationalization seem rational, thanks to our emotions to such an extent that I don’t know, everyone should go buy my book and use it as a door snob. It’s certainly not gonna bring in world peace.

1:22:28.3 SC: Well, I’m gonna be more on your side of people buying your book here, but I don’t have any empirical data to back me up but something makes me think that if more people were aware of how much of our everyday behavior was not completely rational, rule-based cognitive and how much of it was automatic, visceral, driven by heuristics that we’ve inherited from thousands of years ago, it would cast our decisions in the slightly different light. I think a lot of people stick to their guns about their decisions because they’re convinced that they’re rational, even if they’re not, and maybe selling a little bit of doubt in that conviction would be a good thing.

1:23:10.4 RS: The psychologist, Josh Greene at Harvard, who stated really well, that when people say, “We have a right to do that,” what they’re saying is, “I can only rationalize why I want to do that, I don’t actually have a rational reason why… I can’t tell you why I wanna do it, but I wanna do it so much that I am going to declare it to be a right.” That’s exactly a circumstance like this, and even broader sense, if you accept that we are nothing more or less than our biology, incredibility complicated biology from one second ago to 1 million years ago and interacting with environment, blah, blah, blah, if we are nothing more or less than our biology. And those are biological influences over which we had no control that brought us to this point.

1:23:56.9 RS: If you really, really, really believe that you can never feel justified in thinking you are entitled to anything more than anyone else, because whatever it is that you have done, which you believe has earned you praise your entitlement, you have nothing to do with… And if you really, really believe this stuff, you have no rational grounds forever hating anyone because they didn’t have a damn thing to do with whatever it is they did, no matter how horrific and hurtful it was, and if you really think those ways, this could be a very different world, and at the same time, like I could think those ways for about three and a half seconds at a time before I fall back into the much more inquiry and stuff, but if you really believe this stuff, those are the only conclusions you can reach.

1:24:47.1 SC: Well, couldn’t you just say, “I really like being a bundle of visceral heuristics, I’m just gonna go with it, I’m gonna lean in.”

1:24:56.5 RS: Yeah, except you then have to ask, so what are the circumstances that brought you to the point of liking it. Bundle of heuristics.

1:25:04.6 SC: Fair enough.

1:25:06.0 RS: The legal system can deciding that somebody intend to do that or not, and if they intended to, ooh you’re in trouble. The legal system never says, where did that intend to come from, that came from the combination of these 7 gene variants. This thing that happened during second trimester, these cultural values during childhood and the day that they got exposed to that like toxin when they were 18 and then got hit in the head.

1:25:31.4 SC: Well, I do appreciate your uniquely optimistic version of existential anxiety and dread, so Robert Sapolsky. Thanks very much for being on The Mindscape Podcast.

1:25:41.0 RS: I think, Sean, this has been a real pleasure.

[music][/accordion-item][/accordion]

Brilliant!

Sean, Robert, thank-you both so much

Having a sense of this knowledge collectively could only narrow the chasm of mental anguish between the processes of Rational v. Rationalized

Magisterial

What it is to be interdisciplinary

Love & Wishes

John

Thanks for having Robert Sapolsky on your podcast. I’ve been hoping for this for a long time. I think “Behave” has left more of an impression on me that most books I’ve read, and it’s always a pleasure to hear him speak.

Yet another excellent episode from a consistently excellent podcast.

Prof. Sapolsky should be a member of President Biden’s Cabinet. All policy-making governmental bodies should have to consult with him as policies are developed. There should be a “Federal Department of Behavioral Development” to bring awareness of our cognitive pitfalls to the population at large, and he should design it.