Aristotle conceived of the world in terms of teleological "final causes"; Darwin, or so the story goes, erased purpose and meaning from the world, replacing them with a bloodless scientific algorithm. But should we abandon all talk of meanings and purposes, or instead conceptualize them as emergent rather than fundamental? Philosophers (and former Mindscape guests) Alex Rosenberg and Daniel Dennett recently had an exchange on just this subject, and today we're going to hear from a working scientist. David Haig is a geneticist and evolutionary biologist who argues that it's perfectly sensible to perceive meaning as arising through the course of evolution, even if evolution itself is purposeless.

Support Mindscape on Patreon.

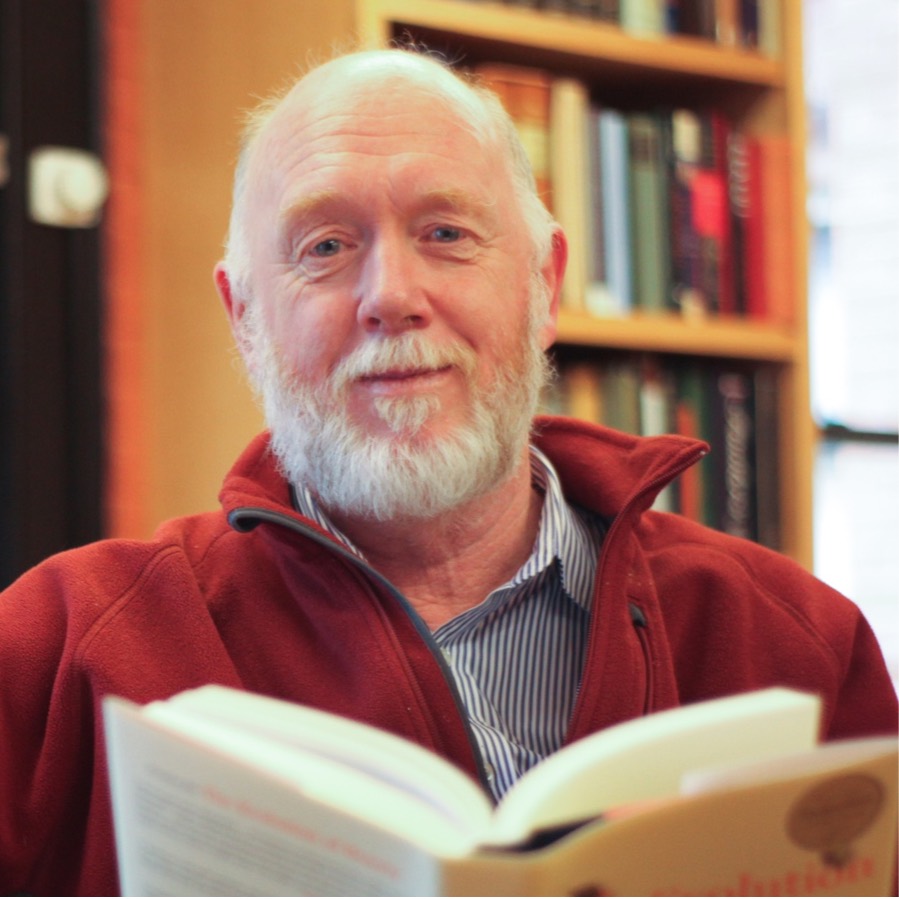

David Haig received his Ph.D. in biology from Macquarie University. He is currently the George Putnam Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University. His research focuses on evolutionary aspects of cooperation, competition, and kinship, including the kinship theory of genomic imprinting. His new book is From Darwin to Derrida: Selfish Genes, Social Selves, and the Meanings of Life.

[accordion clicktoclose="true"][accordion-item tag="p" state=closed title="Click to Show Episode Transcript"]Click above to close.

0:00:00 Sean Carroll: Hello, everyone, and welcome to the Mindscape Podcast. I'm your host, Sean Carroll, and today we're going to dive once again into the meaning of life. In fact, the meaning of many things. What is meaning? What are purposes that we have out there in the world? But we're going to do this in a much more grounded scientific way than we usually do, or than people usually do when talking about these things, which is appropriate for the modern world. Back in the day, before the Scientific Revolution, before Darwin and his friends, you could imagine that purposes and meanings were simply part of the fundamental furniture of reality. If you were Aristotle or one of his successors, you imagined that a final purpose, a final cause was one of the things you needed to explain how things work. The final cause was the thing to which you aimed, right, your ultimate future goal. It was a teleological way of thinking about the world.

0:00:52 SC: But then along comes physics, of course, but mostly along comes Darwin, and Darwin is able to explain all of the species, all the biology we have around us in ways that don't refer to future goals at all, right? This is one of the secrets of evolution, that even though individual species can be very, very well adapted to their environments, it doesn't come from precognition, it doesn't come from planning for the future. Individual parts of our genomes shake about randomly or recombine through sexual reproduction and so forth, and they just figure out through trial and error which ones work for the situations they're in right now. There's no forward-lookingness at all. So here's the puzzle then. If that's true, if Darwin is right and there is no forward-lookingness in the process of biology, why is it that so many things in the world, in the natural world, seem to have purposes, seem to be existing for reasons? Right?

0:01:48 SC: This is what drives people to intelligent design and things like that. Why is the neck of the giraffe so long? Well, it seems to have the purpose of reaching the leaves up there in the tree, right? And on a piecemeal basis, you can account for these things using non-teleological evolutionary biology, but maybe you want a bigger picture view, an idea of how purposes and meanings come to exist through the non-teleological, or dysteleological is the technical word, operation of ordinary natural selection.

0:02:18 SC: So today's guest is David Haig, who is a professor at Harvard of organismic and evolutionary biology. He's a theorist, and so he thinks widely about many, many things, and he has a new book out called From Darwin to Derrida: Selfish Genes, Social Cells and the Meanings of Life. And I'm not going to give away too much. We'll talk about it on the podcast, but the basic idea is exactly this, to sort of figure out how purposes can evolve despite the fact that evolution is not forward-looking. To be very honest, I have a difficult time translating or sort of saying what he says because it's actually very similar to things that I say in my own book, The Big Picture, and so I end up putting my words into his mouth, which is not fair, so you should listen to what David has to say.

0:03:02 SC: It's a fascinating sort of synthesis of a whole bunch of different ideas from different places. And the other reason I wanted to invite David on the podcast is because I was tickled by the appearance of Jacques Derrida's name in the title of his book. Jacques Derrida, one of the leading lights of post-modern philosophy and modern theoretical French philosophy, which, as I mentioned in the podcast, is kind of anathema to a lot of sciencey people on this side of the Atlantic Ocean especially. And it's interesting to me because I think that Derrida and his post-modern friends get way too much flak and they're not taken nearly seriously enough by scientists, my friends who are scientists out there.

0:03:39 SC: I'm not going to say that I agree with everything that Derrida or other post-modernists talk about, but there's a certain anti-intellectual attitude that doesn't actually read the books. A bunch of people, right, just strawmans them as forces of anti-reason and so forth. And I think that in the case of Derrida and others, there is something useful in there that can be used even if you disregard or disagree with other parts of it. And I think that's exactly what David does, his particular reason for invoking Derrida's name in the title of his book has to do with a similarity between the fact that Derrida makes a big deal about how meanings in texts are not foundational. They are not part of the ultimate structure of the text, just like Darwin comes along and says that purposes and meanings are not part of the fundamental architecture of reality or science.

0:04:28 SC: To Derrida, meaning is continually being re-written as different people read texts in different ways, and other texts are written and so forth. And so, David thought it would be funny to actually compare them in the book. And he has a joke, I'm not going to give away the joke, for the joke appears in the podcast anyway. I think that people should be much more open-minded about parts of academic work that are very far away from theirs, seem very alien to them and are hard to understand, but might actually have something to offer, even if it's only piecemeal. And I think that Derrida is a good example of that. So anyway, that's my little sales pitch for reading postmodernism as a modern physical or natural scientist. And with that, let's go.

[music]

0:05:27 SC: David Haig, welcome to the Mindscape Podcast.

0:05:30 David Haig: Welcome, Sean.

0:05:31 SC: This is going to be a conversation where I have to restrain myself a little bit, because you've written a book that in many ways is sort of complementary to a book that I wrote called The Big Picture. There's a lot more evolutionary biology in your book, there's more physics in my book, but it's going from the natural world of science to questions of purpose and meaning. So maybe to situate ourselves, what would cause an evolutionary biologist to write a book about purpose and meaning?

0:05:55 DH: So since my undergraduate education, I have been told in biology that using teleological language is unscientific, that anthropomorphism is another sin in biology, and yet when we think about biology, the first thing that comes to our attention is the purposeness of living beings, and the scientists who decry using teleological language will be quite happy talking about receptors and signals and information transfer within cells, not to mention transcription and translation, which are very teleological concepts. So I'm 62 and I was becoming increasingly frustrated that in evolutionary biology, good ideas based on arguments from adaptation were being rejected for bad philosophic reason.

0:06:53 SC: That's very interesting. So do you think that when you say bad philosophical reasons, I'm very familiar with the relationship between physics and philosophy, which is rather a hostile one from the physicist's point of view, and I think that's bad. How do biologists feel about philosophy? When you say bad philosophical reasons, are these just biologists offering reasons that are philosophical, even though they wouldn't characterize them that way, or is it that they're actually listening to bad philosophy?

0:07:19 DH: No, I think that they would feel that their empirical research is independent of philosophical presuppositions, but usually they have a whole series of assumptions that they're making that they don't question themselves, and so that's why I thought I needed to delve into some of these assumptions within biology.

0:07:41 SC: That makes a lot of sense. I often say that you don't have a choice as a scientist to not do philosophy, but you can do it in an informed way or in a less informed way. So speaking of philosophy, let's, to sort of, again, set the stage a little bit here. Like many people, you go all the way to Aristotle when you're talking about causes and purposes. So maybe share with the audience. You've already used the word teleology, explain what that means and how it relates to our notion of causes and purposes.

0:08:11 DH: So teleology comes from the Greek word telos, which refers to the end of something. For biologists, they will know of telomeres, which are the end of a chromosome. So Aristotle was trying to think about different explanations we offered of things, and he offered four different kinds of explanations. One was explanation in terms of the material from which something was made, another was an explanation in terms of the idea or form of the material, so that the same material could make many different things that differed in form. And he also, what set something in motion, and then the purpose, or the thing for the sake of which something existed.

0:09:02 DH: And when Aristotle's ideas were translated into Latin, they used the Latin term causa, which was originally a legal term, to show probable cause, still to this day a legal system, and so his four causes came down in medieval philosophy as the material cause, that was the matter of which something was made; the formal cause, which was the essence of the thing, what made of that matter one kind of thing rather than another; the efficient cause, which was what set something in motion; and then the final cause, which was the thing, the reason why the thing existed, the end to which it moved. And so in the Scientific Revolution physicists largely rejected formal and final causes in favor of efficient and material causes, that all explanation was to be of matter in motion.

0:10:03 SC: And that was highly successful in physics, but in biology at that time, people continued to think in terms of purposes and final causes. So William Harvey described the circulation of the blood by thinking about what might be the function of the valves in veins, and so up until the 19th century, final causes, explanations in terms of purposes, were used by most physiologists and biologists.

0:10:36 SC: It's interesting, because the phraseology, the translation of Aristotle's ideas into the word cause, doesn't quite fit our informal notion, right. Like a material cause, the stuff out of which something is made, we wouldn't call that a cause at all, but the final cause, the purpose and the efficient cause, whatever makes it, those are things that really do resonate with our notions of causes, and as you point out, science has had something to say about these notions.

0:11:04 DH: Yes, yeah. So I think... So the word Aristotle was using, you might think of it as more like an explanation, and so he was talking about four different explanations that moved into the Latin as causa and then into English as cause. The final cause has been the most controversial within science, because it seems to be explaining the existence of something by the effects that it has, and for the effects that are coming after... Sorry, the effects come before the cause, and that seems to be reversing our conception of causation.

0:11:50 SC: Right, right. Well, so and this is where we get really into the nitty-gritty, so we're not going to save the best for last, we're going to get right into it right now. When Darwin comes along and explains natural selection, which is evolution and the name of the department you're in at Harvard, it contains that word evolution in it. In some sense, one interpretation was, he got rid of the need for teleology, for purpose. You know, when evolutionary changes happen, they don't know ahead of time what is going to be the effect that those changes have and they're selected after the fact.

0:12:31 SC: So I think a lot of people would say, we don't need to talk that language anymore of teleology, Darwin explained it all away, but you want to say that nevertheless, that language is useful somehow.

0:12:40 DH: Yes, I think Darwin's own position was that he hadn't eliminated teleology, that he had naturalized purpose in nature, and so that previously the conception of purpose required some mind which had intentions and plans, and so natural theology had explained the purposiveness of living things as evidence for the creator. And what I think Darwin showed is that you had a perfectly natural process which didn't have a purpose, that created living beings, living beings with purposes and intentions evolved.

0:13:19 DH: So my feeling of Darwin's own position was that he hadn't eliminated purpose, and he actually, in his own writings, particularly on plants, used a purposive language frequently, but that he had got rid of the need for some supernatural source of the purpose. And I think the heart of the teleology in Darwin only really became clear when we had a concept of genetic materials that are copied and transmitted from one generation to the next. And so now the effects of the gene can determine whether that gene is copied or not. So it's what a gene does that is responsible for its presence in the population. Of course, it is what it did in the past that is responsible for its presence now, but it will tend to do again the things that it did in the past in the present, and so there is a forward-looking nature to natural selection because of the recursion that is present in reproduction.

0:14:21 SC: Right. And this is a deep idea that maybe is worth going into more details about. So what you're saying, what you seem to be saying, is that not only did Darwin remove the need for a mind designing these things, but that somehow the wonderful trick that evolution pulls off is to give things purposes without directly looking into the future, without directly having foresight, it works in the present moment, but in such a way that usefulness in the future comes along for the ride.

0:14:53 DH: Yes, so Darwin got rid of the idea that there was a purpose in creation, that evolution was working towards some future goal, but he created a process that created beings like you and I that interact with their environments in purposive ways, so the evolutionary process itself doesn't have any purpose, direction or end, but it creates meaningful beings that act purposely in their environments.

0:15:25 SC: Yeah, maybe we can make that more precise or maybe it's something that is just hard to make precise. I mean, when do... When, can we point to something that an organism is doing and saying, this is a purpose for this aspect of the organism or this action that the organism takes?

0:15:44 DH: So if one of its past actions is responsible for... So now I'll do it specifically, not from the organism but from the genetic text. If one of the effects of a particular genetic text is responsible for that text being copied and being present today, then it is those effects of the text that account for the present, presence of the gene. So we have genes that cause hearts to pump, which circulate oxygen to the tissues of the body, that is their function. In the past, organisms have survived because they have functional hearts that distribute oxygen, and so it's the past functioning of the heart that explains the presence today of genes that produce functional hearts.

0:16:38 SC: Do you tend yourself to think of this in terms of emergence and levels of description? I mean, can we say that in some sense at the microscopic level of the molecules inside our DNA, things just obey the laws of chemistry, right, I mean, they just bump into each other and combine or recombine and talk of purposes isn't very helpful. But once we look at a higher level where you talk about genes or organisms or traits, then the language of purposes becomes more useful.

0:17:09 DH: So I would say both yes and no. Yes, in the sense that natural selection is just an explanation of an incredible complicated process of efficient causes of organisms living and interacting with other organisms in a complex environment, and so to summarize it as selection for some particular character, it's just an efficient way of talking about that very, very complex process that, of course, obeys physical laws. So I'm a real believer that there are no special causes, that everything is ultimately physical and chemical causation, so that's the yes to your question. The no is to somebody who says that everything can be built up from the ground up, and then you have emergence at higher levels.

0:18:05 DH: The nature of natural selection is that its events in the world of ecology, in the world of interactions among organisms, who gets to mate, who gets to reproduce, that have effects at the molecular level. So that the explanation, for example, of why the sickle cell mutation occurs in a hemoglobin gene in people of African descent is because they came from an environment where malaria was endemic and that particular amino acid change provides some resistance against malarial infection. So the causation is going to the amino acid in the protein from the complex world of epidemiology and the subsistence agriculture of those people in the past.

0:18:55 SC: Well, yeah, so we see where we're getting immediately into tricky philosophical waters about... One of the many issues that is brought up by this kind of thing is what counts as real, right? Our mutual friend, Dan Dennett, previous Mindscape podcast guest, and he wrote the forward to your book, he really likes to emphasize that these higher level emergent things are real if there are patterns, you use the word efficient, an efficient way of talking about things, well, then that's a real feature of the world, and so is it safe to say that purposes fall into that category?

0:19:30 DH: Yes, I would accept them as being real, and we see that in our own actions. You and I are talking to each other, we have a purpose of producing this podcast, there is some incredibly complex physicochemical explanation of what we are doing, but that explanation is actually not particularly explanatory of this sort of questions I ask and the... Well, the questions you ask and the answers I give to them. So explanation at that level, the physicochemical substrate of it is essentially irrelevant to explanation at that particular level.

0:20:14 DH: And I would say the same is true of understanding the adaptations of organisms, sometimes physical chemical information is relevant, but sometimes it's just a distraction. I think a really interesting comparison now is to the success, the current success of artificial intelligence. So artificial intelligences are trained by a process of selection from feedback from their output back into the nodes of the network. Now, an artificial intelligence network is absolutely transparent, you can get a printout of all of the connections within the network and their strengths, and yet people in artificial intelligence find it very hard to understand how the network achieves turn what it does.

0:21:09 DH: The modification of the network has been non-linear and complex by feedback from the complicated environment, and so actually just knowing the way that electrons are flowing through the network is not giving much insight into what are the capabilities of that particular artificial intelligence.

0:21:30 SC: Good. No, I think that we're exactly on the same wavelength here, which leads me to ask, are there people who are not on this wavelength, are there people who disagree with you about this particular conception of how we should think about where purposes come from in biology?

0:21:45 DH: Yes, it's an absolute part of dogma for most biologists that using purposive language is non-scientific, and I am still regularly corrected to this day in the papers I submit to scientific journals that my use of the language of purpose is inappropriate and that I am making some fundamental mistake about biological organisms. A related criticism is against creating other organisms anthropomorphically, as if they were like humans, and I find that rather strange. You know, it's okay to treat a slug, I talk about slugs quite a bit in the book, as if they were like a machine, but totally inappropriate to think of them as in some ways like human beings, even though they share... Even though I would say a slug and a human being are much more similar to each other than they are to a traffic light or even a digital computer. But for mechanistic biologists, machine analogies are appropriate, whereas talk of purposes and reasons and intentions are inappropriate in explaining the behaviors of living things.

0:23:03 SC: So I can think of a couple of reasons why that might be the case. Is one of them just that there's an ongoing debate in evolutionary biology about the role of adaptations and evolution versus just accidents. I just had Sean B. Carroll, the biologist, evil twin of mine on the show, and he is on the side of really emphasizing how important accidents are, but clearly there's also an adaptationist aspects to evolution. Is that part of why people resist the talk of purposes, 'cause sometimes things just happen by accident?

0:23:36 DH: So accident, of course, is a very, very important part of natural selection. All mutations, which are the raw materials on which the environment selects, are essentially copying accidents. So I'm a real believer in the importance of chance, but which of those chance, which of those mutations are interpreted by the environment as adaptive or non-adaptive, that's a post-hoc judgement by the environment. So DNA sequences are accumulating information about past natural selection, so random processes are important, but I think people in evo-devo, like the other Sean Carroll, part of the reason why they want to emphasize the random against the adaptation is this teleophobia that's sitting there. If you're a serious scientist, there's something more rigorous and hard-nosed about looking for random explanations rather than adaptive explanations. It's perceived as being soft or poor science.

0:24:45 DH: Now, it's very, very easy to make a bad adaptationist argument. I'm not saying that identifying what the adaptations of organism are is easy, but to just give up on that process and to focus on random processes with neutral evolution, which by definition doesn't make a difference for the organism, I think is missing what's really, really distinctive about biology.

0:25:13 SC: Yeah, I think that everyone probably agrees that both neutral genetic drift happens and is important, and also as adaptation and selection happens and is important, then balancing them is tricky. And then the other thing that happens in biology, at least as opposed to physics, for example, is that the discussion is embedded in this political and theological context in a way that physics just isn't. Are people worried about using the vocabulary of purposes because it does sound a little too mystical somehow, or a little bit too much like giving in to the side that is opposing evolution in the first place?

0:25:54 DH: So for some people, I think that is one of the motivations that they feel that if you use the language of purpose, you're going to let in the supernatural and God back into biology. I think there's another resistance, a political resistance to adaptationist theorizing, that could be exemplified by Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin. The idea is that thinking that human nature is in some sense adapted, fitted to a particular world, is perceived as being a constraint on the possible worlds and the possible cultures that humans can live in. And one of the purposes of my book, okay, so in writing it, is that I wanted to argue that we have evolved to be free and to make our own choices in environments that have never been experienced before, and also that our human nature expresses the purposes of our genes, but they need not necessarily be our purposes as individual organisms.

0:27:09 DH: So we need to respect human nature, but I'm somewhat of an existentialist when it comes to determining what our own purposes should be. Our genes don't care about us, if they can get their way by our misery or by our joy, they will achieve it. And so we shouldn't care too much about them.

0:27:29 SC: That's very interesting. You do use the example in the book of a person who is very promiscuous, but uses birth control, if I'm remembering the example correctly, and you try to make the argument that the original purpose, in some sense, that their motivation to be promiscuous came from might very well be to spread their genetic material widely, but the actual way they're doing it doesn't actually succeed in that at all, but it's still okay to use this language, but certainly it's a reminder that it's tricky and we should be careful using this language.

0:28:03 DH: Yeah, I recur to that example a number of times, for two reasons. So one of them is the reason that you just gave there, sexual activity is pleasurable, because the incentive of pleasure has been the way, the reason why people have engaged in activities that have led to reproduction and genetic transmission. But we can gain the pleasures from those activities without conception. We can use contraception. The second reason I use the example is it makes a distinction between our psychological motivations and the reasons why we have those motivations. So a philanderer would not engage in sexual activity to have children, they engage in sexual activity because it's psychologically pleasurable. But the reason why it is pleasurable is because in the past, that sort of behavior has led to reproduction, but we are not enslaved to repeat the past, we should respect our genetic materials, but not too much.

0:29:18 SC: Well, and also, I think you alluded this a little bit, but when we tell the story of why we have this urge to do sexual activity, there is a danger that... It's a little bit more storytelling than scientific, that we tell a just so story and don't rigorously test it. And how do we know... And this gets into the whole useful, the whole question about how we can become good evolutionary psychologists, not just biologists, how do we know that our adaptationist stories are on the right track?

0:29:50 DH: So that requires critical testing to find distinguishing experiments that can be done that can separate out alternative explanations, particularly in evolutionary psychology. I think it's very, very important to test ideas across the wide range of human cultures. So Joe Henrich, who's a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard, has made, has written a book recently on how distorting the view of human motivations it is to just focus on undergraduate students in evolutionary psychology labs.

0:30:35 SC: I don't see why they wouldn't be perfectly typical of all human beings ever, but I guess that's a claim you can think about, so, okay, good. We've jumped ahead to some of the topics that I am interested in getting to, but before we just sort of indulge in them, let's dig down into a little bit into the details of what's going on. I know that what some of the work that you've done as a research evolutionary biologist emphasizes the fact that we have sort of competition going on within ourselves. Like if you try to say whether this particular gene or this particular part of your body has a certain purpose, those purposes might not always align.

0:31:16 DH: Yeah, so the traditional model of the organism has been that the organism is a machine in which all the parts are working together for a common good, and I am interested in situations where that internal cooperation breaks down and different genes within the individual have different fitness function and are evolving to pursue contradictory ends. I came into it actually, particularly in an interest in genomic imprinting, where genes of maternal and paternal origin within the same individual are subject to conflicting selective forces.

0:31:56 SC: So you'll have to explain more about that. So you're saying that our inheritance from mom and dad might be at odds within ourselves. This sounds like a psychologically rich vein to mine.

0:32:08 DH: Yes, so we do know that there are some genes that are differentially expressed when you get them from mother and father. And so this was called imprinting, because the idea is that there has to be some mark put on a gene that said in the last generation that was in the male or a female body, and that mark must be inherited by the offspring and cause the gene to be expressed in a paternal-specific or a maternal-specific way. But then the imprint must be able to be erased and reset, because the genes I get from my mother with the maternal imprint, I'm passing on to my children with the paternal imprint.

0:32:46 DH: So you can think of imprinting as a kind of temporary annotation on the text, informing the gene with, in which particular context it's behaving. So I'm particularly interested in this in embryonic and fetal development and in the development of the placenta, and there genes of paternal origin are tending to favor greater growth of the placenta, which is the structure that's extracting resources from others. And genes of maternal origin in the same organism are inhibiting placental development. And so there's an internal conflict on the size of the placenta, and that comes to some sort of a social resolution of that conflict, which has to be compatible with successful development of the child, but it doesn't mean that there aren't conflict costs involved. So that this is looking at the genome not as a completely cohesive and cooperative entity, but as riven with internal conflict. And I'm particularly interested in situations where evolution by natural selection ends up with results that are not good ideas, that aren't actually increasing the well-being of organisms.

0:34:02 DH: I think a useful analogy here is to economics, so we're all... For me, with Adam Smith's idea of the invisible hand. The basic idea there is that everybody following their own self-interests, everything gets delivered more efficiently at a cheaper price, and the invisible hand is good for many aspects of the economy, but it's particularly bad at the provision of public goods, as we're seeing in global warming and the collapse of the world's fisheries and congestions in the streets within cities. So these are situations where there are public goods that nobody owns and everybody enjoys, and the self-interest is very bad at providing public goods.

0:34:50 DH: And the same thing applies in evolutionary biology, the idea that natural selection is leading to ever-increasing fitness and well-being of an organism is true in some contexts, but I'm interested in situations of public goods where evolution by natural selection leads to outcomes that are not necessarily efficient. And so an example I would use of that, they call it the tragedy of the maternal commons, that you have embryos, fetuses, that are over-exploiting maternal resources during pregnancy, because if one offspring does not take those resources, they go to another offspring that isn't genetically same as that one.

0:35:35 DH: And so while the cooperative outcome would be the most efficient, you lead to a situation in which there are conflict costs, and I think this explains why things go wrong so often during pregnancy. Of course, at first sight it's strange, my heart and my liver have been functioning very well for for 62 years, and yet during pregnancy, you have a natural process that only lasts for nine months, and yet many things go wrong during it. And I would argue that the reason why pregnancy doesn't work as smoothly as the normal functioning of the body is that in normal bodily functioning all the parts of the body are genetically identical to each other and working towards survival of that body, but in pregnancy, you have two different genetic individuals interacting with each other and natural selection can act at cross-purposes, there's a sort of politics going on, and we know that politics does not always lead to efficient outcomes.

0:36:36 SC: I've heard that, yeah. I've seen it in action even sometimes, but maybe you could illuminate a little bit more the molecular biology here, because I think, like many people, I have this simplistic high school notion, high school biology notion of, we get half our DNA from mom, half of it from dad and now it's our DNA and it all works together. But you're saying that there's somehow a chemical marker in there that tells me whether it's from mom or dad, but that there's not a chemical marker that tells me about whether it's from grand-mom or grand-dad.

0:37:08 DH: So we don't definitely know the answer to the second part about grandparental origin. But we do definitely know that there are markers of maternal or paternal origin, and for many of the genes, this is by a process called DNA methylation, so the cytosine nucleotide can have a methyl group attached, that's just a single carbon atom with three hydrogens attached. And so there are enzymes that can attach methyl groups to cytosines and enzymes that can remove that, and then during DNA replication, there is also a process by which the daughter cells inherit the pattern of cytosine methylation from the parental cell. And so now you've got all the molecular tools for putting marks onto DNA that are stably transmitted through many cell divisions and even from parent to offspring. But then you also have biochemical processes that can remove those remarks and reset them. So this is the example I was giving of an annotation of the genetic text.

0:38:21 SC: Well, and it leads us directly into something you mention in the book also, which is this idea of the selfishness of not just people or organisms, but of different substructures. Richard Dawkins very famously suggested that we think of genes as being selfish, and so... I don't want to put words in your mouth, but you think that there is a sense in which that's a good way of thinking about even individual genes.

0:38:44 DH: Yes, no, I think that the adaptations of genes are for the benefit of those genes, so in that sense, the genes are being metaphorically selfish. I think that genes are the direct targets of natural selection, they are the selfish agents. That does not mean that genes may not construct bodies, individual organisms, that achieve the selfish ends of their genes by cooperative behaviors. So I'm thinking of individual organisms or as interpreters, as I call them later in the book, as being different kinds of entities than genes. So genes in Dawkins' terms are selfish. That does not necessarily mean that the organisms they construct need be selfish, they sometimes are selfish, but they can also be cooperative.

0:39:43 SC: Well, maybe this is a good place to ask a confusion or a fuzzyness I've had for a long time about this, because genes, in some sense...

0:39:51 DH: Hi, Sean, I've lost you.

0:39:54 SC: We know what a gene is, some collection of DNA that does some function, are the things that are passed down through evolution, through sexual reproduction, etcetera. But traits of organisms are what selection pressures actually act on, whether the giraffe's neck is long or whether the person is strong or swift or whatever, so how complicated is that relationship between the information carried through in the genes and the macroscopic traits that are actually subject to selection pressures.

0:40:23 DH: So the analogy I use at the end of the book is of natural selection as a poet, it is... If you look at a poet, a poem, it's how all the parts relate to each other, so that a word doesn't have an isolated meaning, but its meaning is with respect to the poem as a whole. But when you're writing a poem, it's always a choice among alternatives, this word versus that, they're judged by their effects on the whole, but the process of choice is between additive alternatives. And so natural selection is always choosing this genetic variant versus another variant, but it's in the context of their consequences for the complicated whole organism. So the way that I think of it is that natural selection is a mindless process, just choosing among simple alternatives, but choosing among those alternatives in terms of their effect on the complicated whole.

0:41:28 DH: And so that's how we get these very, very complicated organisms. Now, I think this has salutary implications for the attempt to understand organisms from the bottom up, isolating, it's just like isolating a single word in a poem out of context and asking, what is the meaning of that word, You're losing all of the poetry in life in approaching explanation from that bottom up perspective.

0:42:00 SC: Well, yeah, and once again, this speaks to the usefulness, I think, of this multi-level way of thinking, that different vocabularies have different explanatory power depending on your sort of level of resolution in which you talk about a thing, which immediately leads to the question of, if genes can be selfish then what does that imply about when people talk about kin selection or group selection, can we look at categories that are larger than individual organisms and their genomes and fruitfully apply Darwinian ideas to them?

0:42:35 DH: Yes, so an alternative to gene selectionism has been multi-level selectionism. I just think these are different ways of carving nature at the joint, that they're defining fundamental terms in different ways. So hierarchical selection theory or multi-level selection theory thinks as genes as the lowest level of a hierarchy, so that there are genes within cells and cells within bodies and bodies within groups and groups within ecosystem. And that's implicitly defining a gene as a physical object that's sitting within the cell, whereas the idea of the gene in Richard Dawkins and in gene selectionism is this is a bit of information that can be distributed across multiple levels of that hierarchy.

0:43:28 DH: And so, a gene in my liver has been selected because it promotes the propagation of its copies in my sperm cells, and in kin selection a gene in my brother's liver could be selected because it favors the propagation of its copies in my sperm cells. So there's nothing about gene selectionism that isolates the gene to a particular organism, that bit of information can be distributed across multiple levels of the hierarchy. So I think a lot of arguments in evolutionary biology, which is better, gene selectionism or multi-level selectionism are really semantic arguments, and the two sides are just using the same language, but defining the terms in very different senses.

0:44:16 SC: Well, this is a provocative image that you just gave to us, that in some sense, rather than the gene as a bit of DNA, we can think of it as a bit of information, and it's information that is spread out in complicated ways through a population, and despite the abstractness of that idea, you seem... Again, I don't want to put words in your mouth, but you seem to want to give in to the temptation to use a language of purpose and almost anthropomorphic ways of thinking about that, and I'm going to let you do that, but maybe defend that as strongly as you can, if you think this is a good idea.

0:44:54 DH: Oh, difficult, difficult questions. Part of the book is actually looking at the relationship between information and meaning. I've just decided that I'm being like the politicians we've heard on debates where I've changed the question somewhat.

0:45:12 SC: That's your right in this case, I'm not going to pin point you. Say the things you think are interesting to say.

0:45:17 DH: Yes, so I think the central chapter in the book is actually an account of the relationship between information and meaning, so that if you go back to Claude Shannon and his idea of information theory, information was just the uncertainty that was dispelled by perceiving one bit of information, one signal rather than another one, so it was a purely quantitative conception. And there was... It's been remarkably effective in computer science, in cybernetics and in all sorts of areas of technology, but there was a push back against that, that's not what we meant by information. In information, we're asking, what does it mean, that the information is about something, it refers to particular things in the world.

0:46:14 DH: And so I would like to separate meaning from information that... So the central concept of the later parts of the book is the idea of an interpreter which is an intentional being. It's like you and I, but it could also be a little bit of RNA that's taking information from the environment and responding in some adaptive sort of way. And so an interpreter is coupling what I in a physics term think of as two entropies. One of the entropies is an uncertainty and that is resolved by observation of information, and the second uncertainty, the second entropy is an indecision, all the possible things that the organism could do, and that indecision is a resolved by choice, taking an action. And interpretation is all the complicated processes that have evolved by natural selection that connect the input of information and the resolution of uncertainty into choice of action, resolving indecision into particular actions.

0:47:29 DH: Now, if you think about input output devices in purely physical terms, there are an incredibly large numbers of ways that you can connect up the same inputs to the same set of outputs, and most of those connections are non-meaningful. It's the process of natural selection that creates meaning in terms of output and choice of action from the information that the organism is acquiring from its environment.

0:48:02 SC: So I tentatively love this idea, I think that a lot of the audience members will be surprised that we've managed to get this far into the podcast without using the word entropy, 'cause I use the word entropy all the time. So may I ask, is this suggestion of thinking of information as resolving some kind of certainty into action, and that's the origin of meaning, is this a technical thing you've written up with all the equations and everything, or is this something that's more aspirational that you would like to see come true in further research?

0:48:31 DH: Well, I think actually that I deliberately avoided, so Shannon information, his measure of information is just like a measure of entropy, and that side of theory has been very well quantified and equations written, but I think the meaning of information, you could quantify how the... All possible choices of action of an organism and put a measure on that, but I think that trying to quantify there is actually missing the point of the relationship between meaning and information, that it's trying to substitute a quantitative measure for something that is inherently qualitative. So I guess that's one of the more radical implications of the book, that I think quantification is actually missing the point in some of these biological systems.

0:49:34 SC: I mean, you definitely caught me, I am very tempted to write down some equations and quantify this, but I think... I take your point.

0:49:40 DH: No, the equations can be written down and they can be useful, so different organisms almost certainly vary in the range and the repertoire of responses they can make to the information in the environment, and you might be able to quantify it, but the quantities themselves is not telling you anything about the sort of decisions that a slug makes versus the sort of decisions that a human makes, and the quantification is not telling you the reasons why this decision is made rather than another decision.

0:50:15 SC: Okay, yeah, that is fair enough. But it also... It opens up a new possibility. It's not very new by now, but another one of Dawkins' ideas is the idea of memes, not just of genes, of ideas themselves having a sort of evolutionary history, and I think this is a... I'm not sure what the status of this conception is throughout different academic fields, but you seem to be coming down on the side saying that, yes, we should think of ideas in this memeology kind of way.

0:50:47 DH: So I think ideas and culture clearly evolve and they are subject to analogues of natural selection, whether there's anything... When you think of a genus of physical objects, you can point to a particular sequence on a DNA molecule, and I don't think in memetic or cultural evolution that there's anything with that sort of simplicity that you can point to. So I think ideas of memes are good thought experiments for thinking about culture, but I don't think that there's going to be as well developed science of mimetics where we're treating particular ideas as the discrete memes as there has been in, for example, theoretical population genetics.

0:51:36 DH: In the feedback on the book I've received so far from biologists, the two points in which there's been most resistance is my use of teleological language, which people still resist strongly, and then the second is on the use of the language of memes, which many biologists feel that it's bringing the messiness of culture and meaning into biology, and then there's also resistance to that from the side of the humanities, which is thinking it's a far too simplistic approach to what they see as a very, very complicated process of cultural evolution. So I have sympathy with that position, but I also think that thinking about what are the reasons that cultures are the way they are, what are the meanings of those cultures, and that may not be always choices that humans have made, cultures evolve by processes that aren't planned by the people that are living in those cultures.

0:52:46 SC: Well, the people are objecting or at least commenting on your use of teleology and your use of memes, can we combine them to talk about selfish memes? I'm just interested in how far we can go in thinking of these rather abstract notions in sort of anthropomorphic language. And parenthetically, maybe the fact that the language is anthropomorphic is beside the point. A more interesting question is, are these the right units of analysis or levels of description where we can sort of get a lot of understanding by thinking in this vocabulary?

0:53:19 DH: So I would think now of the world we're living in with social media and the internet and email, we are just being bombarded all the time by bits of information, cultural items that are being sent out by other people in the hope that we will sort of pass, that they will change our behavior and that we will pass them on, and so how do we cope with that? There are some things that appeal to us and others that don't appeal to us, and the ones that appeal are then transmitted, and the ones that don't appeal don't become memes in the common sense. So if you look at an idea or a bit of news or a theory that goes viral, another biological metaphor, the reason why it goes viral and distribute is because of the properties that it has that appeals to the people who are seeing the idea.

0:54:25 DH: And now I'm not talking about whether it's true or wrong, whether it's real news or fake news, but the things that are transmitted are those that appeal to human minds, and so the ideas that are out there are evolving, often not deliberately by people, to appeal to be attractive to human minds, to be the sort of things that we want to transmit to other individuals. And that's really what I'm attempting to do in my book, I'm attempting to persuade, to try and make a set of ideas as persuasive as possible, so that your listeners and hopefully the book's readers will use them to influence their own thinking and to pass them on.

0:55:11 SC: Yeah, am I remembering correctly that in your book, you give Dennett credit for the idea that this is a way of thinking about what makes human beings unique in the world of biology, the fact that we have this memeology, the fact that we pass on ideas in abstract forms and those ideas come back in feedback and affect how we live and the societies we build?

0:55:35 DH: Yeah, so Dan Dennett has made that point, but it's a much older idea that the really fundamentally distinctive thing about human beings is that we have cultural evolution to an extent far on that of any other organism. And I think culture, that sort of open-ended cultural evolution, has been made possible by the origin of language. And so language is a medium that now allows ideas to be transmitted from person to person much more efficiently and with much higher information content than the sort of communication that we see in other organisms.

0:56:18 SC: And certainly one of the sets of abstract ideas that we have and that we use is what you might label moral philosophy, a sense of right and wrong. Like animals clearly, there are things that they want to do and things that they don't want to do, but they don't talk about meta-ethics in the same way that human beings do. So you have an angle on that, you're not afraid to say how these ideas that we've been talking about for the last hour have an impact on how we should think about right and wrong and questions of morality.

0:56:47 DH: Yeah, so I think that all of our repertoire of emotions, our benevolence, our generosity, our nastiness, our jealousy, these are all passions that have evolved as a means of getting us to transmit our own genes, if they will... We feel miserable because that in the past has been a way of in certain environments promoting our survival and reproduction, but now that we are cultural beings, we can look at that repertoire of feelings and emotions we have, and we can decide that we like some of them, that some of them are good and that others are bad or perhaps even evil, and we have evolved a certain degree of autonomy to choose our own motivations in life. And so I think of moral systems as human inventions, they're technologies of living together in the world.

0:58:00 DH: And just like all technologies, they have bugs, and that as the world changes, technologies become outdated. But I have a real respect for moral questions, but I think that they're not directly coming from our evolutionary past, that they're actually cultural inventions, constructs that we attempt to use to live together with each other.

0:58:25 SC: Well, you're preaching to the converted, as it were, because that's very compatible with the point of view I took in The Big Picture, so therefore I am empowered to play the devil's advocate and give you a hard time about it because I'm on your side already, but I think that if we could conjure up a skeptic, they would say, well, that picture you're saying maybe sounds a little circular, right, I mean, of course, we evolve, we're naturalistic beings, so we have desires, we have individual goals, there are things that we want, and what's different between what you said and just me saying that morality is a scheme I cook up to get as much of my desire satisfied as I want, that sounds very different than a classical moral realist would want things to be.

0:59:11 DH: A moral system has to be accepted by the society as a whole, so we cannot just impose our own particular selfish views on the rest of individuals. So that is the first thing I'd say. I think another theme of my book is that you might gather when you read the book, I'm not opposed to circular arguments, I think that... I shouldn't say a circle just comes back to the same point, but the whole principle of life is that it's recursive, and the analogy I use in the book a lot is chickens and eggs, eggs develop into chickens and then chickens lay eggs that develop into chickens, so life itself is circular or recursive, it constantly repeats. And it's that repetition from which meaning and purpose evolves, it's because of the recursive nature that a gene's effects have a causal role in whether that gene is perpetuated.

1:00:19 DH: So when you look at, say, the origin of morality and argue that the position I'm taking is a somewhat circular position, I would say, what's the problem with a recursive argument. I was greatly influenced actually by... It's not really acknowledged in the book, but by Douglas Hofstadter's Gödel, Escher and Bach that I read when I was an undergraduate, and it's all about the odd features of recursion and self-reference. And natural selection is a recursive self-referential process, and it has a lot of the very odd properties that Hofstadter wrote about in that book.

1:01:07 SC: A philosopher would just say that you're finding a reflective equilibrium between the urges you have, but I guess your point is that we also have higher cognitive capacities that can go beyond just fulfill our urges and create something more. So the worry is that it just becomes the naturalistic fallacy, that you say that what exists in nature already is good, that we should find our purpose from whatever we evolved to do and call that moral or natural or good. And I think the point of view that you're putting forward is a little bit more sophisticated than that.

1:01:42 DH: So I'm definitely... Definitely do not believe in the naturalistic fallacy, that I believe that it's part of all of the good things that we're capable and all of the evil, terrible things that we're capable of are part of our evolved nature. So that to behave morally, to just go back to our evolutionary past, I think that's fundamentally misunderstanding the choices that we have to make in our life here and now, that we have evolved to make choices in environments that have never occurred before. The world we're living in now is very, very different from the world in the past. We have that flexibility because organisms that were able to make their own decision rather than just rely on instinct were able to survive better than purely instinctual beings, and so we have acquired a freedom that can then look at our own motivations and choose some of them as preferable to others, so that, yes, no, I'm definitely not arguing for getting back to nature.

1:02:53 SC: And this importance of recursion is clear throughout the book, but you also do something a little mischievous with it, in that you relate it to French thinker, Jacques Derrida. Derrida is right there in the title of your book, From Darwin to Derrida, and I think that among many scientists, he is like just the symbol of sort of nonsensical obscurantism, and I'm not one of those scientists, but maybe I can give you the opportunity to explain why you thought that Derrida would be a good perspective to bring into this discussion of evolution and morality and meaning.

1:03:29 DH: Well, the original title... Well, one of the titles I had for the book was Degrees of Freedom, and for a variety of reasons that title was not available, and one of the themes of the book that I wanted to make was that natural selection is the process by which meaning and purpose come into a world without meaning and purpose. So meaning and purpose are traditionally the concerns of the humanities and the social sciences, so I wanted to talk to that community as well as to a biological community, and very late, actually, in the writing of the book, I started to think of genes as texts, and so I went to look at what the humanities had to say in texts. And I read some of Derrida's works on how meaning is continually being rewritten, that there is no original sense to a text, and I found that there were a lot of parallels to what I was thinking about in biological evolution, including my resistance to the idea of a thing's function is what was ever the original... What it had originally evolved to do, whereas I think that the functions and purposes of things are continually changing.

1:04:56 DH: And so that sense of change, I see parallels to Derrida. And once I decided to take the title, Derrida is opposed to the metaphysics of presence, of the idea that there is some sort of reality out there that exists independent of our interpretations of it. And so I thought of a conceit of calling the book Darwin to Derrida and never actually mentioning him throughout the whole book, but I decided that would be far too sophisticated a joke. So he is mentioned sparingly, but I think that there are parallels between the idea in literary theory that meanings are continually being reinterpreted at every writing and rewriting of the text, and that the functions and purposes of life are continually being reinterpreted as the genetic text is evolving because of its interaction with the environment.

1:06:03 DH: And I would say in evolutionary biology, natural selection is the process by which information from the environment is being encoded in the genetic material, and so the genetic material then comes to refer to that very, very complex environment. So it's... It's not that... It's a recursive process, so information in the genes is being expressed in the development of organism, but the information in the genes is coming from the complex interactions of those organisms with their environment.

1:06:44 SC: Yeah, and actually, I really, really like that and I like that explanation you just gave, it illuminates what I got out of reading the book very clearly. I'm torn a little bit because as a theoretical physicist, I have to be foundationalist in some sense, I think that there is a real world, the physical world, and probably you agree with that, but Derrida, he said a lot of things, but one constant theme was this anti-foundationalism. Of course, he wasn't thinking about physics, he was thinking about meaning and culture and literature and philosophy, and there I'm very sympathetic, and I think that you're right, that whether people are very religious or completely atheist, there's this strong desire to find absolutely unshakable foundations. And Descartes made it very clear, but it's still clear today in a lot of atheist thinkers and the idea that morality and meaning and purpose in life is not solved by a simple algorithm, but rather something that emerges from a complicated web of interconnected things going back and forth with each other makes people a little nervous, a little queasy, a little dizzy, and learning to accept that is hard.

1:07:54 DH: Yeah, no, I am a believer in a real world. All that we have are our perceptions and our perceptions are interpretations of the world, but we can trust our perceptions, especially when we're interacting with the non-living world, because our perceptions have evolved to be useful. Our perceptions are accurate because they're grounded in the need to know. The example I use is of a gazelle fleeing from a cheetah, it definitely needs to know what that cheetah is doing, how it is moving, because if it doesn't know it will be eaten. And so I do believe that our perceptions do give us objective information about the world.

1:08:54 DH: It's a little bit more complex in our interaction with other individuals, because other individuals may have motives to manipulate our own perceptions, to change our interpretations of the world, and we have motivations to manipulate them. And so when it comes to the world of interpersonal relations, I'm not sure that we can trust our perceptions of things, because we may have motives to deceive, including motives to deceive ourselves. So I'm quite a relativist in the realm of human interactions, but in terms of our perceptions of the physical world, with limitations, I think we can, though our perceptions are subjective, they have evolved to give us objectively useful information.

1:09:52 SC: Right, yeah. No, okay, I'm completely on board here, so maybe to wrap things up, since we have been on board, I can bring up to you a criticism that was made of my book, which I think is a halfway fair criticism that I talked a lot about meta-ethics and meta-meaning in some sense, like what it means to distinguish between right and wrong and where meaning might come from, but much less about how I would actually say what is right and wrong, what is the correct moral system, or what is the meaning of life, that kind of thing. From your evolutionary perspective, do you think that there is useful information or insight you can give to people about not just the origins of morality and meaning, but what the actual morals and meaning should be that we choose to live by?

1:10:43 DH: So the way I put it in the book is that the meaning of the life is the life that is lived, that our lives are an interpretation of the information we get from our environments and I... And the meaning in my conception of meaning is that interpretation, we are judged by the choices that we make, each... There is a meaning of each individual life, and that's one that we in some sense create for ourselves. I wouldn't say that there's an overarching meaning of life considered as an abstract, abstract entity. And so that's why I deliberately use the plural in the title. It's about the meanings of life. There is a meaning to the life of each individual slug, there is a meaning to the life of each individual human being, and in some sense that meaning is defined by the choices, the interpretations of that organism.

1:11:46 SC: Yeah, I did a podcast, a solo podcast for my 100th anniversary, my 100th podcast episode where I talked about the meaning of life in a little bit more substantive way than I did in The Big Picture. And I said that, like you, there's not one final meaning, but there can be individual meanings that different people come up with, and actually, this is something that I haven't yet mentioned in the podcast but I wanted to ask you about, which is the fact that in biology, in genomics or in human life, the space of possibility is unimaginable large. The number of possible DNA sequences or the number of possible choices you can make to live your life, and evolution is of one algorithm or procedure for kind of searching through there, and we can talk about how efficient it is, but... So I brought up the idea that we can think about meaningfulness in life from diverging from the easiest possible path in all those choices that we make, there are things we can do that we put value on that are harder than just going with the flow, and that's where meaningfulness comes from. Is that something you'd be sympathetic to?

1:12:52 DH: Yes, I think just repeating what's done in the past... Well, the metaphor I used at one place in the book is of playing a card of hands, that the cards are ancient, the particular genes that we are dealt, but each individual life is unique, it's a unique combination, and it's what we do with that card of hands that we're dealt that is important. And some people are going to be given a very, very poor card of hands and others get a very good hand that it's hard to lose with, but we are judged by what we do with the cards that we are dealt.

1:13:42 SC: Right. I think that's a very good way of putting it and a perfect place to wrap up, so David Haig, thanks so much for being on the Mindscape podcast.

1:13:48 DH: Thank you, Sean.

[music][/accordion-item][/accordion]

Great stuff. Higher-level phenomena aren’t just statistical regularities or convenient descriptions, they are a real part of the universe and have actual causal power.

To make the nuclear bomb that exploded on Hiroshima trillions of atoms of plutonium had to be precisely organized to undergo reaction. This organization came about as a result of human intentions. But suppose you were a Laplacian demon who didn’t know about any higher-level phenomena like intentions and just traced over all the atoms on the earth going about their interactions. What you would see is that at some point in the Earth’s history trillions of plutonium atoms just happen to come together and undergo an enormous explosion. But this wasn’t *really* the cause of the explosion. It was caused by the higher-level phenomena of human thought and intention “reaching down” to the lower physical level of atoms and organizing them into a bomb.

It’s strange how these two different levels of causation can co-exist. It’s often just glossed over and I don’t think it’s fully understood.

General note: more often than not recently, concepts such as “free-will”, “meanings” etc that have taken a serious blow from modern scientific advances (at least as far as naturalists are concerned), are re-surfacing under some notion of emergentism. It seems as if the very modern and interesting (and not yet fully understood?) field of complex systems, is invoked to support some sort of dualism (see property dualism, emergent materialism etc) as deus ex machina (ie without actual supporting scientific evidence).

Pingback: Sean Carroll's Mindscape Podcast: David Haig on the Evolution of Meaning from Darwin to Derrida | 3 Quarks Daily

Very appropriate to hear David’s Australian voice after binge watching all ten episodes of Netflix “The Crown” this past weekend. The story centers on all of the individuals in the family seeking their meaning. Last dialog scene is Prince Phillip explaining who they all really are.

Pingback: David Haig on the Evolution of Meaning from Darwin to Derrida - The Social Science Collective

Sean, your podcasts always fascinate. Occasionally though, one can really have impact for me. This is one.

Thank you.

Wonderful. Also triggering for me. Bear With me.

The need, the drive of these scientists certain ground, for definitive stance. These areas of research, including Haig, and also Dennet, Dawkins, Shannon, invoking semantics, linguistics, information theory, Darwin. Nothing at all with any of these arguments. Which comes first? the scientist or the human?

If any of these scientists were to experience an addiction or a diagnosable DSM-V mental illness, how would a skilled psychotherapist help them? Behavioral, Reductive, REBT, Evidence based. All of these favored psychologies take a back seat to psychotherapy, which holds a larger view, a broader conception of what constitutes a human being. To have a set number of sessions with predictable outcomes trumps subtle, thorough interpretations of healing human beings.

It seems Haig and his invoked titans spend enormous energy avoiding any psychological stance.

What I’m struggling to get at, I think: these folks, and most contemporary academics, try to negate psychology, to negate dependency of others, of community, of a therapy or a spiritual guide.

If one of them comes into my office tomorrow, I will know how to help them– usually. It has little or nothing to do with the scientific searching and stance they promote.

Schizoid behavior (see the DSM definition of Schizoid personality disorder) can be seen on a continuum. Look it up, and see how independence drives these bootstrapped personalizes.

I actually love the subject, the broadness, the TOE attempt is breathtaking and fun. But there is still a huge hole in all touched upon by these.

It seems to me that this fascinating dialogue, while intriguing, is not completely satisfying because it does not address the hard problem of consciousness. Introspective consciousness and self awareness are necessary to ascertain meaning. Without it, the entire universe would have no meaning, and might as well not exist. All of the parallel universes, and the many world universes might as well not exist. Anything that is not perceived, has no tangible meaning. A computer’s output has no meaning to the computer. The output only has meaning in the mind of its user. Until more is known about the mystery of human consciousness, we should understand that everything else is speculation. Consciousness is fundamental.

I’d like to thank David Haig for introducing me to the word “teleophobia”. It’s a word I’ve needed from time to time. It seems to have been coined by Karl Ernst von Baer to talk about Darwin.