One of a series of quick posts on the six sections of my book The Big Picture — Cosmos, Understanding, Essence, Complexity, Thinking, Caring.

Chapters in Part Five, Thinking:

- 37. Crawling Into Consciousness

- 38. The Babbling Brain

- 39. What Thinks?

- 40. The Hard Problem

- 41. Zombies and Stories

- 42. Are Photons Conscious?

- 43. What Acts on What?

- 44. Freedom to Choose

Even many people who willingly describe themselves as naturalists — who agree that there is only the natural world, obeying laws of physics — are brought up short by the nature of consciousness, or the mind-body problem. David Chalmers famously distinguished between the “Easy Problems” of consciousness, which include functional and operational questions like “How does seeing an object relate to our mental image of that object?”, and the “Hard Problem.” The Hard Problem is the nature of qualia, the subjective experiences associated with conscious events. “Seeing red” is part of the Easy Problem, “experiencing the redness of red” is part of the Hard Problem. No matter how well we might someday understand the connectivity of neurons or the laws of physics governing the particles and forces of which our brains are made, how can collections of such cells or particles ever be said to have an experience of “what it is like” to feel something?

These questions have been debated to death, and I don’t have anything especially novel to contribute to discussions of how the brain works. What I can do is suggest that (1) the emergence of concepts like “thinking” and “experiencing” and “consciousness” as useful ways of talking about macroscopic collections of matter should be no more surprising than the emergence of concepts like “temperature” and “pressure”; and (2) our understanding of those underlying laws of physics is so incredibly solid and well-established that there should be an enormous presumption against modifying them in some important way just to account for a phenomenon (consciousness) which is admittedly one of the most subtle and complex things we’ve ever encountered in the world.

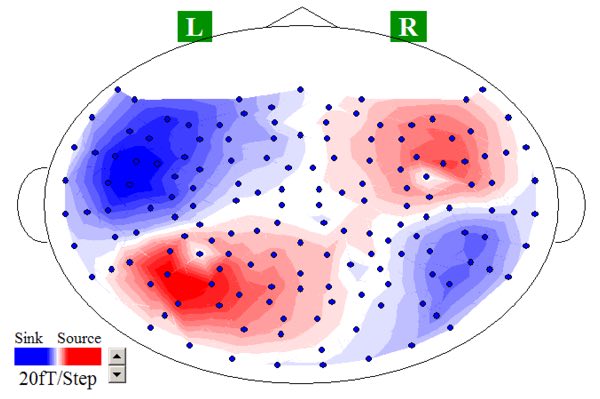

My suspicion is that the Hard Problem won’t be “solved,” it will just gradually fade away as we understand more and more about how the brain actually does work. I love this image of the magnetic fields generated in my brain as neurons squirt out charged particles, evidence of thoughts careening around my gray matter. (Taken by an MEG machine in David Poeppel’s lab at NYU.) It’s not evidence of anything surprising — not even the most devoted mind-body dualist is reluctant to admit that things happen in the brain while you are thinking — but it’s a vivid illustration of how closely our mental processes are associated with the particles and forces of elementary physics.

The divide between those who doubt that physical concepts can account for subjective experience and those who are think it can is difficult to bridge precisely because of the word “subjective” — there are no external, measurable quantities we can point to that might help resolve the issue. In the book I highlight this gap by imagining a dialogue between someone who believes in the existence of distinct mental properties (M) and a poetic naturalist (P) who thinks that such properties are a way of talking about physical reality:

M: I grant you that, when I am feeling some particular sensation, it is inevitably accompanied by some particular thing happening in my brain — a “neural correlate of consciousness.” What I deny is that one of my subjective experiences simply is such an occurrence in my brain. There’s more to it than that. I also have a feeling of what it is like to have that experience.

P: What I’m suggesting is that the statement “I have a feeling…” is simply a way of talking about those signals appearing in your brain. There is one way of talking that speaks a vocabulary of neurons and synapses and so forth, and another way that speaks of people and their experiences. And there is a map between these ways: when the neurons do a certain thing, the person feels a certain way. And that’s all there is.

M: Except that it’s manifestly not all there is! Because if it were, I wouldn’t have any conscious experiences at all. Atoms don’t have experiences. You can give a functional explanation of what’s going on, which will correctly account for how I actually behave, but such an explanation will always leave out the subjective aspect.

P: Why? I’m not “leaving out” the subjective aspect, I’m suggesting that all of this talk of our inner experiences is a very useful way of bundling up the collective behavior of a complex collection of atoms. Individual atoms don’t have experiences, but macroscopic agglomerations of them might very well, without invoking any additional ingredients.

M: No they won’t. No matter how many non-feeling atoms you pile together, they will never start having experiences.

P: Yes they will.

M: No they won’t.

P: Yes they will.

I imagine that close analogues of this conversation have happened countless times, and are likely to continue for a while into the future.

I think a lot of the “hard problem” comes down to overthinking things.

Though there seem to be some philosophers who see a distinction between “consciousness” and “self-awareness,” everybody agrees that the two are, if not identical, then very closely intertwined.

Self-awareness means, literally, that the self is aware of the self. This is a very direct and straightforward form of recursion, akin to a pair of mirrors placed parallel to each other or a video camera pointed at a live monitor.

We already know that the brain has “mirror neuron” structures that create virtual models of the brain states of those around us as we observe them. It is very simple to propose that those structures are what constitute awareness of the emotions of others. At a much simpler level, we also know that the visual cortex encodes (in a manner that can be decoded via sophisticated scanning and computer analysis) the images that our eyes project on our retinas — and it is equally simple to propose that that’s our awareness of our visual field.

All that it takes for the self to be aware of the self is for some of those mirror neurons to be mirroring not people around us but rather our own internal mental states. And meta-cognition is therefore nothing more than the mirrored self recursively mirroring itself.

Objections to this get all hung up on the “feels like” matter. But, the thing is, for there to be awareness of any sort, it must “feel like” something. what that feeling actually is is largely irrelevant, much as eye color is largely irrelevant to the ability to see. We just happen to “feel like” what we “feel like,” but, if there’s no “feel like” at all, then there’s no awareness. There might be some interesting things to discover about the forms our “feelings like” take, same as there’re interesting things to discover about human eye color (genetics, chromatin, evolution, more). But we should no more be surprised that an organism that has self-awareness has a “feel like” than we are that an organism that can perceive the visible electromagnetic spectrum has eyes.

Cheers,

b&

There’s a fresh way of examining the mind-body problem that would allow the issue to be resolved empirically.

Instead of abstract arguments, my suggestion is that we look at what happens in concrete terms when we try to predict what other agents what might do next. What actually happens on a concrete level when we try to construct a model of other agents?

A model of something is equivalent a computer program, or simulation of it. So what actually happens when we try to write a computer program to simulate the behaviour of say a human being?

I put it to you, that *in practice*, we simply would never be able to simulate another human being on a purely physics level. It’s just too complicated. In order to *actually* (in practice) predict the behaviour of another human being, we would unavoidably have to reference high-level mental properties. That is to say, in our computer program, we would have to unavoidably include particular classes in our program that refer to mental characteristics that the agent in question possesses if we actually want to make useful predictions.

Now, you might try to argue that these high-level concepts are just a useful way of talking about the agent, that all that exists in reality is physics and the mental properties referred to in our simulation are just a part of the model, not reality.

But Stephen Wolfram has discovered that computer programs that exceed a certain level of complexity are *irreducible* EVEN IN PRINCIPLE. That it is say, the only way to predict what these types of programs will do is actually to run them. There is simply no computational short-cut that would enable you to predict the behaviour of the program if you only refer to physical operations.

I put it to you, that if the programs that model human beings are of this type, then there is no way to strip out references to mental properties from our explanation of what the programs do, EVEN IN PRINCIPLE if we want to make useful predictions. In other words, our references to mental properties would not just be a useful fiction, they would actually be INDISPENSIBLE to our explanations of reality!

I put it to you, that if references to mental properties are indispensable to our explanations of agent behaviour, in the concrete sense that we cannot predict the behaviour of a computer program that simulates an agent without actually running the program, unless we reference mental properties, then we must in fact conclude that these mental properties actually do exist in reality, not just in our model, and that reductionism has failed!

zarzuelazen:

Though true, it’s irrelevant.

When you put together Sean’s observation that human-scale physics are completely known with the fact that those physics are perfectly computable, all you have to do is create a physics simulation to whatever degree of accuracy is necessary to simulate a brain. In practice, you wouldn’t need to go beyond the cellular scale in your simulation…but, even if you want to invoke some sort of mysterious indeterminate quantum woo in your explanation, that just means that you have to expand your simulation to that level.

Yes, we’re a loooooong way from having computer hardware with the computational oomph to do that sort of thing. But we’re also a loooooong way from having computer hardware that can fully model stellar dynamics — and yet that limitation doesn’t cause us to think that maybe the real, ultimate source of sunlight is something mysterious that can’t even in principle be modeled. Let alone that, maybe, the old model of light emanating from eyes and propagating via ether is right after all.

Cheers,

b&

Ben Goron,

Perhaps you misunderstood my points? I entirely agree that consciousness is computational and that it can indeed be modelled. What I was discussing was reductionism and the question of whether or not non-physical (mental) properties exist.

I was using Wolfram’s principle of computational irreducibility to suggest that you can’t have a model of a person without actually *creating* a person! In other words, it’s possible that there is no computational short-cut you can use to create an unconscious model of a person. Any model of a person must *necessarily* become conscious (and hence the model would actually *be* a person!)

I then pointed out that this actually implies a failure of reductionism , because if we can’t predict what our program of a person’s mind will do without actually running the program or referencing mental concepts, then we must concede that these mental concepts have an external reality over-and-above the merely physical.

I am using David Deutsch’s criterion for reality here: *if* given concepts become indispensable to our explanations of reality, *then* we have to say that these concepts actually exist in reality, not just in our models.

So the argument runs as follows:

IF you can’t predict the behaviour of the program of a person’s mind without actually running the program (which would actually create a conscious person!) or making references to mental concepts in your explanation of what the program does

THEN the mental concepts have become indispensable to your explanation of reality, because you were unable to strip out these concepts from your models.

It logically follows that these mental concepts must be referring to something that actually exist in reality. The conclusion is that reductionism has failed and non-physical mental properties do exist.

zarzuelaezen, I’m afraid your approach isn’t all that useful. It applies equally well to radioactive decay and long-term multi-body orbital dynamics — or, for that matter, billiards.

Either we must apply your criteria equally and conclude that reductionism has failed and non-physical billiard ball properties do exist, or we must reject your analysis.

I’m going with the latter — and I rather suspect our host would, too.

Cheers,

b&

Hi Ben,

No, the examples you give are totally different from my example. For instance in the case of billiard balls, I agree that the high-level properties of the billiard ball indeed do not exist in reality.

You can see that concepts like ‘balls’, ’round’ etc. are indeed just ‘useful fictions’, because these concepts are not indispensable to your model of billiard ball behaviour – you could in fact write a computer program where you have totally stripped the concept of a ‘ball’ out from your model and still make useful predictions about the behaviour of what you see in terms of low-level physics only.

So reductionism works perfectly for billiard balls 😉

The case of mental properties is very different, because to make useful predictions about conscious agents, you would be unable to strip out the references to mental properties from your computer program modelling those agents. There is no low-level physics model that can predict what the agent would do. You *can* still model the agent, but only by referencing high-level mental concepts (and remember, if you simply run the program to see what it does, this will unavoidably create a conscious person – again, you have failed to escape the references to mental concepts). Reductionism has failed!

M seems to be making the fallacy of division. It’s the fallacy that says the properties of the whole must also be contained in the individual parts. The brain as a whole is conscious, but the individual atoms do not have to be.

I come across this very often when discussing consciousness with people.

Interesting discussion above. I do wonder if the P vs M discussion will be decided, to most folks satisfaction, when sufficiently good simulation of neural function is achieved, and people just get used to the idea.

I’m pretty sure I’ve seen Sean use the example, “Is baseball real?,” in a similar discussion about time. Baseball and time are both definitely real, but the former is not fundamental (the jury is still out for time). And there is no danger that physicists will ever make sports commentators obsolete.

Materialists and Dualists have their understandings of the Hard problem. I would look toward philosophy to help out in this discussion, as how can matter (approx 3lbs) have the ability to think(belief, desire etc…), feel (pains/tickles etc…), be aware of objects, states of affairs etc…

John Searle (UC Berkeley) is such a person that has been philosophizing about this issue for years. If you don’t know the difference between – observer independent and observer relative, this issue will continue to befuddle those that talk about computational-ism as a natural process as human consciousness? Learn

Your claim is trivially empirically demonstrated false. You yourself are able to make useful predictions about conscious agents without computer modeling, and the fields of marketing and political science (and many others) are hugely successful with their reliance upon computer modeling.

The models aren’t perfect, of course — but, then again, neither are the models of billiards tables.

b&

The “how” is, of course, gong to be a most fascinating problem to tackle…but we already know that it must be the case. A claim to the contrary is exactly equivalent to one that the LHC failed to observe an otherwise-unaccounted-for particle with a mass less than that of the Higgs.

Cheers,

b&

“My suspicion is that the Hard Problem won’t be “solved,” it will just gradually fade away”.

Indeed. Chalmers is a philosopher, and has invented a category (‘qualia’) without any testable consequence. When you put in opsins that rats don’t code for into their retina, they can very well see “green” without having any previous experience of it. The body-brain is plastic, Chalmers is not.

@zarzuelazen:

I’m part way with Ben here.

“Wolfram’s principle of computational irreducibility … a failure of reductionism … David Deutsch’s criterion for reality … we must concede that these mental concepts have an external reality over-and-above the merely physical”.

More lack of plasticity, for much the same reason. Wolfram is a computer scientist dabbling in philosophy, “reductionism” is a failed philosophic description of a useful science tool, Deutsch is a philosopher dabbling in science, and ‘mental concepts’ has no testable definition.

That we can describe dynamical systems in forms (algorithms or programs, if you will) that have no solutions or can’t be predicted long term is irrelevant to biochemical systems. They have evolved to be robust.

If you must back down to the magic-of-the-gaps of defining reality in a testable way, that – evolution resulting in robust system properties – maps well. A real characteristic is robust under observation so it can be predicted and tested. Deutsch is failing to produce a scientific, testable definition of system properties.

In other words, you are trying to claim that since we can’t know the form of every snowflake, we can’t predict avalanches without making our own snow falls. and our knowledge of water ice is no help. But we can, and it is.

Equivalently you are saying that our inability to predict weather long term means there is no climate, and that we can’t model climate without making our own weather and our knowledge of atmosphere is no help. But we can, and it is.

TL;DR: There are no ‘mental concepts’, they definitely wouldn’t be magically ‘unreal’ if they existed, and we don’t need to ‘simulate’ the brain-body system of an organism in order to understand its workings, whether emergent or not.

I have no idea what you mean with that investigating systems in detail has “failed”, but I note that there is a result doing the rounds that such an investigation has rejected the ‘mental concept’ (if I understand your notion) of ‘free will’. Seems social organisms like us evolve the confabulation of ‘making choices’ so that we can control our groups by ‘punishing bad choices’. That confabulation overwrites our memories of brain-body states as necessary, we fool ourselves.

So did I just test ‘free will’? No, I tested the notion of ‘mental concepts’ as meaningless.

“How could giving human consciousness to a machine require blinding that machine to itself?”

“Believe it or not, there was a time when I could have told you almost everything there was to know about this screen. It was all there: online information pertaining to structure and function. My experience of experiencing was every bit as rich and as accurate as my experience of the world. Imagine, Elijah, being able to reflect and to tell me everything that’s going on in your brain this very moment! What neuron was firing where for what purpose. That’s what it was like for me…”

https://rsbakker.wordpress.com/2016/03/22/the-dime-spared/ (hopefully I won’t trigger some spam filter)

This is a story to explain one possible solution to the hard problem.

I think the thesis is convincing and fairly intuitive once the fundamental leap is made: the qualia, aka consciousness as it appears, acquires its shape and quality because of informatic occlusion. Or: the fact the brain can’t efficiently observe itself creates the conditions for consciousness as it appears and feels to us.

I think Dennett explained a similar idea through the concept of the crane/skyhook: if we cannot observe the arm of the crane, and so observe how the skyhook movements depend on the movement of the arm itself, the picture we obtain (qualia) is that of this skyhook flying autonomously. As if following its own independent “will”.

So, because the brain has a built-in systemic anosognosia (the absence of perception of something missing, producing a feeling of sufficiency), we perceive consciousness as cohesive and sufficient thing, as if it is separate from the material brain. An autonomous skyhook.

We have consciousness, and qualia, because we are structurally blind. That blindness itself is what produces and gives the specific form of the hard problem. The separation between mind and body.

Sean the poetic naturalist (P) sez:

” What I’m suggesting is that the statement ‘I have a feeling…’ is simply a way of talking about those signals appearing in your brain. There is one way of talking that speaks a vocabulary of neurons and synapses and so forth, and another way that speaks of people and their experiences. And there is a map between these ways: when the neurons do a certain thing, the person feels a certain way. And that’s all there is.”

The statement “I have a feeling” is about a feeling, which may or may not be identical to signals in the brain. That identity claim hasn’t (yet) been established in the philo-scientific community, mainly because feelings aren’t observable but brain states are, and feelings are qualitative, brain states aren’t. The close association between the two domains is well-established, but again that doesn’t establish a numerical identity according to Leibniz’ law: identicals have all properties in common. And it’s crucial to see that experiences aren’t ways of talking, but true existents in their own right, about which we talk. The poetic naturalist seems sometimes disposed to put talk before, or as dispositive of, ontology.

P continues:

“Individual atoms don’t have experiences, but macroscopic agglomerations of them might very well, without invoking any additional ingredients.”

This nicely adverts to the private, subjective status of consciousness: it only exists for the agglomeration, not for outside observers that can see the agglomeration and its structure. The naturalization of consciousness has to account for the existential privacy of experience, as contrasted with the existential publicity (intersubjectivity) of the physical states of affairs that support it. And it has to account for qualia – the qualitative aspect of experience. Since physical states of affairs are neither subjective nor qualitative, this suggests science might look to a higher-level theory – e.g., information theory, representationalism – to explain and encompass consciousness as a natural phenomenon that isn’t available to observation in the way that physical objects are.

Torbjörn,

If mental concepts were meaningless, you’d have to rip out half the pages of your dictionary 😉 In your daily life, you are certainly not using your knowledge of physics to understand the people you interact with – you are using mental concepts all the time…you think… that person is ‘happy’, this person is ‘sad’ , that guy is ‘bad’, this guy is ‘good’ etc. etc. So mental concepts are both meaningful and highly useful, in fact, you couldn’t function in society without them.

Stephen Hawking himself has talked about the mind-body problem, and he agrees that the practical criterion of whether or not you could in practice predict an agent’s behaviour in mechanistic terms is actually a good operational test of free-will.

Ben,

Go back and read what I actually said. I clearly stated that you CAN model agent behaviour….but you don’t use your knowledge of particle physics to do that 😉 To understand people, you are using mental concepts (see previous paragraph above). And the fact that these mental concepts are so useful is precisely evidence that there really do exist non-physical things in reality.

There’s an analogous case here with mathematics. In mathematics you also have a case where there are highly abstract concepts being talked about and it’s not clear how they could fit into the physical world. And you have an analogous debate where there are people on one side saying that mathematics is just a language we use to describe reality (nominalism) and people on the other side saying that mathematical objects such as ‘numbers’ really exist out there in reality (platonists).

But the fact that mathematical concepts are so highly useful in our explanations of reality is again, strong evidence that there really do exist non-physical mathematical entities out there in reality.

What really puzzles me about consciousness is this:

Why am I now consciously aware of being in my body seeing through my eyes, but not in another body seeing through other eyes?

(Any functioning human body is apparently the physical embodiment of a consciousness, and yet I am only consciously aware of the particular human body I inhabit. Why? Why do I inhabit this body and not another one? What is I who is inhabiting a body?)

Haruki Chou,

information. You only access information that is part of you. Same as you can see only what you can see through your own eyes and not what someone else sees.

The confines of information are the confines of a single brain. Then consciousness is a small subset of that brain. Just what information is left after heuristic toss away the great majority of it.

Don’t fail to read The World-Thinker (Jack Vance).

Some observations, not necessarily agreeing or disagreeing with anyone else.

Modelling or simulating the brain/consciousness isn’t the same as creating it just as a model or simulation of water in a glass isn’t wet or able to be drunk.

Brains and consciousness do not exist in isolation from bodies. To be conscious means to be embodied.

Consciousness is completely dependent on a relatively small number of cells in the brainstem in an area formerly known as the reticular activating system. Damage in this area alone even with intact cortex and brain elsewhere will produce a coma. So theories like Integrated Information Theory that suggest consciousness is the product of networked neurons need to explain why it is so dependent on such a small number of cells.

Most of what the brain does is unconscious. For my part, I cannot see a compelling evolutionary explanation of why anything needs to be brought into consciousness. However, the reticular activating system mentioned above is in evolutionary terms very old and goes back millions of years to the earliest vertebrates where it serves to monitor and maintain inner body state and to integrate external stimuli. So consciousness probably is deeply involved with those tasks.

One last thing I would like to bring to the discussion is the ideas of Donald Hoffman. I wrote about them here and there was an interview in Quanta Magazine that I link to.

https://broadspeculations.com/2016/04/26/world-stuff/

Even if you don’t want to go all the way to conscious realism, his multimodal user interface theory is interesting.

Rather than trying to ‘solve’ the mind-body problem, let’s assume Sean’s ideas are right. So, then, we are only atoms and thus free-roaming (disconnected) fairly clever robots. How do robots come up with sayings like “Before enlightenment, chop wood and carrry water…after enlightenment chop wood and carry water”? Even if enlightenment was a false concept how would a robot imagine it?

zarzuelazen:

But then we’re right back where we were. When you play billiards, you most emphatically don’t use your knowledge of particle physics to do so.

In short, you’re claiming that the phenomenon of cognition is fundamentally different from all other phenomena, yet all your attempts at supportive examples demonstrate the opposite.

Cheers,

b&

Haruki Chou:

This is exactly what one would expect should it be the case that consciousness is a phenomenon or property of the brain. Your brain is only connected to your body, not to other bodies, so it should be quite remarkable if your brain saw through eyes not connected to it.

Indeed, your question is a very simple way of demonstrating that the naturalist answer is far more coherent than the supernaturalist one. If consciousness is distinct from the body, what is it that binds consciousness to the body? Worse, how does an immaterial consciousness compel the physical body to do work (as physicists define the term) without violating conservation?

Cheers,

b&

Steve Mudge:

Why shouldn’t any sufficiently sophisticated arrangement of matter be capable of whatever feats you might care to propose?

Creationists have a great trouble getting past the mental hurdle of comprehending “deep time.” Our entire lives span a mere century at most, if we’re lucky, and few of us see more than a couple generations of our own descendants. Even mentally encompassing the mere several millennia they propose for the age of the Earth is difficult if not impossible for most of us. Yet life on Earth is a few billion years old, and some unknown trillions or more of generations have passed in that span. And, as it turns out, that sort of time is more than enough for descent with modification and differential reproductive success to produce the diversity of life we see around us.

Similarly, most of us struggle even replicating the computational abilities of a pocket calculator, and modern smartphones are far beyond any human’s ability to fully comprehend in complete detail. Yes, we can make them do what we want by breaking it into pieces and aggregating and abstracting it and the like…but nobody can come close to comprehending the complete workings of the circuitry at the scale of logic gates.

And yet human brains are as much more complicated than smartphones as smartphones are more complicated than pocket calculators.

So why should it be surprising that human brains are as much more sophisticated and marvelous than smartphones as smartphones are more sophisticated and marvelous than pocket calculators?

Also, considering how hard it is for us to understand the inner workings of smartphones other than by appealing to high-level analysis that assumes the fundamentals…shouldn’t we expect to have to resort to the same sorts of techniques to even hope to understand human brains, and expect the task to be even more challenging?

Yet, it’s plenty clear that pocket calculators and smartphones are, at their base, nothing more than binary logic circuits behaving in simple well-defined ways…and we can also have overwhelming confidence that our brains and minds are the same general class of phenomenon.

Cheers,

b&

Ben: Very insightful but calculators also have tactile pads and LED displays to interface with the outside world. You’re inference is right that if the philosopher or even physicist had no knowledge of electronics and electronics manufacturing; the amount and type of dead ends which philosophers of mind wind up in their self perpetuating corn maze is similar.

vicp, calculators and computers certainly have interfaces to the outside world — but, then again, so do humans. Even better, we also have access to our own internal states, even if that access is woefully limited and frequently subject to distortion.

To continue the analogy…if confronted with electronics of unknown origin and design, an electrical engineer could bring an array of analytical tools and techniques to bear to reverse engineer its function. There are microscopes and oscilloscopes and x-ray imaging systems and all sorts of nifty things they have sitting on the shelf. And, while it’s true that they might not be able to recover the original design plans or specifications and maybe not divine the full details of the manufacturing process, it’s certainly conceivable that they could otherwise come to a complete understanding how how it actually does function.

Not coincidentally, we’re developing a similar array of analytical technology in the effort to understand minds. The brute physiology of the brain is already pretty well understood, as is the cellular function of neurons. We’re now focussing attention on more and more sophisticated real-time analysis techniques, especially including fMRI.

Our tools are still crude compared to the brains themselves, but we’ve already come a very long way.

Cheers,

b&