This episode is published on November 2, 2020, the day before an historic election in the United States. An election that comes amidst growing worries about the future of democratic governance, as well as explicit claims that democracy is intrinsically unfair, inefficient, or ill-suited to the modern world. What better time to take a step back and think about the foundations of democracy? Cornel West is a well-known philosopher and public intellectual who has written extensively about race and class in America. He is also deeply interested in democracy, both in theory and in practice. We talk about what makes democracy worth fighting for, the different traditions that inform it, and the kinds of engagement it demands of its citizens.

Support Mindscape on Patreon.

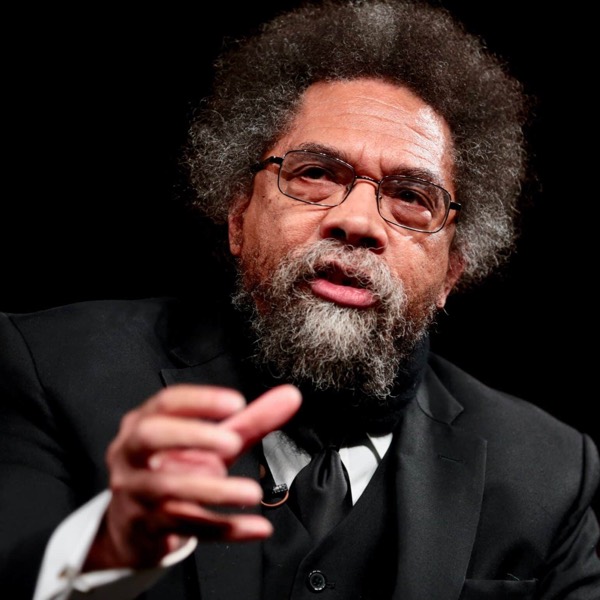

Cornel West received his Ph.D. in philosophy from Princeton University. He is currently Professor of the Practice of Public Philosophy at Harvard University as well as Professor Emeritus at Princeton. He is the author of numerous books, including Race Matters and Democracy Matters. He is a frequent guest on the Bill Maher Show, CNN, C-Span, and Democracy Now, appeared in the Matrix trilogy, and has produced three spoken-word albums. He is the co-host, with Tricia Rose, of the Tight Rope podcast.

- Web site

- Harvard web page

- IndieBound author page

- Talk on Race, Democracy, and the Humanities

- Wikipedia

[accordion clicktoclose=”true”][accordion-item tag=”p” state=closed title=”Click to Show Episode Transcript”]Click above to close.

0:00:00 Sean Carroll: Hello, everyone, and welcome to the Mindscape podcast. I’m your host, Sean Carroll. A few months ago, I put up a poll on Twitter. I just simply said, “How would you prefer to be ruled?” And the two choices were according to popular will, and by one wise and good person. The results came in. They were a little bit surprising to me. It was almost two-thirds of the respondents said by one wise and good person as opposed to the popular will. I pointed out that basically you’re voting for dictatorship over democracy, and when I pointed that out, people were outraged. They said, “Well, you worded your poll very badly. You didn’t say dictatorship versus democracy, you said by a wise and good person. You made the dictatorship sound attractive.” That’s the point. The point is that when dictatorship comes, it will sound attractive. People do not just campaign on a pro-dictatorship platform. They say, “I’m the one person who is wise and good who will fix everything.” This kind of attitude is extremely attractive.

0:01:00 SC: There are reasons why democracies fail. I know plenty of people who I consider very, very smart, people whose judgment I would generally trust, and they seem to think that it would be good if one really good person was in charge of everything. Depends on who the person is, of course, right? For some, it’s Bill Gates or Elon Musk or Warren Buffett or Barack Obama or Donald Trump or Bernie Sanders or Oprah Winfrey. People can disagree who the person is, but the idea that, “Ooh, we’re in such a mess, if just one person could come in and clean everything up,” that’s the temptation that leads to democracies failing. Democracy sounds good when you first hear about it, and you say, “Oh, yes, I get a voice in how the country is run? That sounds great, I’m in favor of democracy.” But at some point, you realize, “Wait a minute, you mean all those other chuckleheads also get a voice in how the country is run? Those people are idiots. I don’t want those people to be in charge, I want someone who I actually trust to be in charge.”

0:02:02 SC: But that’s the bargain you make in democracy, right? If you actually think that democracy is a good idea, you don’t simply say, “Well, I want a voice.” You say, “I would like the actual interests of the people as expressed by the people themselves to basically be how we choose how the government is run.” Now, of course, there are details, we don’t actually have plebiscites or ballot initiatives for every single issue in the country in a place like the United States. We have a republic, but a republic is not something that is different than a democracy. A republic can be democratic, as ours is. The people vote for their representatives, and then those representatives go off and run the country. If you really buy into the democratic ideal, you’re saying that you have an obligation to try to convince other people, through the force of reason or persuasion, by whatever means, to be on your side. That’s a difficult thing. That’s something where it can be very, very annoying when you just want to say, “Look, I’m right, let’s get it done.”

0:03:04 SC: But in my personal view, democracy is worth it. Yes, the populist, the popular will, will not always make the right choice. Yes, we need to protect the rights of minorities so that the majority cannot simply trample over them. Of course there’s all sorts of footnotes here, but the idea of democracy is incredibly valuable, incredibly important. So today we have a special Election Day episode of the Mindscape podcast. I’m releasing this the day before the 2020 elections here in the United States. The United States is still, despite our recent failures, an important country worldwide, so hopefully this will be of interest to everybody.

0:03:41 SC: And our special guest is Dr. Cornel West, probably needs no introduction. Cornel West is a very well-known philosopher, one of the, probably one of the most well-known public philosophers in the United States in the world today. He’s a professor at Harvard and he’s written about many, many issues. He sort of came into the public eye most obviously with a little book called Race Matters. He’s also done things like recorded a rap album and been a cameo appearance in The Matrix trilogy, so that’s a life well lived as far as I’m concerned. But he had a little follow-up to Race Matters called Democracy Matters, and the idea of democracy, the importance of democracy, and how it works has been a motivating interest and concern of his throughout his career. One of the interesting things about Cornel West is that clearly politically, he’s very far on the left, but he has been an absolute champion and a sincere one and a consistent one for talking across the aisle, for building coalitions, for using the force of reason to try to convince people that we should work in certain ways and listening to them, right. As we’ve said before in the podcast, listening is as important as talking when it comes to communication both ways.

0:04:54 SC: So I think this is an important discussion to have. Why is democracy so great? Is democracy so great? How can we make it better? What are the failures that we have and how can we fix them? If nothing else, I hope to inspire anyone who’s on the fence to go out and vote, whoever you vote for. I’m someone who thinks that the participation in the democratic process is just incredibly, incredibly important. I know a lot of people, especially big fans of what is sometimes called a science podcast, think that politics is annoying and should get out of the way, we should not be talking about politics, we should talk about the laws of nature and eternal truths and all that.

0:05:34 SC: But politics is important. Sorry, I have to disagree with you there. Politics is how we choose to organize our society. It’s one of the most important things we can imagine. And I think that the reason why a lot of people find it annoying is, as soon as you start talking about it, people get emotional. People’s intellectual effort goes down and their visceral reaction goes up, and so it can indeed be very, very tiring to have political conversations. But that does not decrease our obligation to do so, especially in a democracy, especially when the ultimate decisions about how to run the polity is in the hands of we, the people. So it’s in your hands. Go out there and vote, if you’re in the US. Go out there and vote at other times in other places if you’re elsewhere. And let’s go.

[music]

0:06:42 SC: Cornel West, welcome to the Mindscape podcast.

0:06:44 Cornel West: Well, I want to thank you for having me, though, and I appreciate the work you do, and what a force for good you are in this complicated discourse of science and culture and politics and meaning and purpose, I deeply appreciate it, my brother.

0:07:00 SC: Maybe I should just let you keep on in that vein for the next hour, this is making me feel really good. I don’t want to ruin it.

[laughter]

0:07:09 SC: But no, thank you very much, and also I want to, before I forget, send out thanks to Suzi Jamil of the Think Ink organization in Australia, she has organized speaking events for both of us, and she was the connection that brought us together, so thanks to her. Everyone who’s in that down under part of the world should check out their events.

0:07:26 CW: Absolutely, she’s wonderful.

0:07:28 SC: And when we’re… We’re recording this a couple of weeks early, but this podcast is going to be published the day before Election Day here in the United States. They just had their election day down under in New Zealand, it was kind of fun, and one way or the other, Election Day 2020 is going to be historic, right? It’s fraught for people on all the different sides, so I thought it would be fun to talk about democracy, you’ve written a lot about democracy, and it’s one of those topics where we kinda take certain attitudes towards it for granted, but events of recent years have made us sit back and contemplate what it’s all about in a slightly more careful way. So let me put it to you this way, what’s so great about democracy? What would your sales pitch be to someone who is skeptical that it was the best way to organize a society?

0:08:22 CW: Well, I would say that democracy is fundamentally founded on a certain suspicion of dogma in opposition to domination, and so I would begin by saying, well, if someone is interested in the Socratic legacy of Athens and fundamentally believes in relentless questioning and self-questioning, and believes that one ought to be fallible and humble in one’s orientation toward the world, acknowledging that no one has a monopoly on truth, then you begin to set up mechanisms of answerability. So that with Socrates dialogue is grounded in answerability, I put forward a claim, there’s a counter-claim, there’s evidence, there’s counter evidence, argument and counter-argument. And at the same time, the prophetic legacy of Jerusalem, which has to do not just with that love of wisdom, grounded in answerability and fallibility, but a deep love of the neighbor that’s tied to justice, and justice here is not just a norm that regulates various social institutions, but it is a force in one’s education and cultivation, that has to do with trying to unleash empathy, and unleash compassion, unleash benevolence.

0:09:38 CW: And so when you look at those two grand pillars of the Socratic and the prophetic, and the opposition to dogma and domination, you end up with a way of life and mode of governance that is grounded on fallibility and accountability, grounded on a certain kind of concern for the other, a certain concern for neighbor in a democratic setting, it would be citizen, I believe, of course, in the larger international and global views, so that we’re concerned with citizens, of a variety of different nation state. But those are the two pillars, and I think, my dear brother, that at the expense of sounding a bit whiggish and thinking that somehow the evolution leads toward us, I think that those two pillars are some of the best, if not the best forces that we as a species have been able to dish out to each other, and to the world, and to the cosmos, I really do.

0:10:39 SC: It’s very interesting that humility is the first thing, fallibility that you think of, because as a scientist, I’m very used to hearing that science is not a democracy, people don’t vote, there’s the truth that is out there, but the practice of science is very much founded on the idea of fallibility, that none of us is the emperor of science, anyone can overthrow things. And I do see that’s also a spirit that energizes democracy.

0:11:06 CW: You are absolutely right. You remember the great John Dewey and the Gifford Lectures of 1929, The Quest for Certainty, where he makes a distinction between scientific method and scientific temperament. And he understands the way in which dogma can surreptitiously operate within the scientific community itself, so you become too tied to one method, so the method itself becomes a form of idolatry. But the scientific temper cuts much deeper, and that’s the Socratic energy, that’s where you acknowledge a prevailing paradigm in place. You’re thinking of Thomas Kuhn’s great text of 1962, The Structure of Scientific Revolution. Certain paradigm frameworks, certain theoretical orientations, or schools of thought themselves can become blind spots, can become forms of idolatry. But the scientific temper is always critical of any kind of dogmatism even within the scientific community. And that’s why the science itself at that deep temperamental level, that deep Socratic and Deweyan level, is one of the best things that we as a species have been able to create and forge and pass on from one generation to the next.

0:12:22 CW: But at the same time, we also recognize that there are dimensions of being human, that even the great forces and achievements of science cannot take us from. And here, I would go with Percy Shelley. When Shelley says, “Poets and philosophers are the unacknowledged legislators of the world,” he says that in the Philosophical View Of Reform, an earlier text. It’s is more famously put forth in A Defence Poetry, where he only talks about poets, but he had poets and philosophers in A Philosophical View of Reform, the first version of that. And what he’s saying is is that science itself, indispensable, science itself, unavoidable, crucial, one of the most, if not… Well, I would say, one of the most fundamental armors that we have as a species, still doesn’t take us far enough. We need to have visions that are tied to what it means to be human beings who have fears, anxieties and insecurities on our way to being the culinary delight of terrestrial worms. Therefore, issues of death and dread and despair and disappointment and betrayal have to be also attended to.

0:13:38 CW: And even the scientific temper gives us a certain kind of fallible orientation, but it doesn’t give us the kinds of stories and narratives and symbols and metaphors that we need in order to try to live lives of meaning and significance. And so the two are so intertwined. In some ways, I’m just building on your notion of poetic naturalism, though, brother.

0:14:02 SC: Very good. [chuckle]

0:14:03 CW: You’re already there. You’re already there in terms of what I’m talking about. But you can see how it resonates with Dewey’s version of naturalism or Jeff Stout’s wonderful version of naturalism is, my dear brother, one of the great naturalists alive right now. Or George Santayana, who was who’s one of the towering figures, who was able to wed his form of naturalism with an unbelievable love of poetry and structures of meaning, and structures of feeling. I was blessed to actually have a teacher named Nelson Goodman…

0:14:41 SC: Oh, of course.

0:14:42 CW: Who is one of the great philosophic geniuses. He was part of the second golden age at Harvard, in the philosophy department, that first golden age being, of course, with James and Josiah Royce and Santayana and Münsterberg. But that second golden age was when you were there, brother. Rawls and Nozick, and Cavell and Putnam, but also Goodman. And Nelson Goodman oftentimes is overlooked because of those other philosophic geniuses, but he was one himself. And as you recall, his particular form of naturalism was a pluralistic one, alternative descriptions, ways of world-making, concerned about acknowledging what our ends and aims are when we create the different kinds of conceptions of the world. So that, and his dissertation that was such a devastating indictment of Rudolf Carnap’s logical construction of the world where the Aufbau… There’s a pluralism that’s inherent here that needs to be teased out. And of course, Nelson Goodman was also himself an artist, head of an art gallery, but deeply concerned about a scientific temper at that deep level, not just scientific method. And I see some deep similarities between your notion of poetic naturalism and those figures, but what would you say, my brother?

0:16:13 SC: Oh, yeah. No. Absolutely, in all sorts of ways. One of my cherished memories of being a grad student at Harvard was taking classes with John Rawls and Robert Nozick, and I nevertheless regret that I didn’t sit in on Putnam or Goodman or so many other people. And it’s… I’ve fundamentally… This is getting way off track for democracy but that’s okay. It’s a conversation.

0:16:36 CW: Oh, no. I think it’s connected in terms of the geist, the spirit of democracy.

0:16:40 SC: Yes, I do, I do think it is, and it’s the pluralistic aspect that connects it. The fact that you need not just different political opinions, but ideas from all sorts of corners of the intellectual stratosphere coming in to enrich our lives as citizens and people.

0:16:56 CW: Absolutely. The anthem of Black people is lift every voice, it’s not lift every echo. So you don’t want an extension of an echo chamber, you just don’t want an expression of some kind of tribal consensus. But you want people to think for themselves critically, just like they’re gonna love for themselves intensely. And by lifting every voice, it cannot but lead toward the kind of pluralism at the high epistemic level that Nelson Goodman and yourself and Dewey and Santayana and others were talking about. But it also allows for the kind of overlap between the poetic and the scientific without any kind of narrow reductionism. You’re not gonna reduce poetry to science, or science to poetry. You’re not gonna slide down a slippery slope to any kind of sophomoric epistemic relativism.

0:17:51 CW: But you are gonna have a contextualism and recognizing the ways in which our different expressions, our different attempts to engage in world-making have to be able to enter public space without humiliation and be given a hearing based on answerability, based on mechanisms of accountability. You remember that wonderful moment in Walt Whitman’s Democratic Vistas where he says, “Well, democracy itself is untried.” Why? Because for the most part, we don’t have conditions under which people are willing to enter public space without humiliation and engage in an intense, robust, and uninhibited discussion. And we would say inquiry in the scientific context. But those are the kinds of intellectual resources that we need as democracy itself is undergoing such massive decay and deterioration. We need all the courage in the world and of course, you got those [0:18:56] ____ sitting in the corner.

[laughter]

0:18:58 CW: Those guests who said, now I told you that you’re expecting too much out of this species. They really don’t have the orientation that’s required to be Socratic and prophetic. You’re putting too much on their backs. The Grand Inquisitor is going to come in and give them the authority and use the mystery and miracle to manipulate them because they’d rather follow a Pied Piper than they would think for themselves. They’d rather defer uncritically to authority than be Socrates. Of course, most people not crazy about him like anyway. “No, that’s too much for me.”

0:19:39 SC: But that’s what I want to get into, because you’re bringing us right up to what I think is this huge challenge that people often paper over a little bit, which is that democracy is incredibly demanding of us.

0:19:51 CW: Absolutely.

0:19:52 SC: I just did a podcast with Teresa Bejan, who is a political theorist at Oxford who’s written about civility, and her favorite character is Roger Williams in Rhode Island, and how his model of discourse was not just let people speak, but there is a positive duty to listen to them no matter how much you might disagree. And I think that democracy sounds good when it sounds like I get a voice, but people will catch on to the fact that it means all those wrong people get a voice too, and they become a little bit more skeptical.

0:20:25 CW: Very true. You are absolutely right, she’s absolutely right. But again, you can see the connection to jazz here, that you can’t be a jazz woman or a jazz man without finding your voice and moving from echo to voice. We all begin with imitation and emulation and have to move toward becoming creations and becoming real originals rather than just copies of copies. But at the same time, you can’t find your voice without listening to other voices. Voices of the dead, because the voices of the dead, of course, is full of so much wisdom, tremendous blood, sweat, and tears, and struggle, and voices of the dead in a variety of different civilizations and cultures, cut across skin pigmentation and gender and sexual orientation and so forth and so on. But at the same time, you have to cultivate a faculty of receptivity, a faculty of listening, and yet even as you listen, you’ve got to critically filter what you hear, because everything you hear is not worthy of acceptance. And that’s where, again, answerability sits at the center.

0:21:38 CW: Louis Armstrong did not like Charlie Parker. Now, Louis Armstrong is the genius of geniuses. He was wrong, he was wrong as two left shoes. And the same way with Einstein, vis-à-vis quantum mechanics. Well, God played dice with the universe, okay, Albert, let’s see, let’s see, let’s see if the evidence says… Maybe he read too much Spinoza and he’s just holding on too much Spinoza, whatever’s leading towards your blind spot. But we know Einstein to be the great Einstein that he was, he just didn’t have a monopoly on truth either.

0:22:15 SC: No one does. And it’s funny, because…

0:22:17 CW: No, that’s right.

0:22:18 SC: One of my favorite of my early episodes of this podcast was with Wynton Marsalis, and I kept wanting to ask him about music, but he wanted to talk about America. And I see, I think you finally answered the question for me in my mind about what the connection is there between jazz, or group performance, it could be basketball, it doesn’t need to be jazz, and democracy, that bottom-up teamwork, sacrifice in the right place, accept other people’s roles kinds of things. And you have a name for it… And you wrote a book Democracy Matters where you talk about the tragicomic tradition that goes into democracy, which is a little bit… Which is not something I read in a lot of political theory books, so why don’t you expand on that a little bit?

0:23:04 CW: Yeah, no, it’s true, it’s true. Well, I was blessed, like you, to spend a lot of good time with magnificent teachers, those who we’ve mentioned before, the Nozicks and Rawlses and Putnams and Gutmanns and Quines and Roderick Firths, and Martha Nussbaum’s and others. But at Princeton I was blessed to study with the greatest political theorist of democracy of the 20th century, his name was Sheldon S. Wolin. And his notion of fugitive democracy, that democracy is not so much an institutional arrangement, but rather it is an episodic and fugitive expression of the visions and demands of those who are dominated. And for the most part, they will be crushed, for the most part, they will be marginalized, for the most part, they will be devalued and dishonored. But their legacy will be one in which people will be able to remember their vision. It’s like Shelley and calling philosophical view of reform way back in the 18-teens, he’s calling for universal suffrage and women’s suffrage and what have you… Well, they wouldn’t get that until the 20th century. Well, he was ahead of his time. He’s not alone, women and others were doing the same thing, of course his companion Mary was even further along than he was in that regard.

0:24:35 CW: But you see folk who are trying to accent certain values and visions and virtues that tend to get snuffed out, that tend to get pushed aside, and so there’s a tragicomic quality to that, ’cause tragicomedy is diffusion of tragedy, and tragedy, of course, is the exercise of high levels of courage and freedom against limits, against what Plato called anongay, against constraints. And when you hit those constraints, you go under, the way Antigone does or the way Hamlet would or what have you. But the comic is a little different, because the comic is located in the everyday lives of people. This quotidian, the tragic historically was reserved only to those well-to-do upper classes. Not ruling-class figures, Hamlet was a prince.

0:25:34 CW: And the Greek characters tend to come from various famous families and so on, whereas the comic was always confined to just everyday people, but when you get a fusion of the tragic and the comic, then you find some of the richest exercises of courage and freedom among those who I still would call everyday people, and that’s where the democratic project is, because the democratic project is about everyday people cultivating and educating themselves to such a point that they can ascend to moral and spiritual excellence and raise their voices to shape their destiny, their collective destiny, with mechanisms of accountability. It could be executive and judicial and legislative branches trying to keep each other accountable, or it could be periodic elections, it could be town hall meetings where you have tremendous conversations going on, or it could be workers councils where you democratize the workplace. The kind of thing that so many council communists and council socialists and even distributed to it’s like Chesterton of more conservative twists, but still very much wedded to ordinary people’s voices being heard in that way.

0:26:55 CW: And so the tragicomic is really the acknowledgement of the fragility, of the fugitivity in the Wolin sense, democracy as fugitive. Usually it hardly has a chance to sustain itself because the powers-that-be, the oligarchs, the plutocrats… And they come in all different colors, they come in all different cultures, and they come in all different social systems. The communist systems have their own oligarchs and plutocrats with the political parties that don’t have accountability to the workers. Capitalism’s got the monopolies and the oligopolies, and Wall Street, it has very limited accountability vis-a-vis ordinary people and their connection with even the elected politicians. We saw it, for example, in 2008, when Wall Street got bailed out and received trillions of dollars and homeowners received hardly anything at all. Not one Wall Street executive went to jail after all of that insider trading, market manipulation, fraudulent activity, predatory lending and so forth.

0:27:58 CW: But it just shows, under capitalism or socialism or communism, you still have your oligarchs and plutocrats at the top. Unaccountability meets at the top, and therefore any genuine democracy has got to be concerned about the concentration of power in the private and the public sphere. And therefore, it’s a tragicomic affair because it tends not to be able to sustain itself for too long, though, brother, so it has a certain grimness too, but it’s like the blues. The blues are a tragicomic thing. The blues is the music where democracy hits through political regimes, you see, that it’s in the minor key, it’s dissonant. And Duke Ellington says that dissonance is a way of life for blues people. Dissonance. You stand in the minor key, you and Beethoven, C minor. It’s a little different than regular C, as you know. [chuckle] You can bring in some of those black notes, brother, on the piano.

0:29:02 SC: Well, this is very important, because a naïve reading could sort of dismiss the idea that blues and jazz have anything to do with democracy, which is politics and government, but there is more to democracy than you show up and vote, right.

0:29:19 CW: That’s right.

0:29:19 SC: There’s an ongoing conversation. There are expressions of opinion outside of the voting booth, and they include explicit protests and social movements, but they also include the artistic side of things.

0:29:34 CW: Absolutely. No, we would just turn people to read John Dewey’s great classic of 1916, Democracy and Education: “Democracy is a way of life, it’s a mode of existence, it carries its own kinds of spirit, its own kind of sensibilities and sentiments that inform the institutions.” And if the democratic institutions are no longer informed by a democratic spirit, then they get manipulated and dominated and colonized by oligarchs who are operating, and they can call it democracy all you want, but it’s not… It has little to do with democratic practice.

0:30:14 CW: And the same would be true, and as you said, you noted before, in certain cultural arenas, you can have symbolic democratic action, where people are raising their voices, listening, receiving other voices and wrestling with the kind of civilized, antagonistic cooperation and creativity that we associate with democracies. But it would be a jazz orchestra, for example, and it doesn’t have any kind of institutional translation in the larger society. That larger society can be apartheid America, which it was up until 1965, and yet jazz was still flourishing. But I would say the same thing about the best of the scientific community. This is Henry Putnam’s powerful point in his readings of Dewey… I was blessed to teach with him the last class that he taught at Harvard, here in Philosophy Department, on neo-pragmatism, that for him, the scientific community at its best had a democratic spirit. But you see, a democratic spirit still has certain elitist aspects to it because any of us who lift our voices know that, you know, you and I, we’re not gonna sing like Johnny Hartman or Frank Sinatra, or Bing Crosby, I don’t want to be premature about your vocal…

[chuckle]

0:31:44 SC: No, no, no you’re very accurate about it.

0:31:46 CW: Your vocal talent or anything, but I’m speaking for myself. You know what I mean? So that there’s going to be certain hierarchies in terms of sheer cultivated talent and certain cultivated gifts, but as long as there’s mechanisms of accountability and answerability and people are choosing which particular kinds of pursuits they have, then there’s going to be a certain kind of well warranted elitism that has nothing to do with color, or gender, or where you were born, and so forth and so on, it has to do with the choices you make and the gifts that you cultivate, but unfortunately, people think of elitism solely tied to the vicious kinds of racisms and sexisms and chauvinisms and tribalisms that have been so dominant in the history of our species.

0:32:37 SC: You make the point very clearly and correctly about the concentration of power, which can seem paradoxical in a democracy, if you just let everyone vote how can it be that the same families keep getting elected to the presidency and so forth, but so… Practically speaking, what do we do about that, what is both sort of the bottom-up the duty of the citizens and also the top-down way we organize the system to sort of really let the democratic ideal manifest itself in our actual democracy, not just in the ideals?

0:33:10 CW: Well, a lot of it has to do with our forms of education and cultivation, because you see, when you’re talking about elections you have to be as concerned about the background conditions of the elections, because we know to be a politician already means you need big money, where’s the money gonna come from? What is gonna be the relation of big business providing this portion amount of money, this is why my dear brother Bernie Sanders was a so very important unprecedented politician at the presidential candidacy level saying, “I’m not gonna take one penny from Wall Street corporate elites, the power elites at all, everything’s coming from ordinary people.” That was… That’s unprecedented, because for as long as we can remember, American politics has been deeply shaped by big money, there’s no doubt about that, and if big money is one of the fundamental brooks of fire you must pass in order to be a politician, then you already excluded a whole wave of people not just because of their wherewithal but also because of their politics.

0:34:18 CW: If they have a critique of Wall Street the way, let’s say, brother Bernie Sanders did, then he’s not gonna get a penny from them anyway, [chuckle] so that someone like him hardly had a chance. The great Norman Thomas, who was one of my heroes, a Princeton grad in 1905 and Union Seminary in 1911 and ran for socialist… Had a socialist party for almost 50 years, ran against FDR. John Dewey supported him three times. John Dewey is the greatest public philosopher in the history of the American empire and he’s behind Norman Thomas. Well, Bernie Sanders is part of the tradition of Norman Thomas and Eugene Debs and company of Martin Luther King, Jr., when he got the call for the Nobel Prize he said, “Don’t give it to me, give it to Norman Thomas.” [chuckle] They said, Norman who?

[chuckle]

0:35:11 CW: This is in my own book, The Radical King, and when I published King’s essay, the bravest man I ever met, everybody say, “Ooh, Martin Luther King knows somebody who’s braver than him?” He said, “Oh, shoot, I fall short. The bravest man I ever met was Norman Thomas.” Now, how was this black man who’s known to be the bravest and one of the greatest visionary freedom fighters of the 20th century talking about this vanilla brother, Norman Thomas, Phi Beta Kappa of Princeton. What is going on? Well, like Bernie Sanders in the 1920s, ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, he died in ’68, same year that Martin did, but he was much older than Martin, of course, that he manifest this unbelievable attempt to keep track of the background conditions of US elections, not just the elections themselves. And the background conditions meant he had to have critiques of the corporate elite, he had to have critiques of the big money donors, he had to have critiques of those the Occupy movement called the 1%, and he got in a lot of trouble.

[chuckle]

0:36:21 CW: He went to jail so many times you couldn’t even count. Couldn’t even count. But we need exemplars. This is the important point I’m making, you know, brother, that you have to have exemplary figures, movements, institutions. You got to have… People have to be able to see… You remember that line in Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason? I think it’s about page 177 in the Kemp Smith translation, he says, Examples are the go-cart of judgment. Examples are the go-cart of judgment, the judgments that we make, practical judgments that we make, what Aristotle would call phronesis, the practical wisdoms that we exercise are deeply shaped by the examples that we have in our minds. And there’s much to… And this is Kant. If anybody’s obsessed with rules…

0:37:19 SC: Yeah… [chuckle]

0:37:20 CW: It’s gonna be Kant.

0:37:21 SC: He’s a little stuffy.

[chuckle]

0:37:21 CW: He may have a Wittgensteinian moment there when he says, well, you can’t appeal to a rule to teach you how to apply a rule, so that…

0:37:27 SC: You know, I think you…

0:37:30 CW: You reach a point where you have to intervene with some bedrock wisdom that allows us to help get rules following off the ground.

0:37:40 SC: That’s right, and the Bernie Sanders example is a very interesting one to consider because the Democratic primary this year… For those of you who are listening to this podcast 100 years from now, we had a primary election to choose the nominee and Joe Biden, who was sort of the least objectionable candidate in many ways, won and one of the challenges of democracy is at some point, you have to say, okay, my favorite didn’t win, I’m gonna support the least bad person out there. And that’s a huge challenge to a lot of people, it seems that in this particular election, people are putting aside their objections and moving in that direction. But what kind of moral burden does it put on you to say that we have to accept the lesser of two evils?

0:38:28 CW: Well, I’m not sure I would use the word except, my brother, because I mean, I’m pushing for people to vote for Biden. But I don’t endorse him, I don’t accept him, I’m not gonna lie about him, I’m not gonna argue that somehow he’s some grand progressive that expresses my own values and sense of being in the world. So that the crucial thing is not to fall into the kind of circus-like propaganda that lead people to just tell lies about political candidates in order to convince people to vote for them. That for me, if you have a calling that is Socratic and prophetic, then it means exactly what you said. You tell people honestly, you respect them enough to be candid with them and simply say, “I believe brother Trump is a neo-fascist gangster who could bring down the curtain on the democratic experiment. Therefore, we must have an anti-fascist coalition. In that anti-fascist coalition, there will be neo-liberals like brother Biden and sister Harris and brother Obama, and the Clintons and others who are not in any way, for me, friends of poor people or even friends of working people, but they’re part of our coalition because they’re not fascists.”

0:40:00 CW: And what Trump represents is calling into question the very possibility of any kind of democracy. That’s what fascism does. Whereas with Biden, as a neo-liberal, he’s too tied to Wall Street, he’s too tied to Pentagon militarism. He’s too tied to surveillance states. There’s a lot of things I’m critical of. But he’s part of an anti-fascist coalition, and therefore a vote for him is an attempt to keep alive some possibility of democracy. And you can see it goes back to Sheldon Wolin’s rich notion of fugitive democracy, because democracy itself is just such a fragile thing. And that’s why [0:40:40] ____ long and that’s why its history is really not a pervasive one in terms of the history of the species. And we can talk about the last 150, 200 years and see some democratic stirrings, but generally speaking, most of the civilizations, most of the political regimes, no matter where they are, no matter where they are, Asia, Africa, Latin America, even I know our indigenous brothers and sisters would say, “Well, we had democratic forms that were at work before the Europeans got here.”

0:41:10 SC: Yeah.

0:41:10 CW: Yes, Iroquois Confederation was real, the confederation was very real and so forth, but they also had some deep hierarchies that full-fledged democratic practices would call into question. And so we just have to acknowledge the degree to which as a species, we’re just so tied to egoism and tribalism. It’s the point that EO Wilson makes in one of his career-encapsulating and summarizing books, The Meaning of Existence. When I read that, “Let’s see what this grand sociobiologist has to say after studying ants and other phenomena so well.” And he said, “Look, it really comes down to trying to transcend the pervasive egotism and tribalism of the species in light of the fears and anxieties that we have.” He’s absolutely right. And myself as a Christian, I’ve got particular stories that mean much to him. He’s an ex-Christian. He comes out of an evangelical family, as you know, and made his own breaks toward certain form of secular ways of engaging the world. But similar kinds of concerns are trying to get beyond the kind of egotism and tribalism that democracies attempt to get us to do. That’s what the Greeks were doing.

0:42:24 CW: You used to have a tribal identity, now you’re gonna be tied to this demi, and this demi is gonna be an identity that transcends your tribe, that forces you to have an allegiance to something public that’s bigger than your tribe. And that’s what Cleisthenes was trying to do, and they made a go of it. They still had slavery, they still had domestic households, ugly forms of domination were still at work. But they also had the stirrings of a very rich democratic regime. And we don’t know of a democracy that’s not founded in some way on a form of barbarism, on various structures of domination. So most of them are imperial democracies, they’re patriarchal democracies. In the modern world there’s often been racist democracies, but democracy has the capacity to speak to racist forms of domination, gender-based forms of domination, unleashing self-determination across the board.

0:43:32 SC: Are you someone who thinks that there is something in the democratic ideal that is self-correcting? We all think of the Declaration of Independence and all men are created equal. And clearly, they didn’t even believe that when they wrote it, but had they written all white property-holding men are created equal, we might have had a very different history for this country. Somehow they aspired to something that was better than they were, which is kind of miraculous, but probably has a down-to-earth explanation.

0:44:07 CW: No, I think you’re right. Here, I could be wrong, but I’m fairly convinced that when you fully unleash what I’m calling the Socratic energy of the relentless question, and the great Alfred North Whitehead, you remember in his book, Adventures Of Ideas, he says that the noble discontent released by Socrates on the one hand, what he called Hebrew prophets, another moment he calls it critical discontent. But this unleashing of a critical consciousness that leads toward a serious and candid examination of the world. Now, in the social world that means you’re going to come to terms with a lot of suffering and misery.

0:45:05 CW: But you also have to come to terms with the forms of resistance and the forms of critique. In the natural world, that means you’re gonna have to recognize that there’s mysteries beyond your theoretical frameworks and paradigms, but that should not dampen your spirit in trying to understand, explain and predict what’s going on here and in the other parts of the cosmos, on Earth and other parts of the cosmos. That to me is just so rich and something magnificent about it. It has a majesty, actually.

0:45:43 SC: I’d be out of a job if we were not still full of mysteries that we didn’t have solved yet. So I’m very happy about that.

0:45:49 CW: That’s right. Absolutely.

0:45:52 SC: The more we discuss this… I don’t want to say it’s a downer, but it highlights how much is being asked of the people who participate in a democracy. You mentioned the idea of you don’t need to support someone but you can still be part of their coalition. You can keep up the criticism of them, hold their feet to the fire and yet vote for them at the same time. And that’s gonna be hard for some people to keep in their mind simultaneously. And also you mentioned exemplars, you mentioned Norman Thomas, Bernie Sanders, people who you’re gonna look up to and be inspired by, and in the same vein we can’t be hero-worshipping these people.

0:46:33 CW: That’s right.

0:46:34 SC: We gotta be ready to hold their feet to the fire and say, like, “No. Look, man, I’m on your side almost always but here you’ve gone astray.” And again, it’s a little bit askew vis-à-vis the human nature. We like to make things black and white and democracy is a constant balance between these different forces, and we have to live in-between.

0:46:55 CW: Well, here takes it right back to jazz again, now, brother, which is the notion of improvisation. You have to be able to be flexible and fluid and protean enough to be able to shift and move and adapt yourself. Now, there’s a real sense in which, you know, coming out of Darwin’s path-breaking work that one of the distinctive features of our species is precisely its adaptability. Precisely its adaptability. And so in the historical context in our social worlds, we have to be improvisational and adaptable. But improvisational is not just opportunist, you have to have certain kinds of disciplines that are the basis of improvisation. And by disciplines what I mean is being able to build on what has been bequeathed to you that is useful, that is insightful to build on the best that has been bequeathed to you.

0:47:58 CW: So that you get that dialectic between innovation and tradition, between creativity and antecedent prizes. Whitehead used to say nothing novel is wholly novel and Edmund Burke would add, of course, that nothing old is wholly obsolete, that we’re all locked into our various traditions to build on. And so when it comes to citizens saying, “Okay, I’ve gotta make a choice between let’s say dealing with Trump who I’m over against but not crazy about Biden.” And you say, well, there’s coalitions, well there’s coming together, there’s forms of relating to one another that acknowledge the difference but still acknowledge that together we’re able to achieve a certain end. It’s like the United States creating a coalition with the Soviet Union to the crush a gangster named Hitler. Now, you know all the anti-communist propaganda that was in place in the ’30s, for good reason, Stalin was a gangster. He was a thug.

0:49:05 CW: But without Stalin’s Army and the US Army and of course the Russians lost about 20 million in the war. We lost about 400,000 in the war. So you know who bore most of the price in that way. But without the communists and the capitalists, without Russians and the United States coming together, they would never have crushed Hitler. Well, you see, that’s what it is to be improvisational. You had to adapt. You don’t have to tell lies about Stalin to say all of a sudden he’s my ally and he’s got a wonderful social system and now he’s crushing Jewish brothers and sisters. He’s killing the kulaks. He’s killing his close friends and so forth and so on. Now, he’s also supporting some liberation movements around the world, which was worth noting, but he’s still a gangster but we need his alliance. Or we must create an alliance with him. And people do this all the time when they’re really honest with themselves. You know what I mean?

0:50:00 SC: Yeah. I do. But I do wonder, we were talking about like 30 years ago and when I was a grad student at Harvard and one of the things that happened during my tenure there was the Berlin Wall came down. I mean, the Cold War ended. If it was gonna end at any one moment, you might pick that moment. And there was this feeling that history had more or less entered a new equilibrium phase, democracy would be everywhere and then we’d all have McDonald’s on every… In every country. And it hasn’t quite worked out that way. Now, we’re worried that in the Western hemisphere democracy has lost some steam, that people are more susceptible to saying, well, the government doesn’t listen to me. I’d rather just have a guy in there who is on my side. Do you think that there’s some energy that has gone out of democracy and is there anything we can do to bring it back?

0:50:51 CW: Well, I do think we have some energy, but going back to that moment that we think of Francis Fukuyama’s highly influential text The End of History. We just had him in our seminar that I teach with the one and only Roberto Mangabeira Unger at the law school, and of course he’s moved now. He was leaning toward Bernie Sanders and he was deeply conservative in those days. But he was thinking that maybe in fact with the worldwide hegemony of the United States and with the United States very much in the driver’s seat of the world, the world capitalist order, or the international order, as it were, that there would be this kind of homogenizing taking place. But again, blind spots, blind spots are coming back and they come back to haunt you.

0:51:43 CW: Namely, the very consensus, the very widespread agreement among the trans-Atlantic countries were too often themselves predicated on war and empire and foreign interventions. There’s a wonderful book by my dear sister, Katrina Forrester, her book, In the Shadow of Justice: Postwar Liberalism and the Remaking of Political Philosophy. It’s really a reading of John Rawls and we love John Rawls, our dear teacher and brother and so forth. But when his text was published in 1971, he was predicated on consensus and agreement, and you had to generate these norms once you reach a certain kind of coming together. But there’s no talk about the hundreds of operations in other countries, many, many interventions by the US Army in other countries. Why? Because it’s a denial of empire and there’s a disassociation of foreign policy with domestic policy.

0:52:47 CW: So, his text was all about the agreement in the metropole. Okay, okay. You have an agreement in the metropole, but there’s other people in the world, and your policies are crushing some of them, and it’s gonna come back to haunt you in this way. And, of course, domestically, what comes back to haunt the United States is not just race, it’s not just slavery and Jim Crow and Jane Crow and apartheid, but it’s also class. Their consensus was predicated on corporate influence, the disproportionate role of corporate power and sustaining that consensus over the corporate liberalism and it was also predicated on professionals playing a disproportionate role. And you know and I know only, what, 33% of our fellow citizens even go to college.

0:53:41 CW: So you and I can live in a world… When we talk about Harvard and Yale and Caltech, we get fun and wonderful people there and rich ideas and so forth. But for 65% of the folk who could read on their own and so forth, no, they’re locked into very different worlds. They don’t even go to college. Now, what happens when their suffering becomes intense, they’ll either swing to the left with Bernie or they’ll swing to the right. How come? Because they have a contempt for the neo-liberal elites, and that’s what people don’t understand about the followers of Trump. They’re not all racists. No, no, they’re not all racists, even though too many are, but they’ve been crushed by neo-liberal policies, the wealth distribution going from them to the 1%. They see the greed at the top. They see the arrogance at the top. They see the hardiness at the top. They read the New York Times, they read The Washington Post and they see the insularity and the parochialism and the in-crowd jokes and so forth and so on and they feel put down. And that populism is gonna go in one direction or another.

0:54:50 CW: It’s gonna be a left populism, it’s gonna be a right populism. And when it’s a right populism, white supremacy is gonna be the public face because that’s been one of the ways in which there’s been a consensus on the vanilla side of the country. Keep these black folk down. Keep these indigenous peoples invisible. Keep these brown folks marginal and so forth. And then, you get the worst of the country and the worst of the country we see in brother Trump himself, which is the wholesale mendacity, lying, denial, not just denial of any form of evil, not just denial of white supremacy, denial of escalating ecological catastrophe, the wholesale denial of empire, any kinds of foreign policy that’s tied to US corporate and geopolitical interests as an empire.

0:55:43 CW: And so, you end up with Peter Pan and Main Street Disneyland which are refusing to grow up. We’ve grown rich and grown powerful. But, like Peter Pan, we don’t want to grow up and then we want to be on Disneyland, on Main Street Disneyland. We want fun, we want smiles. We don’t want death. We don’t want domination. We don’t want dogma and all the things that are part and parcel of the human condition. No, we don’t want those. We want some lollipops in Main Street Disney-world. Now, all of us want that for our kids at a certain moment in their lives. Don’t get me wrong. I took my daughter there a number of times, my son too, but I’ve taught them the difference between fantasy and reality.

0:56:28 SC: So in my more idealistic moments, I have this idea that the most efficient, cost-effective way we could make the world a better place would just be to let everyone become as educated as they wanted to be. Get better public schools everywhere, college free for everybody. Do you think that’s a complete fantasy or do you think that would be a move in the right direction?

0:56:48 CW: No, I think it’s a move in the right direction. It’s just that again, we would never want to view that as a panacea, because there are forms of mis-education that go hand-in-hand with these formal institutions associated with education. It would have to be Socratic, Deweyan, prophetic, with an acknowledgement that we are going to always defend people’s right to be wrong. Here, Mill’s On Liberty, the classic of 1859, is very, very important. And this is why a certain libertarian strand has to go hand-in-hand with any democracy. Rights and liberties, precious. They’re the pre-condition of any democracy. And as long as you get people rights and liberties, there’s gonna be people who deeply disagree with you and their voice must be heard in that public space.

0:57:41 SC: That’s it. It’s a tough thing to do. To go…

0:57:43 CW: It’s hard. It’s hard.

0:57:44 SC: You said a little bit about this, but whenever people bring up Rawls, because I loved John Rawls… I tried very hard to talk to him about philosophy. I never succeeded ’cause he liked physics so much that once he found out that I was a physicist, he would always just ask me questions about cosmology and the Big Bang.

0:58:02 CW: Ah, that’s fascinating.

0:58:03 SC: But there is this sort of utopian aspect in his way of doing things, and maybe today, Habermas is someone who maybe in a more complicated, sophisticated way brings in this idea that just the force of reason can bring us to some better place. And is that too utopian? There’s so much else going on with power structures and economic worries. Do we have to be a little bit more clear acknowledging the limitations of the force of reason?

0:58:34 CW: No, I think we’ve gotta exhaust all the forces of reason we can, but it can’t be what Whitehead called one-eyed reason. You see, it can’t be that narrow kind of an instrumental reason that the Frankfurt school was critical of. It’s got to be reason in all of its various dimensions, and of course, one of the benchmarks of a highly wise person who wants to unleash all the forces of reason is to always know that reason always has its limitations too. We don’t know exactly where they are, but we know it does. And I’ll tell you about Rawls. Rawls was very complicated in this regard. He was my very, very dear friend. I spent time at his house all the time. You know who was on the picture on his wall in his office, was Abraham Lincoln?

0:59:18 SC: Oh, okay, I believe it.

0:59:19 CW: Rawls was one of the great scholars of Abraham Lincoln, because he came out of World War II, you might recall he was gonna be an Episcopal priest, and from Baltimore he goes to Princeton, he loses his faith in the war. And the problematic for Rawls was always a Hobbesian one, the war of all against all, irrationality. He had seen massive, massive suffering. Of course, he had grown up giving two of his siblings a disease that he had, they died. So he had a deeply, deeply dark conception of the human condition. So when he talked about reason, it was grounded in a deeply tragic sensibility.

1:00:00 CW: And the reason why he loved Lincoln and read so much about Lincoln, you can ask James Alan McPherson, one of the great scholars of the Civil War and Lincoln, that he and Rawls could talk for hours and hours and Rawls never wrote a word hardly about Lincoln, but he read voraciously about Lincoln because for him, Lincoln was the one figure who did have a tragic disposition, we know that… Suffered from forms of depression too, but he was trying to sustain some possibility for rational, democratic experimentation and social life in a context of massive hatred and contempt and division. And so Rawls’s problematic really is very, very dark and grim and bleak, and yet at the same time he’s got this non-ideal theory that he’s working on and he’s building from Kant, and we won’t go into all of that right now. You know that and I’m sure your listeners who have read Rawls do too.

1:01:00 CW: But it’s important to give Rawls his due in terms of this larger context, you know what I mean? And Sister Forrester does that, Katrina does that in The Shadow of Justice, she actually does, because… He’s right about the fragility of it. Wolin is a political theorist of democracy, Rawls is a political philosopher of justice. Those are not the same thing. Wolin is much more tied in the history, social movements, contestation. Rawls is at a high non-ideal, at a high normative level in talking about the ideal theory and talking about what the norms ought to be and how you go about justifying those norms. That’s a different way of engaging politics than Wolin’s.

1:01:52 SC: You mentioned the fact that… I only learned about a year ago that Rawls had planned to be an Episcopal priest before he became a philosopher, and you’ve emphasized several times already the prophetic strain that undergirds some of the ways we think about democracy. But of course, democracy is traditionally a fairly secular project. How… So you have a secular person in the conversation with you here, how do you make the sales pitch for the prophetic aspects of democracy to a secularist?

1:02:26 CW: One, we can’t downplay, as you know, the crucial role of religious folk, of Jewish folk and Catholics and Protestants, in forging a democratic project. Because, see, once you democratize and move toward the lifting of every voice… You see, I’m not sure that’s a secular project, it’s simply a democratizing project in which you recognize that there is a public space that transcends the secular and the religious. It’s a community with a variety of voices. So that even calling it secular, I know my dear brother Jeff Stout in his wonderful book on the… Dissertation on the ways in which authority is democratized, would call it secularization, but even calling it secularization for me might be tilting it a little different direction. Yeah, I think democratization is one that acknowledges the indispensability of non-religious voices, the protection of non-religious voices, and yet also the protection of religious voices.

1:03:40 SC: Right, of course.

1:03:41 CW: Also the protection of… So to me, democracy is much more of a hybrid product, it seems, than just a secular one. And that’s what gets us in trouble too, so that when you get fights between the Church versus the State, you think, “Wait a minute, people in the Church have been going at each other for a long time.”

[chuckle]

1:04:07 CW: I mean, that’s partially what the council movement within the Catholic Church was all about, trying to make sure we can head off these various internal conflicts, and then Luther comes along and boom, just lowers the hammer on it, but then Luther’s gotta deal with internal conflicts within the Lutheran Church. Will he be as authoritarian as the popes were?

1:04:28 SC: Oh, my, yes.

1:04:28 CW: Well, don’t hold your breath. You know what I mean?

1:04:30 SC: Yeah.

1:04:31 CW: So that in that sense, there’s a certain kind of democratizing impulse that I think secular voices played a very, very important role. I don’t want to downplay the role that they played, but in the end, you know and I know that there’s some secular brothers and sisters who are as dogmatic as some of our Jehovah Witnesses brothers and sisters.

1:04:54 SC: Oh, sure. Some of my best friends. Yes.

[chuckle]

1:04:57 CW: When you say, “Good God,” you’re very, very parochial, given your cosmopolitan sensibility on other issues as a secular person. What’s going on here? Well, they’re human like everybody else.

1:05:09 SC: This is a point I make in The Big Picture where I talk about poetic naturalism, that even if you’re the most atheist person in the world, when you think about the history of human thought, some of the most profound and careful and rigorous thinking and ideas about the human condition have come from within religious traditions, so I guess I’m asking if I am an atheist, but I’m open to listening to wisdom from the religious traditions, what do I have to learn about democracy from those traditions?

1:05:40 CW: One, we really go back to where we started. You learn a certain humility. You’re secular to the core, and you read Dante’s Comedy, and you see the ways in which he is in awe and humbled by all of these various voices and individuals whose own persistence even after death is humanized, that touch him, that move him, and you say to yourself, “Oh, my God, I don’t have to be Catholic, I don’t have to be Italian, I don’t have to be Florentine to resonate with his sense of sensitivity and humility. Dante, thank you very, very much.” That would be true… Well, a poem by T S Eliot or W H Auden, and then of course, Toni Morrison. Toni Morrison was Catholic. A lot of people don’t talk about her Catholicism. She went to Mass regularly, and she’d had a deeply Catholic sensibility, and you can imagine so many of our beloved feminists and womanists are secular to the core. They don’t talk too much about her Catholicism, though. You see they appropriate her as a feminist and as a womanist, but she doesn’t exist without her Catholicism. She’d be the first to say that, and I was blessed to work with her for 20 years at Princeton.

1:07:05 CW: So it’s those kind of acknowledgements. I would say that that’s true across the board. We could say the same thing about some of the great Islamic thinkers or the great Buddhist thinkers. And my dear sister, bell hooks, is a Buddhist, and I’ve written works with her. I have great respect for her. I was just at her Center, her Institute there in Berea College recently, and her Buddhism goes hand-in hand with who she is. There’s no doubt about that. That’s part of the beauty of it all, though, brother, is that everybody’s who they are and not somebody else.

1:07:38 SC: Yep. Democracy is not about making everyone alike, it’s about creating a world where we can all be ourselves.

1:07:44 CW: Absolutely, absolutely.

1:07:47 SC: Alright, we’re running out of time. I’m sure we could talk for hours more, but I have two more questions, just slight deviations from the theme, but one is, I was reading just before we came on a story about that lecture course you already mentioned you’re teaching with Roberto Unger, and one of the provocative little things you say is that one of your goals as a philosopher teaching students is to unsettle them, to make them question a little bit some of their more standard things. So let me turn it around in the best critical tradition: What is it that unsettles you? What is it that you’re least confident about about the things that you care so much about?

1:08:31 CW: Well, it’s what hangs in my closet, and is one of the themes of my writings really for the last 30 years, which is nihilism. The great Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel used to say the largest ecumenical movement on the globe is nihilism.

[chuckle]

1:08:49 CW: And it comes in different forms. There’s secular forms of it, there’s religious forms. By nihilism, what he very much meant was the triumph of Prosemicus over Socrates in Plato’s Republic. Might makes right. Or the grand inquisitor, again, in Brothers Karamazov, where you actually give up on any quest for truth or beauty, and you begin to manipulate and dominate each person by keeping them in the mist, in the fog so they can’t see clearly, so they don’t feel deeply, especially about others on other parts of town, other parts of the world, and that they end up acting very much in a spirit of complacency and conformity rather than with courage. And I’ve been wrestling with nihilism for a long time. Schopenhauer’s always right next to my bed in terms of the figure who unsettles me probably more than most.

1:09:46 CW: The other thing that unsettles me would be the increasing lovelessness and joylessness in the late modern world, and Dostoevsky said, “Hell is those who suffer from the incapacity to cultivate love.” And lovelessness is predicated on pushing aside vulnerability, pushing aside invincibility, pushing aside humility. And so in relationships and how would we connect to each other, kindness, sweetness, gentleness, pushed aside. It’s all about posing, posturing, spectacle, image, trying to manipulate in order to pursue our careers, our next opportunity. And when careerism and opportunism become dominant, even in the spirit of a people, then you really begin to cut off the very things that go into love. And so you end up with a whole lot of pleasure but not too much joy. A lot of American culture is a joyless quest for insatiable pleasure. And the pleasure is generated by a certain kind of titillation and stimulation owing to the distractions. When Eliot says we’re distracted from distractions by distractions, and so much of US culture is just weapons of mass distraction. And back to your point about education, see, education is about the formation of the right kind of attention, to attend to life and death and love and joy.

1:11:21 CW: And the things that really, really matter, not the superficial things. But when the superficial things become the most dominant thing, then when younger generation grows up with bombardment to and attention to the superficial, the status, the appearance, the image, the spectacle, and they don’t have access to the raw stuff of caring and nurturing that are required for genuine love and joy, then you end up with a whole culture that suffers more and more from the inability to really love in relationships, to love themselves or to then experience the fruit of love, which is joy.

1:12:10 CW: So it’s all about pleasure. You see, that is spiritual decay at its most profound level, and that unsettles me deeply, ’cause I grew up in a context, but I had so much love in my family, in the West family, in the [1:12:23] ____ baptist church, and in the singing groups and in our athletic groups and in… The love that we were talking about at Harvard, with Hilary and Stanley and John, and the others and with Rorty and Roland, we had some deep love going on, we really did. Raymond Geuss, one of my great teachers, is still going at Cambridge University. We weren’t just teacher pupils, we really had a love and respect and care for one another.

1:12:52 CW: And I’m not saying that those things are impossible at all, I’m just saying that we’re living in such a decadent culture where things are pushing against the love and joy and much more toward the lust and pleasure, and that lust for domination, the lust for attention. That’s Trump again, you see, that he becomes a sign and symptom of the spiritual decay, you can see his life, the lack of the joy. I saw it in Charlottesville with the neo-fascist brothers when we were confronted with them, and they cussing at us and so forth, and you look in their eyes, brother Sean, and you see depths of joylessness. It’s not just the hatred and the contempt.

1:13:32 CW: The joylessness, you say, “Good God, is this brother… I hope he has some love in his life, ’cause I’m here fighting him because I love somebody, and I love something bigger than me.” Now, he’d come back and say, “Well, I love my race, I love by my cloak [1:13:49] ____ and I hate Jews and I hate Black people and I hate gays and so forth, and so on.” You’d say, “Yeah, but that kind of loyalty is not the kind of love I’m talking about.” That’s idolatry at that point.

1:13:58 SC: Well, so I think maybe the answer to my final question is implicit in the answer you just gave, but the flip side of that, I always like to end the podcast on an optimistic note. Where is it that you find hope for… To fight against the nihilism? Maybe to anticipate a little bit, but as bad as things have been, and this is 2020 of all times, but the tremendous energy out there on the streets and just even… Look, even the energy of people arguing with each other on Twitter, for that matter, it’s like at least they care. There’s a lot of passion out there. It gives me a little bit of hope; even if the passion is sometimes misdirected, it hasn’t gone away.

1:14:44 CW: No, I hear you, I hear you. I’m thinking of that line in Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound, remember how he ends that great poem where he talks about the hope and the capital H, hope, that creates from its own wreck, the very thing it contemplates. So that there’s a possibility actualized every day, not just on the streets in terms of political demonstrations, marvelous, marvelous multi-racial and multi-gender, multi-sexual, orientational display, but it’s in what you do in terms of the scientific community. The magnificent energy, vitality and vibrancy in terms of trying to make sense of the world with the argumentation and inducing of evidence and so forth and so on. That those things themselves can be co-opted, those things themselves can be colonized by powers-that-be.

1:15:47 CW: We still have a whole host of spaces that are countervailing against any attempt to colonize your own scientific community. So that energy and vitality in and of itself is part and parcel of a certain quest for truth and even a quest for beauty in terms of the symmetries and the incongruities that you all see in the cosmos and in the world. So that I do believe that there’s always some hope. But for me, hope, it’s as much a verb as a virtue, you know, brother. As long as you’ve got some motion, some activity, some dynamism taking place, tied to the love of truth, goodness, beauty, then we’ve got some real possibilities.

1:16:33 CW: Now again, as a Christian, I still have a love of the holy and a love of God, but that’s a very complicated issue that we’d have to have another conversation on, in terms of the traditions and stories and narratives that go into the sustaining of particular versions of Christianity that do overlap in a lot of ways with your poetic naturalism or just Jeff Stout’s naturalism or Santayana’s naturalism or even some of the naturalism of the creations going all the way back. But it swerves and it’s different as well, because that love that was manifest in that Palestinian Jew named Jesus that was unleashed on that cross is a very, very powerful powerful narrative and story.

1:17:27 SC: No question, yeah, it means for… Among other things that we will never run out of things to talk about, which is good, because I hear that you have a podcast starting up. Is that true? Did I make that up?

1:17:36 CW: Oh, yes, my guest is Trisha Rose, brilliant, magnificent person, human being that she is. We have a great time. Thank God for brother Jeremy, he was the visionary behind it.

1:17:47 SC: So what is the name of the new podcast, if people want to search for it.

1:17:49 CW: It’s called The Tight Rope.

1:17:50 SC: The Tight Rope. Balancing.

1:17:51 CW: It’s called the Tight Rope. On the tight rope, looking for hope on the tight rope.

[laughter]

1:17:58 SC: So good, Dr. Cornel West, thank you so much for being on the Mindscape Podcast.

1:18:02 CW: Thank you so very much. You stay strong, my brother.

1:18:04 SC: You too.[/accordion-item][/accordion]

Pingback: Sean Carroll's Mindscape Podcast: Cornel West on What Democracy Is and Should Be | 3 Quarks Daily

Would you like to suffer violence from one wise and benevolent person or from a group of people who are mostly stupid (average) and selfish? Given those options it’s not weird people choose the wise and benevolent dictator; we all assume the dictator mostly agrees with us anyway.

If reason worked to change minds people would not believe in god(s). I’m not going to waste time on the impossible task of using reason to change the minds of fundamentally unreasonable people.

And then there is capitalism …

Is it weird I prefer anarchy (opt-in democracy)?

Loved this show! wide ranging, full of energy, informative and not over labored, but quick. Labored points are for papers and well edited books on philosophy or political philosophy, this was quick exchange, and fun.

Ask your initial question this way:

“Would you rather be ruled by majority rule, or by one politician, who promotes him/herself as wise and benevolent?

Entirely different results.

Two very educated guys talking about very important practical issues in a way completely inaccessible to the people with the most to lose.

I’m not suggesting that these podcasts should be dumbed down, but if you want to appeal to all those folks you say need to be educated stop quoting Dante and start quoting Yoda. This is a podcast a Trump supporter could point to to illustrate how out of touch those left wing Bernie Sanders supporters are with real working class people. Intellectual elitism at its finest.

It’s ironic to lament that only 33% of people have a collage education but then Discuss the problem in such a way that only people with a college education could understand it. If you want to keep people from following a disaster like Trump you need to speak to them in a language they can understand. This seems to be a common problem in the liberal intelligentsia. Talking about the philosophical roots of democracy is fun but don’t expect it to make any difference.

Gord..I’m a Trump supporter but also enjoy Sean Carroll and Cornel West. I understood every word they’re saying. Sam Harris is an out and out Trump hater but Sean and Cornel are diplomatic enough to keep their feelings under control.

One thing I do find from these folks is no intellectual rationale for Trump except to say he is a nationalist who appeals to some underlying racial prejudices in the populous. What we as Trump supporters see is an underlying prejudice in the intelligenceia.

Case in point, no intellectual recognition of the globalist agenda and aggressive Chinese agenda which effected red states industrial base fueled by the American business class leaving the working class underfoot. No, Dr West the Harvard professor, the Harvard University which has an outreach university in Beijing and Dr Carroll the Cal Tech professor who interfaces with Beijing physicists as part of his scientific international community. Get my drift?

BTW I’ve read West, Carroll, Dennet, Chalmers, Augustine, Santayana, Russell, Whitehead, Schopenhauer, Dante, McGinn…..

I would adore doing a podcast with these gents.

Victor Panzica